11.6 Molecular Structure and Polarity

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Predict the structures of small molecules using valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory

- Explain the concepts of polar covalent bonds and molecular polarity

- Assess the polarity of a molecule based on its bonding and structure

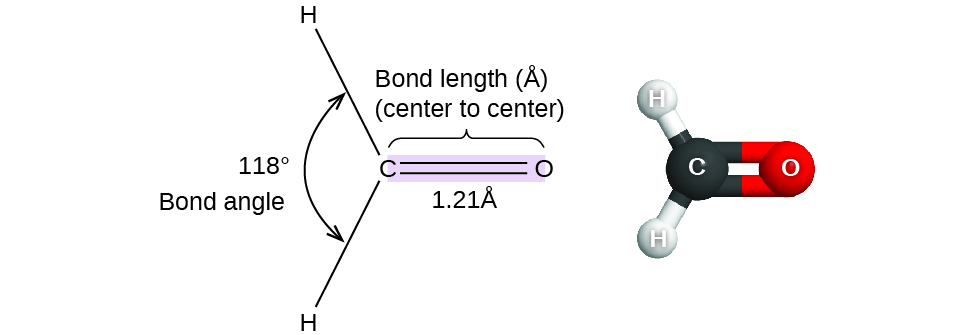

Thus far, we have used two-dimensional Lewis structures to represent molecules. However, the molecular structure is actually three-dimensional, and it is important to be able to describe molecular bonds in terms of their distances, angles, and relative arrangements in space (Figure 11.6a). A bond angle is the angle between any two bonds that include a common atom, usually measured in degrees. A bond distance (or bond length) is the distance between the nuclei of two bonded atoms along the straight line joining the nuclei. Bond distances are measured in Ångstroms (1 Å = 10–10 m) or picometers (1 pm = 10–12 m, 100 pm = 1 Å).

VSEPR Theory

Watch What is the shape of a molecule? (3:47 min)

Video source: TED-Ed. (2013, October 17). What is the shape of a molecule? - George Zaiden and Charles Morton [Video]. YouTube.

Valence shell electron-pair repulsion theory (VSEPR theory) enables us to predict the molecular structure, including approximate bond angles around a central atom, of a molecule from an examination of the number of bonds and lone electron pairs in its Lewis structure. The VSEPR model assumes that electron pairs in the valence shell of a central atom will adopt an arrangement that minimizes repulsions between these electron pairs by maximizing the distance between them. The electrons in the valence shell of a central atom form either bonding pairs of electrons, located primarily between bonded atoms, or lone pairs. The electrostatic repulsion of these electrons is reduced when the various regions of high electron density assume positions as far from each other as possible.

VSEPR theory predicts the arrangement of electron pairs around each central atom and, usually, the correct arrangement of atoms in a molecule. We should understand, however, that the theory only considers electron-pair repulsions. Other interactions, such as nuclear-nuclear repulsions and nuclear-electron attractions, are also involved in the final arrangement that atoms adopt in a particular molecular structure.

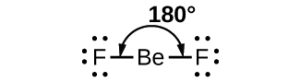

As a simple example of VSEPR theory, let us predict the structure of a gaseous BeF2 molecule. The Lewis structure of BeF2 (Figure 11.6b) shows only two electron pairs around the central beryllium atom. With two bonds and no lone pairs of electrons on the central atom, the bonds are as far apart as possible, and the electrostatic repulsion between these regions of high electron density is reduced to a minimum when they are on opposite sides of the central atom. The bond angle is 180° (Figure 11.6b).

