Sharing Your Knowledge

You, Your Place, and Your Place Within Your Place

It isn’t enough to develop relationships with place or the land around you alone. Communicating your knowledge, interest, and passion to those you interact with, guide, or program for is a key part of being an Environmental Leader.

If you have participated in formal training to be an interpretative guide, you will know about ‘thematic planning.’ This is organizing your knowledge sharing into accessible and interesting themes and speaking to topics within each theme. For example, your theme could be ‘Climate Change is Cool’ and topics within that might be ‘Epic adaptations of local plants,’ ‘How we can all be scientists with just a camera and thermometer!’.

You will learn more later about getting comfortable with talking about challenging topics like climate change, but first let’s think about you, your place, and your place within that place.

Journaling Prompt

- Take a moment to think about a place that is special to you? Write down where it is; describe what it looks, smells, and feels like to be there. Why is it special to you?

- How might you connect participants with a feeling of ‘specialness’ in the place you will be together?

- To connect with what place-based learning means, whether you are building your own practice or delivering this as part of an environmental leadership role, work through the activity below to identify your awareness in place-based education design principles.

- Research land-based learning where you live or work. Are there people facilitating it? Can you participate to learn more?

- Copy down the table below and fill it in for your location or examples specific to you. We’ve given you an example.

Place Based Education Design Principles

![]()

| Characteristic | Our Example | Theme | Topic |

| Local to Global Context

Local learning serves as a model for understanding global challenges, opportunities, and connections. |

White Bark Pine

Facing the combined threats of habitat loss, climate change, the Mountain Pine Beetle, and Blister Rust, the Whitebark Pine’s BC population has been in decline for several years Topic: Humans and Pine. Because this species is not of commercial value, getting the tree recognized as endangered was challenging when researchers first tried to call attention to the issue. In 2012, it was added to the federal endangered species register under the Species at Risk Act. This evergreen, coniferous tree can be found in southern BC, east of the Coast-Cascade Mountains. Considered a keystone species, it is an important food source for many birds and small mammals, particularly for Clark’s Nutcrackers, which play an essential role in seed dispersal. What are the global trends in biodiversity? Are species in decline where your guests are from? How does the BC forestry industry connect to people around the world? (e.g., Toilet-paper roll made from ancient cedars shipped around the world) |

||

| Learner Centred

Learning is personally relevant to students and enables student agency. Asking guests what is important to them. Are you a person who loves to fish? Mountain biker? Painter? What impacts are you seeing in your local environment, and what action can you take? Are there local community groups/events you can connect with? What is important to you? |

Guests visiting Revelstoke can smell sewage downtown.

Knowing that this is due to an overwhelmed waste management system, primarily due to people flushing oils and fats down the drains and using more water than the system can pull through in summer droughts, can turn something gross into a real talking point about population density, pressures, and the role we can take as individuals (rather than blaming government/city). |

||

| Inquiry Based

Learning is grounded in observing, asking relevant questions, making predictions, and collecting data to understand the economic, ecological, and socio-political world. |

Collecting Data

Ask your participants open-ended questions. What changes do you expect to see in the next 25 years here? What do you think is vulnerable in this ecosystem? What do you think is resilient in this place? Living Lakes Canada offer free, simple water-testing kits to do community science. I test small water bodies that I visit regularly (takes 5 minutes). Simply paying attention to dying trees, or signs of stress in the environment. Watching for birds and adding your sightings to iNaturalist or another app. |

||

| Design Thinking

Design thinking provides a systematic approach for people to make a meaningful impact in their communities using existing structures. |

What can I do?

