4 Framing Concepts: Disability Justice in Higher Education

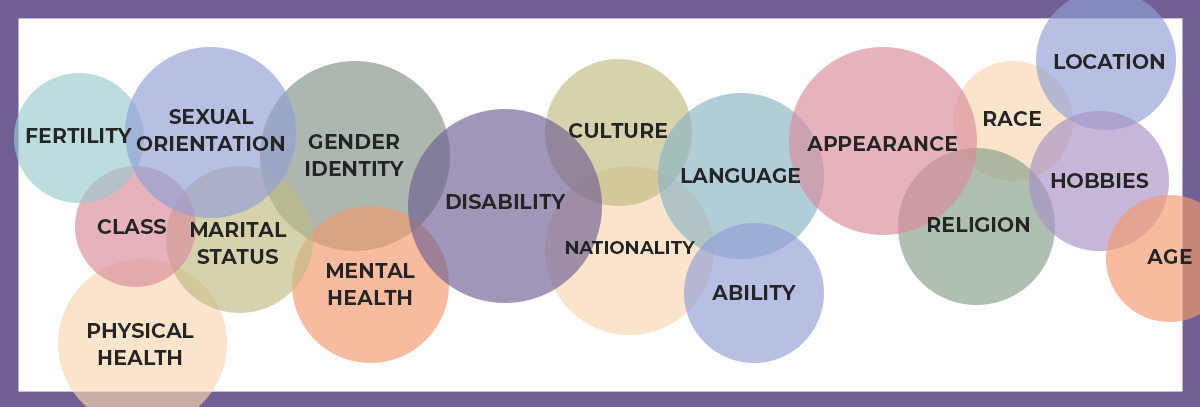

The authors are working within a framework of disability justice, which views disability as not a problem to be solved or overcome, but one of many dimensions within intersectional identities. The framework is useful when considering the history of disabled bodies in higher education institutions, reframing disabled students as assets who make up a learning community in the classroom, and how pedagogy can be a site of praxis.

Accommodations are commonly viewed as what Dr. Jay Dolmage terms a “retrofit” solution, which is “intended to simply temporarily even the playing field for them in a single class or activity… these retrofits are not designed for people to live and thrive with a disability, but rather to temporarily make the disability go away. The aspiration here is not to empower students to achieve with disability, but to achieve around disability or against it, or in spite of it” (Dolmage 70). The accommodations process should go beyond a rights-based approach, which only does the bare minimum – how many times has a time accommodation been dutifully entered into onQ and hope that takes care of the problem? We encourage the reader to abandon this deficit model of considering disability and instead approach this work with a disability justice mindset, which is key to unlocking what we owe each other in the classroom: a symbiotic relationship that nurtures each other and embraces the possibilities of a learning community.

In this resource, we encourage readers to rethink and resist ableist frameworks. Higher education is not only a site of oppression for disabled students, but ableism is reproduced in the design of education (see: Dolmage). The labour of implementing accommodations has been designed around ableist, normative, rights-based frameworks. Instead, we invite the readers of this resource to approach implementing accommodations from a new perspective. It may be useful to consider the concept of collective access: designing a course or assessment that each student can access and engage with in multiple modalities serves the entire learning community and allows for engagement with each other and with the content. We invite readers to consider what and who accommodations serve and to reframe it not as ‘accommodating’ as per the status quo but thinking of it as providing more inclusive access to everyone. Access can look like (but is not limited to) the following examples:

“needs and experiences [which] can be related to economics, sensory issues, trauma, care of dependents, housing, immigration status, and so on. When setting up a class or event, some common access needs might include varied seating, desks/tables, adapters for different kinds of technology, a microphone, presentation slides, childcare, children’s activities, dietary needs, scent-free spaces, ASL interpretation, lighting sensitivity, nonvisual options for visual materials and/or audio describers, wheelchair accessibility, all-gender bathrooms, and armless seating. What else might a body need to participate more fully in your… course?” (Dorrance, Havard, Luna, and Young 2023).

The labour of implementing accommodations remains ever-present but consider that “accommodation is the most basic act and art of teaching. It is not the exception we sometimes make in spite of learning, but rather the adaptations we continually make to promote learning” (Womack 2017). It is an opportunity for faculty to grow, evolve, be responsive, and shift to meet the whole of the learning community within the classroom, and not just those students who “happen to succeed within normative educational conditions” (Womack 2017). We hope that this guide acts as a helpful resource in navigating the accommodations system for the teaching team, who is ultimately responsible for creating and sustaining an accessible learning experience.