Tara A. Karasewich

Accessibility in Higher Education

Tara A. Karasewich

Department of Psychology

Queen’s University

Introduction

The most recent Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD) estimates a disability rate of 27% among Canadians 15 years and older (i.e., 8.0 million people), with disability defined as a long-term condition that limits daily activities (Statistics Canada, 2022). Past Statistics Canada surveys have found disability to be associated with lower education achievement (e.g., Berrigan et al., 2023; Canadian Human Rights Commission, 2017), and this is true of the 2022 CSD as well. For example, among the 25-to-44-year age group, disabled[1] Canadians were more likely than non-disabled Canadians to have a high school diploma (23.6% vs. 19.4%) or college degree (23.3% vs. 19.8%) as their highest level of education, while they were less likely to have completed a university degree (33.2% to 44.5%). There are many benefits to higher education – including an increased likelihood of being employed, higher salaries, and a positive association with healthy lifestyles (e.g., Ma et al., 2016; Morris et al., 2018) – so it is essential that post-secondary programs be accessible to all.

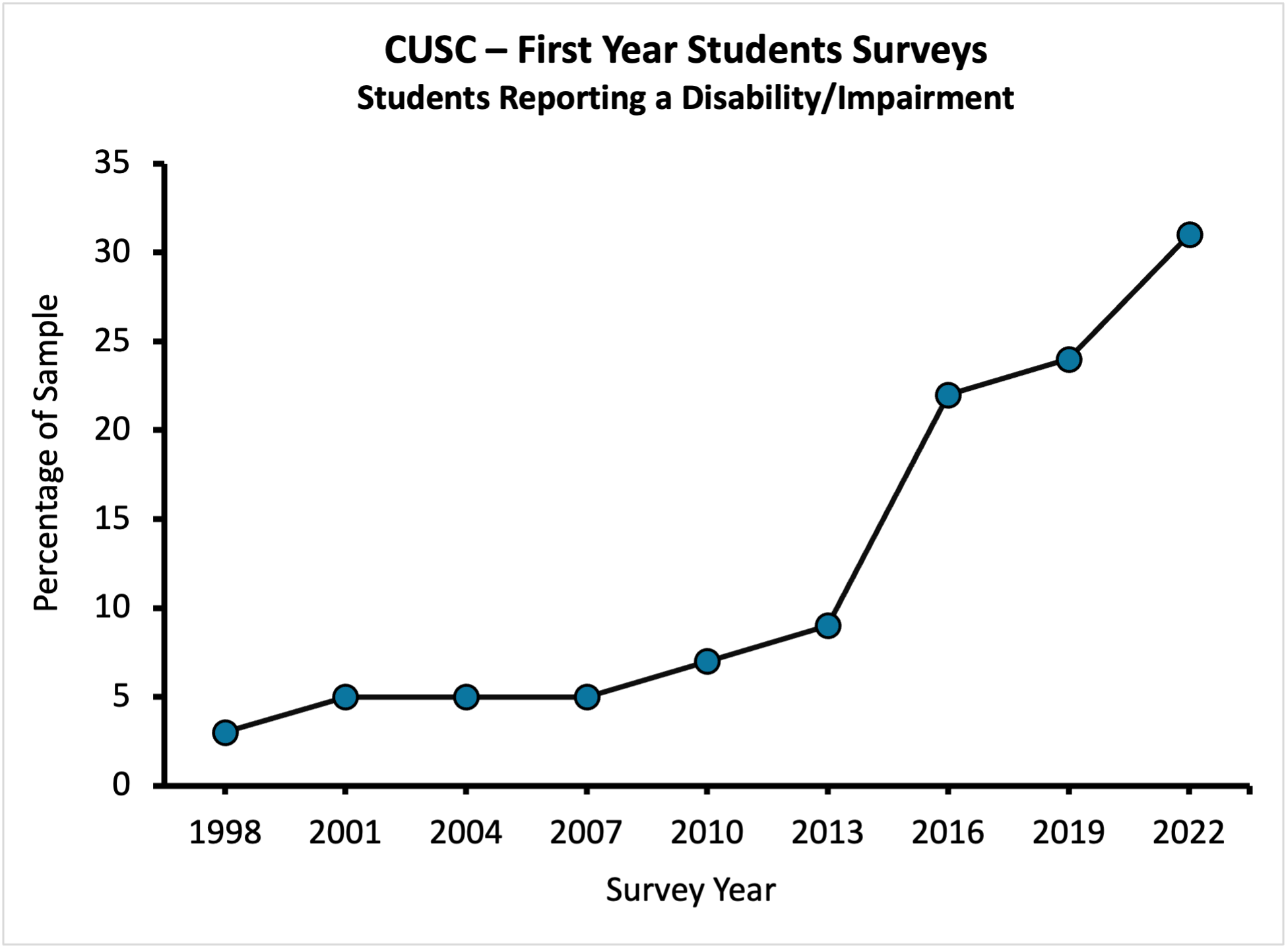

The Canadian University Survey Consortium (CUSC), who have been collecting data on students’ experiences at universities across Canada for thirty years, has observed a sharp increase in the enrollment of disabled students over the last decade (CUSC, n.d.). Figure 1 below plots data from all CUSC surveys that have examined first-year undergraduate students, and shows two distinct ‘jumps’ in the number of students who self-report having one or more disability: in 2016, when the rate rose from 9 to 22%, and in 2022, when it rose from 24 to 31%. Similar increases in disability rates have been observed in colleges across Canada as well (Deloitte, 2017). Mental health-related disabilities have shown the greatest rate of increase not only among higher education students but in the young adult population of Canada more broadly, which could be a sign of problems within the mental health supports available for youth (Moroz et al., 2020; Statistics Canada, 2023). However, these trends may also be the result of positive changes, such as: increased understanding of disability symptoms and earlier diagnoses, greater support to disabled students in secondary education, and decreased stigma (Deloitte, 2017; Stewart & Schwartz, 2018). In any case, it has become increasingly important to ask how post-secondary institutions can ensure they are meeting the accessibility needs of disabled students.

Figure 1