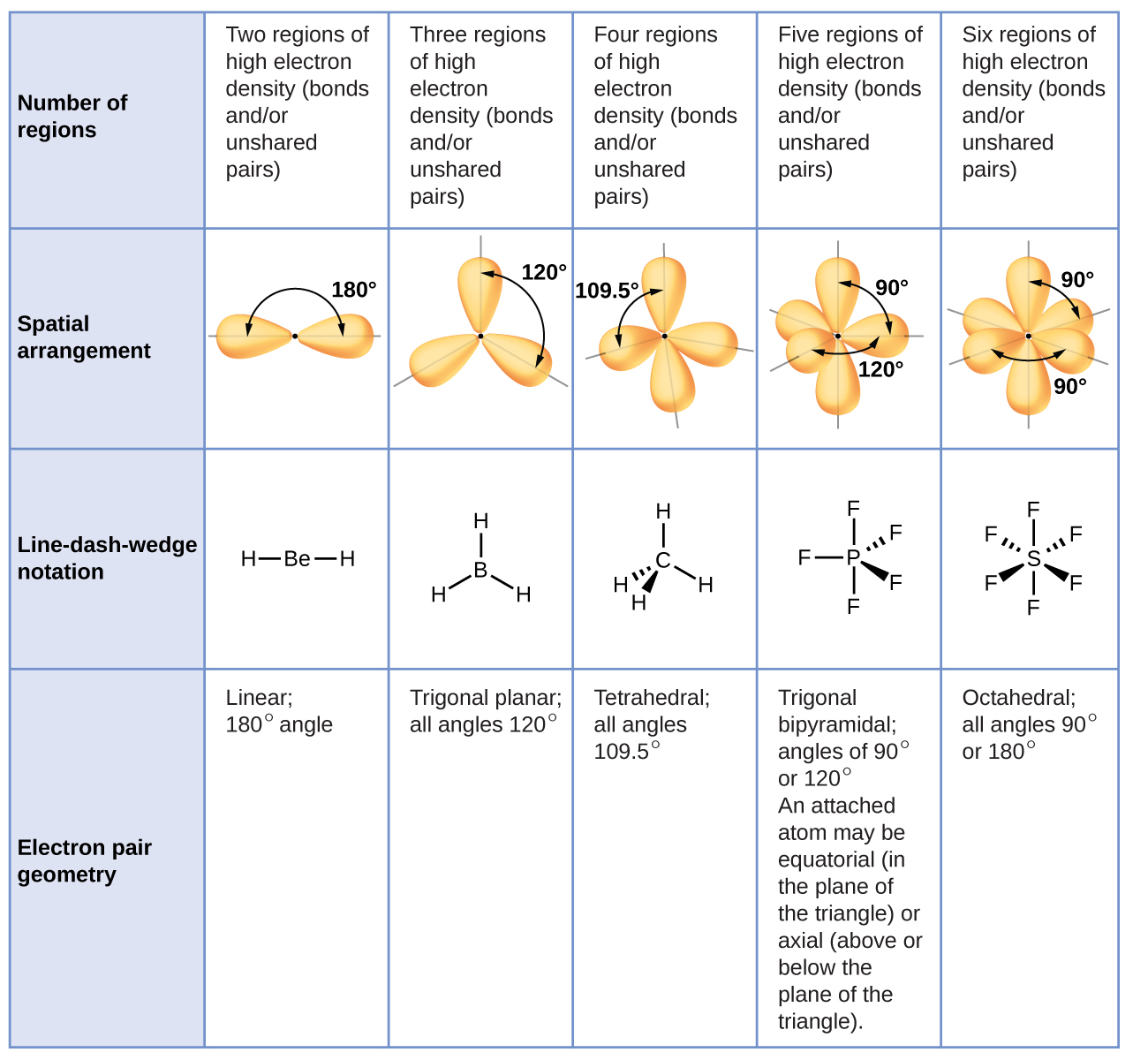

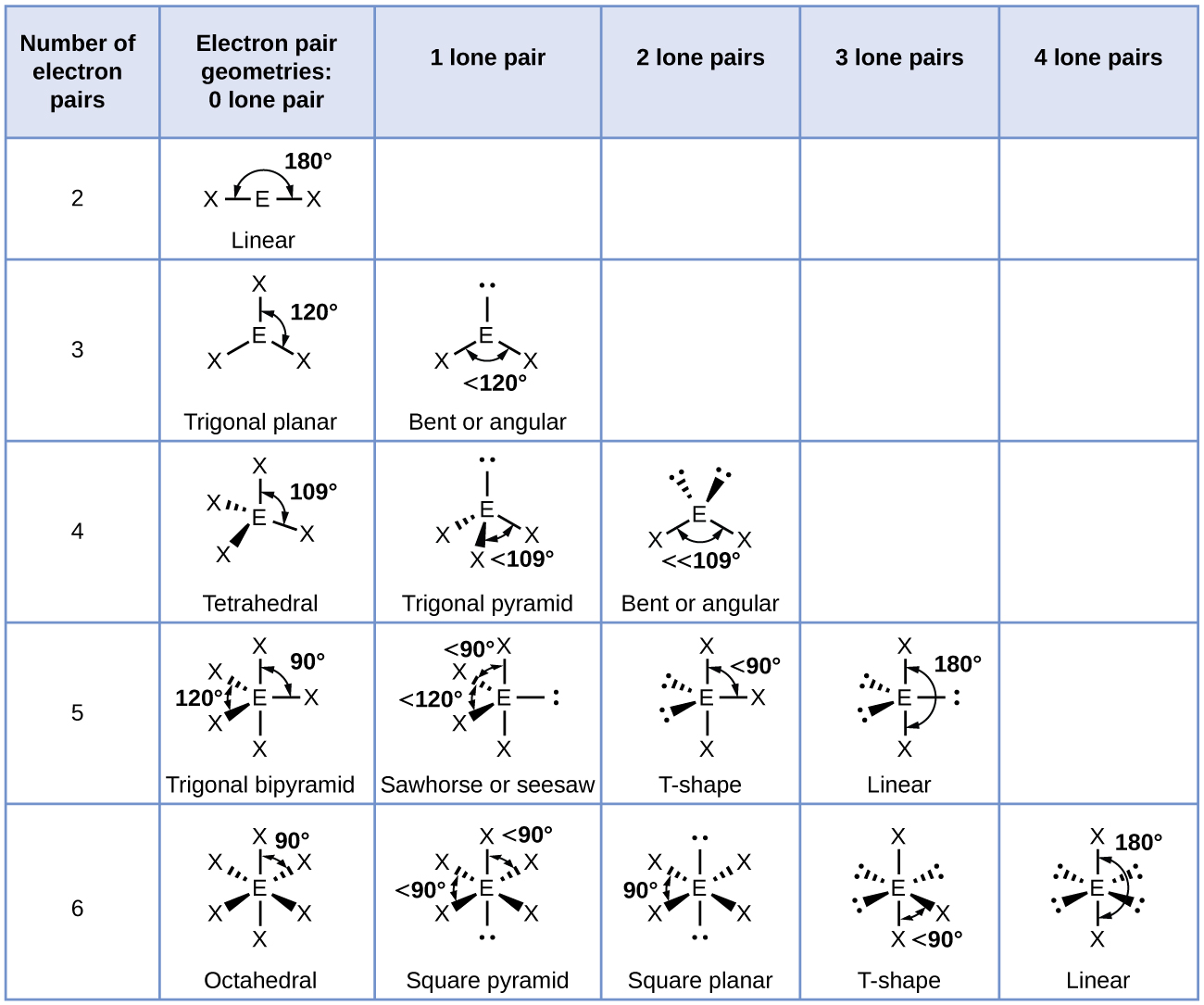

Figure 11.6c illustrates this and other electron-pair geometries that minimize the repulsions among regions of high electron density (bonds and/or lone pairs). Two regions of electron density around a central atom in a molecule form a linear geometry; three regions form a trigonal planar geometry; four regions form a tetrahedral geometry; five regions form a trigonal bipyramidal geometry; and six regions form an octahedral geometry.

