10.3 The Most General Applications of Bernoulli’s Equation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Calculate using Torricelli’s theorem.

- Calculate power in fluid flow.

Torricelli’s Theorem

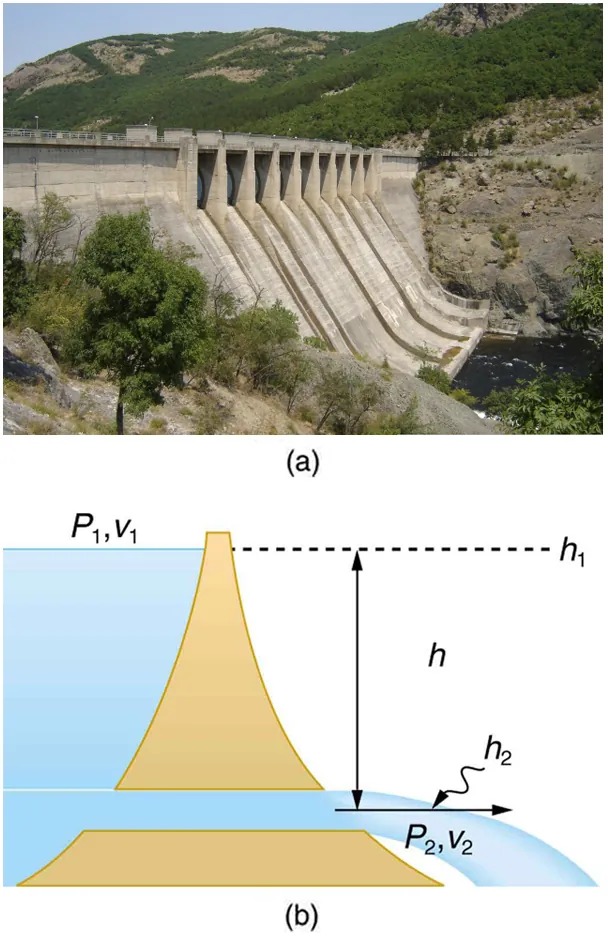

Figure 10.8 shows water gushing from a large tube through a dam. What is its speed as it emerges? Interestingly, if resistance is negligible, the speed is just what it would be if the water fell a distance [latex]h[/latex] from the surface of the reservoir; the water’s speed is independent of the size of the opening. Let us check this out. Bernoulli’s equation must be used since the depth is not constant. We consider water flowing from the surface (point 1) to the tube’s outlet (point 2). Bernoulli’s equation as stated in previously is

[latex]P_{1} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{1}^{2} + \rho \text{gh}_{1} = P_{2} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2} + \rho \text{gh}_{2} .[/latex]

Both [latex]P_{1}[/latex] and [latex]P_{2}[/latex] equal atmospheric pressure ([latex]P_{1}[/latex] is atmospheric pressure because it is the pressure at the top of the reservoir. [latex]P_{2}[/latex] must be atmospheric pressure, since the emerging water is surrounded by the atmosphere and cannot have a pressure different from atmospheric pressure.) and subtract out of the equation, leaving

[latex]\frac{1}{2} ρv_{1}^{2} + \rho \text{gh}_{1} = \frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2} + \rho \text{gh}_{2} .[/latex]

Solving this equation for [latex]v_{2}^{2}[/latex], noting that the density [latex]\rho[/latex] cancels (because the fluid is incompressible), yields

[latex]v_{2}^{2} = v_{1}^{2} + 2 g \left(\right. h_{1} - h_{2} \left.\right) .[/latex]

We let [latex]h = h_{1} - h_{2}[/latex]; the equation then becomes

[latex]v_{2}^{2} = v_{1}^{2} + 2 \text{gh}[/latex]

where [latex]h[/latex] is the height dropped by the water. This is simply a kinematic equation for any object falling a distance [latex]h[/latex] with negligible resistance. In fluids, this last equation is called Torricelli’s theorem. Note that the result is independent of the velocity’s direction, just as we found when applying conservation of energy to falling objects.

Figure 10.8 (a) Water gushes from the base of the Studen Kladenetz dam in Bulgaria. (credit: Kiril Kapustin; http://www.ImagesFromBulgaria.com) (b) In the absence of significant resistance, water flows from the reservoir with the same speed it would have if it fell the distance [latex]h[/latex] without friction. This is an example of Torricelli’s theorem. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image consists of two parts labeled (a) and (b).

(a) This is a photograph of a large dam situated in a mountainous area. The dam is made of concrete and features several spillways, which allow water to flow through. The surrounding landscape includes green hills and trees, and some rocky outcroppings are visible in the background. There is a body of water behind the dam, and the foreground features vegetation and trees.