Note. Sample size varied by survey year: 5,548 in 1998, 7,093 in 2001, 11,132 in 2004, 12,648 in 2007, 12,488 in 2010, 15,218 in 2013, 14,886 in 2016, 18,092 in 2019, 15,157 in 2022. The full list of disabilities respondents could select is available for half of the survey years (i.e., 2001, 2004, 2016, 2019, and 2022). Although there was some variation, these surveys all included the categories of mental health, learning, mobility, hearing, speech, other physical disabilities, and an option to specify another type.

In this chapter, I examine the state of accessibility in higher education. First, I outline the rights of disabled students in Canada and how the legal duty to accommodate applies to the post-secondary environment. I then discuss two broad approaches that educators in colleges and universities can take to be inclusive of disabled students. At the individual level, instructors may grant accommodations to disabled students, as recommended by their institution’s disability services. At the course level, instructors may use principles of universal design to increase the accessibility of their class materials, activities, and assessments. Although I present these approaches separately, they are not mutually exclusive; instructors and institutions must still address individual need even when implementing universal design. I end this chapter by calling for accessibility to go beyond the classroom: to remove barriers to entry, ensure disabled students can participate in all aspects of post-secondary life, and better support them in entering the workforce.

The right to pursue higher education

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) guarantees every individual equal protection and benefit of the law without being discriminated against for having a mental or physical disability. A recent federal law, the Accessible Canada Act, provides further protections for disabled Canadians in multiple areas – including employment, communication, and transportation – with the goal of “creat[ing] a Canada without barriers by 2040” (Canadian Human Rights Commission, 2023). Unlike its counterpart in the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990), which explicitly requires postsecondary education to be offered in an accessible manner, the Accessible Canada Act does not apply to most colleges or universities. Instead, the rights of disabled Canadian students are protected through a mix of legislations that have been passed in response to human rights complaints, guidelines created by some provinces, and the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Jacobs, 2023).

Four Canadian provinces have accessibility legislation which explicitly states that disabled persons have a legal, human right to pursue post-secondary education, through the: Newfoundland and Labrador Accessibility Act (2021), Nova Scotia Accessibility Act (2017), Québec Act to Secure Handicapped Persons in the Exercise of Their Rights (2004), and Saskatchewan Human Rights Code (2018). The Accessible British Columbia Act (2021), which is in development, has also identified education as one of the areas for which it will provide accessibility standards.

