17.4 Magnetic Field Strength: Force on a Moving Charge in a Magnetic Field

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the effects of magnetic fields on moving charges.

- Use the right hand rule 1 to determine the velocity of a charge, the direction of the magnetic field, and the direction of the magnetic force on a moving charge.

- Calculate the magnetic force on a moving charge.

What is the mechanism by which one magnet exerts a force on another? The answer is related to the fact that all magnetism is caused by current, the flow of charge. Magnetic fields exert forces on moving charges, and so they exert forces on other magnets, all of which have moving charges.

Right Hand Rule 1

The magnetic force on a moving charge is one of the most fundamental known. Magnetic force is as important as the electrostatic or Coulomb force. Yet the magnetic force is more complex, in both the number of factors that affects it and in its direction, than the relatively simple Coulomb force. The magnitude of the magnetic force [latex]F[/latex] on a charge [latex]q[/latex] moving at a speed [latex]v[/latex] in a magnetic field of strength [latex]B[/latex] is given by

[latex]F = \text{qvB} \text{sin} \theta ,[/latex]

where [latex]\theta[/latex] is the angle between the directions of [latex]\textbf{v}[/latex] and [latex]\textbf{B} .[/latex] This force is often called the Lorentz force. In fact, this is how we define the magnetic field strength [latex]B[/latex]—in terms of the force on a charged particle moving in a magnetic field. The SI unit for magnetic field strength [latex]B[/latex] is called the tesla (T) after the eccentric but brilliant inventor Nikola Tesla (1856–1943). To determine how the tesla relates to other SI units, we solve [latex]F = \text{qvB} \text{sin} \theta[/latex] for [latex]B[/latex].

[latex]B = \frac{F}{\text{qv} \text{sin} \theta}[/latex]

Because [latex]\text{sin} \theta[/latex] is unitless, the tesla is

[latex]\text{1 T} = \frac{\text{1 N}}{C \cdot \text{m}/\text{s}} = \frac{\text{1 N}}{A \cdot m}[/latex]

(note that C/s = A).

Another smaller unit, called the gauss (G), where [latex]1 G = \text{10}^{- 4} T[/latex], is sometimes used. The strongest permanent magnets have fields near 2 T; superconducting electromagnets may attain 10 T or more. The Earth’s magnetic field on its surface is only about [latex]5 \times \text{10}^{- 5} T[/latex], or 0.5 G.