Brainstorm with people about what is relevant to their lives and place:

|

||

| Community as Classroom

Communities serve as learning ecosystems for people where local and regional experts, experiences, and place are part of the expanded learning or participatory experience |

Employ Local expertise

Participate or arrange for workshops in your area; attend them and learn. I’ve used local biologists for foraging or wild food or medicine workshops and learned in those spaces. Connect to Indigenous knowledge keepers if you have those relationships. Ask people what local expertise exists where they are. If they don’t know, get them to investigate! |

||

| Interdisciplinary Approach

Your programming/curriculum matches the real world where the traditional subject-area content, skills, and dispositions are taught through an integrated, interdisciplinary and frequently project-based approach where all participants are accountable and challenged. |

Gratitude on the trails

Taking the time to collect data as above, but also offering small scraps of paper and pencils for sketching, poetry, or moments of reflection deeply embed the experience in people’s emotions and memory. This also offers a chance for a break if people are tired on your trip or if you need to regroup. |

Community Engagement and Justice

As touched upon in the place-based learning design table above, communities serve as learning ecosystems, including if there is capacity to involve local Indigenous First Nations. Whether the people you demonstrate leadership with are local or visitors who may take this knowledge back to ‘their’ place, demonstrating community connections is one way to engage people in developing their own sense of environmental leadership.

Research shows that community partners have great success completing environmental projects that they themselves initiate and that are physically located nearby.[1] Inspiring participants with carrying a small trash bag to do litter picking as you hike, or relaying to them success stories of community collaboration within your sphere can create motivation for them to implement these programs themselves.

Being a part of yourself and encouraging your guests to participate in community projects like those that involve planting native species, restoring trails or habitats, or contributing to the overall health of a natural area can be incredibly rewarding.

We will speak more to environmental justice later in the course, but it is important to touch on the inequalities that exist in different places in relation to environmental justice. With visitors, especially youth from urban or low-income areas, you may have a very different perspective on community engagement.

It has previously been the case that “the environmental movement in Canada is dominated by a white, middle-class privileged population that finds it challenging to engage diverse communities and gain from their knowledge, skills, and experience.”[2] There has been tremendous work recently from organizations in the outdoor and environmental world to counteract and dispel this, with a strong emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion in programming.

Implementing a place-based inquiry approach to your leadership will ensure that you ask questions of your participants and can frame your approach around what is important and needed for them based on their responses. It can be ineffective to talk about, for example, restoring lakes if they live in-inner city Toronto and don’t feel connected to lakes.

Journaling Prompt

- What is a local community organization you can support, celebrate, volunteer for, connect with, or collaborate with for your work?

- What do they do and why is it important for the natural environment?

Nature and Its Many Stories

“To become naturalized is to live as if your children’s future matters, to take care of the land as if our lives and the lives of all our relatives depend on it. Because they do.”

– Robin Wall Kimmerer in Braiding Sweetgrass[3]

As you grow your environmental leadership skills, you will encounter people who hold differing worldviews on your journey. Nature and the outdoors can have very different meanings and connotations for people. Just as we talked about place as being a personal definition unique to the person, so will each person’s story be in outdoor or environmental spaces.

Our inherent social and cultural relationships have developed in relationship with the world around us. Different cultures have different special or revered plants and animals based on what is local and how humans and other beings have evolved together in a particular place.

In this place, it is now known that the stories from certain groups of people in Canada, particularly the Indigenous people here, have been suppressed, devalued, and discriminated against from the inception of colonialism in this country. There are also groups who did not come to Canada out of choice — slavery, forced labour, and immigration are major parts of Canadian history, too.[4]

While there has been important work to change this situation through interpretative recognition in museums, parks, and literature and through the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and their calls to action, it is important to recognize that our own lived experience may have left us with inherent bias and that the legacy of the devastating colonial damage, attempted genocide, racism, and abuse is ongoing and present.

Before we can spend time in nature and expect others to do so with us, we must acknowledge that there are an untold number of personal and lived experiences that lead us to our personal relationship with nature and our feelings about it. Some of these will be overwhelmingly positive, but others may have negative feelings related to nature spaces and their safety there.

It is important to share our own story within our education or sharing contexts but to also recognize the voices that might not be visible or present or that have historically faced barriers to being seen, heard, or shared about in nature spaces and places.

“For humans to get along with each other and to respect our relations on the earth, we must embrace and practise cognitive and cultural pluralism (value diverse ways of thinking and being). We need to not only tolerate difference but respect and celebrate cultural diversity as an essential part of engendering peace.”

