Defining Environmental Leadership in Outdoor Education

The 4 Aspects of Environmental Leadership

Based on research and practice, we see four primary focal areas in environmental leadership that we can address through this work:

- Conservation/Community Science

- Outdoor Learning — including Environmental Education and Place Based Learning

- Community Engagement and Justice

- Sustainable Practices for field and beyond

Later, we will share a framework for you to build your leadership skills in each of these areas.

Conservation/Community Science

![]()

Community science (sometimes referred to as citizen science, but we avoid this term due to the implication of needing to be a ‘citizen’ of a place to engage in it) includes active involvement of ordinary people in scientific projects. By collecting data and observing patterns in the environment around them, community scientists are able to contribute significantly to scientific research. Major citizen-science initiatives such as eBird, INaturalist Bioblitz, and Living Lake Canada’s National Lake Blitz allow everyday people to contribute to the understanding of bird, animal, fungi, and plant populations; nesting habits; and water quality with little or no expertise.

Community science is a collective effort for scientific solutions at the community level. This type of grassroots research usually involves community members taking ownership of their environment through data gathering and observational analysis.

Community scientists can work directly with municipal governments or environmental organizations to develop strategies for managing resources in their area. It is also possible for community scientists to inform policy decisions, identify research trends, and monitor environmental changes in their communities.

|

|

The benefits of community science are numerous. By engaging local stakeholders in the research process, community scientists can ensure that the research is tailored to the specific needs of the community. Additionally, community science can help bridge the gap between scientific research and the public, allowing for a more informed and engaged citizenry. Finally, community science can help create a sense of ownership and pride in the community, as citizens are empowered to take an active role in the research process.

These are great opportunities for you to embed into your programming, particularly with folks who love various forms of technology.

Journaling Prompt

- Have you ever participated in community science?

- Research a program that you could participate in coming up soon with a national or local community organization. It could be counting amphibians or birds, water testing, creek clean ups, or invasive species removal.

- What are the benefits of the project you have chosen for the natural environment and community?

Outdoor Education or Learning

![]()

Outdoor Education or Learning is a broad term that includes outdoor play in the early years, school grounds projects, place-based learning, environmental education, climate change education, recreational and adventure activities, personal and social development programs, expeditions, team building, leadership training, management development, education for sustainability, adventure therapy… and more (Institute for Outdoor Learning, 2021).

Each of us is an educator, however informal. When we share spaces, where we are holders of knowledge — as guides or leaders — we are educating both explicitly and in subtle ways through those who spend time, mirror, or reflect on our behaviours.

The joy of this diverse ‘outdoor learning’ concept is its relatability to all people, and its reconnecting us with our place as a part of nature, whether we are on a corporate team-building trip or guided trip. There is much to be learned from diverse perspectives on connection to the environment, particularly from Indigenous people and their recognition of intergenerational environmental stewardship.

“Land is memory. Water is sacred. All living things are connected.”

– Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources (CIER)

Journaling Prompt

- Do you agree with the above statement?

- What resonates with you?

- Is there anything you disagree with or find difficult to relate to? If so, why?

Environmental Education

![]()

Beyond just spending time outdoors, Environmental Education (EE), Environmental Literacy, and Environmental Leadership require people to connect with the complex interrelationships between human culture and ecosystems.

Environmental Education (EE) is a process in which individuals gain awareness of their environment and acquire knowledge, skills, values, experiences, and also the determination, which will enable them to act — individually and collectively — to solve present and future environmental problems.

It requires intention in the way you work, live, or play in wild spaces — not necessarily the most experience as a scientist or in the environmental field itself. Intention can be focusing on being present (not looking at your phone as you hike), noticing more, actively picking up trash, or starting your time outside with gratitude. We’ll touch on this more later in the course.

Learning outdoors has been the norm for most of human history. Before the colonial settlers removed traditional knowledge-sharing structures, Indigenous cultures of North America and beyond have educated their next generations through outdoor and experiential methods, recognizing with equal importance…

- Physical Connection: Earliest cultures have a traditional way to use land and what is upon it — the obvious being the use of land for making things such as shelter and tools to aid in living off the land. These cultures have a traditional diet as well as immense knowledge of plants, animals, and their properties. Traditional stories inform successive generations about the connections and significance of symbolism — symbolism that connects their culture to the land and all those who inhabit it. By observing the land and how it speaks, Indigenous cultures have learned how to move with and respect it.

- Spiritual Connection: Local Indigenous cultures have a common belief that the Earth is alive and that all things are related. One universal aspect that Indigenous cultures can teach us is to respect the spirit in all things. When we acknowledge its spirit; when we communicate with and respect it, it becomes alive. The respect that we show to other things is embedded in the ways our cultural groups have been taught for generations.

