13.4 Phase Diagrams

Learning Objectives

- Explain the construction and use of a typical phase diagram

- Use phase diagrams to identify stable phases at given temperatures and pressures, and to describe phase transitions resulting from changes in these properties

- Describe the supercritical fluid phase of matter

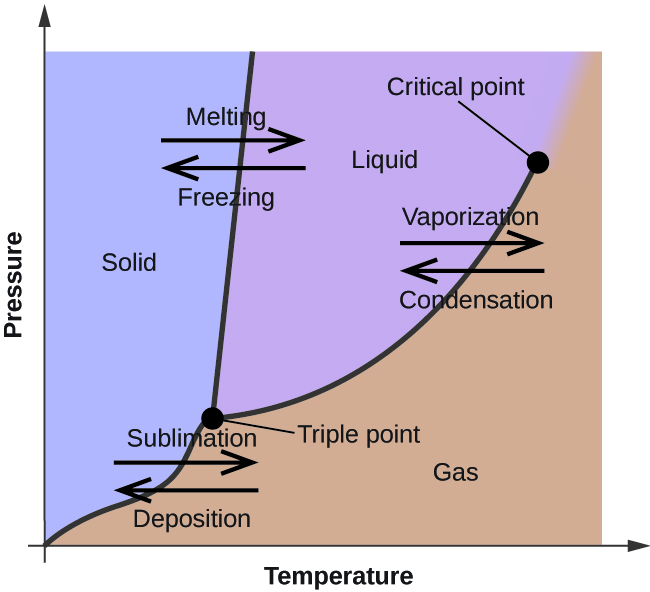

In the previous module, the variation of a liquid’s equilibrium vapour pressure with temperature was described. Considering the definition of boiling point, plots of vapour pressure versus temperature represent how the boiling point of the liquid varies with pressure. Also described was the use of heating and cooling curves to determine a substance’s melting (or freezing) point. Making such measurements over a wide range of pressures yields data that may be presented graphically as a phase diagram. A phase diagram combines plots of pressure versus temperature for the liquid-gas, solid-liquid, and solid-gas phase-transition equilibria of a substance. These diagrams indicate the physical states that exist under specific conditions of pressure and temperature, and also provide the pressure dependence of the phase-transition temperatures (melting points, sublimation points, boiling points). A typical phase diagram for a pure substance is shown in Figure 13.4a.

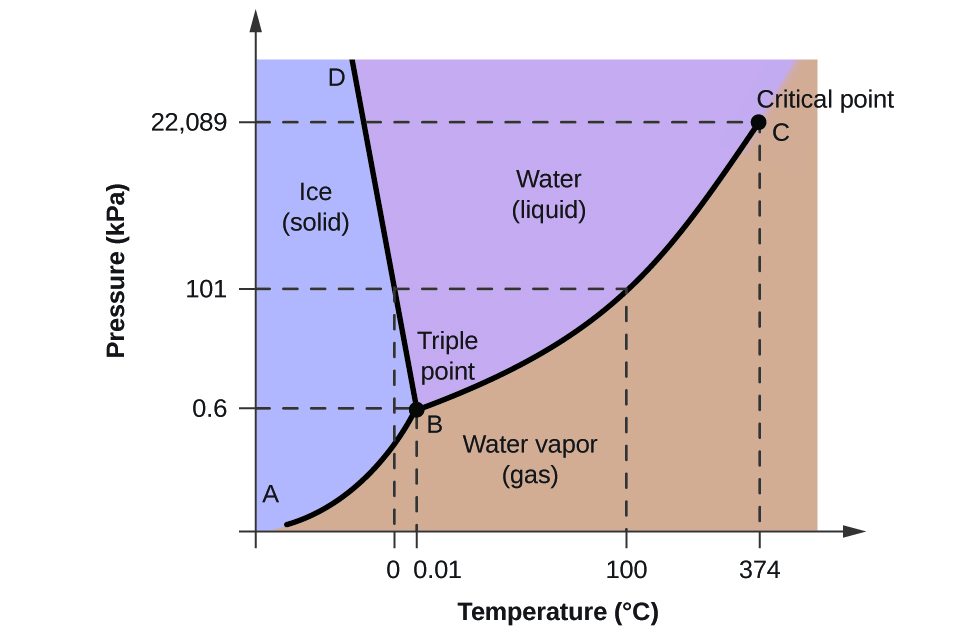

To illustrate the utility of these plots, consider the phase diagram for water shown in Figure 13.4b.