Electron-pair Geometry versus Molecular Structure

It is important to note that electron-pair geometry around a central atom is not the same thing as its molecular structure. The electron-pair geometries shown in Figure 11.6c describe all regions where electrons are located, bonds as well as lone pairs. Molecular structure describes the location of the atoms, not the electrons.

We differentiate between these two situations by naming the geometry that includes all electron pairs the electron-pair geometry. The structure that includes only the placement of the atoms in the molecule is called the molecular structure. The electron-pair geometries will be the same as the molecular structures when there are no lone electron pairs around the central atom, but they will be different when there are lone pairs present on the central atom.

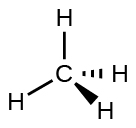

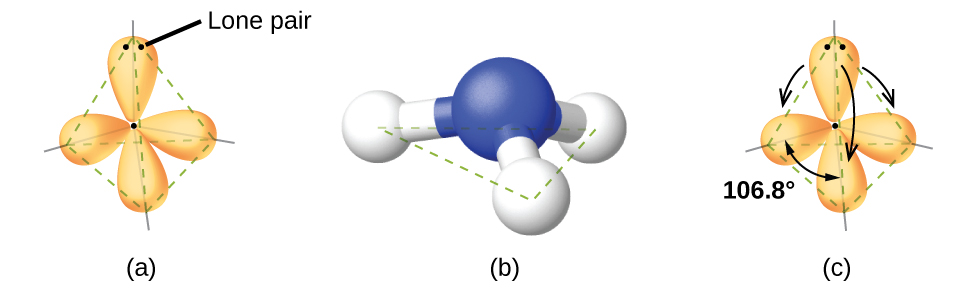

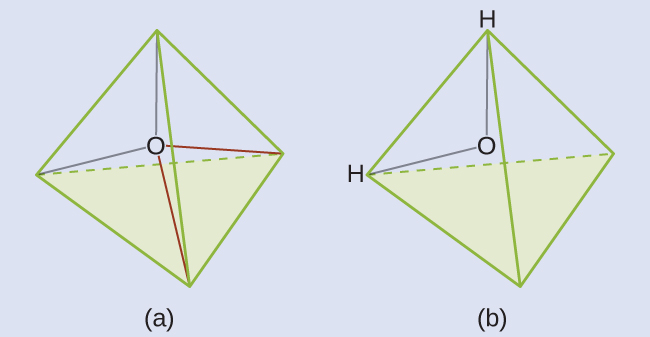

For example, the methane molecule, CH4, which is the major component of natural gas, has four bonding pairs of electrons around the central carbon atom; the electron-pair geometry is tetrahedral, as is the molecular structure (Figure 11.6d). On the other hand, the ammonia molecule, NH3, also has four electron pairs associated with the nitrogen atom, and thus has a tetrahedral electron-pair geometry. One of these regions, however, is a lone pair, which is not included in the molecular structure, and this lone pair influences the shape of the molecule (Figure 11.6e).

As seen in Figure 11.6e, small distortions from the ideal angles in Figure 11.6c can result from differences in repulsion between various regions of electron density. VSEPR theory predicts these distortions by establishing an order of repulsions and an order of the amount of space occupied by different kinds of electron pairs. The order of electron-pair repulsions from greatest to least repulsion is:

This order of repulsions determines the amount of space occupied by different regions of electrons. A lone pair of electrons occupies a larger region of space than the electrons in a triple bond; in turn, electrons in a triple bond occupy more space than those in a double bond, and so on. The order of sizes from largest to smallest is:

Consider formaldehyde, H2CO, which is used as a preservative for biological and anatomical specimens (Figure 11.6a). This molecule has regions of high electron density that consist of two single bonds and one double bond. The basic geometry is trigonal planar with 120° bond angles, but we see that the double bond causes slightly larger angles (121°), and the angle between the single bonds is slightly smaller (118°).

In the ammonia molecule, the three hydrogen atoms attached to the central nitrogen are not arranged in a flat, trigonal planar molecular structure, but rather in a three-dimensional trigonal pyramid (Figure 11.6e) with the nitrogen atom at the apex and the three hydrogen atoms forming the base. The ideal bond angles in a trigonal pyramid are based on the tetrahedral electron pair geometry. Again, there are slight deviations from the ideal because lone pairs occupy larger regions of space than do bonding electrons. The H–N–H bond angles in NH3 are slightly smaller than the 109.5° angle in a regular tetrahedron (Figure 11.6c) because the lone pair-bonding pair repulsion is greater than the bonding pair-bonding pair repulsion (Figure 11.6e). Figure 11.6f illustrates the ideal molecular structures, which are predicted based on the electron-pair geometries for various combinations of lone pairs and bonding pairs.

