The Role of Justice and Racism in Environmental Education

Introduction

Environmental inequity has a long history in Canada. Decades of research have repeatedly shown that environmental harms such as air pollution and toxic waste disproportionately affect neighbourhoods with greater percentages of low-income, Indigenous, Black and/or other racialized communities.[1]

The concepts of environmental equity and environmental justice have been attracting renewed attention on the national and international stage. The House of Commons in Canada is currently deliberating Bill C-266, (it passed a second reading but died automatically when a federal election was called in September 2021). If passed, it would require the development of a national strategy for advancing environmental justice and assessing, preventing, and addressing environmental racism.

Canada’s newly released National Adaptation Strategy identifies equity and environmental justice collectively as one of four guiding principles for designing and advancing climate adaptation strategies, and thus we ask that you integrate it into your climate and environment education programs.

In North America, Black, Indigenous, and other People Of Colour (BIPOC) communities have fought for hundreds of years to protect the air, land, water, species, and cultural connections to the land from discriminatory policies and actions, while the majority of the people spending time in nature for recreation are white.[2]

The map below shows just a few of the current examples of ongoing environmental injustice in Canada.

As we spoke of before with regard to trauma-informed education, this knowledge may shape how you connect with people who participate in your programs, or how you plan your programming while being sensitive to what ‘nature’ can mean for others. For some, being outdoors or near flowing water might be associated with dirtiness, pollution, or danger. Within your limits, speaking up about issues that are relevant to your place that may otherwise not be told is a part of Environmental and Justice Leadership.

Case Studies

Using the map below, click on different hotspots throughout Canada.

