12 Debriefing

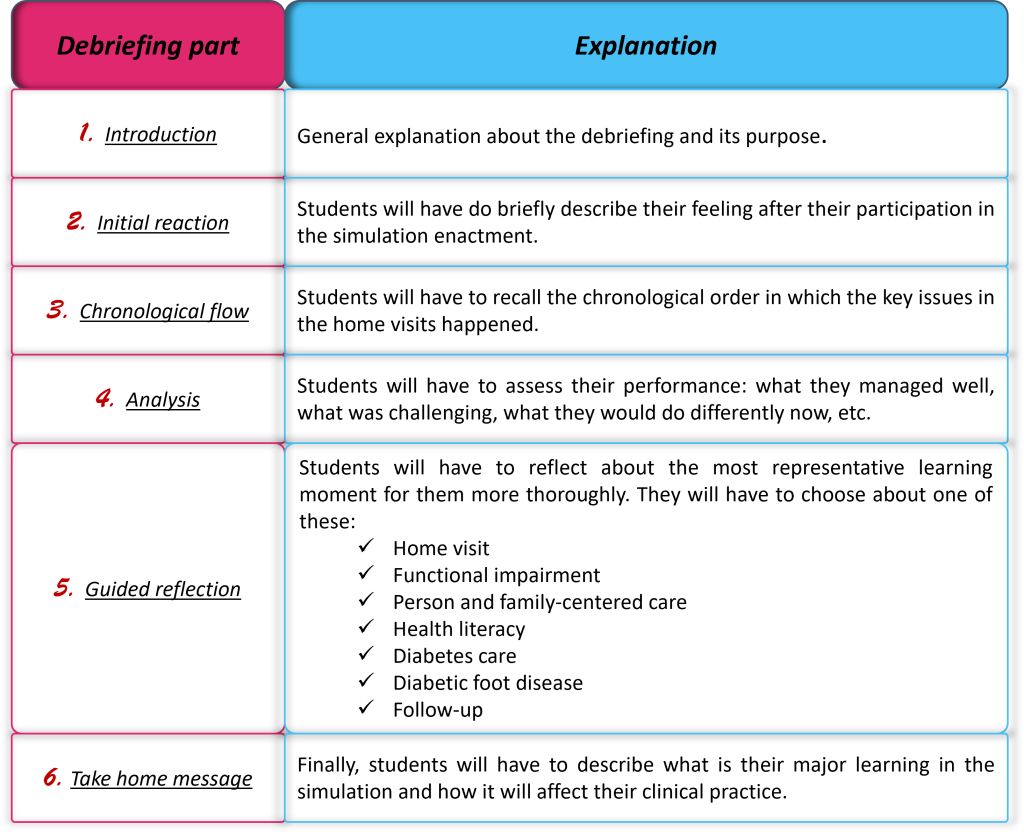

The main objective of the debriefing is that the students get to know, evaluate, refine and enhance the mental models that guide their behaviour in a professional environment and made them act in the way they did during the simulation (Zigmont et al., 2011b). To do so, this VGS is provided with an integrated self-debriefing, in which students can individually reflect, just after the enactment ends, guided through a cluster of questions specifically defined to promote students learning in the topic of the VGS. During this individual self-debriefing phase, students will have to write the answers to 10 open questions in the given order with the goal of expressing their initial reaction to the VGS, reconstructing the scenario, analysing issues, reflecting on their performance, and making connections to future clinical practice.

It will take students approximately 30 minutes to complete the questions, and they are encouraged to use their individual summary report, automatically created at the end of the enactment phase, as well as notes that they might have taken during class. Finally, students will be able to generate a report with their self-debriefing answers.

The self-debriefing its structured in 6 parts:

Nonetheless, facilitators should feel free to change the debriefing questions to better fit the learning needs of their students. As we have already explained, if facilitators embed the VGS into their LMS platform, they will be able to adapt the different parts of the simulation to the needs of their learners.

In addition to the self-debriefing included in the VGS Hello, you must be Flo!, there are other modalities in which the debriefing can be conducted, such as the collective group discussion during which students, guided by facilitators, analyse their performance (individually or as a group) (Zigmont et al., 2011a). This facilitator led debriefing promotes the exchange of opinions, discussion, learning from colleagues, etc. Therefore, both ways of debriefing present advantages and disadvantages, which has made some authors like Gantt et al. (2018), Lapum et al. (2019) and Verkuyl et al. (2020) to investigate about the better method of debriefing.

Our recommendation for this VGS, also supported by the research of Verkuyl et al. (2020), is to mix the individual self-debriefing with a group discussion, what allows to get profit from the positive elements of both debriefing ways. That implies to experience an immediate self-debrief just next to the end of the enactment phase (INACSL Standards Committee, 2016) so that the students can vividly remember the case and the decisions taken, experience a high degree of safety when reflecting about their experience in the simulation, reach a higher level of self-awareness about their learning needs, and have the possibility of writing down their reflections in a non-timely controlled environment. But also, a large group debriefing session in which learners, accompanied by their written reflection of the self-debriefing, will have the chance to exchange thoughts and discuss about them with colleagues and the facilitator.

