10.2 Bernoulli’s Equation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the terms in Bernoulli’s equation.

- Explain how Bernoulli’s equation is related to conservation of energy.

- Explain how to derive Bernoulli’s principle from Bernoulli’s equation.

- Calculate with Bernoulli’s principle.

- List some applications of Bernoulli’s principle.

When a fluid flows into a narrower channel, its speed increases. That means its kinetic energy also increases. Where does that change in kinetic energy come from? The increased kinetic energy comes from the net work done on the fluid to push it into the channel and the work done on the fluid by the gravitational force, if the fluid changes vertical position. Recall the work-energy theorem,

[latex]W_{\text{net}} = \frac{1}{2} \text{mv}^{2} - \frac{1}{2} \text{mv}_{0}^{2} .[/latex]

There is a pressure difference when the channel narrows. This pressure difference results in a net force on the fluid: recall that pressure times area equals force. The net work done increases the fluid’s kinetic energy. As a result, the pressure will drop in a rapidly-moving fluid, whether or not the fluid is confined to a tube.

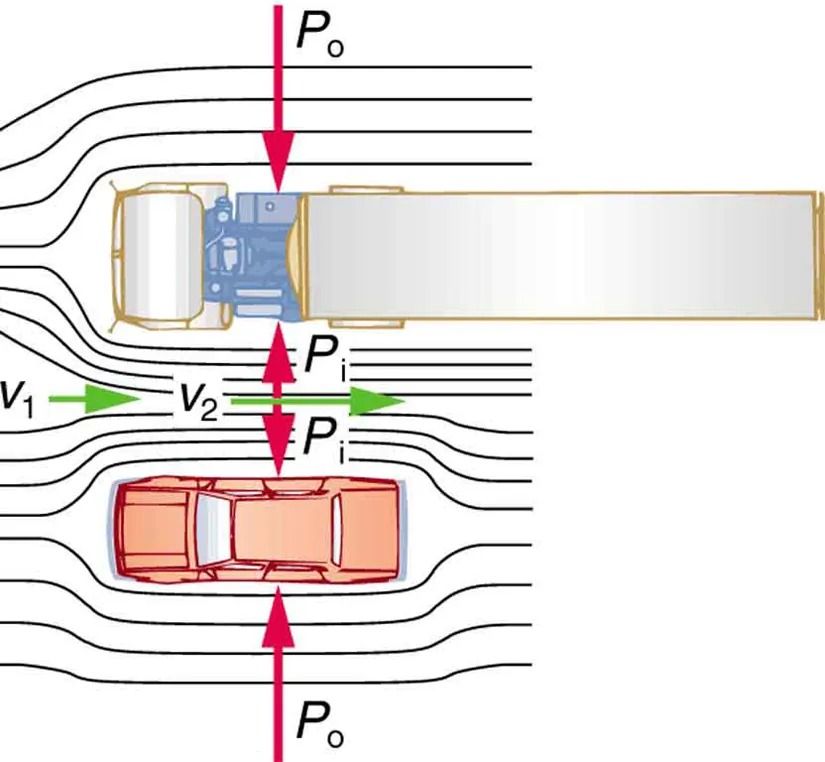

There are a number of common examples of pressure dropping in rapidly-moving fluids. Shower curtains have a disagreeable habit of bulging into the shower stall when the shower is on. The high-velocity stream of water and air creates a region of lower pressure inside the shower, and standard atmospheric pressure on the other side. The pressure difference results in a net force inward pushing the curtain in. You may also have noticed that when passing a truck on the highway, your car tends to veer toward it. The reason is the same—the high velocity of the air between the car and the truck creates a region of lower pressure, and the vehicles are pushed together by greater pressure on the outside. (See Figure 10.4.) This effect was observed as far back as the mid-1800s, when it was found that trains passing in opposite directions tipped precariously toward one another.