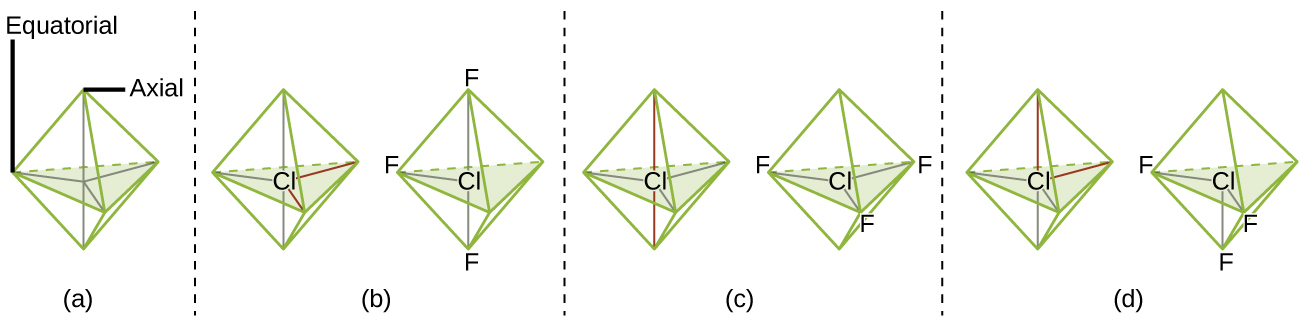

According to VSEPR theory, the terminal atom locations (Xs in Figure 11.6f) are equivalent within the linear, trigonal planar, and tetrahedral electron-pair geometries (the first three rows of the table). It does not matter which X is replaced with a lone pair because the molecules can be rotated to convert positions. For trigonal bipyramidal electron-pair geometries, however, there are two distinct X positions, as shown in Figure 11.6g: an axial position (if we hold a model of a trigonal bipyramid by the two axial positions, we have an axis around which we can rotate the model) and an equatorial position (three positions form an equator around the middle of the molecule). As shown in Figure 11.6f, the axial position is surrounded by bond angles of 90°, whereas the equatorial position has more space available because of the 120° bond angles. In a trigonal bipyramidal electron-pair geometry, lone pairs always occupy equatorial positions because these more spacious positions can more easily accommodate the larger lone pairs.

Theoretically, we can come up with three possible arrangements for the three bonds and two lone pairs for the ClF3 molecule (Figure 11.6g). The stable structure is the one that puts the lone pairs in equatorial locations, giving a T-shaped molecular structure.

When a central atom has two lone electron pairs and four bonding regions, we have an octahedral electron-pair geometry. The two lone pairs are on opposite sides of the octahedron (180° apart), giving a square planar molecular structure that minimizes lone pair-lone pair repulsions (Figure 11.6f).

Predicting Electron Pair Geometry and Molecular Structure

The following procedure uses VSEPR theory to determine the electron pair geometries and the molecular structures:

- Write the Lewis structure of the molecule or polyatomic ion.

- Count the number of regions of electron density (lone pairs and bonds) around the central atom. A single, double, or triple bond counts as one region of electron density.

- Identify the electron-pair geometry based on the number of regions of electron density: linear, trigonal planar, tetrahedral, trigonal bipyramidal, or octahedral (Figure 11.6f, first column).

- Use the number of lone pairs to determine the molecular structure (Figure 11.6f). If more than one arrangement of lone pairs and chemical bonds is possible, choose the one that will minimize repulsions, remembering that lone pairs occupy more space than multiple bonds, which occupy more space than single bonds. In trigonal bipyramidal arrangements, repulsion is minimized when every lone pair is in an equatorial position. In an octahedral arrangement with two lone pairs, repulsion is minimized when the lone pairs are on opposite sides of the central atom.

The following examples illustrate the use of VSEPR theory to predict the molecular structure of molecules or ions that have no lone pairs of electrons. In this case, the molecular structure is identical to the electron pair geometry.

Example 11.6a

Predicting Electron-pair Geometry and Molecular Structure: CO2 and BCl3

Predict the electron-pair geometry and molecular structure for each of the following:

- carbon dioxide, CO2, a molecule produced by the combustion of fossil fuels

- boron trichloride, BCl3, an important industrial chemical

Solution

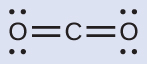

- We write the Lewis structure of CO2 as:

This shows us two regions of high electron density around the carbon atom—each double bond counts as one region, and there are no lone pairs on the carbon atom. Using VSEPR theory, we predict that the two regions of electron density arrange themselves on opposite sides of the central atom with a bond angle of 180°. The electron-pair geometry and molecular structure are identical, and CO2 molecules are linear.

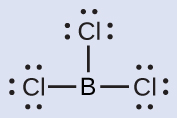

This shows us two regions of high electron density around the carbon atom—each double bond counts as one region, and there are no lone pairs on the carbon atom. Using VSEPR theory, we predict that the two regions of electron density arrange themselves on opposite sides of the central atom with a bond angle of 180°. The electron-pair geometry and molecular structure are identical, and CO2 molecules are linear. - We write the Lewis structure of BCl3 as:

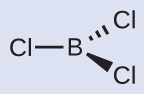

Thus we see that BCl3 contains three bonds, and there are no lone pairs of electrons on boron. The arrangement of three regions of high electron density gives a trigonal planar electron-pair geometry. The B–Cl bonds lie in a plane with 120° angles between them. BCl3 also has a trigonal planar molecular structure (Figure 11.6h).

Thus we see that BCl3 contains three bonds, and there are no lone pairs of electrons on boron. The arrangement of three regions of high electron density gives a trigonal planar electron-pair geometry. The B–Cl bonds lie in a plane with 120° angles between them. BCl3 also has a trigonal planar molecular structure (Figure 11.6h).

Figure 11.6h Trigonal planar molecule BCl3

The electron-pair geometry and molecular structure of BCl3 are both trigonal planar. Note that the VSEPR geometry indicates the correct bond angles (120°), unlike the Lewis structure shown above.

Exercise 11.6a

Carbonate, CO32−, is a common polyatomic ion found in various materials from eggshells to antacids. What are the electron-pair geometry and molecular structure of this polyatomic ion?

