2.1 Measurements

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand and apply fundamental measurements in scientific notation.

- Employ Systeme Internationale (SI) measurements

Scientific Notation

Scientific Notation is a method to simplify very large and very small numbers by utilizing a base 10 exponential methodology. The in above examples given 298 000 kg is equivalent to 2.98 × 10 × 10 × 10 × 10 × 10 × 10 or 2.98x105 whereas, 0.0000025 kilograms, is equivalent to 2.5 × 1/10 × 1/10 × 1/10 × 1/10 × 1/10 × 1/10 or 2.5 x 10−6 kg. Using a scientific calculator effectively can reduce the introduction of calculation errors. For example, 298 000 can be inputted as 2.98 [EXP] 5 as scientific notation of the former example.

Units

Units, such as litres, pounds, and centimetres, are standards of comparison for measurements. When we buy a 2-litre bottle of a soft drink, we expect that the volume of the drink was measured, so it is two times larger than the volume that everyone agrees to be 1 litre. The meat used to prepare a 0.25-pound hamburger is measured so it weighs one-fourth as much as 1 pound. Without units, a number can be meaningless, confusing, or possibly life threatening. Suppose a doctor prescribes phenobarbital to control a patient’s seizures and states a dosage of “100” without specifying units. Not only will this be confusing to the medical professional giving the dose, but the consequences can be dire: 100 mg given three times per day can be effective as an anticonvulsant, but a single dose of 100 g is more than 10 times the lethal amount.

We usually report the results of scientific measurements in SI units, an updated version of the metric system, using the units listed in Table 2.1a. Other units can be derived from these base units. The standards for these units are fixed by international agreement, and they are called the International System of Units or SI Units (from the French, Le Système International d’Unités). SI units have been used by the United States National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) since 1964.

| Property Measured | Name of Unit | Symbol of Unit |

|---|---|---|

| length | meter | m |

| mass | kilogram | kg |

| time | second | s |

| temperature | kelvin | K |

| electric current | ampere | A |

| amount of substance | mole | mol |

| luminous intensity | candela | cd |

Sometimes we use units that are fractions or multiples of a base unit. Ice cream is sold in quarts (a familiar, non-SI base unit), pints (0.5 quart), or gallons (4 quarts). We also use fractions or multiples of units in the SI system, but these fractions or multiples are always powers of 10. Fractional or multiple SI units are named using a prefix and the name of the base unit. For example, a length of 1000 meters is also called a kilometre because the prefix kilo means “one thousand,” which in scientific notation is 103 (1 kilometre = 1000 m = 103 m). The prefixes used and the powers to which 10 are raised are listed in Table 2.1b.

| Prefix | Symbol | Factor | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| femto | f | 10−15 | 1 femtosec ond (fs) = 1 × 10−15 s (0.000000000000001 s) |

| pico | p | 10−12 | 1 picometer (pm) = 1 × 10−12 m (0.000000000001 m) |

| nano | n | 10−9 | 4 nanograms (ng) = 4 × 10−9 g (0.000000004 g) |

| micro | µ | 10−6 | 1 microliter (μL) = 1 × 10−6 L (0.000001 L) |

| milli | m | 10−3 | 2 millimoles (mmol) = 2 × 10−3 mol (0.002 mol) |

| centi | c | 10−2 | 7 centimeters (cm) = 7 × 10−2 m (0.07 m) |

| deci | d | 10−1 | 1 deciliter (dL) = 1 × 10−1 L (0.1 L ) |

| kilo | k | 103 | 1 kilometer (km) = 1 × 103 m (1000 m) |

| mega | M | 106 | 3 megahertz (MHz) = 3 × 106 Hz (3,000,000 Hz) |

| giga | G | 109 | 8 gigayears (Gyr) = 8 × 109 yr (8,000,000,000 Gyr) |

| tera | T | 1012 | 5 terawatts (TW) = 5 × 1012 W (5,000,000,000,000 W) |

SI Base Units

The initial units of the metric system, which eventually evolved into the SI system, were established in France during the French Revolution. The original standards for the meter and the kilogram were adopted there in 1799 and eventually by other countries. This section introduces four of the SI base units commonly used in chemistry. Other SI units will be introduced in subsequent chapters.