More information about debriefing

More information about debriefing

Debriefing is an essential part of the VGS process. Although experience and practice are the basis of adults learning, Kolb’s experiential learning theory also tells us that, in order to form new knowledge, reflecting on the experience is needed to identify one’s knowledge gaps. Analysing values and assumptions and finally create new ideas and knowledge that can be transfer into other situations (Maestre & Rudolph, 2015). Therefore, debriefing plays a key role in VGS by promoting reflection about the experience, and, thus, the students learning (Aebersold, 2018; Hall & Tori, 2017; Verkuyl et al., 2020; Zigmont et al., 2011b). Students also highly value this debriefing process (Verkuyl et al., 2017), realising that it significantly increases their learning and understanding of their performance in the simulation and the contents and protocols used. Some authors go as far as to say that “the actual learning does not occur during the experience itself, but rather during the debriefing that follows” (Zigmont et al., 2011b, p. 49).

In case facilitators want to complement the self-debriefing integrated into the VGS with a synchronous group debriefing, these are some advises might help facilitators in performing a successful debriefing session (Verkuyl et al., 2018, 2022):

- Remind the learning objectives of the VGS and reorient learners to the specific outcomes that they will achieve in this session.

- Provide clear instructions about what is expected from the learners and if they will be graded or not.

- Inform the students about who will read their answers and what will be the purpose.

- Promote psychological safety and invite learners to engage in the discussions that might arise. This is especially important when debriefing in groups because, although when self-debriefing is more common to feel psychologically safe and provide authentic and honest responses, in group discussion that safety tends to decrease by the fear to be judged by your colleges or facilitator.

- When designing additional activities for debriefing, it is crucial to have a clear idea of the way in which they relate with the learning objectives of the VGS.

- Encourage students to use the individual report of their decisions obtained from their experience in the VGS. This will be useful to support the discussion based on their learning needs.

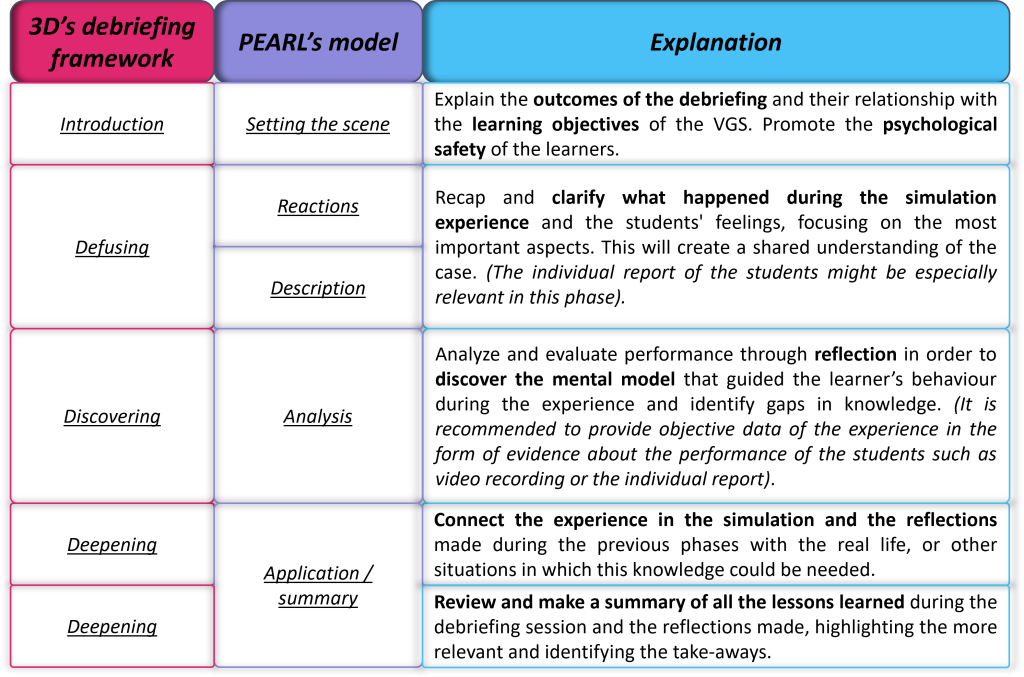

Also, it is highly recommended to follow some debriefing model, such as the 3D’s debriefing framework of Zigmont et al. (2011a) or the PEARL’s model of Bajaj et al. (2018), which provide a structure in which the debriefing session should be done to be as effective as possible. In the next table these models are combined and explained:

complementary resources

complementary resources

Along with offering a safe and supportive environment, the congruence with the learning objectives of the VGS, and the theoretically informed debrief questions, it is also crucial a competent facilitator who is familiar with the VGS for the debriefing session to succeed (INACSL Standards Committee, 2016). That is why we highly recommend the facilitator to check the following materials before the implementation of the debriefing with their students:

- INACSL Standards Committee (2016, December). INACSL standards of best practice: SimulationSM Debriefing. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 12(S), S21-S25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2016.09.008

- Zigmont, J., Kappus, L., & Sudikoff, S. (2011). The 3D model of debriefing: defusing, discovery, and deepening. Seminars in Perinatology, 35(2), 52-58. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2011.01.003.

- Bajaj, K., Meguerdichian, M., Thoma, B., Huang, S., Eppich, W., & Cheng, A. (2018). The PEARLS Healthcare Debriefing Tool. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 93(2), 336. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002035