12.6 Convection

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the method of heat transfer by convection.

Convection is driven by large-scale flow of matter. In the case of Earth, the atmospheric circulation is caused by the flow of hot air from the tropics to the poles, and the flow of cold air from the poles toward the tropics. (Note that Earth’s rotation causes the observed easterly flow of air in the northern hemisphere). Car engines are kept cool by the flow of water in the cooling system, with the water pump maintaining a flow of cool water to the pistons. The circulatory system is used the body: when the body overheats, the blood vessels in the skin expand (dilate), which increases the blood flow to the skin where it can be cooled by sweating. These vessels become smaller when it is cold outside and larger when it is hot (so more fluid flows, and more energy is transferred).

The body also loses a significant fraction of its heat through the breathing process.

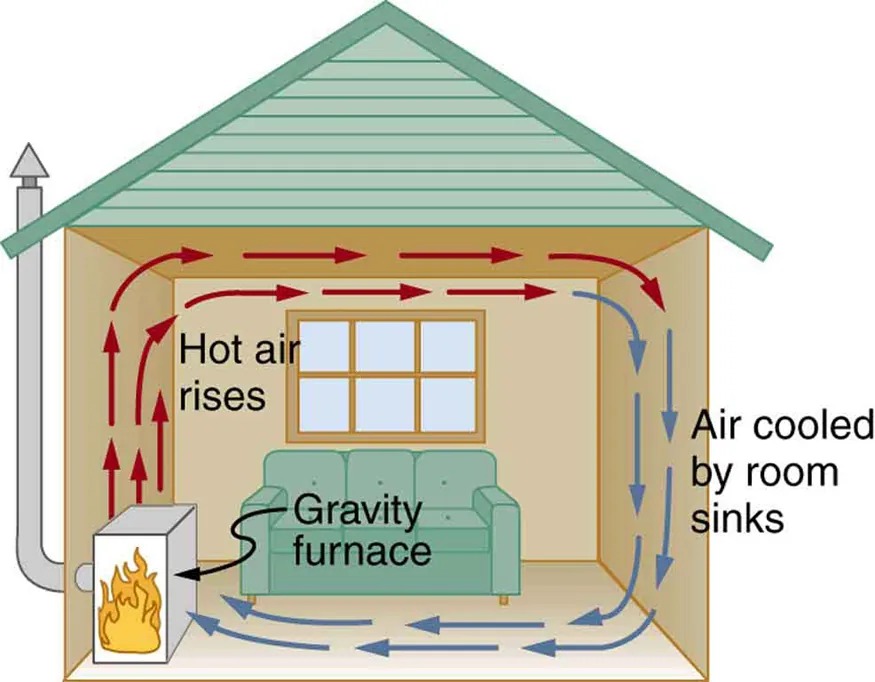

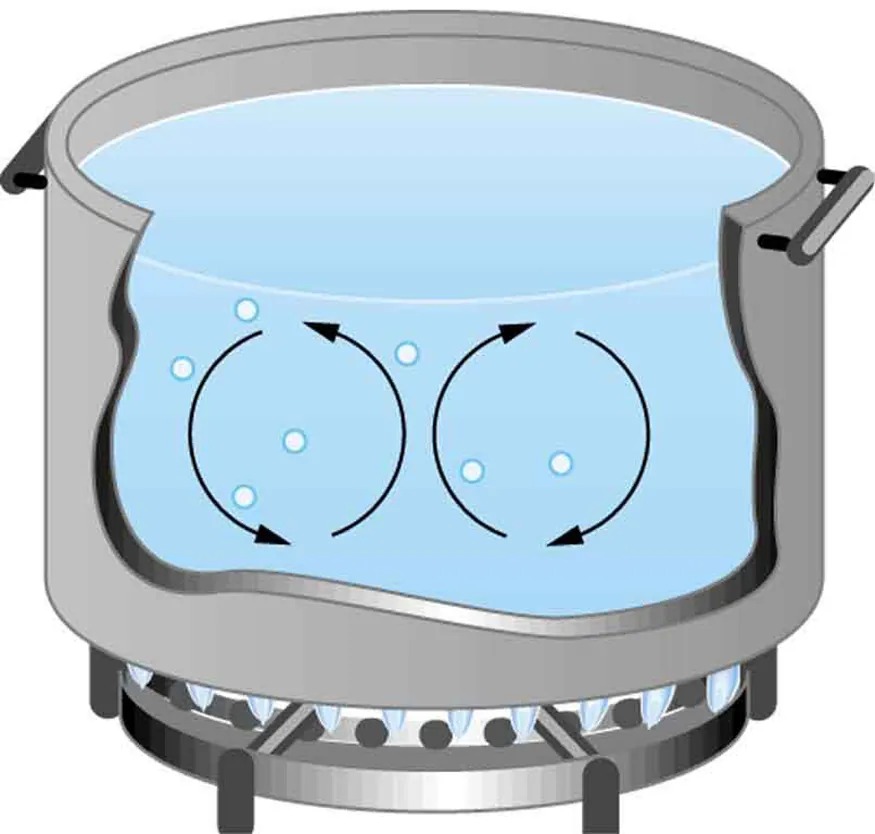

While convection is usually more complicated than conduction, we can describe convection and do some straightforward, realistic calculations of its effects. Natural convection is driven by buoyant forces: hot air rises because density decreases as temperature increases. The house in Figure 12.17 is kept warm in this manner, as is the pot of water on the stove in Figure 12.18. Ocean currents and large-scale atmospheric circulation transfer energy from one part of the globe to another. Both are examples of natural convection.

Figure 12.17 Air heated by the so-called gravity furnace expands and rises, forming a convective loop that transfers energy to other parts of the room. As the air is cooled at the ceiling and outside walls, it contracts, eventually becoming denser than room air and sinking to the floor. A properly designed heating system using natural convection, like this one, can be quite efficient in uniformly heating a home. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image is a diagram illustrating the operation of a gravity furnace system within a house. The interior is shown with a cross-section view.

– The furnace, depicted with a flame icon, is located at the bottom left of the house.

– Red arrows indicate the warm air rising from the furnace, flowing upwards and then horizontally across the ceiling.

– The label “Hot air rises” is placed near these arrows.

– As the air travels across the room, it begins to cool down and sinks, shown by blue arrows.

– The label “Air cooled by room sinks” is positioned near these blue arrows.

– A window is visible on the wall opposite the furnace.

– A green couch is placed against the same wall as the window.