Length

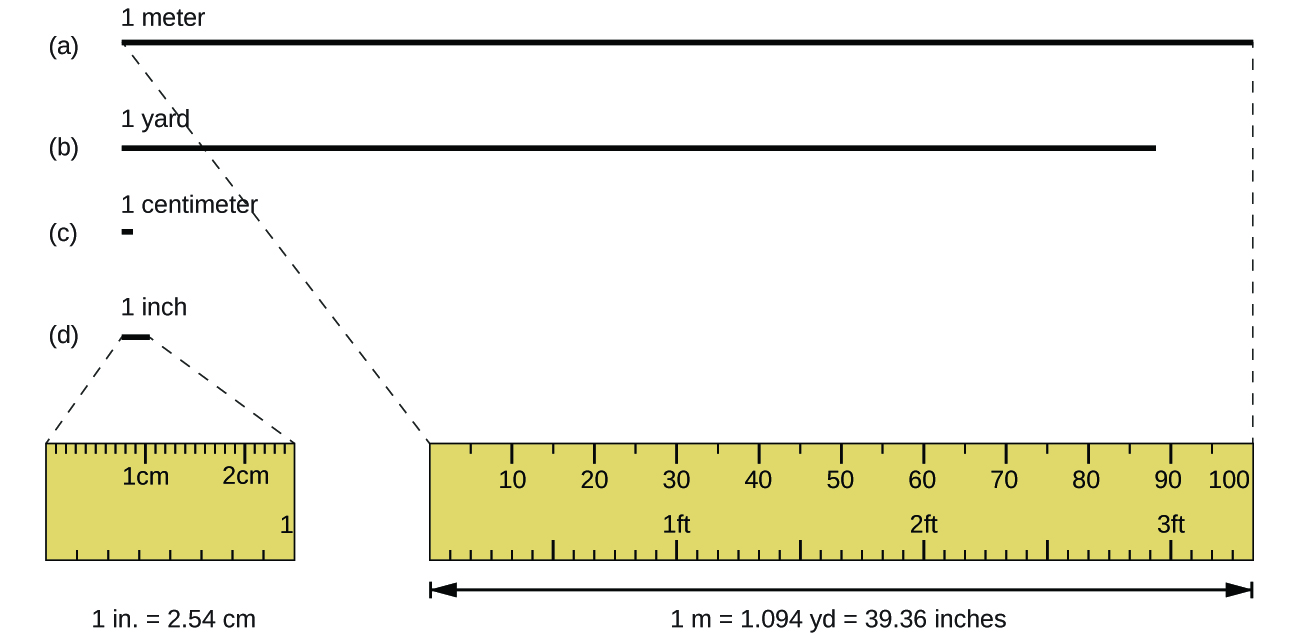

The standard unit of length in both the SI and original metric systems is the meter (m). A meter was originally specified as 1/10,000,000 of the distance from the North Pole to the equator. It is now defined as the distance light in a vacuum travels in 1/299,792,458 of a second. A meter is about 3 inches longer than a yard (Figure 2.1a); one meter is about 39.37 inches or 1.094 yards. Longer distances are often reported in kilometres (1 km = 1000 m = 103 m), whereas shorter distances can be reported in centimetres (1 cm = 0.01 m = 10−2 m) or millimetres (1 mm = 0.001 m = 10−3 m).

Mass

The standard unit of mass in the SI system is the kilogram (kg). A kilogram was originally defined as the mass of a litre of water (a cube of water with an edge length of exactly 0.1 meter). It is now defined by a certain cylinder of platinum-iridium alloy, which is kept in France (Figure 2.1b). Any object with the same mass as this cylinder is said to have a mass of 1 kilogram. One kilogram is about 2.2 pounds. The gram (g) is exactly equal to 1/1000 of the mass of the kilogram (10−3 kg).