Check Your Answer[1]

Example 11.6b

Predicting Electron-pair Geometry and Molecular Structure: Ammonium

Two of the top 50 chemicals produced in the United States, ammonium nitrate and ammonium sulfate, both used as fertilizers, contain the ammonium ion. Predict the electron-pair geometry and molecular structure of the NH4+ cation.

Solution

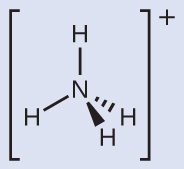

We write the Lewis structure of NH4+ as:

We can see that NH4+ contains four bonds from the nitrogen atom to hydrogen atoms and no lone pairs. We expect the four regions of high electron density to arrange themselves so that they point to the corners of a tetrahedron with the central nitrogen atom in the middle (Figure 11.6i). Therefore, the electron pair geometry of NH4+ is tetrahedral, and the molecular structure is also tetrahedral (Figure 11.6i).

Exercise 11.6b

Identify a molecule with a trigonal bipyramidal molecular structure.

Check Your Answer[2]

The next several examples illustrate the effect of lone pairs of electrons on molecular structure.

Example 11.6c

Predicting Electron-pair Geometry and Molecular Structure: Lone Pairs on the Central Atom

Predict the electron-pair geometry and molecular structure of a water molecule.

Solution

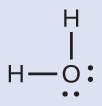

The Lewis structure of H2O indicates that there are four regions of high electron density around the oxygen atom: two lone pairs and two chemical bonds:

We predict that these four regions are arranged in a tetrahedral fashion (Figure 11.6j), as indicated in Figure 11.6e. Thus, the electron-pair geometry is tetrahedral and the molecular structure is bent with an angle slightly less than 109.5°. In fact, the bond angle is 104.5°.

Exercise 11.6c

The hydronium ion, H3O+, forms when acids are dissolved in water. Predict the electron-pair geometry and molecular structure of this cation.

Check Your Answer[3]

Example 11.6d

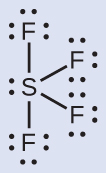

Predicting Electron-pair Geometry and Molecular Structure: SF4

Sulfur tetrafluoride, SF4, is extremely valuable for the preparation of fluorine-containing compounds used as herbicides (i.e., SF4 is used as a fluorinating agent). Predict the electron-pair geometry and molecular structure of an SF4 molecule.

Solution

The Lewis structure of SF4 indicates five regions of electron density around the sulfur atom: one lone pair and four bonding pairs:

We expect these five regions to adopt a trigonal bipyramidal electron-pair geometry. To minimize lone pair repulsions, the lone pair occupies one of the equatorial positions. The molecular structure (Figure 11.6k) is that of a seesaw (Figure 11.6k).

Exercise 11.6d

Predict the electron pair geometry and molecular structure for molecules of XeF2.

Check Your Answer[4]

Example 11.6e

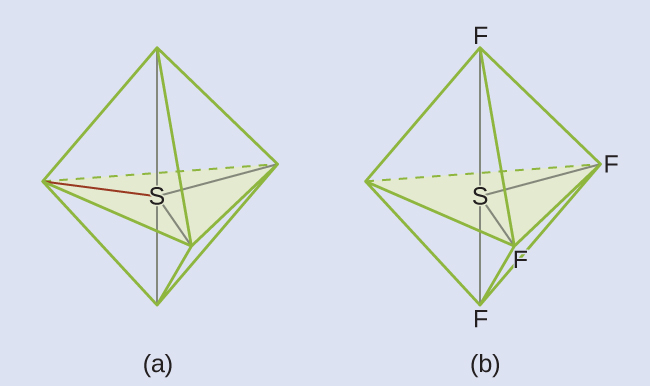

Predicting Electron-pair Geometry and Molecular Structure: XeF4

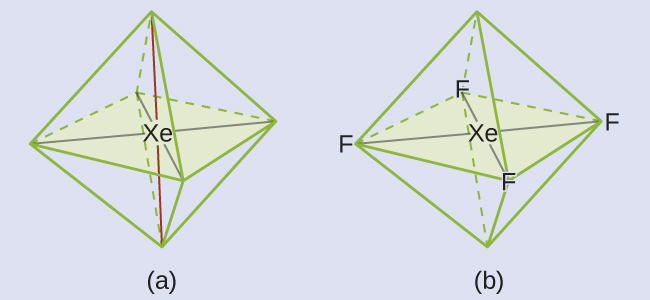

Of all the noble gases, xenon is the most reactive, frequently reacting with elements such as oxygen and fluorine. Predict the electron-pair geometry and molecular structure of the XeF4 molecule.

Solution

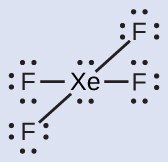

The Lewis structure of XeF4 indicates six regions of high electron density around the xenon atom: two lone pairs and four bonds:

These six regions adopt an octahedral arrangement (Figure 11.6l), which is the electron-pair geometry. To minimize repulsions, the lone pairs should be on opposite sides of the central atom (Figure 11.6l). The five atoms are all in the same plane and have a square planar molecular structure.

Exercise 11.6e

In a certain molecule, the central atom has three lone pairs and two bonds. What will the electron pair geometry and molecular structure be?

Check Your Answer[5]

Molecular Structure for Multicentre Molecules

When a molecule or polyatomic ion has only one central atom, the molecular structure completely describes the shape of the molecule. Larger molecules do not have a single central atom, but are connected by a chain of interior atoms that each possess a “local” geometry. The way these local structures are oriented with respect to each other also influences the molecular shape, but such considerations are largely beyond the scope of this introductory discussion. For our purposes, we will only focus on determining the local structures.