– The blue arrows complete the cycle by returning the cooled air to the furnace at the floor level.

– The overall circulation shows how warm air is distributed by the gravity furnace throughout the room.

Figure 12.18 Convection plays an important role in heat transfer inside this pot of water. Once conducted to the inside, heat transfer to other parts of the pot is mostly by convection. The hotter water expands, decreases in density, and rises to transfer heat to other regions of the water, while colder water sinks to the bottom. This process keeps repeating. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image shows a cross-section of a pot or kettle placed on a gas stove. Inside the pot, water is depicted as boiling, with circular arrows indicating the convection currents. Small bubbles are visible in the water, illustrating the boiling process. The pot itself is gray, with handles on the sides, and sits securely on a stove burner. The flame from the gas burner is blue and is depicted as providing heat to the bottom of the pot, causing the water to boil.

Take-Home Experiment: Convection Rolls in a Heated Pan

Take two small pots of water and use an eye dropper to place a drop of food coloring near the bottom of each. Leave one on a bench top and heat the other over a stovetop. Watch how the color spreads and how long it takes the color to reach the top. Watch how convective loops form.

Example 12.7

Calculating Heat Transfer by Convection: Convection of Air Through the Walls of a House

Most houses are not airtight: air goes in and out around doors and windows, through cracks and crevices, following wiring to switches and outlets, and so on. The air in a typical house is completely replaced in less than an hour. Suppose that a moderately-sized house has inside dimensions [latex]12.0 \text{m} \times 18.0 \text{m} \times 3.00 \text{m}[/latex]

high, and that all air is replaced in 30.0 min. Calculate the heat transfer per unit time in watts needed to warm the incoming cold air by [latex]\text{10} . 0º \text{C}[/latex], thus replacing the heat transferred by convection alone.

Strategy

Heat is used to raise the temperature of air so that [latex]Q = \text{mc} \Delta T[/latex]. The rate of heat transfer is then [latex]Q / t[/latex], where [latex]t[/latex] is the time for air turnover. We are given that [latex]\Delta T[/latex]

is [latex]\text{10} . 0º \text{C}[/latex], but we must still find values for the mass of air and its specific heat before we can calculate [latex]Q[/latex]. The specific heat of air is a weighted average of the specific heats of nitrogen and oxygen, which gives [latex]c = c_{\text{p}} \cong \text{1000} \textrm{ }\text{J}/\text{kg} ⋅º \text{C}[/latex] from Table 12.1 (note that the specific heat at constant pressure must be used for this process).