Temperature

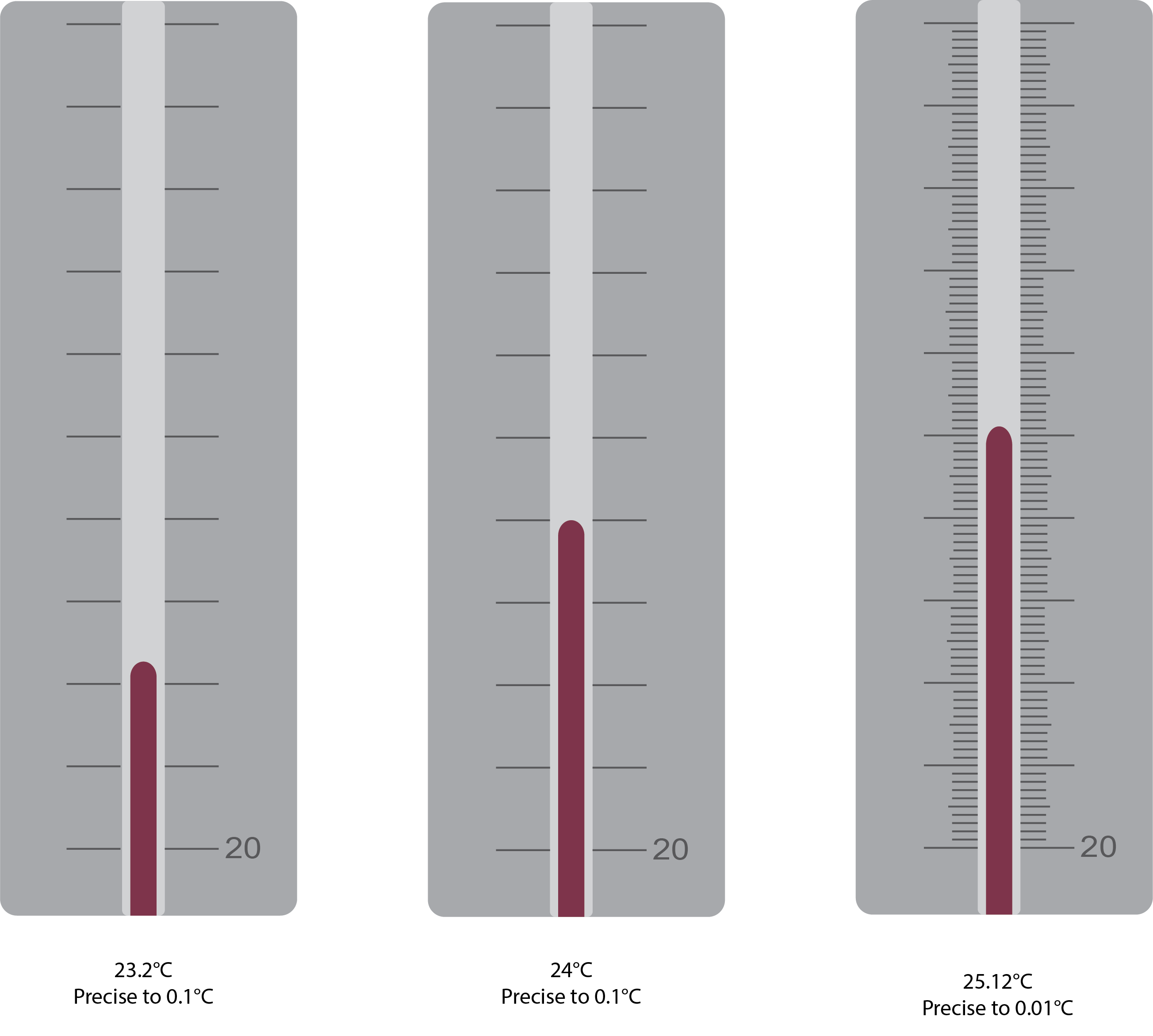

Temperature is an intensive property. The SI unit of temperature is the kelvin (K). The IUPAC convention is to use kelvin (all lowercase) for the word, K (uppercase) for the unit symbol, and neither the word “degree” nor the degree symbol (°). The degree Celsius (°C) is also allowed in the SI system, with both the word “degree” and the degree symbol used for Celsius measurements. Celsius degrees are the same magnitude as those of kelvin, but the two scales place their zeros in different places. Water freezes at 273.15 K (0 °C) and boils at 373.15 K (100 °C) by definition, and normal human body temperature is approximately 310 K (37 °C). The conversion between these two units and the Fahrenheit scale will be discussed later in this chapter. The degree of precision varies when measuring temperature (Figure 2.1c).