(b) This is a schematic diagram illustrating the flow of water over a dam. It shows two water levels with corresponding pressures and velocities, labeled as P1, V1 at the higher level and P2, V2 at the lower level. The diagram includes two heights: h representing the total height of the dam, h1 indicating the water level difference from the top to the surface, and h2 relating to the drop past the dam. The diagram uses arrows and labels to convey the changes in pressure and flow velocity as water moves from higher to lower levels.

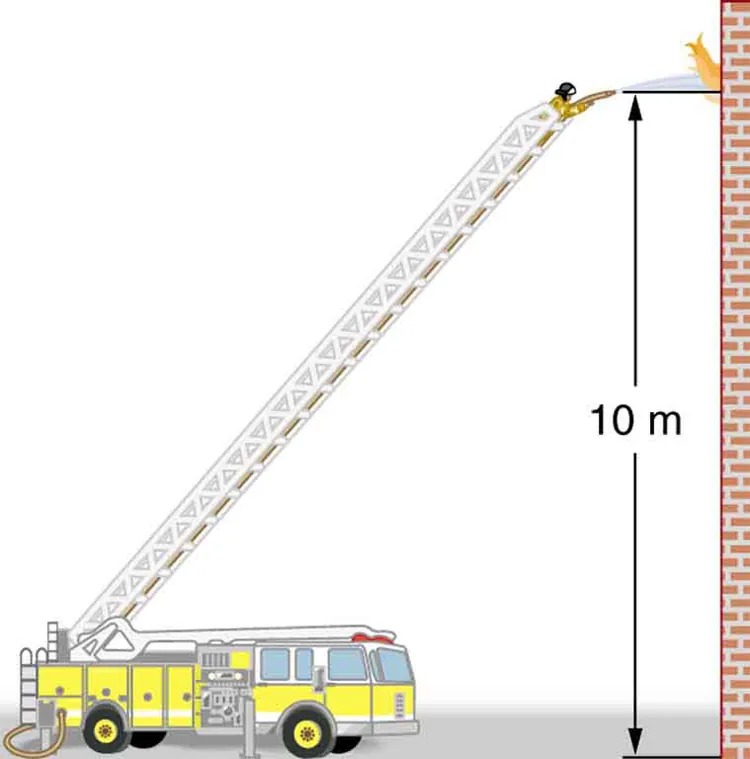

Figure 10.9 Pressure in the nozzle of this fire hose is less than at ground level for two reasons: the water has to go uphill to get to the nozzle, and speed increases in the nozzle. In spite of its lowered pressure, the water can exert a large force on anything it strikes, by virtue of its kinetic energy. Pressure in the water stream becomes equal to atmospheric pressure once it emerges into the air. Image from OpenStax College Physics 2e, CC-BY 4.0

Image Description

The image is a diagram featuring a yellow fire truck with an extended ladder. The ladder is reaching towards a brick building on the right side of the image. At the top of the ladder, a firefighter is leaning forward to rescue a cat that is perched on the edge of the building’s roof. There is a vertical measurement indicating a height of 10 meters from the ground to the top of the building where the cat is situated. The ladder forms an angled extension from the truck to the building.

All preceding applications of Bernoulli’s equation involved simplifying conditions, such as constant height or constant pressure. The next example is a more general application of Bernoulli’s equation in which pressure, velocity, and height all change. (See Figure 10.9.)

Example 10.5

Calculating Pressure: A Fire Hose Nozzle

Fire hoses used in major structure fires have inside diameters of 6.40 cm. Suppose such a hose carries a flow of 40.0 L/s starting at a gauge pressure of [latex]1 . \text{62} \times \text{10}^{6} \text{N}/\text{m}^{2}[/latex]. The hose goes 10.0 m up a ladder to a nozzle having an inside diameter of 3.00 cm. Assuming negligible resistance, what is the initial water pressure at the base of the hose?

Strategy

Here we must use Bernoulli’s equation to solve for the pressure, since depth is not constant.

Solution

Bernoulli’s equation states

[latex]P_{1} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{1}^{2} + \rho \text{gh}_{1} = P_{2} + \frac{1}{2} ρv_{2}^{2} + \rho \text{gh}_{2} ,[/latex]

where the subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the initial conditions at ground level and the final conditions inside the nozzle, respectively. We must first find the speeds [latex]v_{1}[/latex] and [latex]v_{2}[/latex]. Since [latex]Q = A_{1} v_{1}[/latex], we get

[latex]v_{1} = \frac{Q}{A_{1}} = \frac{\text{40} . 0 \times \text{10}^{- 3} \text{m}^{3} /\text{s}}{\pi \left(\right. 3 . \text{20} \times \text{10}^{- 2} \text{m} \left.\right)^{2}} = 12.434 \text{m}/\text{s} .[/latex]