Solution

- Determine the mass of air from its density and the given volume of the house. The density is given from the density [latex]\rho[/latex] and the volume

[latex]\begin{align*}m &= \rho\text{V} \\&= \left(1 . \text{29} \text{kg}/\text{m}^{3}\right) \left(\text{12} . 0 \text{m} \times \text{18} . 0 \text{m} \times 3.00 \text{m}\right) \\&= \text{836} \text{kg}.\end{align*}[/latex]

12.37 - Calculate the heat transferred from the change in air temperature: [latex]Q = \text{mc} \Delta T[/latex] so that

[latex]\begin{align*}Q &= \left(\text{836} \text{kg}\right) \left(\text{1000 J}/\text{kg} ⋅º \text{C}\right) \left(\text{10}.\text{0}º \text{C}\right) \text{ }\\&=\text{ 8} . \text{36} \times \text{10}^{6} \text{J}.\end{align*}[/latex]

12.38 - Calculate the heat transfer from the heat [latex]Q[/latex] and the turnover time [latex]t[/latex]. Since air is turned over in [latex]t = 0 . 500 \text{h} = \text{1800} \text{s}[/latex], the heat transferred per unit time is

[latex]\frac{Q}{t} = \frac{8 . \text{36} \times \text{10}^{6} \text{J}}{\text{1800}\textrm{ } \text{s}} = 4 . 64 \text{kW}.[/latex]

12.39

Discussion

This rate of heat transfer is equal to the power consumed by about forty-six 100-W light bulbs. Newly constructed homes are designed for a turnover time of 2 hours or more, rather than 30 minutes for the house of this example. Weather stripping, caulking, and improved window seals are commonly employed. More extreme measures are sometimes taken in very cold (or hot) climates to achieve a tight standard of more than 6 hours for one air turnover. Still longer turnover times are unhealthy, because a minimum amount of fresh air is necessary to supply oxygen for breathing and to dilute household pollutants. The term used for the process by which outside air leaks into the house from cracks around windows, doors, and the foundation is called “air infiltration.”

A cold wind is much more chilling than still cold air, because convection combines with conduction in the body to increase the rate at which energy is transferred away from the body. The table below gives approximate wind-chill factors, which are the temperatures of still air that produce the same rate of cooling as air of a given temperature and speed. Wind-chill factors are a dramatic reminder of convection’s ability to transfer heat faster than conduction. For example, a 15.0 m/s wind at [latex]0º \text{C}[/latex] has the chilling equivalent of still air at about [latex]- \text{18}º \text{C}[/latex].