Three other provinces have developed comprehensive accessibility guidelines for post-secondary education, through their Human Rights Commissions: Alberta (2021), New Brunswick (2017), and Ontario (2004). All three guidelines note that institutions have a duty to accommodate disabled students, up to the point of undue hardship. The Ontario guidelines describe appropriate accommodation as what “most respects the dignity of the student with a disability, meets individual needs, best promotes inclusion and full participation, and maximizes confidentiality” (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2004, p. 26). Appropriate accommodations remove barriers to disabled students without compromising academic standards. Thus, the Alberta guidelines note that disabled students have the same “responsibility to develop the essential skills and competencies of all students” (Alberta Human Rights Commission, 2021, p. 8), and the New Brunswick and Ontario guidelines refer to the need for disabled students to meet the essential requirements of their programs. Educators are expected to carefully consider what knowledge and skills are essential for students to have obtained in order to pass a course and earn their degree, when determining which approaches can be taken to ensure access for disabled students (see Norris et al., 2023 for practical advice on this process).

Accessibility through student accommodations

Most Canadian colleges and universities have a designated office to serve disabled students and help educators meet the duty to accommodate them. Such disability services work with students to collect documentation regarding their disability, identify their needs and limitations in the academic context, and provide recommendation of specific accommodations (Condra et al., 2015). There are a variety of accommodations that can be recommended, targeting: the delivery of course content (e.g., captions required for video; copies of lecture material provided in advance), classroom structure and activity (e.g., priority seating; permission to take breaks), the format of assessments (e.g., typing responses to a written exam; recording an oral presentation), the timing of assessments (e.g., an extension on an essay; extra time on an exam), and other aspects of a course (e.g., Fichten et al., 2022; Norris & Karasewich, 2022; Parsons et al., 2020). It is typically the responsibility of disabled students to request such accommodations from their instructors and for instructors to make the appropriate arrangements. A written recommendation from disability services can act as a layer of protection for disabled students during this process, allowing them to keep the details of their disability private and focus on their needs (Alberta Human Rights Commission, 2021; New Brunswick Human Rights Commission, 2017; Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2004).

There are several issues with the standard approach of providing individual student accommodations. First, it is important to recognize that registering with disability services can be a long and effortful process, and that many students face additional barriers to getting the support they need. Formal assessments for some types of disability can have a high cost (e.g., learning disabilities), and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are likely to have trouble navigating this cost and the bureaucratic process of obtaining accommodations (Waterfield & Whelan, 2017). Students may also be wary of disclosing details of their disability, even to staff within disability services, for fear that instructors, staff, and peers may view them negatively or discriminate against them (Bruce & Aylward, 2021; Lindsay et al., 2018; Toutain, 2019). In response to such concerns, the Ontario Human Rights Commission has recently changed their guidelines to allow students with mental-health disabilities to register with disability services without needing to provide a formal diagnostic label – instead, their healthcare provider must only confirm the presence of a disability and identify limitations that would impact their academics (Condra & Condra, 2015; Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2016). This change puts the onus on healthcare providers to determine the ways that a student’s disability could impair them at school, but many do not have adequate training to do so, which may lead to students receiving accommodations that are inappropriate for their needs (Harrison et al., 2018).

Many post-secondary institutions in Canada are facing financial difficulties, particularly in Ontario where the provincial government has kept tuition fees frozen for several years while also cutting funding (Usher & Balfour, 2023). This puts increased pressure on disability services, who have already been strained to support increasing numbers of disabled students, and may force them to settle for recommending accommodations that are less tailored, more cost-effective, and require less time to process (Deloitte, 2017; Sokal & Vermette, 2017; Toutain, 2019). Instructors are also feeling strained by having to implement high numbers of accommodations with inadequate knowledge or support, leading some to hold negative attitudes toward disabled students or respond in inappropriate ways (e.g., Sniatecki et al., 2015; Sokal, 2016). Overall, the accommodations approach to accessibility requires a large amount of resources and time from students, instructors, and disability services alike, without necessarily meeting the needs of disabled students.

Accessibility through universal design

The accommodations approach to accessibility is reactive –instructors and disability services respond to the individual needs of students as they arise – but accessibility in higher education can be approached proactively. To do so requires a change in how disability is viewed: instead of the medical model, that focuses on disability as an impairment students bring into the classroom, the social model focuses on the classroom environment itself and the barriers it creates for disabled students (Olkin, 2002; World Health Organization, 2021). Instructors can take steps to remove such barriers through universal design (Fleet & Kondrashov, 2019).