Figure 10.4 An overhead view of a car passing a truck on a highway. Air passing between the vehicles flows in a narrower channel and must increase its speed ([latex]v_{2}[/latex] is greater than [latex]v_{1}[/latex]), causing the pressure between them to drop ([latex]P_{\text{i}}[/latex] is less than [latex]P_{\text{o}}[/latex]). Greater pressure on the outside pushes the car and truck together. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image illustrates air flow and pressure around a large truck and a smaller car positioned parallel to each other. Streamlines represent the air flow:

– The truck is situated at the top, seen from a top-down view, with the trailer extending to the right.

– Below the truck, there’s a car, also viewed from above.

– Streamlines curve around both vehicles, indicating aerodynamic flow.

– Arrows labeled with “Po” point vertically outwards from both the truck and car, representing the external pressure.

– A pair of arrows, labeled “Pi” and pointing towards each other, indicate the internal pressure between the vehicles.

– Green arrows labeled “v1” and “v2” point horizontally, representing velocity vectors; “v1” is on the left, directed towards the gap between the vehicles, and “v2” is inside the gap between the truck and car, pointing towards the car.

The diagram visually conveys the principle of air pressure and velocity changes between two moving vehicles.

Making Connections: Take-Home Investigation with a Sheet of Paper

Hold the short edge of a sheet of paper parallel to your mouth with one hand on each side of your mouth. The page should slant downward over your hands. Blow over the top of the page. Describe what happens and explain the reason for this behavior.

Bernoulli’s Equation

The relationship between pressure and velocity in fluids is described quantitatively by Bernoulli’s equation, named after its discoverer, the Swiss scientist Daniel Bernoulli (1700–1782). Bernoulli’s equation states that for an incompressible, frictionless fluid, the following sum is constant:

[latex]P + \frac{1}{2} ρv^{2} + \rho \text{gh} = \text{constant},[/latex]

where [latex]P[/latex] is the absolute pressure, [latex]\rho[/latex] is the fluid density, [latex]v[/latex] is the velocity of the fluid, [latex]h[/latex] is the height above some reference point, and [latex]g[/latex] is the acceleration due to gravity. If we follow a small volume of fluid along its path, various quantities in the sum may change, but the total remains constant. Let the subscripts 1 and 2 refer to any two points along the path that the bit of fluid follows; Bernoulli’s equation becomes

[latex]P_{1} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{1}^{2} + \rho gh_{1} = P_{2} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2} + \rho gh_{2} .[/latex]

Bernoulli’s equation is a form of the conservation of energy principle. Note that the second and third terms are the kinetic and potential energy with [latex]m[/latex] replaced by [latex]\rho[/latex]. In fact, each term in the equation has units of energy per unit volume. We can prove this for the second term by substituting [latex]\rho = m / V[/latex] into it and gathering terms:

[latex]\frac{1}{2} ρv^{2} = \frac{\frac{1}{2} \text{mv}^{2}}{V} = \frac{\text{KE}}{V} .[/latex]

So [latex]\frac{1}{2} ρv^{2}[/latex] is the kinetic energy per unit volume. Making the same substitution into the third term in the equation, we find

[latex]\rho gh = \frac{mgh}{V} = \frac{\text{PE}_{\text{g}}}{V} ,[/latex]

so [latex]\rho \text{gh}[/latex] is the gravitational potential energy per unit volume. Note that pressure [latex]P[/latex] has units of energy per unit volume, too. Since [latex]P = F / A[/latex], its units are [latex]\text{N}/\text{m}^{2}[/latex]. If we multiply these by m/m, we obtain [latex]\text{N} \cdot \text{m}/\text{m}^{3} = \text{J}/\text{m}^{3}[/latex], or energy per unit volume. Bernoulli’s equation is, in fact, just a convenient statement of conservation of energy for an incompressible fluid in the absence of friction.