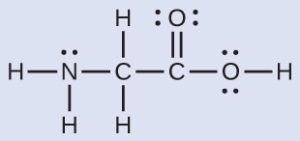

Example 11.6f

Predicting Structure in Multicentre Molecules

The Lewis structure for the simplest amino acid, glycine, H2NCH2CO2H, is shown here. Predict the local geometry for the nitrogen atom, the two carbon atoms, and the oxygen atom with a hydrogen atom attached:

Solution

Consider each central atom independently. The electron-pair geometries:

- nitrogen –– four regions of electron density; tetrahedral

- carbon in the CH2 group –– four regions of electron density; tetrahedral

- carbon in the CO2 group — three regions of electron density; trigonal planar

- oxygen in the OH group — four regions of electron density; tetrahedral

The local structures:

- nitrogen –– three bonds, one lone pair; trigonal pyramidal

- carbon in the CH2 group — four bonds, no lone pairs; tetrahedral

- carbon in the CO2 group — three bonds (double bond counts as one bond), no lone pairs; trigonal planar

- oxygen in the OH group — two bonds, two lone pairs; bent (109°)

Exercise 11.6f

Another amino acid is alanine, which has the Lewis structure shown here. Predict the electron-pair geometry and local structure of the nitrogen atom, the three carbon atoms, and the oxygen atom with hydrogen attached:

Check Your Answer[6]

Exercise 11.6g

Practice using the following PhET simulation Molecular Shapes:

Example 11.6g

Molecular Simulation

Use the molecular shape simulator in Exercise 11.6g. It allows us to control whether bond angles and/or lone pairs are displayed by checking or unchecking the boxes under “Options” on the right. We can also use the “Name” checkboxes at bottom-left to display or hide the electron pair geometry (called “electron geometry” in the simulator) and/or molecular structure (called “molecular shape” in the simulator).

Build the molecule HCN in the simulator based on the following Lewis structure:

Click on each bond type or lone pair at right to add that group to the central atom. Once you have the complete molecule, rotate it to examine the predicted molecular structure. What molecular structure is this?

Solution

The molecular structure is linear.

Exercise 11.6h

Build a more complex molecule in the simulator. Identify the electron-group geometry, molecular structure, and bond angles. Then try to find a chemical formula that would match the structure you have drawn.

Check Your Answer[7]

Molecular Polarity and Dipole Moment

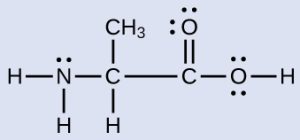

As discussed previously, polar covalent bonds connect two atoms with differing electronegativities, leaving one atom with a partial positive charge (δ+) and the other atom with a partial negative charge (δ–), as the electrons are pulled toward the more electronegative atom. This separation of charge gives rise to a bond dipole moment. The magnitude of a bond dipole moment is represented by the Greek letter mu (µ) and is given by the formula shown here, where Q is the magnitude of the partial charges (determined by the electronegativity difference) and r is the distance between the charges:

This bond moment can be represented as a vector, a quantity having both direction and magnitude (Figure 11.6m). Dipole vectors are shown as arrows pointing along the bond from the less electronegative atom toward the more electronegative atom. A small plus sign is drawn on the less electronegative end to indicate the partially positive end of the bond. The length of the arrow is proportional to the magnitude of the electronegativity difference between the two atoms.

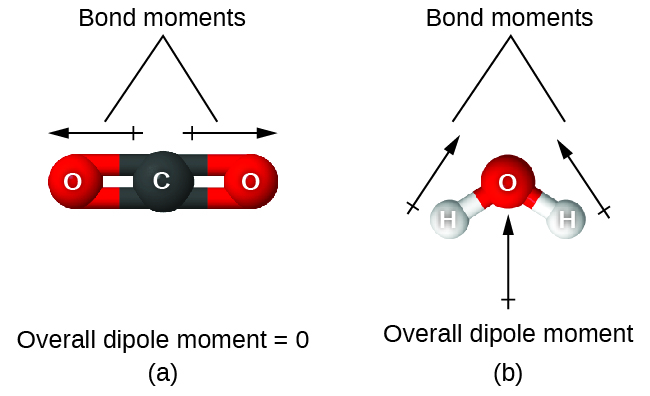

A whole molecule may also have a separation of charge, depending on its molecular structure and the polarity of each of its bonds. If such a charge separation exists, the molecule is said to be a polar molecule (or dipole); otherwise the molecule is said to be nonpolar. The dipole moment measures the extent of net charge separation in the molecule as a whole. We determine the dipole moment by adding the bond moments in three-dimensional space, taking into account the molecular structure.

For diatomic molecules, there is only one bond, so its bond dipole moment determines the molecular polarity. Homonuclear diatomic molecules such as Br2 and N2 have no difference in electronegativity, so their dipole moment is zero. For heteronuclear molecules such as CO, there is a small dipole moment. For HF, there is a larger dipole moment because there is a larger difference in electronegativity.

When a molecule contains more than one bond, the geometry must be taken into account. If the bonds in a molecule are arranged such that their bond moments cancel (vector sum equals zero), then the molecule is nonpolar. This is the situation in CO2 (Figure 11.6n). Each of the bonds is polar, but the molecule as a whole is nonpolar. From the Lewis structure, and using VSEPR theory, we determine that the CO2 molecule is linear with polar C=O bonds on opposite sides of the carbon atom. The bond moments cancel because they are pointed in opposite directions. In the case of the water molecule (Figure 11.6n), the Lewis structure again shows that there are two bonds to a central atom, and the electronegativity difference again shows that each of these bonds has a nonzero bond moment. In this case, however, the molecular structure is bent because of the lone pairs on O, and the two bond moments do not cancel. Therefore, water does have a net dipole moment and is a polar molecule (dipole).