We can use the phase diagram to identify the physical state of a sample of water under specified conditions of pressure and temperature. For example, a pressure of 50 kPa and a temperature of −10 °C correspond to the region of the diagram labeled “ice.” Under these conditions, water exists only as a solid (ice). A pressure of 50 kPa and a temperature of 50 °C correspond to the “water” region—here, water exists only as a liquid. At 25 kPa and 200 °C, water exists only in the gaseous state. Note that on the H2O phase diagram, the pressure and temperature axes are not drawn to a constant scale in order to permit the illustration of several important features as described here.

The curve BC in Figure 13.4b is the plot of vapour pressure versus temperature as described in the previous module of this chapter. This “liquid-vapour” curve separates the liquid and gaseous regions of the phase diagram and provides the boiling point for water at any pressure. For example, at 1 atm, the boiling point is 100 °C. Notice that the liquid-vapour curve terminates at a temperature of 374 °C and a pressure of 218 atm, indicating that water cannot exist as a liquid above this temperature, regardless of the pressure. The physical properties of water under these conditions are intermediate between those of its liquid and gaseous phases. This unique state of matter is called a supercritical fluid, a topic that will be described in the next section of this module.

The solid-vapour curve, labeled AB in Figure 13.4b, indicates the temperatures and pressures at which ice and water vapour are in equilibrium. These temperature-pressure data pairs correspond to the sublimation, or deposition, points for water. If we could zoom in on the solid-gas line in Figure 13.4b, we would see that ice has a vapour pressure of about 0.20 kPa at −10 °C. Thus, if we place a frozen sample in a vacuum with a pressure less than 0.20 kPa, ice will sublime. This is the basis for the “freeze-drying” process often used to preserve foods, such as the ice cream shown in Figure 13.4c.

The solid-liquid curve labeled BD shows the temperatures and pressures at which ice and liquid water are in equilibrium, representing the melting/freezing points for water. Note that this curve exhibits a slight negative slope (greatly exaggerated for clarity), indicating that the melting point for water decreases slightly as pressure increases. Water is an unusual substance in this regard, as most substances exhibit an increase in melting point with increasing pressure. This behaviour is partly responsible for the movement of glaciers, like the one shown in Figure 13.4d. The bottom of a glacier experiences an immense pressure due to its weight that can melt some of the ice, forming a layer of liquid water on which the glacier may more easily slide.

The point of intersection of all three curves is labeled B in Figure 13.4b. At the pressure and temperature represented by this point, all three phases of water coexist in equilibrium. This temperature-pressure data pair is called the triple point. At pressures lower than the triple point, water cannot exist as a liquid, regardless of the temperature.

Example 13.4a

Determining the State of Water

Using the phase diagram for water given in Figure 13.4b, determine the state of water at the following temperatures and pressures:

- −10 °C and 50 kPa

- 25 °C and 90 kPa

- 50 °C and 40 kPa

- 80 °C and 5 kPa

- −10 °C and 0.3 kPa

- 50 °C and 0.3 kPa

Solution

Using the phase diagram for water, we can determine that the state of water at each temperature and pressure gave are as follows:

- solid;

- liquid;

- liquid;

- gas;

- solid;

- gas.

Exercise 13.4a

What phase changes can water undergo as the temperature changes if the pressure is held at 0.3 kPa? Is the pressure held at 50 kPa?

Check Your Answer[1]

