3.6 Whose Knowledge is Valued?

In this last section of Chapter 3, we return to the case study to consider two final elements of knowledge justice. Along with learning to answer questions like “What is knowledge?” and “Who is allowed to be knowledgeable?,” we want to uncover the values and beliefs people hold about knowledge, or their axiology.In other words, we want to investigate what and whose knowledge our discipline considers worth sharing and protecting.

For example, we live in a westernized culture where knowledge is often shared and preserved by writing it down. In Canadian school systems, teachers certainly pass on knowledge through story and voice, but there remains an unspoken belief that “real” knowledge lives in books, academic journal articles, and so on. Knowledge-sharing platforms like YouTube aren’t considered “real knowledge” and, in academic work, we’re often discouraged from citing lived experience, dreams, or land-based knowledge (Rowe, 2014). Similarly, western culture assumes that knowledge can be owned and sold by individuals, with rules like copyright law governing how knowledge is accessed, shared, and protected.

As we saw earlier in Chapter 3, such beliefs about knowledge stem from cultural epistemologies and are not universal. On their own, knowledge sources like books and journal articles aren’t harmful, but when they are used to discount, erase, or exploit other forms of knowledge, they contribute to epistemic injustice.

Watch the video below from librarian Jessie Loyer about Storytelling for a quick example.

@indigenouslibrarian in libraries, documentation = authority, and authority = whiteness, from Hannah Turner’s (2020) book Cataloging Culture

How is knowledge shared and cared for?

Part of practicing knowledge justice is learning to navigate dominant systems and work within and around them to find a range of voices and perspectives. But where are diverse voices able to speak and be heard? Answering this question helps us move outside the traditions of our discipline, or the edges of our epistemology.

We know we are expected to use academic sources in our disciplines, for example, but such sources do not always represent the knowledges of those holding diverse social identities. If we can’t find marginalized perspectives in the ‘evidence’ preferred by our disciplines, where might we find them? Where are these voices allowed to speak?

Watch the next video where your authors apply the Voices Flower to the knowledge sources we often encounter in the helping professions.

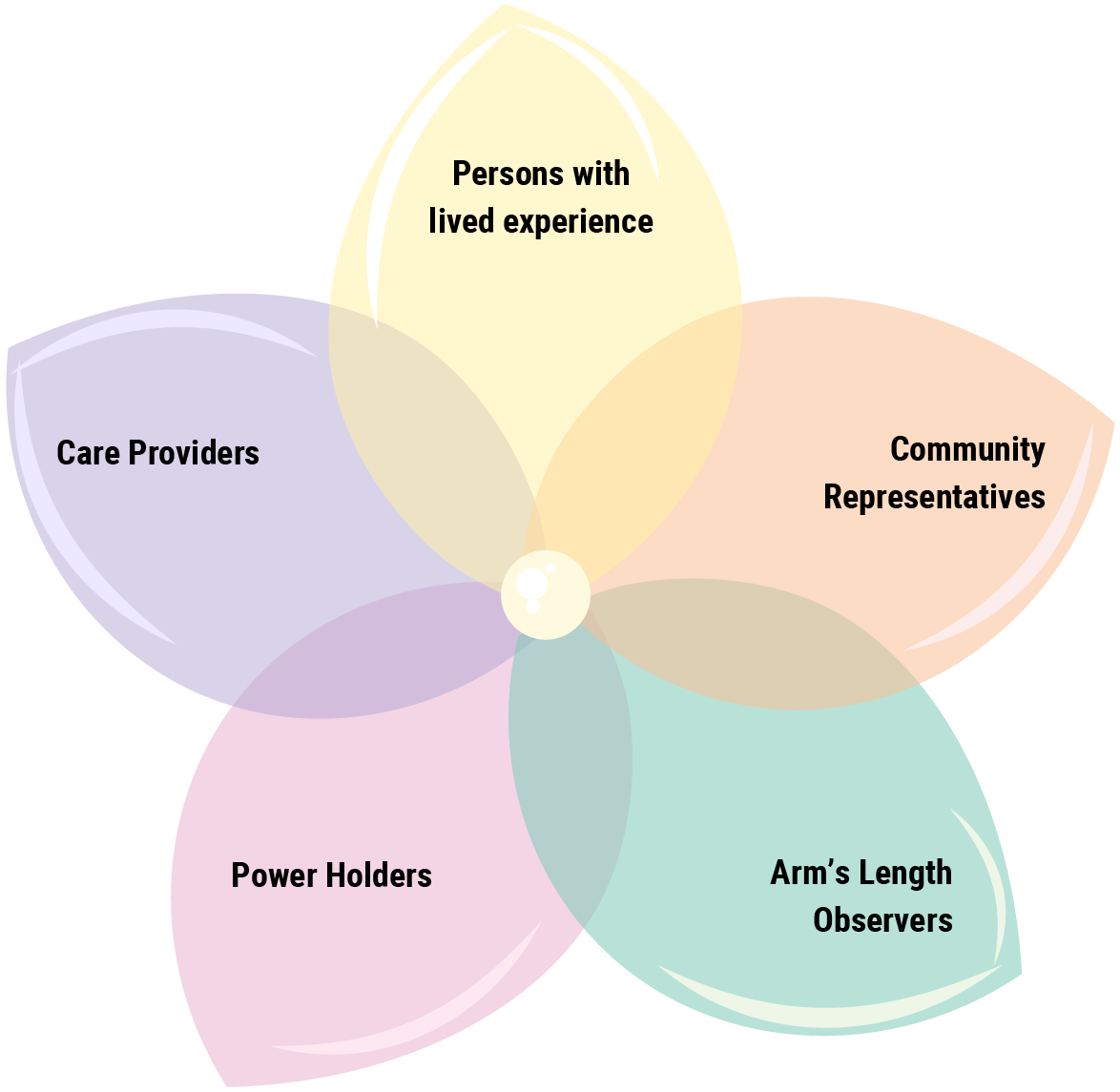

As we saw in the video, the Voices Flower represents the idea that knowledge is not only produced within or by a university. By naming Power Holders or Community Representatives, the Voices Flower recognizes that knowledge is produced and held outside the academic domain, such as economic, political, cultural, and family knowledges.

We also want to acknowledge that while tools like the Voices Flower can be useful, they are still produced within a westernized academic context. There are ways of knowing that fall beyond the scope of what a tool like this can do, since it does not capture domains like cultural, political, land-based, or ancestral knowledges. We can see, again, the importance of practicing Two-Eyed Seeing in partnership with knowledge justice.

Demonstrating Using Our Case Study

Now, let’s use the Voices Flower to explore where we might find diverse knowledges relevant to our case study. Refer back to the workbook to review the case study.

When we introduced the case study earlier in this chapter, we invited you to think about the case broadly. You may have identified several areas where support was required for the client, depending on your home discipline, lived experience, and future profession.

To give some examples: perhaps you considered the importance of supporting the client with infant feeding or safe sleep practices. Alternatively, you may be thinking about housing, supports for refugee families, or the wellness of the younger sister.

For the purposes of the demonstration below, we’ll use safe infant sleep practices as our primary focus. But as we demonstrate how to use the Voices Flower to identify diverse knowledges sources about safe sleep, think about how you might practice this strategy in your professional practice, including when addressing other facets of this case.

A branch of philosophy, studying the values and beliefs people hold.