Making Connections: Conservation of Energy

Conservation of energy applied to fluid flow produces Bernoulli’s equation. The net work done by the fluid’s pressure results in changes in the fluid’s [latex]\text{KE}[/latex] and [latex]\text{PE}_{\text{g}}[/latex] per unit volume. If other forms of energy are involved in fluid flow, Bernoulli’s equation can be modified to take these forms into account. Such forms of energy include thermal energy dissipated because of fluid viscosity.

The general form of Bernoulli’s equation has three terms in it, and it is broadly applicable. To understand it better, we will look at a number of specific situations that simplify and illustrate its use and meaning.

Bernoulli’s Equation for Static Fluids

Let us first consider the very simple situation where the fluid is static—that is, [latex]v_{1} = v_{2} = 0[/latex]. Bernoulli’s equation in that case is

[latex]P_{1} + \rho gh_{1} = P_{2} + \rho gh_{2} .[/latex]

We can further simplify the equation by taking [latex]h_{2} = 0[/latex] (we can always choose some height to be zero, just as we often have done for other situations involving the gravitational force, and take all other heights to be relative to this). In that case, we get

[latex]P_{2} = P_{1} + \rho gh_{1} .[/latex]

This equation tells us that, in static fluids, pressure increases with depth. As we go from point 1 to point 2 in the fluid, the depth increases by [latex]h_{1}[/latex], and consequently, [latex]P_{2}[/latex] is greater than [latex]P_{1}[/latex] by an amount [latex]\rho gh_{1}[/latex]. In the very simplest case, [latex]P_{1}[/latex] is zero at the top of the fluid, and we get the familiar relationship [latex]P = \rho gh[/latex]. (Recall that [latex]P = ρgh[/latex] and [latex]\Delta \text{PE}_{\text{g}} = \text{mgh} .[/latex]) Bernoulli’s equation includes the fact that the pressure due to the weight of a fluid is [latex]\rho \text{gh}[/latex]. Although we introduce Bernoulli’s equation for fluid flow, it includes much of what we studied for static fluids in the preceding chapter.

Bernoulli’s Principle—Bernoulli’s Equation at Constant Depth

Another important situation is one in which the fluid moves but its depth is constant—that is, [latex]h_{1} = h_{2}[/latex]. Under that condition, Bernoulli’s equation becomes

[latex]P_{1} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{1}^{2} = P_{2} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2} .[/latex]

Situations in which fluid flows at a constant depth are so important that this equation is often called Bernoulli’s principle. It is Bernoulli’s equation for fluids at constant depth. (Note again that this applies to a small volume of fluid as we follow it along its path.) As we have just discussed, pressure drops as speed increases in a moving fluid. We can see this from Bernoulli’s principle. For example, if [latex]v_{2}[/latex] is greater than [latex]v_{1}[/latex] in the equation, then [latex]P_{2}[/latex] must be less than [latex]P_{1}[/latex] for the equality to hold.

Example 10.4

Calculating Pressure: Pressure Drops as a Fluid Speeds Up

In Example 10.2, we found that the speed of water in a hose increased from 1.96 m/s to 25.5 m/s going from the hose to the nozzle. Calculate the pressure in the hose, given that the absolute pressure in the nozzle is [latex]1 . \text{01} \times \text{10}^{5} \text{N}/\text{m}^{2}[/latex] (atmospheric, as it must be) and assuming level, frictionless flow.

Strategy

Level flow means constant depth, so Bernoulli’s principle applies. We use the subscript 1 for values in the hose and 2 for those in the nozzle. We are thus asked to find [latex]P_{1}[/latex].