- Cultural and Emotional Connection: This teaches us how to communicate with all things, including the land. Before we can really see how a relationship with the land is fostered, we must understand culture in a way that is all-encompassing of the potentially different knowledge and belief systems of that culture.[1]

As technological and industrial advances have continued, shifts in our relationship with the outdoors have occurred in western society. We began to spend more time indoors, and education moved indoors in most learning institutions.

There are countries — such as Denmark, Finland, Singapore, and New Zealand — that have always championed outdoor learning, but others have mistakenly not valued the outdoors as ‘real’ learning spaces. In the United States in the late 19th century, educators realized that getting students out of the classroom could “improve educational skills, attitudes, and values,”[2] educational reforms since the 2000’s have had an increased focus on outdoor learning and the recent Covid-19 pandemic solidified the importance of outdoor learning and play for Canadian wellbeing.[3] There is overwhelming evidence that outdoor learning is good for us physically, mentally, socially, emotionally, and academically,[4] but the trends in population don’t always match the underpinning knowledge.

According to a national survey by ParticipACTION conducted in April of 2020, a month after the World Health Organization declared the virus a global pandemic, “less than 3% of Canadian 5–17 year-olds were meeting the minimum recommendations in the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep — in contrast to 15% before the health crisis.”[5]

In contrast, in a 2022 poll from the Nature Conservancy of Canada, three in four Canadians stated that time spent outdoors is “more important to them now than ever before,” and nine in 10 Canadians said there needs to be a “greater investment in restoring and caring for the natural areas across Canada.”[6]

Environmental Education and the ability to build connections among ourselves, nature, and all parts of the environment is increasingly important for the wellbeing of humans and all living and nonliving things in our ecosystems.

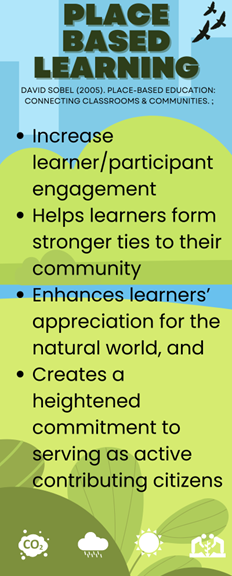

Place Based Learning

![]()

|

Place is any environment, locality, or context with which people interact to learn, create memory, reflect on history, connect with culture, and establish identity. To excel in your professional lives, the ability to connect to ‘place’ and draw others into establishing their own connections is key to being an effective environmental leader. When we apply a place-based approach to our own learning, sharing of knowledge, or leadership, we can see great benefits. Place based learning offers the chance to build communication and collaboration skills; deepen creative, critical, and reflective thinking; and enhance personal and cultural identity as well as social awareness and responsibility. In July 2022, The UN General Assembly (UNGA) passed a resolution recognizing the right to a ‘clean, healthy, and sustainable environment’ as a human right. As you work within your place for sustainability and environmental health, within the connected systems of our planet, you work in it for everybody. You are helping to support the future wellbeing of this planet and the rights of the humans who inhabit it. In the Canadian context, it is also important to mention the concept of… |

Land Based Learning

![]()

Land has played an integral role in Indigenous education since time immemorial. In Indigenous ways of knowing and being in the world, land is the basis of all life and therefore the foundation for all cultural and traditional teachings. Learning takes place in cooperation with the rhythms of everyday life, including land-based activities such as hunting and gathering. This form of education is in contrast with Western systems that continue to perpetuate colonialism through the erasure of Indigenous lives, cultures, and knowledge.[7]

Many of the running or competitive games we see today in schoolyards can be traced back to Indigenous games that were intended to train youth for successful lives in relationship with land and the outdoors — mimicking hunting, trapping, or tracking skills and building fitness.