Universal design as a concept emerged in many different forms around the world during the mid-twentieth century, but the term itself originated in architecture, where Ron Mace (future founder of the Center for Universal Design) used it to describe the process of designing buildings, products, and services to be accessible to the greatest extent possible by everyone (Ostroff, 2011). Universal design considers diverse needs in all forms. For example, creating a shallow ramp up to a building’s entrance allows access not only to disabled people who use assistive devices like wheelchairs, but also to parents with strollers, small children, and anyone else who may have short- or long-term difficulty using stairs. Since the 1990s, multiple methods have been created to apply principles of universal design to education – including, but not limited to: Universal Instructional Design (UID), Universal Design for Instruction (UDI), Universal Design in Education (UDE), and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (Burgstahler, 2023; CAST, 2018; McGuire et al., 2006; Pliner & Johnson, 2004; Scott et al., 2003). In all of these methods, instructors are encouraged to include more flexibility in their lessons, activities, and assessments, and to not only expect but welcome differences among their students. When instructors design their courses to anticipate the needs of disabled students, they can reduce the number of accommodations they provide on an individual basis, such as in the examples listed in Table 1, below. Importantly, because universal design applies to all students in a course, disabled students will benefit even if they are not registered with disability services, for whatever reason (e.g., lacking the means to get documentation, processing delays, lacking awareness of supports, fear of discrimination, etc.; Li et al., 2020; Lindsay et al., 2018; Waterfield & Whelan, 2017).

Table 1

Accommodations and Universal Design

| Student Accommodation | Universal Design |

| A student registered with disability services is given class material in advance so that they can access it using adaptive technology or have it adapted into an accessible format | All students in a course are given class material in advance, which was created following accessibility guidelines |

| A student registered with disability services is given an alternative written assignment in place of oral participation during class | All students in a course are given multiple opportunities to participate, including both oral and written options |

| A student registered with disability services is given an additional thirty minutes to write a one-hour exam | All students in a course are given two hours to write an exam that would take the average student one hour to write |

| A student registered with disability services is given a three-day extension for an essay | All students in a course are given a three-day grace period to submit an essay without penalty |

Note. This table presents examples only of student accommodations that could potentially be provided at the course-level, through universal design.

In higher education, individual courses are typically designed by the same faculty member or graduate student acting as the instructor for that term. The decision of whether or not to apply universal design to a course thus rests with the instructor. There are many reasons that an instructor may be wary of universal design, including: limited knowledge of how to implement it, a lack of time or resources, or minimal institutional support for trying new teaching methods (Hills et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022). Some of the changes encouraged by universal design require more effort than others. For example, in a class that incorporates many videos into lessons, adding accurate captions will require time and skill using software that instructors may not have, but could be supported through (Kent et al., 2018). Ultimately, instructors will be more likely to implement universal design in their courses, and more effective in their practice, when they have support from their institution, through: training workshops, shared resources, expert help with creating accessible formats, rewards for their efforts, etc. (Fleet & Kondrashov, 2019; Hills et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020).

Universal design and individual need

Although education scholars often present universal design as an alternative to student accommodations, it does not actually promise to meet every possible need for accessibility (McGuire et al., 2006). In some cases, universal design practices may even exacerbate or create new barriers for disabled students. For example, if an instructor makes the format of an assessment flexible by allowing students to complete a written assignment in place of an oral presentation, many students may choose the alternative due to anxiety and then miss an opportunity to develop important skills in both oral communication and anxiety management (e.g., Griful-Freixenet et al., 2017). Where giving oral presentations is deemed an essential skill for the course or program, instructors should instead consider other methods of providing students with flexibility and support, such as by giving them opportunities to practice in low-stakes environments or the option to record a presentation in a video format.

The accommodations that are recommended for disabled students can vary greatly, and it is not always possible, or practical, for instructors to meet every accommodation through course design. For example, when an instructor has determined that a monitored, timed exam would be the best way of assessing student knowledge, it may be feasible to cover any accommodations that recommended providing extra time for disabled students by giving all students in the course double the amount of time they would normally give to write the exam. It would be far less feasible for the instructor to administer the exam in a space that covers all accommodations related to room structure (e.g., no fluorescent lighting) or size (e.g., private or semi-private rooms) – instead, separate arrangements would still need to be made for students with those accommodations. Such an approach aligns with the Ontario Human Rights Commission’s (2004) three-step recommendation for ensuring disabled students are able to participate in education to the fullest extent possible:

- Promoting Inclusive/Universal Design

All aspects of education – courses, facilities, policies, etc. – should be designed by instructors and institutions to meet accessibility standards from the outset.