– Melissa K. Nelson [5]

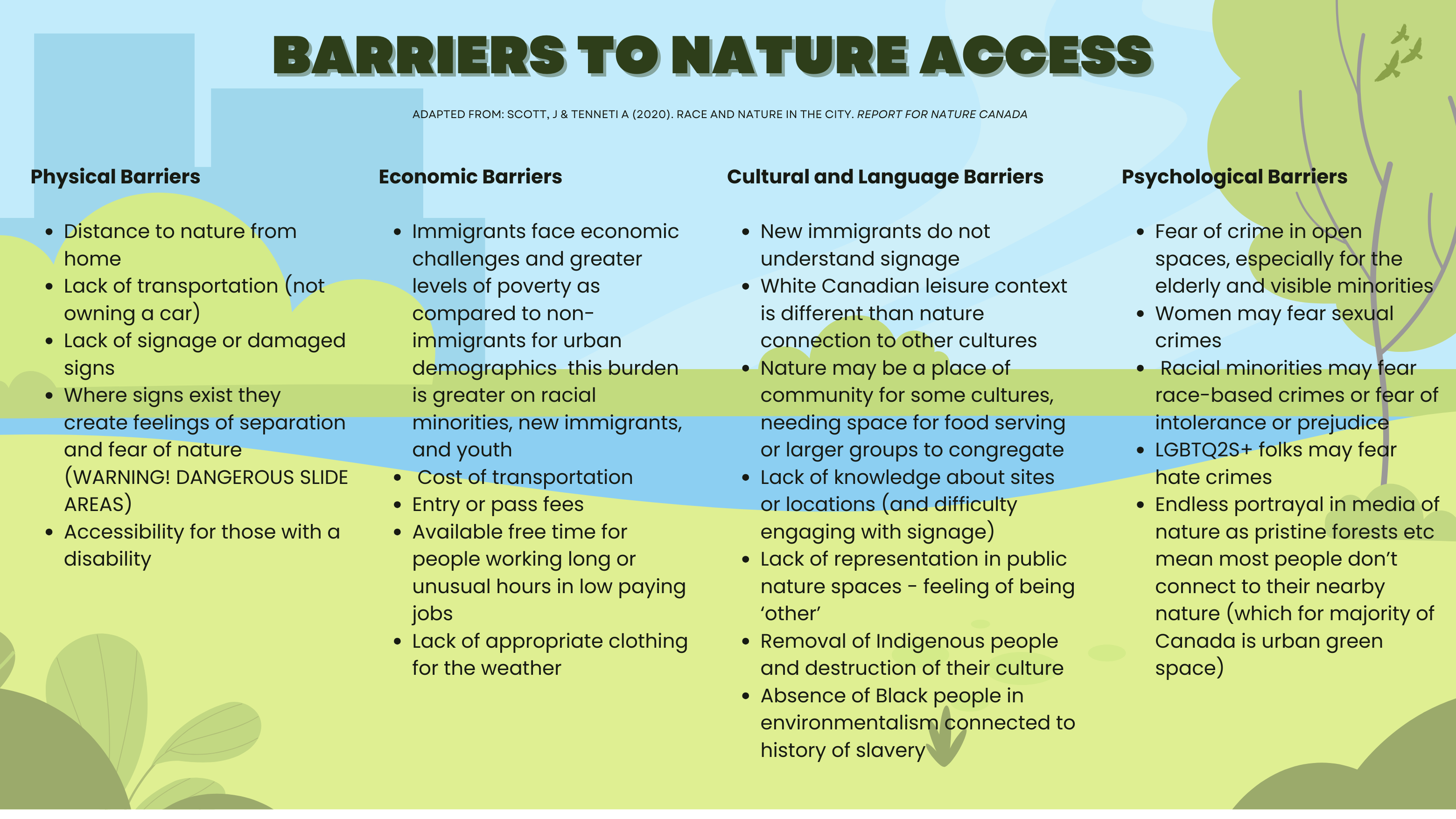

Jacqueline Scott and Ambika Tenneti in their report for Nature Canada identified numerous barriers to nature access for different groups. These barriers relate to knowledge and information, physical, economic, cultural, as well as psychological barriers. The research is summarized below in the infographic.

You can download or see this image in full screen by clicking here!

|

|

|---|

| ㅤ |

Listen to some different people speaking about their relationship with nature and the outdoors in the following video or podcast stories before moving onto the Journaling Prompt:

|

Journaling Prompt

- How does listening to these stories make you feel?

