15.3 Coulomb’s Law

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State Coulomb’s law in terms of how the electrostatic force changes with the distance between two objects.

- Calculate the electrostatic force between two charged point forces, such as electrons or protons.

- Compare the electrostatic force to the gravitational attraction for a proton and an electron; for a human and the Earth.

Figure 15.16 This NASA image of Arp 87 shows the result of a strong gravitational attraction between two galaxies. In contrast, at the subatomic level, the electrostatic attraction between two objects, such as an electron and a proton, is far greater than their mutual attraction due to gravity. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Through the work of scientists in the late 18th century, the main features of the electrostatic force—the existence of two types of charge, the observation that like charges repel, unlike charges attract, and the decrease of force with distance—were eventually refined, and expressed as a mathematical formula. The mathematical formula for the electrostatic force is called Coulomb’s law after the French physicist Charles Coulomb (1736–1806), who performed experiments and first proposed a formula to calculate it.

Coulomb’s Law

[latex]F = k \frac{\left|\right. q_{1} q_{2} \left|\right.}{r^{2}} .[/latex]

Coulomb’s law calculates the magnitude of the force [latex]F[/latex] between two point charges, [latex]q_{1}[/latex] and [latex]q_{2}[/latex], separated by a distance [latex]r[/latex]. In SI units, the constant [latex]k[/latex] is equal to

[latex]k = 8 . \text{988} \times \text{10}^{9} \frac{\text{N} \cdot \text{m}^{2}}{\text{C}^{2}} \approx 8 . \text{99} \times \text{10}^{9} \frac{\text{N} \cdot \text{m}^{2}}{\text{C}^{2}} .[/latex]

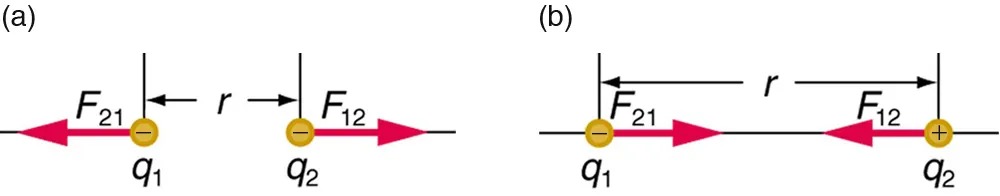

The electrostatic force is a vector quantity and is expressed in units of newtons. The force is understood to be along the line joining the two charges. (See Figure 15.17.)

Although the formula for Coulomb’s law is simple, it was no mean task to prove it. The experiments Coulomb did, with the primitive equipment then available, were difficult. Modern experiments have verified Coulomb’s law to great precision. For example, it has been shown that the force is inversely proportional to distance between two objects squared [latex]\left(F \propto 1 / r^{2}\right)[/latex] to an accuracy of 1 part in [latex]\text{10}^{\text{16}}[/latex]. No exceptions have ever been found, even at the small distances within the atom.

Figure 15.17 The magnitude of the electrostatic force [latex]F[/latex] between point charges [latex]q_{1}[/latex] and [latex]q_{2}[/latex] separated by a distance [latex]r[/latex] is given by Coulomb’s law. Note that Newton’s third law (every force exerted creates an equal and opposite force) applies as usual—the force on [latex]q_{1}[/latex] is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the force it exerts on [latex]q_{2}[/latex]. (a) Like charges. (b) Unlike charges. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image contains two diagrams labeled (a) and (b), illustrating force interactions between charges.

Diagram (a):

– Two negatively charged particles are shown, labeled \( q_1 \) and \( q_2 \).

– The particles are separated by a distance labeled \( r \).

– An arrow labeled \( F_{21} \) points leftward from \( q_2 \) towards \( q_1 \), indicating the force exerted on \( q_1 \).

– An arrow labeled \( F_{12} \) points rightward from \( q_1 \) towards \( q_2 \), indicating the force exerted on \( q_2 \).

– Both force arrows are depicted in red and positioned parallel to each other.

Diagram (b):

– The charges \( q_1 \) and \( q_2 \) are depicted again, but this time \( q_1 \) is negative and \( q_2 \) is positive.

– The distance between the charges is labeled \( r \).