Time

The SI base unit of time is the second (s). Small and large time intervals can be expressed with the appropriate prefixes; for example, 3 microseconds = 0.000003 s = 3 × 10−6 and 5 megaseconds = 5,000,000 s = 5 × 106 s. Alternatively, hours, days, and years can be used.

Derived SI Units

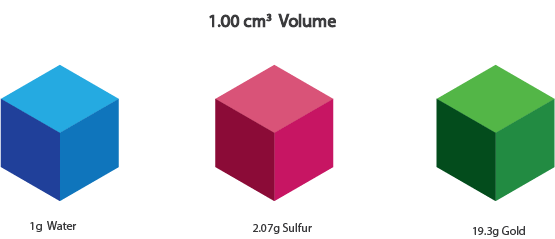

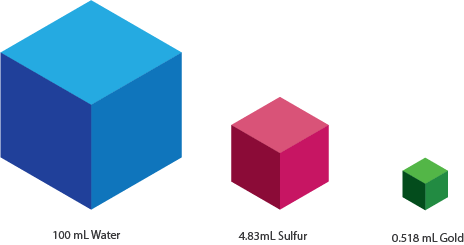

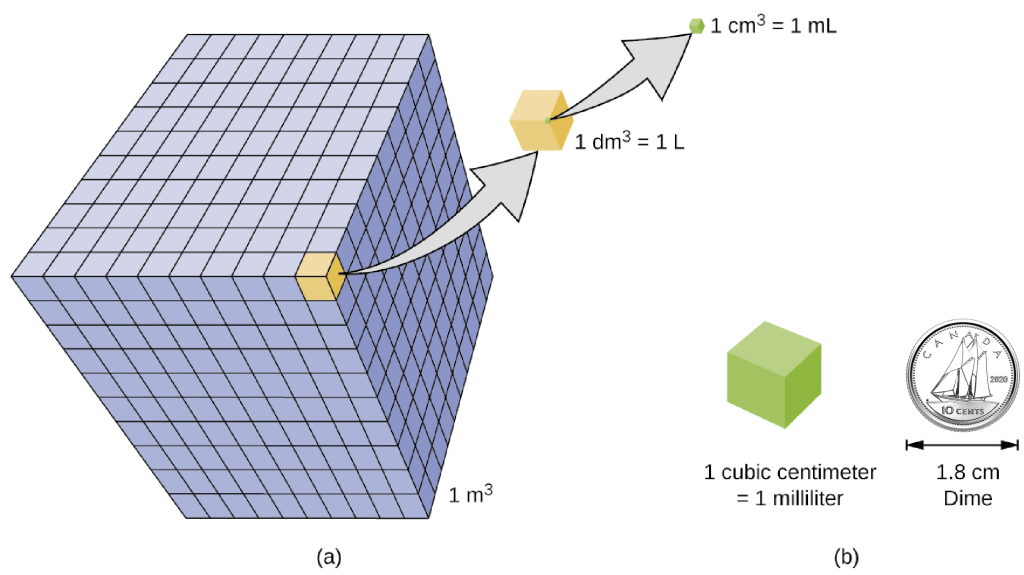

We can derive many units from the seven SI base units. For example, we can use the base unit of length to define a unit of volume, and the base units of mass and length to define a unit of density. Figures 2.1d and 2.1e demonstrate various volumes and masses of cubes.

Volume

Volume is the measure of the amount of space occupied by an object. The standard SI unit of volume is defined by the base unit of length (Figure 2.1f). The standard volume is a cubic meter (m3), a cube with an edge length of exactly one meter. To dispense a cubic meter of water, we could build a cubic box with edge lengths of exactly one meter. This box would hold a cubic meter of water or any other substance.