Similarly, we find

[latex]v_{2} = \text{56}.\text{588 m}/\text{s} .[/latex]

(This rather large speed is helpful in reaching the fire.) Now, taking [latex]h_{1}[/latex] to be zero, we solve Bernoulli’s equation for [latex]P_{2}[/latex]:

[latex]P_{2} = P_{1} + \frac{1}{2} \rho \left(v_{1}^{2} - v_{2}^{2}\right) - \rho \text{gh}_{2} .[/latex]

In the proposed solution, [latex]P_{2} = 0[/latex], so

[latex]{\scriptsize\begin{align*}P_{1} – P_{2} &= P_{1} \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \left(\right. \text{1000} \text{kg}/\text{m}^{3} \left.\right) \left[\right. \left(\right. 12.434 \text{m}/\text{s} \left.\right)^{2} - \left(\right. 56.588 \text{m}/\text{s} \left.\right)^{2} \left]\right. \\ &\text{ }\;\;\;- \left(\right. \text{1000} \text{kg}/\text{m}^{3} \left.\right) \left(\right. 9.80 \text{m}/\text{s}^{2} \left.\right) \left(\right. 10.0 \text{m} \left.\right) \\ &\approx 1.62 \times \text{10}^{\text{6}} \text{N}/\text{m}^{2} .\end{align*}}[/latex]

Discussion

This value is a gauge pressure, since the initial pressure was given as a gauge pressure. Thus the nozzle pressure is very close to atmospheric pressure, as it must because the water exits into the atmosphere without changes in its conditions.

Power in Fluid Flow

Power is the rate at which work is done or energy in any form is used or supplied. To see the relationship of power to fluid flow, consider Bernoulli’s equation:

[latex]P + \frac{1}{2} ρv^{2} + \rho \text{gh} = \text{constant} .[/latex]

All three terms have units of energy per unit volume, as discussed in the previous section. Now, considering units, if we multiply energy per unit volume by flow rate (volume per unit time), we get units of power. That is, [latex]\left(\right. E / V \left.\right) \left(\right. V / t \left.\right) = E / t[/latex]. This means that if we multiply Bernoulli’s equation by flow rate [latex]Q[/latex], we get power. In equation form, this is

[latex]\left(P + \frac{1}{2} ρv^{2} + \rho \text{gh}\right) Q = \text{power} .[/latex]

Each term has a clear physical meaning. For example, [latex]\text{PQ}[/latex] is the power supplied to a fluid, perhaps by a pump, to give it its pressure [latex]P[/latex]. Similarly, [latex]\frac{1}{2} ρv^{2} Q[/latex] is the power supplied to a fluid to give it its kinetic energy. And [latex]\rho \text{ghQ}[/latex] is the power going to gravitational potential energy.

Making Connections: Power

Power is defined as the rate of energy transferred, or [latex]E / t[/latex]. Fluid flow involves several types of power. Each type of power is identified with a specific type of energy being expended or changed in form.

Example 10.6

Calculating Power in a Moving Fluid

Suppose the fire hose in the previous example is fed by a pump that receives water through a hose with a 6.40-cm diameter coming from a hydrant with a pressure of [latex]0 . \text{700} \times \text{10}^{6} \text{N}/\text{m}^{2}[/latex]. What power does the pump supply to the water?

Strategy

Here we must consider energy forms as well as how they relate to fluid flow. Since the input and output hoses have the same diameters and are at the same height, the pump does not change the speed of the water nor its height, and so the water’s kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy are unchanged. That means the pump only supplies power to increase water pressure by [latex]0 . \text{92} \times \text{10}^{6} \text{N}/\text{m}^{2}[/latex] (from [latex]0.700 \times \text{10}^{6} \text{N}/\text{m}^{2}[/latex] to [latex]1.62 \times \text{10}^{6} \text{N}/\text{m}^{2}[/latex]).

Solution

As discussed above, the power associated with pressure is

[latex]{\small\begin{eqnarray*}\text{power} & = & \text{PQ} \\ & = & \left(\text{0}.\text{920} \times \text{10}^{6} \text{N}/\text{m}^{2}\right) \left(\text{40} . 0 \times \text{10}^{- 3} \text{m}^{3} /\text{s}\right) . \\ & = & 3 . \text{68} \times \text{10}^{4} \text{W} = \text{36} . 8 \text{kW} .\end{eqnarray*}}[/latex]

Discussion

Such a substantial amount of power requires a large pump, such as is found on some fire trucks. (This kilowatt value converts to about 50 hp.) The pump in this example increases only the water’s pressure. If a pump—such as the heart—directly increases velocity and height as well as pressure, we would have to calculate all three terms to find the power it supplies.