– An arrow labeled \( F_{21} \) points leftward from \( q_2 \) towards \( q_1 \), representing the force on \( q_1 \).

– An arrow labeled \( F_{12} \) points rightward from \( q_1 \) towards \( q_2 \), representing the force on \( q_2 \).

– The forces are indicated by red arrows and positioned parallel to each other, just as in diagram (a).

Example 15.1

How Strong is the Coulomb Force Relative to the Gravitational Force?

Compare the electrostatic force between an electron and proton separated by [latex]0 . \text{530} \times \text{10}^{- \text{10}} \text{m}[/latex] with the gravitational force between them. This distance is their average separation in a hydrogen atom.

Strategy

To compare the two forces, we first compute the electrostatic force using Coulomb’s law, [latex]F = k \frac{\left|\right. q_{1} q_{2} \left|\right.}{r^{2}}[/latex]. We then calculate the gravitational force using Newton’s universal law of gravitation. Finally, we take a ratio to see how the forces compare in magnitude.

Solution

Entering the given and known information about the charges and separation of the electron and proton into the expression of Coulomb’s law yields

[latex]F = k \frac{\left|\right. q_{1} q_{2} \left|\right.}{r^{2}}[/latex]

[latex]= {\small\left(8.99 \times \text{ 10}^{9} \text{N} \cdot \text{ m}^{2} / \text{C}^{2}\right)} \times \frac{\left(\right. \text{1}.\text{60} \times \text{ 10}^{–\text{19}} \text{C} \left.\right) \left(\right. 1.60 \times \text{ 10}^{–\text{19 }} \text{C} \left.\right)}{\left(\right. 0.530 \times \text{ 10}^{–\text{10}} \text{m} \left.\right)^{2}} \\[/latex]

Thus the Coulomb force is

[latex]F = \text{8}.\text{19} \times \text{ 10}^{–\text{8}} \text{N} .[/latex]

The charges are opposite in sign, so this is an attractive force. This is a very large force for an electron—it would cause an acceleration of [latex]8.99 \times \text{10}^{\text{22}} \text{m} / \text{s}^{2}[/latex](verification is left as an end-of-section problem).The gravitational force is given by Newton’s law of gravitation as:

[latex]F_{G} = G \frac{mM}{r^{2}} ,[/latex]

where [latex]G = 6.67 \times \text{10}^{- \text{11}} \text{N} \cdot \text{m}^{2} / \text{kg}^{2}[/latex]. Here [latex]m[/latex] and [latex]M[/latex] represent the electron and proton masses, which can be found in the appendices. Entering values for the knowns yields

[latex]{\small\begin{align*}F_{G} &= \left(\right. 6.67 \times \text{ 10}^{– \text{11}} \text{N} \cdot \text{m}^{2} / \text{kg}^{2} \left.\right)\\[1.2ex]&\text{ }\;\;\; \times \frac{\left(\right. 9.11 \times \text{ 10}^{–\text{31}} \text{kg} \left.\right) \left(\right. 1.67 \times \text{10}^{–\text{27}} \text{kg} \left.\right)}{\left(\right. 0.530 \times \text{ 10}^{–\text{10}} \text{m} \left.\right)^{2}}\\[1.5ex] &= 3.61 \times \text{ 10}^{–\text{47}} \text{N}\end{align*}}[/latex]

This is also an attractive force, although it is traditionally shown as positive since gravitational force is always attractive. The ratio of the magnitude of the electrostatic force to gravitational force in this case is, thus,

[latex]\frac{F}{F_{G}} = \text{ 2} . \text{27 } \times \text{ 10}^{\text{39}} .[/latex]

Discussion

This is a remarkably large ratio! Note that this will be the ratio of electrostatic force to gravitational force for an electron and a proton at any distance (taking the ratio before entering numerical values shows that the distance cancels). This ratio gives some indication of just how much larger the Coulomb force is than the gravitational force between two of the most common particles in nature.

As the example implies, gravitational force is completely negligible on a small scale, where the interactions of individual charged particles are important. On a large scale, such as between the Earth and a person, the reverse is true. Most objects are nearly electrically neutral, and so attractive and repulsive Coulomb forces nearly cancel. Gravitational force on a large scale dominates interactions between large objects because it is always attractive, while Coulomb forces tend to cancel.