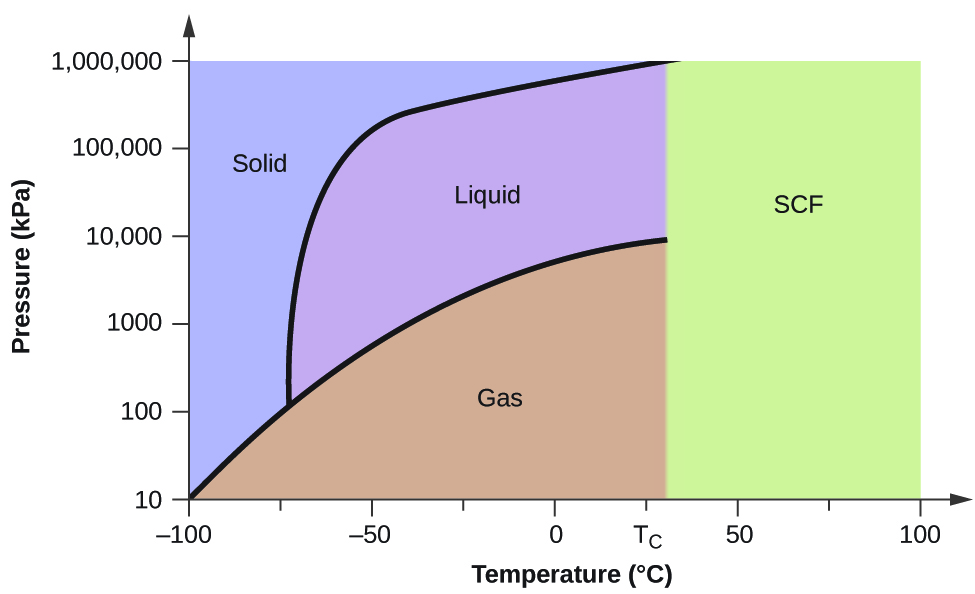

Consider the phase diagram for carbon dioxide shown in Figure 13.4e as another example. The solid-liquid curve exhibits a positive slope, indicating that the melting point for CO2 increases with pressure as it does for most substances (water being a notable exception as described previously). Notice that the triple point is well above 1 atm, indicating that carbon dioxide cannot exist as a liquid under ambient pressure conditions. Instead, cooling gaseous carbon dioxide at 1 atm results in its deposition into the solid state. Likewise, solid carbon dioxide does not melt at 1 atm pressure but instead sublimes to yield gaseous CO2. Finally, notice that the critical point for carbon dioxide is observed at a relatively modest temperature and pressure in comparison to water.

Example 13.4b

Determining the State of Carbon Dioxide

Using the phase diagram for carbon dioxide shown in Figure 13.4e, determine the state of CO2 at the following temperatures and pressures:

- −30 °C and 2000 kPa

- −60 °C and 1000 kPa

- −60 °C and 100 kPa

- 20 °C and 1500 kPa

- 0 °C and 100 kPa

- 20 °C and 100 kPa

Solution

Using the phase diagram for carbon dioxide provided, we can determine that the state of CO2 at each temperature and pressure given are as follows:

- liquid;

- solid;

- gas;

- liquid;

- gas;

- gas.

Exercise 13.4b

Determine the phase changes carbon dioxide undergoes when its temperature is varied, thus holding its pressure constant at 1500 kPa? At 500 kPa? At what approximate temperatures do these phase changes occur?

Check Your Answer[2]

Supercritical Fluids

If we place a sample of water in a sealed container at 25 °C, remove the air, and let the vaporization-condensation equilibrium establish itself, we are left with a mixture of liquid water and water vapour at a pressure of 0.03 atm. A distinct boundary between the more dense liquid and the less dense gas is clearly observed. As we increase the temperature, the pressure of the water vapour increases, as described by the liquid-gas curve in the phase diagram for water (Figure 13.4b), and a two-phase equilibrium of liquid and gaseous phases remains. At a temperature of 374 °C, the vapour pressure has risen to 218 atm, and any further increase in temperature results in the disappearance of the boundary between liquid and vapour phases. All of the water in the container is now present in a single phase whose physical properties are intermediate between those of the gaseous and liquid states. This phase of matter is called a supercritical fluid, and the temperature and pressure above which this phase exists is the critical point (see video below). Above its critical temperature, a gas cannot be liquefied no matter how much pressure is applied. The pressure required to liquefy a gas at its critical temperature is called critical pressure. The critical temperatures and critical pressures of some common substances are given in Table 13.4a.

| Substance | Critical Temperature (K) | Critical Pressure (atm) |

|---|---|---|

| hydrogen | 33.2 | 12.8 |

| nitrogen | 126.0 | 33.5 |

| oxygen | 154.3 | 49.7 |

| carbon dioxide | 304.2 | 73.0 |

| ammonia | 405.5 | 111.5 |

| sulfur dioxide | 430.3 | 77.7 |

| water | 647.1 | 217.7 |

Watch Supercritical CO2 (5 mins)

Video source: mrmrobin. (2012, May 20). Supercritical CO2 [Video]. YouTube.