Solution

Solving Bernoulli’s principle for [latex]P_{1}[/latex] yields

[latex]{\small P_{1} = P_{2} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2} - \frac{1}{2} ρv_{1}^{2} = P_{2} + \frac{1}{2} \rho \left(\right. v_{2}^{2} - v_{1}^{2} \left.\right) .}[/latex]

Substituting known values,

[latex]{\small\begin{eqnarray*}P_{1} & = & 1 . \text{01} \times \text{10}^{5} \text{ N}/\text{m}^{2} \\ & & + \frac{1}{2} \left(\right. \text{10}^{3} \text{ kg}/\text{m}^{3} \left.\right) \left[\left(\right. \text{25}.\text{5 m}/\text{s} \left.\right)^{2} - \left(\right. \text{1}.\text{96 m}/\text{s} \left.\right)^{2}\right] \\ & = & 4.24 \times \text{10}^{5} \text{ N}/\text{m}^{2} .\end{eqnarray*}}[/latex]

Discussion

This absolute pressure in the hose is greater than in the nozzle, as expected since [latex]v[/latex] is greater in the nozzle. The pressure [latex]P_{2}[/latex] in the nozzle must be atmospheric since it emerges into the atmosphere without other changes in conditions.

Applications of Bernoulli’s Principle

There are a number of devices and situations in which fluid flows at a constant height and, thus, can be analyzed with Bernoulli’s principle.

Entrainment

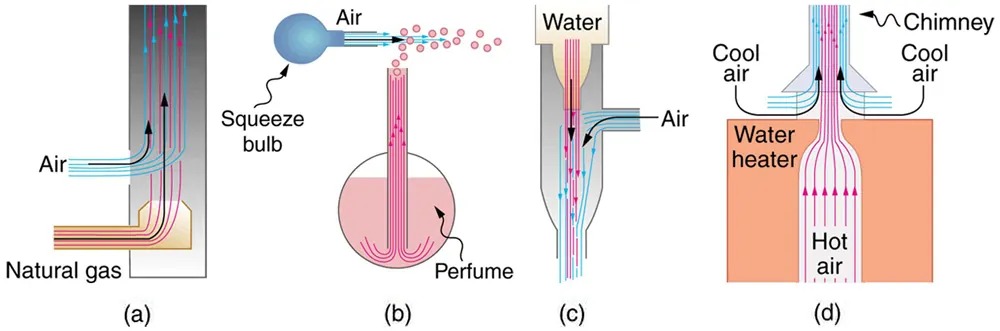

People have long put the Bernoulli principle to work by using reduced pressure in high-velocity fluids to move things about. With a higher pressure on the outside, the high-velocity fluid forces other fluids into the stream. This process is called entrainment. Entrainment devices have been in use since ancient times, particularly as pumps to raise water small heights, as in draining swamps, fields, or other low-lying areas. Some other devices that use the concept of entrainment are shown in Figure 10.5.

Figure 10.5 Examples of entrainment devices that use increased fluid speed to create low pressures, which then entrain one fluid into another. (a) A Bunsen burner uses an adjustable gas nozzle, entraining air for proper combustion. (b) An atomizer uses a squeeze bulb to create a jet of air that entrains drops of perfume. Paint sprayers and carburetors use very similar techniques to move their respective liquids. (c) A common aspirator uses a high-speed stream of water to create a region of lower pressure. Aspirators may be used as suction pumps in dental and surgical situations or for draining a flooded basement or producing a reduced pressure in a vessel. (d) The chimney of a water heater is designed to entrain air into the pipe leading through the ceiling. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image contains four diagrams labeled (a) to (d) that illustrate different examples of air and fluid flow dynamics:

1. Diagram (a):

– Displays a vertical tube with natural gas entering from the bottom.

– Air flows in from the sides, mixing with the natural gas and moving upwards.

2. Diagram (b):

– Features a squeeze bulb on the left which forces air through a vertical tube.

– Air carries perfume from a container upwards, dispersing it into the air.

3. Diagram (c):

– Shows a setup with water at the base and a vertical tube.

– Air flows in from the sides, mixes with the water, and moves upwards through the tube.

4. Diagram (d):

– Presents a water heater with hot air rising through a chimney in the center.

– Cool air enters from the sides, mixes with the hot air, and flows upwards through the chimney.