- Removing Barriers

Where barriers already exist, instructors and institutions should make changes to remove them, up to the point of undue hardship.

- Accommodating Remaining Needs

Where barriers cannot be removed, alternatives should be explored through individual student accommodations.

Accessibility beyond the classroom

A button that can be pressed to open an automatic door does not make a room accessible if it is in a building that can only be entered via stairs. Similarly, students’ disabilities do not start or end at the doors of their classrooms, and neither should our efforts to make higher education accessible. First, disabled students need more support in transitioning to post-secondary education and navigating differences between the individual education plans they may have received in secondary school and the accommodations process of higher education (Parsons et al., 2020; Parsons et al., 2021). Programs could also be developed to help disabled students with the unique barriers they face outside of their academics, where they may feel excluded from their campus communities or face stigma from non-disabled peers (Shpigelman et al., 2022; Maconi et al., 2019). Finally, disabled students should be provided with targeted support for transitioning from postsecondary education to the workforce, where they are more likely to have difficulty finding employment compared to their non-disabled peers and where they may face discrimination (Stewart & Schwartz, 2018). Disabled students can greatly benefit from work-experience programs that give them opportunities to practice career skills and connect with employers, but only a minority of Canadian institutions offer programs that are accessible to them (Bellman et al., 2014; Gatto et al., 2021; Mowreader, 2024).

Summary

Disabled Canadians have a right to pursue higher education. It is necessary for post-secondary institutions to provide an accessible learning environment that allows disabled students to fully participate and show they have mastered the essential requirements of their program. This is no simple feat, however, with limited funding and increasing numbers of students in need. The standard, individual accommodations approach to accessibility can require a high amount of time and effort for all involved – students, instructors, and staff – and will leave some disabled students with no or inadequate support. Approaching accessibility from the course level, through universal design, has the potential to provide support for disabled students with less reliance on individual accommodations, though it will not eliminate individual need entirely. Instructors should be provided with more support to implement universal design in their courses and respond effectively to remaining needs for accommodation. Finally, post-secondary institutions must look outside of the classroom to ensure they are providing an accessible environment for disabled students to transition into higher education, participate in all aspects of campus life, and prepare to enter the workforce.

References

Accessibility Act, S.N.S., c. 2 (2017). https://nslegislature.ca/legc/bills/62nd_3rd/3rd_read/b059.htm

Accessibility Act, S.N.L., c. A-1.001 (2021). https://www.assembly.nl.ca/Legislation/sr/statutes/a01-001.htm

Accessible British Columbia Act, S.B.C., c. 19 (2021). https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/21019

Act to secure handicapped persons in the exercise of their rights with a view to achieving social, school, and workplace integration, C.Q.L.R., c. E-20.1 (2004). https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/document/lc/E-20.1?langCont=en

Alberta Human Rights Commission. (2021). Duty to accommodate students with disabilities in post-secondary educational institutions. https://albertahumanrights.ab.ca/what-are-human-rights/about-human-rights/duty-to-accommodate/

Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq. (1990). https://www.ada.gov/law-and-regs/ada/

Bellman, S., Burgstahler, S., & Ladner, R. (2014). Work-based learning experiences help students with disabilities transition to careers: A case study of University of Washington projects. Work, 48, 399-405. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-131780

Berrigan, P., Scott, C. W. M., & Zwicker, J. D. (2023). Employment, education, and income for Canadians with developmental disability: Analysis from the 2017 Canadian survey on disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53, 580-592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04603-3

Bruce, C., & Aylward, M. L. (2021). Disability and self-advocacy experiences in university learning contexts. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 23(1), 14-26. https://doi.org/10.16993/sjdr.741

Burgstahler, S. E. (2023). Universal design in STEM education. In R. J. Tierney, F. Rizvi, & K. Ercikan (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (4th ed., Vol. 11, pp. 326-333). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818630-5.13074-X

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 15, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

Canadian Human Rights Commission. (2017). Left out: Challenges faced by persons with disabilities in Canada’s schools. https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/en/resources/publications/left-out-challenges-faced-persons-disabilities-canadas-schools

Canadian Human Rights Commission. (2023). Overview of the Accessible Canada Act. Retrieved May 4, 2024, from https://www.accessibilitychrc.ca/en/overview-accessible-canada-act

Canadian University Survey Consortium. (n.d.). CUSC Master Reports. Retrieved May 4, 2024, from https://cusc-ccreu.ca/wordpress/?page_id=32&lang=en

CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines, version 2.2. Retrieved May 4, 2024, from https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Condra, M., & Condra, E. M. (2015). Recommendations for documentation standards and guidelines for academic accommodations for post-secondary students in Ontario with mental health disabilities. Queen’s University and St. Lawrence College Partnership Project.