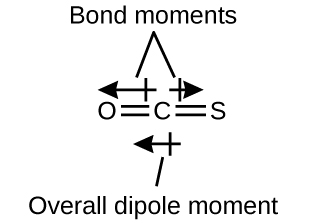

The OCS molecule (Figure 11.6o) has a structure similar to CO2, but a sulfur atom has replaced one of the oxygen atoms. To determine if this molecule is polar, we draw the molecular structure. VSEPR theory predicts a linear molecule:

The C-O bond is considerably polar. Although C and S have very similar electronegativity values, S is slightly more electronegative than C, and so the C-S bond is just slightly polar. Because oxygen is more electronegative than sulfur, the oxygen end of the molecule is the negative end.

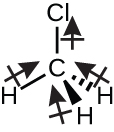

Chloromethane, CH3Cl (Figure 11.6p), is another example of a polar molecule. Although the polar C–Cl and C–H bonds are arranged in a tetrahedral geometry, the C–Cl bonds have a larger bond moment than the C–H bond, and the bond moments do not completely cancel each other. All of the dipoles have a downward component in the orientation shown, since carbon is more electronegative than hydrogen and less electronegative than chlorine:

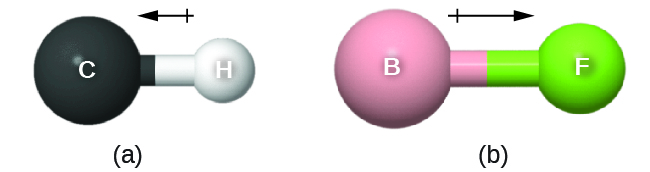

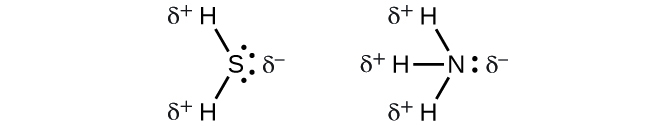

When we examine the highly symmetrical molecules BF3 (trigonal planar), CH4 (tetrahedral), PF5 (trigonal bipyramidal), and SF6 (octahedral), in which all the polar bonds are identical, the molecules are nonpolar. The bonds in these molecules are arranged such that their dipoles cancel. However, just because a molecule contains identical bonds does not mean that the dipoles will always cancel. Many molecules that have identical bonds and lone pairs on the central atoms have bond dipoles that do not cancel. Examples include H2S and NH3 (Figure 11.6q). A hydrogen atom is at the positive end and a nitrogen or sulfur atom is at the negative end of the polar bonds in these molecules:

To summarize, to be polar, a molecule must:

- Contain at least one polar covalent bond.

- Have a molecular structure such that the sum of the vectors of each bond dipole moment does not cancel.

Exercise 11.6i

Check Your Learning Exercise (Text Version)

From their positions in the periodic table, arrange the atoms in each of the following series in order of increasing electronegativity:

- C, F, H, N, O

- Br, Cl, F, H, I

- F, H, O, P, S

- Al, H, Na, O, P

- Ba, H, N, O, As

Check Your Answer[8]

Source: "Exercise 11.6i" is adapted from "Exercise 4.2-7" in General Chemistry 1 & 2, a derivative of Chemistry (Open Stax) by Paul Flowers, Klaus Theopold, Richard Langley & William R. Robinson, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