Wings and Sails

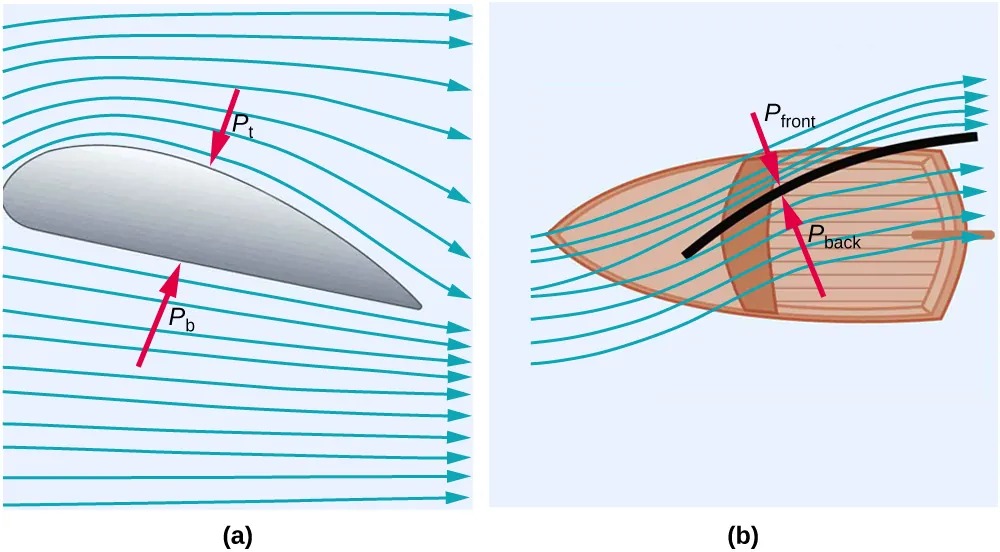

The airplane wing is a beautiful example of Bernoulli’s principle in action. Figure 10.6(a) shows the characteristic shape of a wing. The wing is tilted upward at a small angle and the upper surface is longer, causing air to flow faster over it. The pressure on top of the wing is therefore reduced, creating a net upward force or lift. (Wings can also gain lift by pushing air downward, utilizing the conservation of momentum principle. The deflected air molecules result in an upward force on the wing — Newton’s third law.) Sails also have the characteristic shape of a wing. (See Figure 10.6(b).) The pressure on the front side of the sail, [latex]P_{\text{front}}[/latex], is lower than the pressure on the back of the sail, [latex]P_{\text{back}}[/latex]. This results in a forward force and even allows you to sail into the wind.

Making Connections: Take-Home Investigation with Two Strips of Paper

For a good illustration of Bernoulli’s principle, make two strips of paper, each about 15 cm long and 4 cm wide. Hold the small end of one strip up to your lips and let it drape over your finger. Blow across the paper. What happens? Now hold two strips of paper up to your lips, separated by your fingers. Blow between the strips. What happens?

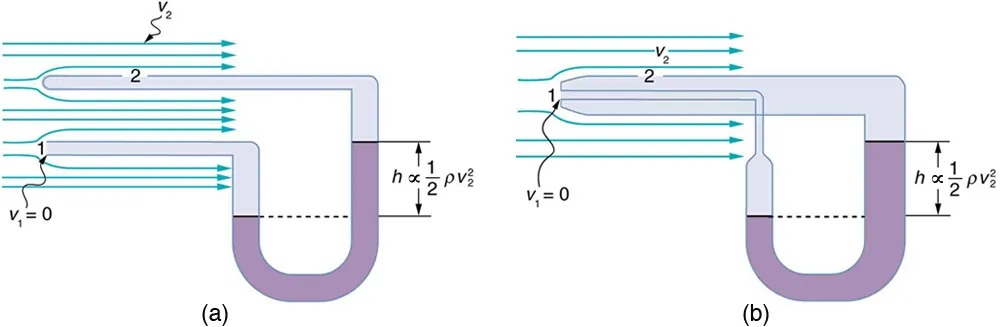

Velocity measurement

Figure 10.7 shows two devices that measure fluid velocity based on Bernoulli’s principle. The manometer in Figure 10.7(a) is connected to two tubes that are small enough not to appreciably disturb the flow. The tube facing the oncoming fluid creates a dead spot having zero velocity ([latex]v_{1} = 0[/latex]) in front of it, while fluid passing the other tube has velocity [latex]v_{2}[/latex]. This means that Bernoulli’s principle as stated in [latex]P_{1} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{1}^{2} = P_{2} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2}[/latex] becomes