Like a gas, a supercritical fluid will expand and fill a container, but its density is much greater than typical gas densities, typically being close to those for liquids. Similar to liquids, these fluids are capable of dissolving nonvolatile solutes. They exhibit essentially no surface tension and very low viscosities, however, so they can more effectively penetrate very small openings in a solid mixture and remove soluble components. These properties make supercritical fluids extremely useful solvents for a wide range of applications. For example, supercritical carbon dioxide has become a very popular solvent in the food industry, being used to decaffeinate coffee, remove fats from potato chips, and extract flavour and fragrance compounds from citrus oils. It is nontoxic, relatively inexpensive, and not considered to be a pollutant. After use, the CO2 can be easily recovered by reducing the pressure and collecting the resulting gas.

Example 13.4c

The Critical Temperature of Carbon Dioxide

If we shake a carbon dioxide fire extinguisher on a cool day (18 °C), we can hear liquid CO2 sloshing around inside the cylinder. However, the same cylinder appears to contain no liquid on a hot summer day (35 °C). Explain these observations.

Solution

On a cool day, the temperature of the CO2 is below the critical temperature of CO2, 304 K or 31 °C (Table 13.4a), so liquid CO2 is present in the cylinder. On a hot day, the temperature of the CO2 is greater than its critical temperature of 31 °C. Above this temperature, no amount of pressure can liquefy CO2 so no liquid CO2 exists in the fire extinguisher.

Exercise 13.4c

Check Your Learning Exercise (Text Version)

Ammonia can be liquefied by compression at room temperature; oxygen cannot be liquefied under these conditions. Why do the two gases exhibit different behaviour?

- The critical temperature of ammonia is 405.5 K, which is higher than room temperature. The critical temperature of oxygen is below room temperature; thus oxygen cannot be liquefied at room temperature.

- The critical temperature of ammonia is 405.5 K, which is lower than room temperature. The critical temperature of oxygen is above room temperature; thus oxygen cannot be liquefied at room temperature.

- Ammonia is at the lower level in the periodic table compared to Oxygen; thus oxygen cannot be liquefied at room temperature.

- Oxygen is present in abundant compared to oxygen; thus oxygen cannot be liquefied at room temperature.

Check Your Answer[3]

Source: "Exercise 13.4c" is adapted from "Example 10.4-3" in General Chemistry 1 & 2, a derivative of Chemistry (Open Stax) by Paul Flowers, Klaus Theopold, Richard Langley & William R. Robinson, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