A more commonly used unit of volume is derived from the decimetre (0.1 m, or 10 cm). A cube with edge lengths of exactly one decimetre contains a volume of one cubic decimetre (dm3). A litre (L) is the more common name for the cubic decimetre. One litre is about 1.06 quarts. A cubic centimetre (cm3) is the volume of a cube with an edge length of exactly one centimetre. The abbreviation cc (for cubic centimetre) is often used by health professionals. A cubic centimetre is also called a millilitre (mL) and is 1/1000 of a litre.

Density

We use the mass and volume of a substance to determine its density. Thus, the units of density are defined by the base units of mass and length.

The density of a substance is the ratio of the mass of a sample of the substance to its volume. The SI unit for density is the kilogram per cubic meter (kg/m3). For many situations, however, this as an inconvenient unit, and we often use grams per cubic centimetre (g/cm3) for the densities of solids and liquids, and grams per litre (g/L) for gases. Although there are exceptions, most liquids and solids have densities that range from about 0.7 g/cm3 (the density of gasoline) to 19 g/cm3 (the density of gold). The density of air is about 1.2 g/L. Table 2.1c shows the densities of some common substances.

| Solids | Liquids | Gases (at 25 °C and 1 atm) |

|---|---|---|

| ice (at 0 °C) 0.92 g/cm3 | water 1.0 g/cm3 | dry air 1.20 g/L |

| oak (wood) 0.60–0.90 g/cm3 | ethanol 0.79 g/cm3 | oxygen 1.31 g/L |

| iron 7.9 g/cm3 | acetone 0.79 g/cm3 | nitrogen 1.14 g/L |

| copper 9.0 g/cm3 | glycerin 1.26 g/cm3 | carbon dioxide 1.80 g/L |

| lead 11.3 g/cm3 | olive oil 0.92 g/cm3 | helium 0.16 g/L |

| silver 10.5 g/cm3 | gasoline 0.70–0.77 g/cm3 | neon 0.83 g/L |

| gold 19.3 g/cm3 | mercury 13.6 g/cm3 | radon 9.1 g/L |

While there are many ways to determine the density of an object, perhaps the most straightforward method involves separately finding the mass and volume of the object and then dividing the mass of the sample by its volume. In the following example, the mass is found directly by weighing, but the volume is found indirectly through length measurements.

[latex]\text{density}=\frac{\text{mass}}{\text{volume}}[/latex]

Watch How taking a bath led to Archimedes' principle - Mark Salata (3 mins)

Video source: TED-Ed. (2012, September 6). How taking a bath led to Archimedes’ principle - Mark Salata [Video]. YouTube.

Example 2.1a

Density of lead

Calculation of Density Gold—in bricks, bars, and coins—has been a form of currency for centuries. In order to swindle people into paying for a brick of gold without actually investing in a brick of gold, people have considered filling the centres of hollow gold bricks with lead to fool buyers into thinking that the entire brick is gold. It does not work: Lead is a dense substance, but its density is not as great as that of gold, 19.3 g/cm3. What is the density of lead if a cube of lead has an edge length of 2.00 cm and a mass of 90.7 g?

Solution

The density of a substance can be calculated by dividing its mass by its volume. The volume of a cube is calculated by cubing the edge length.

[latex]\text{volume of lead cube}=2.00\text{cm}\times2.00\text{cm}\times2.00\text{cm}=8.00\text{cm}^3[/latex]

[latex]\text{density}=\frac{\text{mass}}{\text{volume}}=\frac{90.7\text{g}}{8.00\text{cm}^3}=11.3\;\text{g}/\text{cm}^3[/latex]

(We will discuss the reason for rounding to the first decimal place in the next section.)

Exercise 2.1a

- To three decimal places, what is the volume of a cube (cm3) with an edge length of 0.843 cm?

- If the cube in part (a) is copper and has a mass of 5.34 g, what is the density of copper to two decimal places?