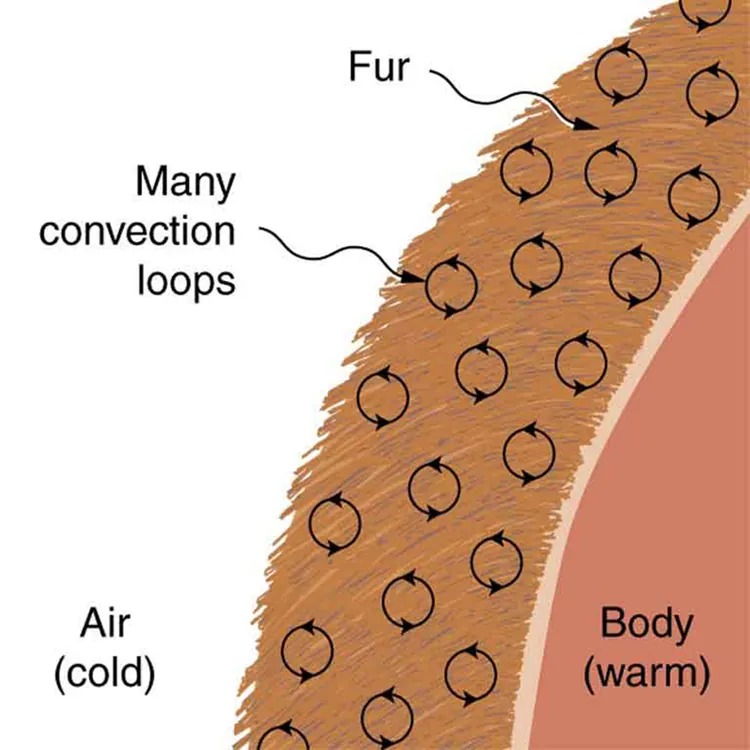

Figure 12.19 Fur is filled with air, breaking it up into many small pockets. Convection is very slow here, because the loops are so small. The low conductivity of air makes fur a very good lightweight insulator. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image is a diagram illustrating the concept of heat retention through fur, depicting a cross-sectional view. On the right side, there is a labeled section representing a “Body” which is described as “warm.” A layer of “Fur” is shown covering the body, with arrows within the fur indicating “Many convection loops.” These loops are depicted as circular arrows showing the flow of heat. The left side of the image shows “Air” which is labeled as “cold.” The diagram suggests that the fur and convection loops help in retaining the body’s warmth by minimizing the exposure to the cold air outside.

Some interesting phenomena happen when convection is accompanied by a phase change. It allows us to cool off by sweating, even if the temperature of the surrounding air exceeds body temperature. Heat from the skin is required for sweat to evaporate from the skin, but without air flow, the air becomes saturated and evaporation stops. Air flow caused by convection replaces the saturated air by dry air and evaporation continues.

Example 12.8

Calculate the Flow of Mass during Convection: Sweat-Heat Transfer away from the Body

The average person produces heat at the rate of about 120 W when at rest. At what rate must water evaporate from the body to get rid of all this energy? (This evaporation might occur when a person is sitting in the shade and surrounding temperatures are the same as skin temperature, eliminating heat transfer by other methods.)

Strategy

Energy is needed for a phase change ([latex]Q = \text{mL}_{\text{v}}[/latex]). Thus, the energy loss per unit time is

[latex]\frac{Q}{t} = \frac{\text{mL}_{\text{v}}}{t} = \text{120 }\textrm{ }\text{W} = \text{120 J}/\text{s}.[/latex]

We divide both sides of the equation by [latex]L_{\text{v}}[/latex] to find that the mass evaporated per unit time is

[latex]\frac{m}{t} = \frac{\text{120} \textrm{ }\text{J}/\text{s}}{L_{\text{v}}} .[/latex]

Solution

(1) Insert the value of the latent heat from Table 12.2, [latex]L_{\text{v}} = \text{2430} \textrm{ }\text{kJ}/\text{kg} = \text{2430} \textrm{ }\text{J}/\text{g}[/latex]. This yields

[latex]\frac{m}{t} = \frac{\text{120} \textrm{ }\text{J}/\text{s}}{\text{2430} \textrm{ }\text{J}/\text{g}} = 0 . \text{0494} \textrm{ }\text{g}/\text{s} = 2 . \text{96} \textrm{ }\text{g}/\text{min}.[/latex]

Discussion

Evaporating about 3 g/min seems reasonable. This would be about 180 g (about 7 oz) per hour. If the air is very dry, the sweat may evaporate without even being noticed. A significant amount of evaporation also takes place in the lungs and breathing passages.

Another important example of the combination of phase change and convection occurs when water evaporates from the oceans. Heat is removed from the ocean when water evaporates. If the water vapor condenses in liquid droplets as clouds form, heat is released in the atmosphere. Thus, there is an overall transfer of heat from the ocean to the atmosphere. This process is the driving power behind thunderheads, those great cumulus clouds that rise as much as 20.0 km into the stratosphere. Water vapor carried in by convection condenses, releasing tremendous amounts of energy. This energy causes the air to expand and rise, where it is colder. More condensation occurs in these colder regions, which in turn drives the cloud even higher. Such a mechanism is called positive feedback, since the process reinforces and accelerates itself. These systems sometimes produce violent storms, with lightning and hail, and constitute the mechanism driving hurricanes.

Figure 12.20 Cumulus clouds are caused by water vapor that rises because of convection. The rise of clouds is driven by a positive feedback mechanism. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Figure 12.21 Convection accompanied by a phase change releases the energy needed to drive this thunderhead into the stratosphere. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Figure 12.22 The phase change that occurs when this iceberg melts involves tremendous heat transfer. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

The movement of icebergs is another example of convection accompanied by a phase change. Suppose an iceberg drifts from Greenland into warmer Atlantic waters. Heat is removed from the warm ocean water when the ice melts and heat is released to the land mass when the iceberg forms on Greenland.

Check Your Understanding

Explain why using a fan in the summer feels refreshing!

Click for Solution

Solution

Using a fan increases the flow of air: warm air near your body is replaced by cooler air from elsewhere. Convection increases the rate of heat transfer so that moving air “feels” cooler than still air.