[latex]P_{1} = P_{2} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2} .[/latex]

Figure 10.6 (a) The Bernoulli principle helps explain lift generated by a wing. (b) Sails use the same technique to generate part of their thrust. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image consists of two side-by-side diagrams labeled as (a) and (b).

Diagram (a):

– It shows a cross-sectional view of an airfoil, which is an aerodynamic shape similar to that of an airplane wing.

– Blue lines with arrows around the airfoil indicate the flow of air. The arrows show the direction of airflow.

– Two red arrows labeled as “Pt” and “Pb” indicate pressures on the top and bottom surfaces of the airfoil, respectively.

Diagram (b):

– It depicts a rowboat viewed from above, illustrating the effect of airflow on a curved sail.

– Blue lines with arrows suggest the direction and flow of air over the curved sail.

– Two red arrows labeled as “Pfront” and “Pback” indicate the pressures at the front and back of the sail.

Thus pressure [latex]P_{2}[/latex] over the second opening is reduced by [latex]\frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2}[/latex], and so the fluid in the manometer rises by [latex]h[/latex] on the side connected to the second opening, where

[latex]h \propto \frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2} .[/latex]

(Recall that the symbol [latex]∝[/latex] means “proportional to.”) Solving for [latex]v_{2}[/latex], we see that

[latex]v_{2} \propto \sqrt{h} .[/latex]

Figure 10.7(b) shows a version of this device that is in common use for measuring various fluid velocities; such devices are frequently used as air speed indicators in aircraft.

Figure 10.7 Measurement of fluid speed based on Bernoulli’s principle. (a) A manometer is connected to two tubes that are close together and small enough not to disturb the flow. Tube 1 is open at the end facing the flow. A dead spot having zero speed is created there. Tube 2 has an opening on the side, and so the fluid has a speed [latex]v[/latex] across the opening; thus, pressure there drops. The difference in pressure at the manometer is [latex]\frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2}[/latex], and so [latex]h[/latex] is proportional to [latex]\frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2}[/latex]. (b) This type of velocity measuring device is a Prandtl tube, also known as a pitot tube. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image consists of two diagrams, labeled (a) and (b), illustrating fluid flow through pipes with a U-tube manometer.

Diagram (a):

– Depicts a pipe with two sections labeled 1 and 2.

– Section 1 is horizontal, and section 2 curves downward into the U-tube manometer.

– Fluid enters section 1 with velocity \( v_1 = 0 \) and exits section 2 with velocity \( v_2 \).

– Streamlines are shown with arrows indicating the direction of flow.

– The U-tube manometer is half-filled with a liquid, with one side of the manometer aligned with the pipe outlet.

– The height difference \( h \) in the manometer fluid level is indicated to be proportional to \( \frac{1}{2} \rho v_2^2 \), where \( \rho \) is the fluid density.

Diagram (b):

– Illustrates a similar scenario to diagram (a).

– The pipe configuration is slightly different, with section 1 initially curving upwards before going horizontal.

– Section 2 exits horizontally into the U-tube manometer.

– The manometer setup and height difference \( h \) are shown similarly to diagram (a), with the same proportional relationship to \( \frac{1}{2} \rho v_2^2 \).

– Streamlines indicate the flow direction with arrows.

These diagrams demonstrate the principle that the height difference in the manometer is related to the velocity of the fluid in the pipe, illustrating Bernoulli’s principle in action.