- Have you ever felt unsafe in nature? If so, for what different reasons?

- What could you do in your leadership role to ensure the safety and wellbeing of racialized or other marginalized groups of people in your programming or life?

Erasure of Indigenous Perspectives

“The land is not just land. It is medicine, it is history, it is culture. We must care for the land, working together, all of us, Indigenous and non-indigenous, or we will lose what keeps us healthy.”

– Mike Archie, Former Chief of Canim Lake Band, Cultural Advisor to Shuswap Indian Band

It is important to recognize that as you research, deepen, and develop your knowledge of place where you will be guiding or operating, you must recognize the limitations or lack of representation in some published literature or pedagogy.

If you are sharing botanical, etymological, or historical interpretive information, are you sharing a well-rounded overview of different viewpoints? The colonization of Canada has meant that in mainstream educational institutions and beyond, often only a Eurocentric viewpoint and knowledge-sharing systems have been acknowledged, honoured, or recognized as valuable.

Whether looking at a diverse First Nations approach to education in Canada, relationship and Traditional Ecological Knowledge, or other Indigenous or cultural groups globally, there are myriad ways of disseminating information, interpreting the world around us, and sharing knowledge that has long been dismissed or ignored by colonial powers.

Whether we share a particular knowledge system ourselves, it is important to recognize and acknowledge other systems to participate in a more equitable society and become true leaders for the environment.

It is also important to educate ourselves on the truth of Canadian history, including continued systemic racism and discrimination. Listen to ‘The Right to Know’ podcast here to learn just one story of truth and take personal action for reconciliation (beyond the one day on September 30th for National Day for Truth and Reconciliation).

You can also download a free ‘How to be an Ally’ PDF guide here.

5 Steps You Can Take to Become an Ally

- Read the 96 calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

- Which of these can you take action on in your daily life or work?

- Learn the names and how to contact the local First Nations where you live or work. Practice pronouncing their names and the name of the language of the land. Offering a Land Acknowledgement can be a way to honour those who have lived in this place for thousands of years and until recently were suppressed or ignored and have lost rights to their land. That said, tick-box, standard, regurgitated Land acknowledgements should be avoided. Your land acknowledgement should be…

- a) Unique each time and relevant to how you are feeling that day and specifically where you are.

- b) Not just of the names of the groups of people of the Land, but what does that mean to you (often in terms of what are you grateful for, what do you notice around you or what is happening with the land that is important?) and what does it compel you to do? (Protect, journal, sketch, share it).[7]

- Reach out to a local Indigenous community, attend Indigenous-led events (where the general population is invited), buy from local Indigenous creators, and ask questions about them and their land.

- Offer more than you ask for — research about local place, plant, or animal names in the local language before asking local Indigenous people to translate or share their knowledge.

- Offer gifts or honoraria in exchange for any information shared. Research the protocol for your local First Nation or Indigenous Friendship Society to get a better understanding of how to connect where you are.

Case Study: ‘Crowd Science’ by the BCCAn example of a singular-focused view can be heard in this podcast episode of ‘CrowdScience’ from the BBC. The science reporters are asked to research certain questions by members of the public and the radio show hosts go out to find scientific experts to answer these. You can see the list of top scientists in the graphic below.

In the episode above, they are investigating the way that climbing plants will seek out strong support as if they know what they are doing. The presenters, science journalists and communicators, and scientists (all Western), despite repeatedly sharing that they don’t understand the mechanism for how these plants are able to detect different shapes, sizes, directions and in fact make active choices about which support to take, repeatedly state that the plants are not thinking, do not have a centralized brain, and thus can’t be consciously doing this. There is one professor who seems to state a certain possibility of mechanisms or consciousness we don’t have the tools to understand, but each person dismisses the consciousness of plants. Indigenous scholars like Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer or Elder Chief Mike Archie of the Shuswap Indian Band share that plants are people in their culture. Mike Archie shared, “Plants are the medicine people, alive, a vital part of our community, working hard to keep us [humans] healthy and well.” How is it that this as-yet-unexplained-by-science phenomenon, despite vigorous genetic, chemical and physical testing, has never included asking those with alternative knowledge systems to help fill the knowledge gap? With an openness to learn, ask questions, and build relationships, we hope this can change for the future.

|

|

|

|---|

| ㅤ |

|

Think: What is your personal story with nature? ○ What good things have happened to you there? ○ What difficulties or hardships have you encountered? ○ What is the impact of these experiences on your work?