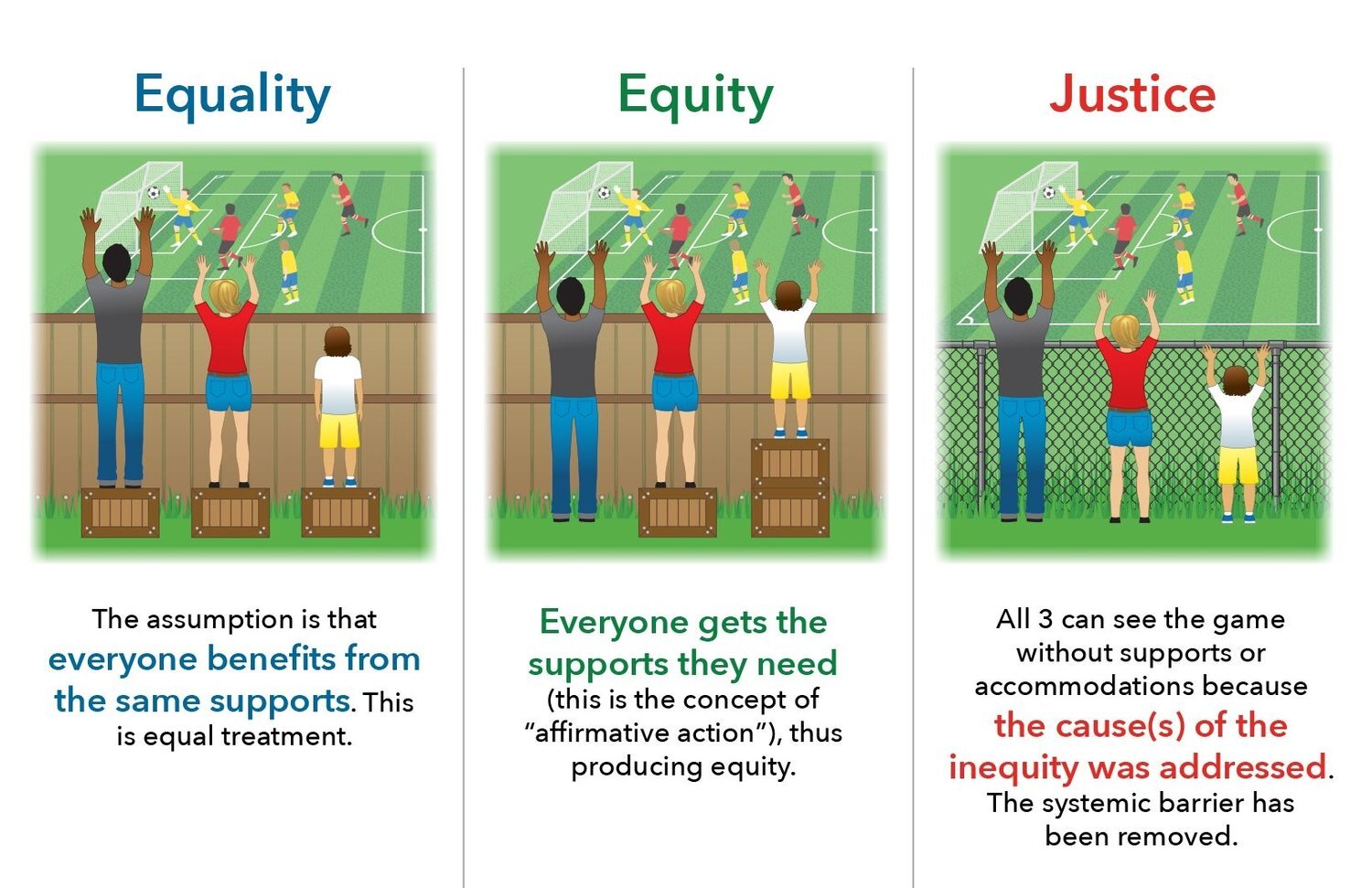

Key DefinitionsEquality, Equity, and Justice

|

Environmental Equality, Equity, and Justice

Environmental Equality – Everybody gets the same fair treatment.

Environmental Justice – Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, colour, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

Environmental Equity – Environmental equity describes a country, or world, in which no single group or community faces disadvantages in dealing with environmental hazards, disasters, or pollution. Ideally, no one should need extreme wealth or political connections to protect the wellbeing of their families and communities. Environmental equity is a basic human right.

If environmental equity is a basic human right, environmental justice is the act of protecting that right. Equity is the outcome of environmental justice. An equitable society is one in which justice has been served. These two concepts are complementary, not one in the same. It is also important to point out that different circumstances in people’s lives can lead to different outcomes in their health.

Health Equity – Health equity is created when individuals have the fair opportunity to reach their fullest health potential. Achieving health equity requires reducing unnecessary and avoidable differences that are unfair and unjust. Many causes of health inequities relate to social and environmental factors, including income, social status, race, gender, education, and physical environment. If people have grown up in environmentally unjust environments, their health may suffer.

For example, in the United States in 2020, non-Hispanic black people were almost three times more likely to die from asthma-related causes than the non-Hispanic white population.

In 2020, non-Hispanic black children had a death rate 7.6 times that that of non-Hispanic white children.[3] While studies in Canada are ongoing,[4] the growing body of evidence suggests that this is not solely genetic, or that gene-environment interactions are occurring, linked to environmental factors attributed to socioeconomic factors like exposure to nicotine and other allergens from poor housing.

As someone who is an educator, guide, professional, or leader in the outdoors, it is up to you to recognize your own implicit bias based on where you grew up and what environments and education you have had access to that have shaped how you feel and act in the outdoors and around groups of people who may have had different experiences with equity than you.

Taking time to assess if your programming is environmentally equitable and to ensure that you do not judge the person, especially youth, for health outcomes (obesity, asthma) is key as you move forward in your career.

These are great opportunities for you to embed into your programming, particularly with folks who love various forms of technology.

Journaling Prompt

Would you describe your upbringing and historical experience with nature and the outdoors as equitable?

Why or why not?

Accessibility and Inclusion in the Outdoors

Accessibility and inclusion are complex topics that need to be addressed and that are unique to each environment, organization, and individual. Separating programming for people with disabilities may be more equitable than inclusion in some spaces, whereas inherently excluding people with disabilities may be based on assumptions about people’s capabilities without having asked them for their input.

Karen Lai, Accessibility and Inclusion Coordinator for the City of Vancouver, leads honest and authentic conversations about inclusion by instilling a sense of curiosity, thus shifting the culture of inclusion. You can watch her video on ‘Accessibility and Inclusion in the Outdoors’ here.

The reality is that no one size fits all — it’s about asking questions, being curious, and looking at what needs to be done to really provide equity in an individual space or program.

Let’s conclude this course by looking back at the lessons learned throughout in the final section, Beyond the Field.

- Batisse, E., Goudreau, S., Baumgartner, J. et al. Socio-economic inequalities in exposure to industrial air pollution emissions in Quebec public schools. Can J Public Health 108, e503–e509 (2017). https://doi.org/10.17269/CJPH.108.6166 ↵

- Jacqueline L. Scott & Ambika Tenneti (2021). Race and Nature in the City:ENGAGING YOUTH OF COLOUR IN NATURE-BASED ACTIVITIES. A Community-based Needs Assessment for Nature Canada’s NatureHood. ↵

- Asthma and African Americans US Department of Health and Human Services https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/asthma-and-african-americans Accessed Nov 2, 2023 ↵

- Barnes KC, Grant AV, Hansel NN, Gao P, Dunston GM. African Americans with asthma: genetic insights. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007 Jan;4(1):58-68. doi: 10.1513/pats.200607-146JG. PMID: 17202293; PMCID: PMC2647616. ↵