Condra, M., Dineen, M., Gauthier, S., Gills, H., Jack-Davies, A., & Condra, E. (2015). Academic accommodations for postsecondary students with mental health disabilities in Ontario, Canada: A review of the literature and reflections on emerging issues. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28(3), 277-291.

Deloitte Canada. (2017). Enabling sustained student success support for students at risk in Ontario’s colleges. https://www.collegesontario.org/en/resources/enabling-sustained-student-success

Dunn, D. S., & Andrews, E. E. (2015). Person-first and identity-first language: Developing psychologists’ cultural competence using disability language. American Psychologist, 70(3), 255-264. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038636

Fichten, C., Havel, A., Jorgensen, M., Wileman, S., & Budd, J. (2022). Twenty years into the 21st century – Tech-related accommodations for college students with mental health and other disabilities. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 10(4), 16-29. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v10i4.5594

Fleet, C., & Kondrashov, O. (2019). Universal design on university campuses: A literature review. Exceptionality Education International, 29(1), 136-148.

Gatto, L. E., Pearce, H., Antonie, L., & Plesca, M. (2021). Work integrated learning resources for students with disabilities: Are post-secondary institutions in Canada supporting this demographic to be career ready? Higher Education, Skills, and Work-Based Learning, 11(1), 125-143. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-08-2019-0106

Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K., Verstichele, M., & Andries, C. (2017). Higher education students with disabilities speaking out: Perceived barriers and opportunities of the universal design for learning framework. Disability and Society, 32(10), 1627-1649. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1365695

Harrison, A. G., Holmes, A., & Harrison, K. (2018). Medically confirmed functional impairment as proof of accommodation need in postsecondary education: Are Ontario’s campuses the bellwether of an inequitable decision-making paradigm? Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 187, 48-60.

Hills, M., Overend, A., & Hildebrandt, S. (2022). Faculty perspectives on UDL: Exploring bridges and barriers for broader adoption in higher education. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotlrcacea.2022.1.13588

Jacobs, L. (2023). Access to post-secondary education in Canada for students with disabilities. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law, 23(1-2), 7-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/13582291231174156

Kent, M., Ellis, K., Latter, N., & Peaty, G. (2018). The case for captioned lectures in Australian higher education. TechTrends, 62, 158-165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-017-0225-x

Li, Y., Zhang, D., Zhang, Q., & Dulas, H. (2020). University faculty attitudes and actions toward universal design: A literature review. Journal of Inclusive Postsecondary Education, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.13021/jipe.2020.2531

Lindsay, S., Cagliostro, E., & Carafa, G. (2018). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators of disability disclosure and accommodations for youth in post-secondary education. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 65(5), 526-556. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2018.1430352

Ma, J., Pender, M., & Welch, M. (2016). Education pays 2016: The benefits of higher education for individuals and society. College Board.

Maconi, M. L., Green, S. E., & Bingham, S. C. (2019). It’s not all about coursework: Narratives of inclusion and exclusion among university students receiving disability accommodations. In K. Sorgie & C. Forlin (Eds.) Promoting social inclusion: Co-creating environments that foster equity and belonging (pp. 181-194). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-363620190000013014

McGuire, J. M., Scott, S. S., & Shaw, S. F. (2006). Universal design and its applications in educational environments. Remedial and Special Education, 27(3), 166-175.

Moroz, N., Moroz, I., D’Angelo, M. S. (2020). Mental health services in Canada: Barriers and cost-effective solutions to increase access. Healthcare Management Forum, 33(6), 282-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0840470420933911

Morris, S., Fawcett, G., Brisebois, L., & Hughes, J. (2018). A demographic, employment with income profile of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over, 2017. Statistics Canada, 89-654-X2018002.