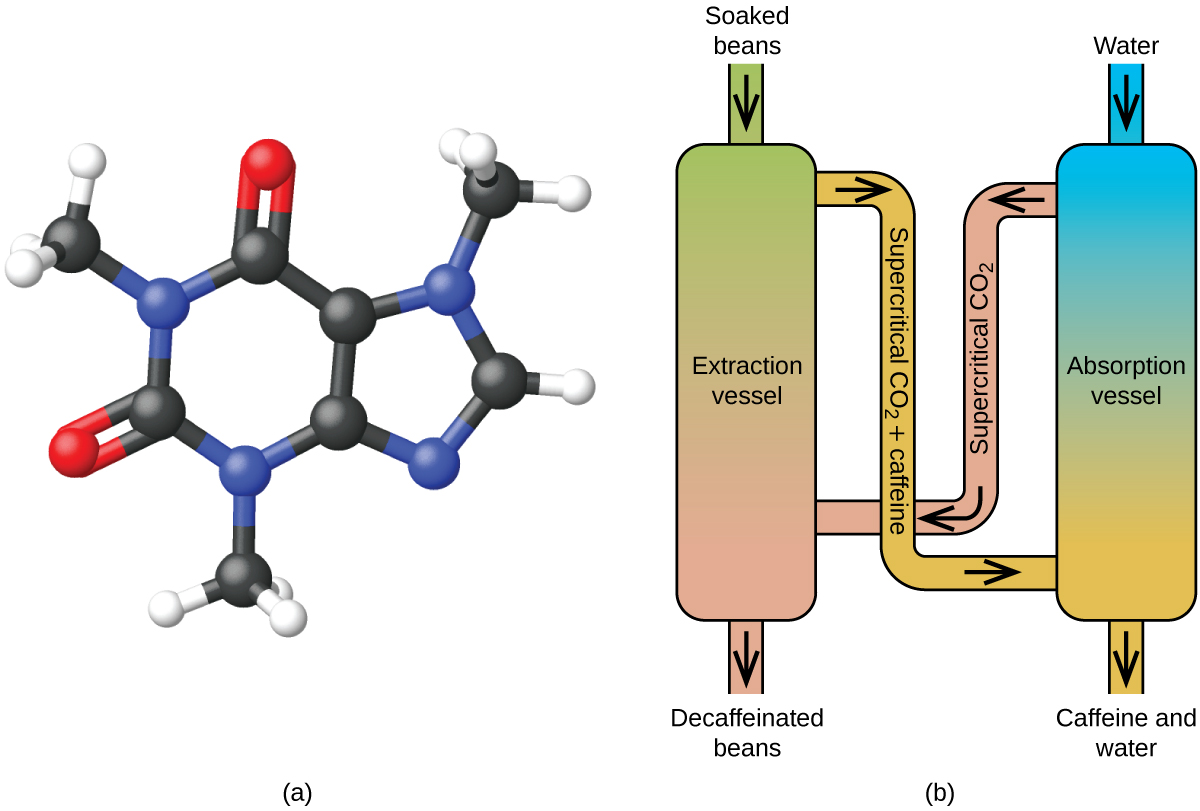

Decaffeinating Coffee Using Supercritical CO2

Coffee is the world’s second most widely traded commodity, following only petroleum. Across the globe, people love coffee’s aroma and taste. Many of us also depend on one component of coffee—caffeine—to help us get going in the morning or stay alert in the afternoon. But late in the day, coffee’s stimulant effect can keep you from sleeping, so you may choose to drink decaffeinated coffee in the evening.

Since the early 1900s, many methods have been used to decaffeinate coffee. All have advantages and disadvantages, and all depend on the physical and chemical properties of caffeine. Because caffeine is a somewhat polar molecule, it dissolves well in water, a polar liquid. However, since many of the other 400-plus compounds that contribute to coffee’s taste and aroma also dissolve in H2O, hot water decaffeination processes can also remove some of these compounds, adversely affecting the smell and taste of the decaffeinated coffee. Dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) and ethyl acetate (CH3CO2C2H5) have similar polarity to caffeine, and are therefore very effective solvents for caffeine extraction, but both also remove some flavour and aroma components, and their use requires long extraction and cleanup times. Because both of these solvents are toxic, health concerns have been raised regarding the effect of residual solvent remaining in the decaffeinated coffee.

Supercritical fluid extraction using carbon dioxide is now being widely used as a more effective and environmentally friendly decaffeination method (Figure 13.4f). At temperatures above 304.2 K and pressures above 7376 kPa, CO2 is a supercritical fluid, with properties of both gas and liquid. Like a gas, it penetrates deep into the coffee beans; like a liquid, it effectively dissolves certain substances. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of steamed coffee beans removes 97−99% of the caffeine, leaving coffee’s flavour and aroma compounds intact. Because CO2 is a gas under standard conditions, its removal from the extracted coffee beans is easily accomplished, as is the recovery of the caffeine from the extract. The caffeine recovered from coffee beans via this process is a valuable product that can be used subsequently as an additive to other foods or drugs.

Attribution & References

- At 0.3 kPa: [latex]\text{s}\;{\longrightarrow}\;\text{g}[/latex] at −58 °C. At 50 kPa: [latex]\text{s}\;{\longrightarrow}\;\text{l}[/latex] at 0 °C, [latex]\text{l}\;{\longrightarrow}\;\text{g}[/latex] at 78 °C ↵

-

at 1500 kPa: [latex]\text{s}\;{\longrightarrow}\;\text{l}[/latex] at −45 °C, [latex]\text{l}\;{\longrightarrow}\;\text{g}[/latex] at −10 °C;

at 500 kPa: [latex]\text{s}\;{\longrightarrow}\;\text{g}[/latex] at −58 °C

↵ - The critical temperature of ammonia is 405.5 K, which is higher than room temperature. The critical temperature of oxygen is below room temperature; thus oxygen cannot be liquefied at room temperature. ↵

pressure-temperature graph summarizing conditions under which the phases of a substance can exist

temperature and pressure at which the vapor, liquid, and solid phases of a substance are in equilibrium

substance at a temperature and pressure higher than its critical point; exhibits properties intermediate between those of gaseous and liquid states

temperature and pressure above which a gas cannot be condensed into a liquid