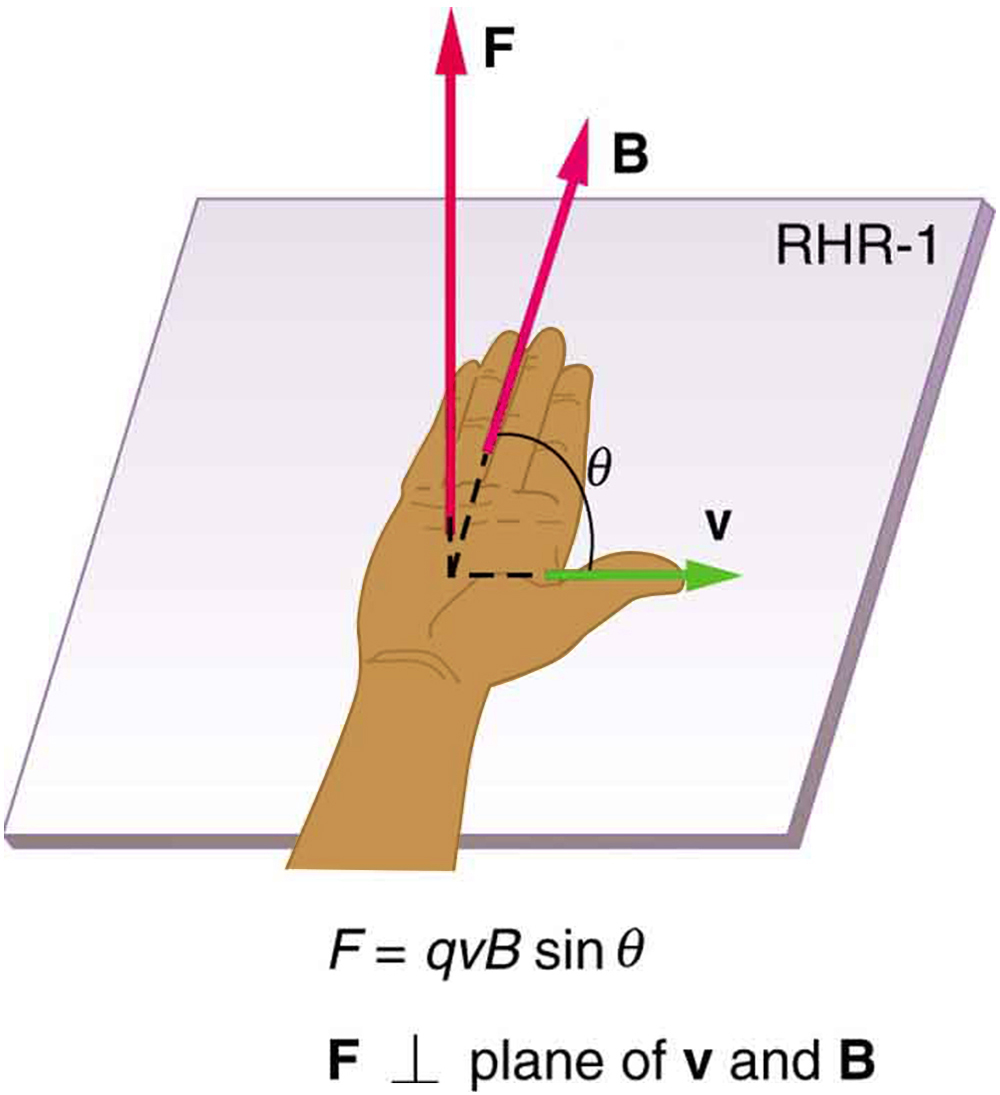

The direction of the magnetic force [latex]\textbf{F}[/latex] is perpendicular to the plane formed by [latex]\textbf{v}[/latex] and [latex]\textbf{B}[/latex], as determined by the right hand rule 1 (or RHR-1), which is illustrated in Figure 17.16. RHR-1 states that, to determine the direction of the magnetic force on a positive moving charge, you point the thumb of the right hand in the direction of [latex]\textbf{v}[/latex], the fingers in the direction of [latex]\textbf{B}[/latex], and a perpendicular to the palm points in the direction of [latex]\textbf{F}[/latex]. One way to remember this is that there is one velocity, and so the thumb represents it. There are many field lines, and so the fingers represent them. The force is in the direction you would push with your palm. The force on a negative charge is in exactly the opposite direction to that on a positive charge.

Image Description

The image illustrates the Right-Hand Rule 1 (RHR-1) in physics. It shows a hand with fingers pointing upwards, palm facing left, and the thumb pointing to the right. Three vectors are represented:

- F: A red arrow pointing upwards, representing force.

- B: A red arrow pointing outwards from the palm, representing magnetic field.

- v: A green arrow aligned with the thumb pointing to the right, representing velocity.

An angle θ is depicted between vectors v and B. The caption includes the formula F = qvB sin θ, indicating the force is perpendicular to the plane of v and B.

Making Connections: Charges and Magnets

There is no magnetic force on static charges. However, there is a magnetic force on moving charges. When charges are stationary, their electric fields do not affect magnets. But, when charges move, they produce magnetic fields that exert forces on other magnets. When there is relative motion, a connection between electric and magnetic fields emerges—each affects the other.