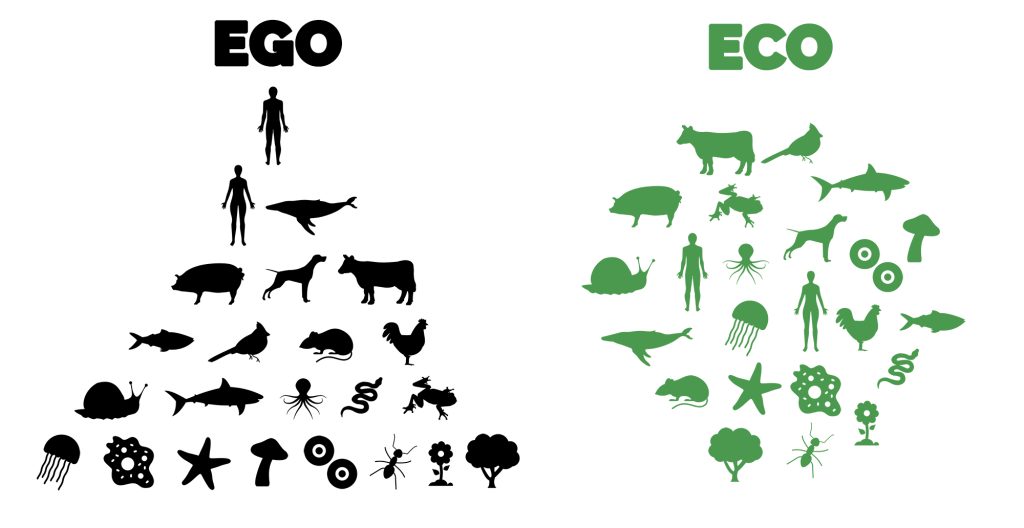

The traditional ecological knowledge of land, nature, or the outdoors, while individual to the diverse First Nations of Canada, can be generalized as something that identifies humans as a part of rather nature rather than something we ‘use’ or ‘go to’[8] and can be recognized as a relationship that is eco centric rather than ego centric without a hierarchy of life that puts humans firmly at the top.

The depth, value, and variety of knowledge, wisdom, and relationship with the environment that Indigenous peoples in Canada have managed to retain despite systematic assimilation, racism, and genocide is incredible and beyond the scope of this training. It is, however, important to acknowledge Indigenous perspectives in our work through acknowledging the truth of colonialism and taking active steps toward reconciliation. More recommendations can be found later in this course, but for now, we can recommend some reading.

Recommended Reading

|

|

A great resource, especially for those who work with youth or offer hiking programming is ‘Walking Forward’ by Gillian Judson and Heidi Wood (from Network of Inquiry and Indigenous Education (NOIIE)0. It incorporates First Peoples Principles of Learning and is available as a Free Download. |

|

Braiding Sweetgrass for Young Adults – Monique Gray Smith’s adaptation of Robin Wall Kimmer’s classic. Features thought-provoking discussion topics related to the world around us, Indigenous knowledge, science, and spirituality. It has beautiful illustrations and is relevant for audiences of all ages. |

Sustainable Practices

![]()

When modelling and bringing awareness to sustainable practices — such as appropriate trail and wilderness etiquette in the leave-no- trace approach, renewable energy, waste prevention and recycling practices, alternative transportation, sustainable business, or organic agriculture — creating space for discussion and uplifting sustainable practices can be very important for your work.

We’ll give examples of success stories in sustainable practices later on in the course.

An absolute baseline we should adhere to and share with guests or participants is the ‘Leave No Trace’ 7 Principles. These can be shared as part of your opening circle or group meeting.

Sustainable practices that you should also consider:

- Stay on designated trails.

- Plan to avoid using the most heavily trafficked trails to minimize impacts.

- Use reusable water bottles and encourage participants to do the same.

- Use renewable energy power banks or clothing from environmentally friendly brands where possible.

- Be mindful of your food waste, and try to create less waste or do ‘zero-waste lunches’. Homemade energy balls or bars taste way better and can be cheaper than store-bought!

- Avoid games/activities that include moving/removing natural items from their place.

- Be very thoughtful about noise and litter pollution when moving through sensitive ecological areas.

- Encourage donations to trail or ecosystem stewardship programs.

Test Your Knowledge!

Drag and drop the prompts at the bottom of this 7 Principles graphic onto the appropriate category. You can check your work by clicking on the Check bubble at the bottom of the graphic.

Journaling Prompt

- What sustainable practices do you already conduct in your daily life?

- What are three things you could add to that list?

- If you’re stumped, you can check out this list from the Centre of Biological Diversity

Let’s continue on, and learn about Sharing Your Knowledge.

- Understanding Who We Are and Where We’ve Come From (2020). Learningtheland.ca (Accessed August 14, 2023). ↵

- Wattchow B (2006) Playing with an unstoppable force: paddling, river-places and outdoor education. J Outdoor Environ Educ 11(1):10–20 ↵

- Burke et al. (2021). Children’s wellness: outdoor learning during Covid-19 in Canada. Education in the North, 28(2) pp. 24-45. ↵

- Children and Nature Network (2016) Nature Can Improve Health and Wellbeing https://eadn-wc04-796033.nxedge.io/wp-content/uploads/CNN20_BNHealth-and-Wellbeing_23-3-24.pdf ↵

- De Lannoy, L., (2020, July 8). National survey of children and youth shows COVID-19 restrictions linked with adverse behaviours. Outdoor Play Canada. https://www.outdoorplaycanada.ca/2020/07/08/national-survey-of-children-and-youth-shows-covid-19- Restrictions-linked-with-adverse-behaviours/ ↵

- https://www.natureconservancy.ca/en/who-we-are/news-room/news-releases/canadians-urge-nature-protection.html (Accessed July 1, 2023) ↵

- Alfred, T. 2014. The Akwesasne cultural restoration program: A Mohawk approach to land-based education. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society 3(3): 134–14 ↵

- Nelson, M. 2008.Original instructions : indigenous teachings for a sustainable future. Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. ↵