Mowreader, A. (2024, January 9). Career prep tip: Specialized programming for neurodiverse students. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/student-success/life-after-college/2024/01/09/colleges-offer-career-support-students

New Brunswick Human Rights Commission. (2017). Guideline on accommodating students with disabilities in post-secondary institutions. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/news/news_release.2014.10.1193.html

Norris, M. E., & Karasewich, T. A. (2022). A proactive approach to navigating student accommodations. Disability Compliance for Higher Education, 28(5), 5. https://doi.org/10.1002/dhe.31404

Norris, M. E., Karasewich, T. A., & Kenkel, H. K. (2024). Academic integrity and accommodations: The intersections of ethics and flexibility. In S. E. Eaton (Ed.), Handbook of academic integrity (2nd ed.) (pp. 249-268). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-079-7_92-1

Olkin, R. (2002). Could you hold the door for me? Including disability in diversity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8(2), 130-137. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.8.2.130

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2004). Guidelines on accessible education. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/annual-report-2011-2012-human-rights-next-generation/guidelines-accessible-education

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2016). New documentation guidelines for accommodating students with mental health disabilities. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/news_centre/new-documentation-guidelines-accommodating-students-mental-health-disabilities

Ostroff, E. (2011). Universal design: An evolving paradigm. In W. F. E. Preiser & K. H. Smith (Eds.) Universal design handbook (2nd ed.) (pp. 1.3-1.11). McGraw-Hill.

Parsons, J., McColl, M. A., Martin, A., & Rynard, D. (2020). Students with disabilities transitioning from high school to university in Canada: Identifying changing accommodations. Exceptionality Education International, 30(3), 64-81.

Parsons, J., McColl, M. A., Martin, A. K., & Rynard, D. W. (2021). Accommodations and academic performance: First-year university students with disabilities. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 51(1), 41-56. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.vi0.188985

Pliner, S. M., & Johnson, J. R. (2004). Historical, theoretical, and foundational principles of universal instructional design in higher education. Equity and Excellence in Education, 37, 105-113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665680490453913

Scott, S. S., McGuire, J. M., & Foley, T. E. (2003). Universal design for instruction: A framework for anticipating and responding to disability and other diverse learning needs in the college classroom. Equity & Excellence in Education, 36(1), 40–49.

Shpigelman, C., Mor, S., Sachs, D., & Schreuer, N. (2022). Supporting the development of students with disabilities in higher education: Access, stigma, identity, and power. Studies in Higher Education, 47(9), 1776-1791. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1960303

Sniatecki, J. L., Perry, H. B., & Snell, L. H. (2015). Faculty attitudes and knowledge regarding college students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28(3), 259-275.

Sokal, L. (2016). Five windows and a locked door: University accommodation responses to students with anxiety disorders. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.5206/cjostl-rcacea.2016.1.10

Sokal, L., & Vermette, L. A. (2017). Double time? Examining extended testing time accommodations (ETTA) in postsecondary settings. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 30(2), 185-200.

Statistics Canada. (2022). Canadian survey on disability (CSD). Retrieved May 4, 2024, from https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=1329901

Statistics Canada. (2023). Canadian survey on disability, 2017 to 2022. The Daily, 11-001-X. Retrieved May 4, 2024, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/231201/dq231201b-eng.htm

Stewart, J. M., & Schwartz, S. (2018). Equal education, unequal jobs: College and university students with disabilities. Industrial Relations, 73(2), 369-394. https://doi.org/10.7202/1048575ar

The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code, S.S., c. S-24.2 (2018). https://saskatchewanhumanrights.ca/your-rights/saskatchewan-human-rights-code/

Toutain, C. (2019). Barriers to accommodations for students with disabilities in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 32(3), 297-310.

Usher, A., & Balfour, J. (2023). The state of postsecondary education in Canada, 2023. Higher Education Strategy Associates.

Waterfield, B., & Whelan, E. (2017). Learning disabled students and access to accommodations: Socioeconomic status, capital, and stigma. Disability and Society, 32(7), 986-1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1331838

World Health Organization. (2021). WHO policy on disability (pp. 1-11). https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240020627

How to Cite

Karasewich, T. A. (2024). Accessibility in higher education. In M. E. Norris and S. M. Smith (Eds.), Leading the Way: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education. Kingston, ON: Queen’s University, eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/futureofhighereducation/chapter/accessibility-in-higher-education/

- In this chapter, I will be primarily using identity-first language (e.g., ‘disabled person’) instead of person-first (e.g., ‘person with disability’), to follow the lead of disability studies and acknowledge the ways in which environments that are built for the dominant, non-disabled, majority create barriers that disable (Dunn & Andrews, 2015; Fleet & Kondrashov, 2019). ↵