Describe your own personal learning framework: ○ Where did you get your knowledge? ○ Was it all in formal institutions and Eurocentric systems? ○ If not, how or by whom was this shared?

Research an alternative way of learning that resonates with you and your place: ○ What is the value of your lived experience to date? ○ What is the value of this alternative thought and how can it improve your environmental leadership skills?

Understanding the above will be very helpful for the sections to come. |

Climate Change Education

It is now widely accepted within the scientific community (at least 97.1% agree)[8] that anthropogenic climate change (humans impacting the natural climatic cycles) is occurring. In an online survey for Environment Canada in 2023, 60% of Canadians think climate change is a fact and is mostly caused by emissions from vehicles and industrial facilities. But despite the worst wildfire, flood, and drought seasons across the country, this figure is down 9% since a similar poll conducted in August 2022.

More than one-in-four Canadians (27%, +7) think global warming is a fact and is mostly caused by natural changes, while 8% (+3) say climate change is a theory that has not yet been proven.

More than three-in-five residents of Atlantic Canada (63%), Quebec (63%), and Ontario (61%) think global warming is human-caused. The proportions are lower in British Columbia (58%), Saskatchewan and Manitoba (55%), and Alberta (52%).

The reality is that Canada is warming at twice the rate of the global average.[9] As Catherine McKenna, Minister of Environment and Climate Change, shares…

“Climate change is real, and Canadians across the country are feeling its impacts. The science is clear; we need to take action now. Practical and affordable solutions to fight climate change will help Canadians face the serious risks to our health, security, and economy, and will also create the jobs of tomorrow and secure a better future for our kids and grandkids.”

As we live in a time of mass information dissemination through online media and social media, it can be challenging to verify such quantities of information. We all have biases, and as such, it can be difficult to accept new worldviews on this topic, especially for young people, older generations, or those who work in primary resource or fossil fuel industries. Public trust in scientists and government has also seen polarizing shifts and decreases in trust, often linked to political parties or ideologies and particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic and the meeting of science and state.

This can lead to challenging conversations with our participants. It is our role as communicators, guides, and those spending time in our natural environment to share good information with our guests, clients, or work communities (to the best of our knowledge) and to create space to centre the discussion and offer action for Environmental Leadership.

Let’s continue on and take a look at Climate Change Education.

- Vivek Shandas & W. Barry Messer (2008) Fostering Green Communities Through Civic Engagement: Community-Based Environmental Stewardship in the Portland Area, Journal of the American Planning Association, 74:4, 408-418, DOI: 10.1080/01944360802291265 ↵

- Gibson-Wood, H. (2010). Exploring Environmental Justice and Interrogating ‘Community Engagement’: A Case Study in the Latin American Community of Toronto (Doctoral dissertation) ↵

- Kimmerer, R. W. (2015). Braiding sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions. p215. ↵

- https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/population/slavery/#:~:text=The%20historian%20Marcel%20Trudel%20catalogued,the%20course%20of%20this%20period. Accessed Oct 1, 2023. ↵

- Nelson, M. K. (Ed.). (2008). Original instructions: Indigenous teachings for a sustainable future. Simon and Schuster. ↵

- Adapted from Jacqueline L. Scott & Ambika Tenneti (2021). Race and Nature in the City: ENGAGING YOUTH OF COLOUR IN NATURE-BASED ACTIVITIES. A Community-based Needs Assessment for Nature Canada’s NatureHood. ↵

- Verbal instructions from Lower Nicola Band Member and ACMG Guide Tim Patterson to the Author. ↵

- Reusswig, Fritz. “History and future of the scientific consensus on anthropogenic global warming. ” Environmental Research Letters 8.3 (2013). ↵

- Environment Canada (2019) Accessed June Sept 16 2024 https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/news/2019/04/canadas-climate-is-warming-twice-as-fast-as-global-average.html ↵