Check Your Answer[1]

Example 2.1b

Displacement of water to determine density.

The simulation uses the displacement of water to determine the density. In the Compare section, determine the density of the red and yellow blocks.

Practice using the following PhET simulation: Density

Solution

When you open the density simulation and select Same Mass, you can choose from several 5.00-kg coloured blocks that you can drop into a tank containing 100.00 L water. The yellow block floats (it is less dense than water), and the water level rises to 105.00 L. While floating, the yellow block displaces 5.00 L water, an amount equal to the weight of the block. The red block sinks (it is more dense than water, which has density = 1.00 kg/L), and the water level rises to 101.25 L.

The red block therefore displaces 1.25 L water, an amount equal to the volume of the block. The density of the red block is:

[latex]{density=\dfrac{mass}{volume}=\dfrac{5.00\: kg}{1.25\: L}=4.00\: kg/L} \nonumber[/latex]

Note that since the yellow block is not completely submerged, you cannot determine its density from this information. But if you hold the yellow block on the bottom of the tank, the water level rises to 110.00 L, which means that it now displaces 10.00 L water, and its density can be found:

[latex]{density=\dfrac{mass}{volume}=\dfrac{5.00\: kg}{10.00\: L}=0.500\: kg/L} \nonumber[/latex]

Exercise 2.1b

Using the PhET Density simulation in Example 2.1b, remove all of the blocks from the water and add the green block to the tank of water, placing it approximately in the middle of the tank. Determine the density of the green block.

Check Your Answer[2]

Exercise 2.1c

Check Your Learning Exercise (Text Version)

For each of the following seven options (a-g), choose an SI base unit or derived unit from the word list that is appropriate for each given measurement:

Word List:

cubic millimeters, kilogram per cubic meter, degree Celsius, kilometer, meter per second, kilograms, square meters.

- The mass of the moon

- The distance from Vancouver to Toronto

- The speed of sound

- The density of air

- The temperature at which alcohol boils

- The area of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador

- The volume of a flu shot or a measles vaccination

Check Your Answer[3]

Source: "Exercise 2.1c" is adapted from "Exercise 1.4-4" from General Chemistry 1 & 2, a derivative of Chemistry (Open Stax) by Paul Flowers, Klaus Theopold, Richard Langley & William R. Robinson, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Links to Interactive Learning Tools

Explore various units of measurement and scientific notation in Measurement and Numbers from the Physics Classroom.

Practice Scientific Notation Identification from eCampusOntario H5P Studio.

Practice Density Calculation #1 from eCampusOntario H5P Studio.

Practice Density Calculation #2 from eCampusOntario H5P Studio.

Key Equations

- [latex]\text{density}=\frac{\text{mass}}{\text{volume}}[/latex]

Attribution & References

Except where otherwise noted, this page is adapted by JR van Haarlem and Samantha Sullivan Sauer from “1.4 Measurements”, In CHEM 2100: General Chemistry I (Mink) by CSU San Bernardino. / A derivative of Chemistry 2e (Open Stax) by Paul Flowers, Klaus Theopold, Richard Langley & William R. Robinson is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at Chemistry 2e (OpenStax) . / Learning objectives updated, custom graphics added.

method to simplify very large and very small numbers by utilizing a base 10 exponential methodology

Sandard of comparison for measurements

Amount of space occupied by an object

Standards fixed by international agreement in the International System of Units (Le Système International d’Unités)

Measure of one dimension of an object

Standard metric and SI unit of length; 1 m = approximately 1.094 yards

Standard SI unit of mass; 1 kg = approximately 2.2 pounds

SI unit of temperature; 273.15 K = 0 ºC

Unit of temperature; water freezes at 0 °C and boils at 100 °C on this scale.

Standards fixed by international agreement in the International System of Units (Le Système International d’Unités)

SI unit of volume.

Also known as cubic decimeter. Unit of volume; 1 L = 1,000 cm3

Volume of a cube with an edge length of exactly 1 cm.

1/1,000 of a liter; equal to 1 cm3

Ratio of mass to volume for a substance or object.