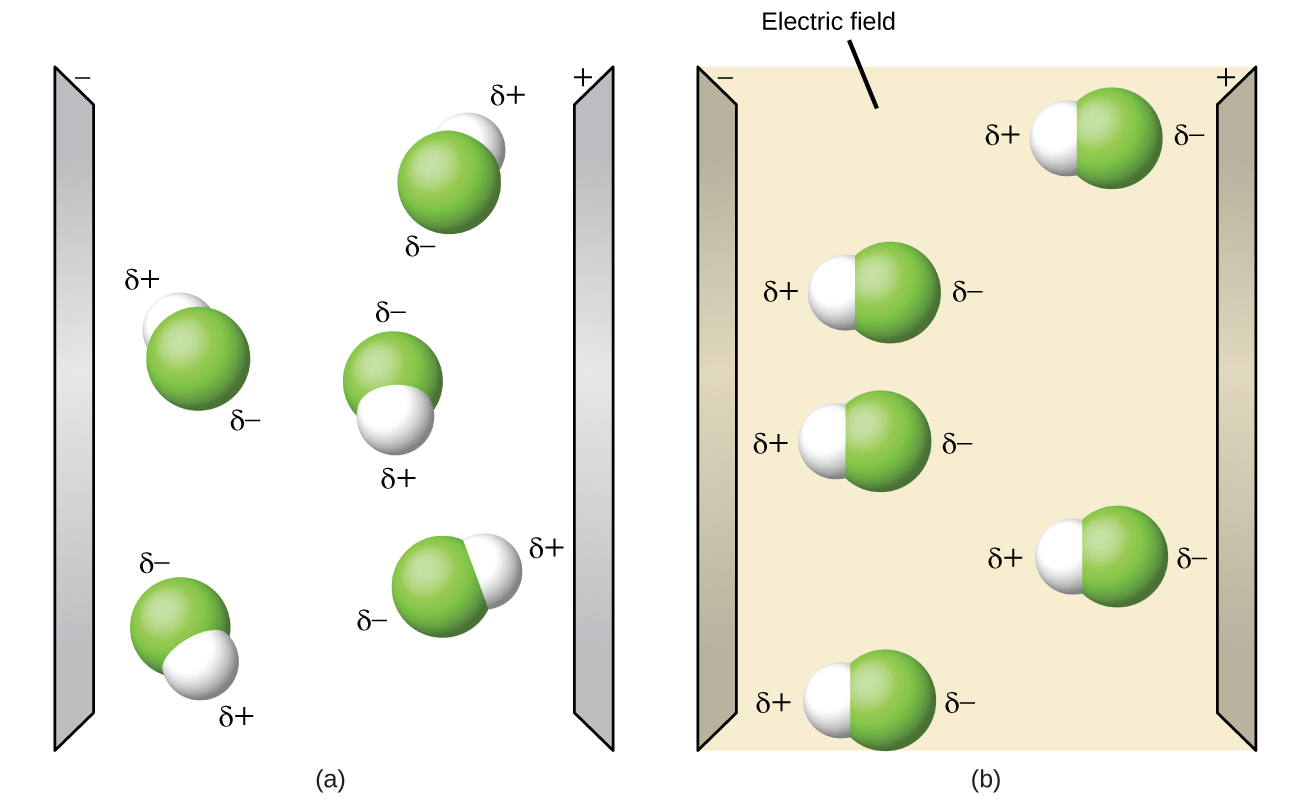

Properties of Polar Molecules

Polar molecules tend to align when placed in an electric field with the positive end of the molecule oriented toward the negative plate and the negative end toward the positive plate. We can use an electrically charged object to attract polar molecules, but nonpolar molecules are not attracted. Also, polar solvents are better at dissolving polar substances, and nonpolar solvents are better at dissolving nonpolar substances.

Exercise 11.6J

Practice using the following PhET simulation: Molecule Polarity.

Example 11.6h

Polarity Simulations

Open the molecule polarity simulation and select the “Three Atoms” tab at the top. This should display a molecule ABC with three electronegativity adjustors. You can display or hide the bond moments, molecular dipoles, and partial charges at the right. Turning on the Electric Field will show whether the molecule moves when exposed to a field, similar to Figure 11.6r.

Use the electronegativity controls to determine how the molecular dipole will look for the starting bent molecule if:

- A and C are very electronegative and B is in the middle of the range.

- A is very electronegative, and B and C are not.

Solution

- Molecular dipole moment points immediately between A and C.

- Molecular dipole moment points along the A–B bond, toward A.

Exercise 11.6K

Determine the partial charges that will give the largest possible bond dipoles.

Check Your Answer[9]

Links to Interactive Learning Tools

Explore VSEPR Theory from the Physics Classroom.

Attribution & References

- The electron-pair geometry is trigonal planar and the molecular structure is trigonal planar. Due to resonance, all three C–O bonds are identical. Whether they are single, double, or an average of the two, each bond counts as one region of electron density. ↵

- Any molecule with five electron pairs around the central atoms including no lone pairs will be trigonal bipyramidal. PF5 is a common example. ↵

- electron pair geometry: tetrahedral; molecular structure: trigonal pyramidal ↵

- The electron-pair geometry is trigonal bipyramidal. The molecular structure is linear. ↵

- electron pair geometry: trigonal bipyramidal; molecular structure: linear ↵

- electron-pair geometries: nitrogen––tetrahedral; carbon (CH)—tetrahedral; carbon (CH3)—tetrahedral; carbon (CO2)—trigonal planar; oxygen (OH)—tetrahedral; local structures: nitrogen—trigonal pyramidal; carbon (CH)—tetrahedral; carbon (CH3)—tetrahedral; carbon (CO2)—trigonal planar; oxygen (OH)—bent (109°) ↵

- Answers will vary. For example, an atom with four single bonds, a double bond, and a lone pair has an octahedral electron-group geometry and a square pyramidal molecular structure. XeOF4 is a molecule that adopts this structure. ↵

- (a) H, C, N, O, F; (b) H, I, Br, Cl, F; (c) H, P, S, O, F; (d) Na, Al, H, P, O; (e) Ba, H, As, N, O ↵

- The largest bond moments will occur with the largest partial charges. The two solutions above represent how unevenly the electrons are shared in the bond. The bond moments will be maximized when the electronegativity difference is greatest. The controls for A and C should be set to one extreme, and B should be set to the opposite extreme. Although the magnitude of the bond moment will not change based on whether B is the most electronegative or the least, the direction of the bond moment will. ↵

angle between any two covalent bonds that share a common atom

(also, bond length) distance between the nuclei of two bonded atoms

theory used to predict the bond angles in a molecule based on positioning regions of high electron density as far apart as possible to minimize electrostatic repulsion

shape in which two outside groups are placed on opposite sides of a central atom

shape in which three outside groups are placed in a flat triangle around a central atom with 120° angles between each pair and the central atom

shape in which four outside groups are placed around a central atom such that a three-dimensional shape is generated with four corners and 109.5° angles between each pair and the central atom

shape in which five outside groups are placed around a central atom such that three form a flat triangle with 120° angles between each pair and the central atom, and the other two form the apex of two pyramids, one above and one below the triangular plane

shape in which six outside groups are placed around a central atom such that a three-dimensional shape is generated with four groups forming a square and the other two forming the apex of two pyramids, one above and one below the square plane

arrangement around a central atom of all regions of electron density (bonds, lone pairs, or unpaired electrons)

structure that includes only the placement of the atoms in the molecule

location in a trigonal bipyramidal geometry in which there is another atom at a 180° angle and the equatorial positions are at a 90° angle

one of the three positions in a trigonal bipyramidal geometry with 120° angles between them; the axial positions are located at a 90° angle

separation of charge in a bond that depends on the difference in electronegativity and the bond distance represented by partial charges or a vector

quantity having magnitude and direction

(also, dipole) molecule with an overall dipole moment

property of a molecule that describes the separation of charge determined by the sum of the individual bond moments based on the molecular structure