Example 17.1

Calculating Magnetic Force: Earth’s Magnetic Field on a Charged Glass Rod

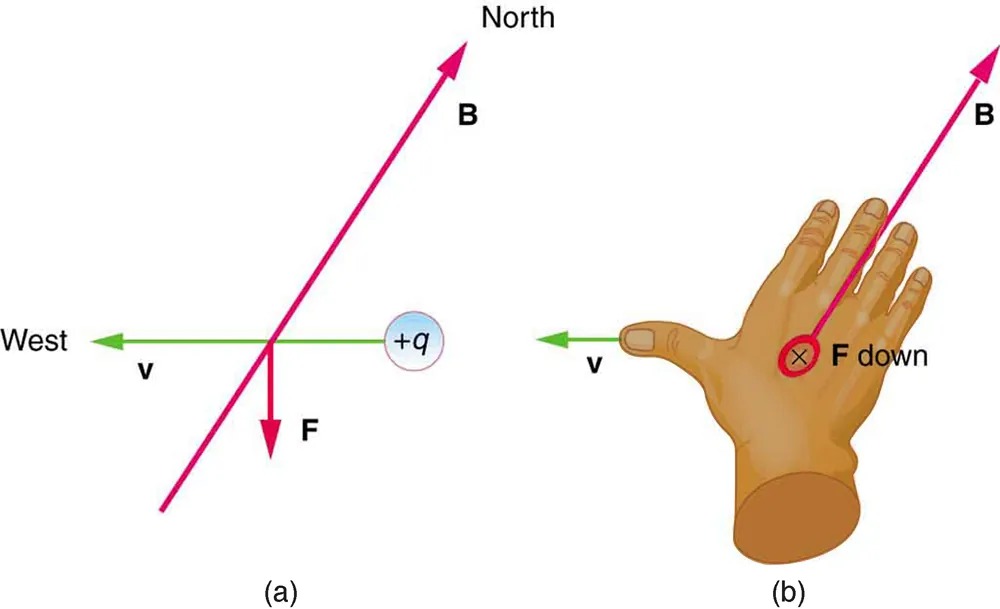

With the exception of compasses, you seldom see or personally experience forces due to the Earth’s small magnetic field. To illustrate this, suppose that in a physics lab you rub a glass rod with silk, placing a 20-nC positive charge on it. Calculate the force on the rod due to the Earth’s magnetic field, if you throw it with a horizontal velocity of 10 m/s due west in a place where the Earth’s field is due north parallel to the ground. (The direction of the force is determined with right hand rule 1 as shown in Figure 17.17.)

Figure 17.17 A positively charged object moving due west in a region where the Earth’s magnetic field is due north experiences a force that is straight down as shown. A negative charge moving in the same direction would feel a force straight up. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image consists of two diagrams labeled as (a) and (b), illustrating the right-hand rule for determining the direction of force on a positive charge in a magnetic field.

Diagram (a):

- A particle with a positive charge (+q) is moving to the west, shown by a green arrow labeled “v” pointing left.

- A magnetic field (B) is directed towards the north, indicated by a red arrow pointing upwards and right.

- The resultant force (F) on the charged particle is directed downwards, indicated by a red arrow pointing straight down.

Diagram (b):

- An open right hand is shown with the fingers extended.

- The thumb points west, representing the direction of velocity “v”.

- The fingers point north, representing the direction of the magnetic field “B”.

- The palm faces downward, showing the direction of the force “F down” on the positive charge, marked by a circular symbol with an “x”.

Strategy

We are given the charge, its velocity, and the magnetic field strength and direction. We can thus use the equation [latex]F = \text{qvB} \text{sin} \theta[/latex] to find the force.

Solution

The magnetic force is

[latex]F = \text{qvB} \text{sin} \theta .[/latex]

We see that [latex]\text{sin} \theta = 1[/latex], since the angle between the velocity and the direction of the field is [latex]\text{90}º[/latex]. Entering the other given quantities yields

[latex]\begin{eqnarray*}F & = & \left(\text{20} \times \text{10}^{–9} C\right) \left(\text{10 m}/\text{s}\right) \left(5 \times \text{10}^{–5} T\right) \\ & = & 1 \times \text{10}^{–\text{11}} \left(C \cdot \text{m}/\text{s}\right) \left(\frac{N}{C \cdot \text{m}/\text{s}}\right)\\ &=& 1 \times \text{10}^{–\text{11}} N.\end{eqnarray*}[/latex]

Discussion

This force is completely negligible on any macroscopic object, consistent with experience. (It is calculated to only one digit, since the Earth’s field varies with location and is given to only one digit.) The Earth’s magnetic field, however, does produce very important effects, particularly on submicroscopic particles. Some of these are explored in Force on a Moving Charge in a Magnetic Field: Examples and Applications.