Using Sources to Support Your Writing

Using Sources to Serve Academic Argument

At some point in your academic career, you will be asked to move beyond merely reporting on the findings of sources, as you would in a bibliography, and instead to use what you have learned from sources to participate meaningfully and responsibly in an academic conversation. This may be a literal conversation or one that takes place in writing as writers read and respond to one another.

All academic writers must show how what they know or what they claim connects with prior information or knowledge. This is true even when these scholars are presenting a new study or their own new findings. Sometimes, academic writers contribute to what we know or understand about a subject by presenting their own position, or argument, in an ongoing debate. At these times, they must use perspectives and information from others to support or provide evidence for that position. This is a skill that you will practice as a composition student.

Finding credible, relevant sources is only one part of the research process; effectively integrating those sources in the arrangement of an academic or argumentative essay is a different task requiring further close reading and critical thinking. This chapter highlights three skills of academic writers when they work with sources:

- Considering the different roles that sources can play in your argument;

- Synthesizing, or connecting information from multiple sources in unique ways;

- Providing context for your reader about each source and how it fits into your argument.

Roles that Sources Can Play

Good Research is a Process that Starts with Inquiry

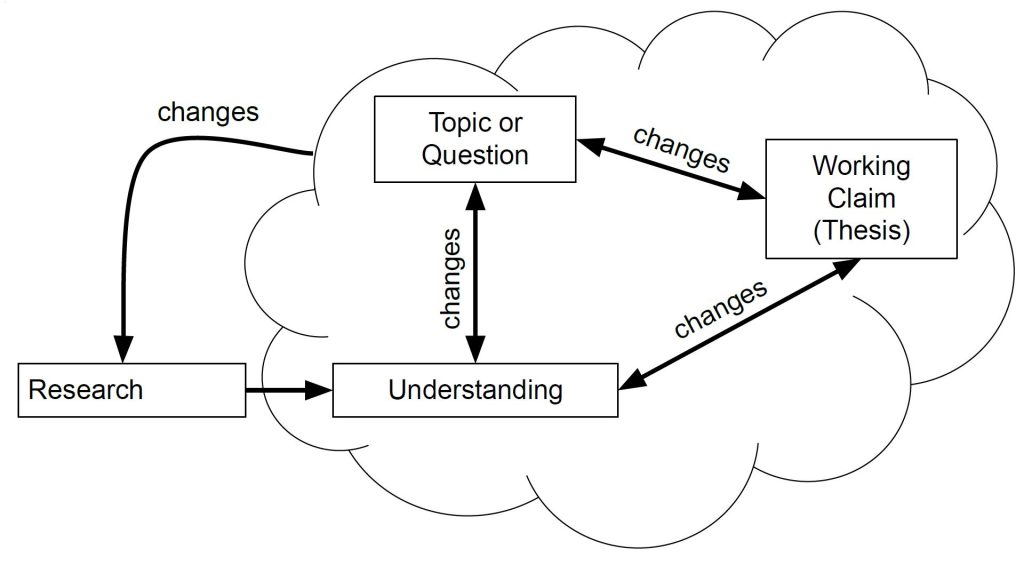

Good research starts with a question; you have an idea about something, and you want to learn more. Academic research is a specific type that involves finding and reading sources to prepare to participate in an academic conversation. This requires you to keep three elements in your mind and to stay aware of how they are changing, and how they are changing each other, as you learn more (figure 1):

- your central research topic or question

- your knowledge or understanding about the topic

- your working main claim or position about the topic (working thesis)

To evaluate whether a source is relevant for your purpose, you should not just try to decide whether it “fits” or relates to what you already know or believe. In fact, that source’s perspective may change what you believe. Or it may change your entire question or topic itself, as you learn about specific issues, conversations, and debates related to the question that you started with.

Example of Research as a Recursive Process

Imagine you start with a broad research question: “Are the graduation rates really so low for college students in the United States?” After some preliminary research, you learn that, yes, there are some statistics that highlight a problem of students starting but not finishing college.

So, you narrow your research question to learn more: “What factors contribute to students’ struggles with completing college?” And you start to see that there is an ongoing conversation about students from under-served populations: low-income students and first-generation students in particular.

So, given all your findings, you write a working thesis that might sound like this:

The promise of college as a gateway to increased financial earnings or lifelong success for its attendees isn’t panning out; more needs to be done to address completion rates for college graduates—especially among under-served populations, including students from low-income households.

Remember: your initial topic was graduation rates, and that shifted to a topic about why students struggle to finish college. While you are researching, keep in mind that the many ongoing conversations about higher education might not immediately “match” or sound just like your own search terms or topic. So, skimming articles and texts about your overarching topic—college—can still be valuable. Look at the article, “Is a tuition-free policy enough to ensure college success?” [New Tab] in figure 2 and note the title: it seems to be asking about the possible effects of free college tuition. It doesn’t look like it will “answer” your research question, but it can still prove useful.

As you skim this source, you find that, as the title implies, these authors argue that making college free is not “enough to ensure college success” because low-income students face more complex struggles than just the difficulty of affording college. So, even though your working thesis does not directly relate to the main claim or thesis of this article, it contains relevant perspectives and evidence about your topic.

Similarly, if your working question or topic is why low-income students struggle in college, then the Postsecondary Pathways out of poverty: City University of New York accelerated study in associate programs and the case for national policy article in figure 3 may not seem to answer your question directly. Instead, it appears to be about why a New York college’s “accelerated” associate degree programs should be used as a good model for making a policy for the whole nation. But, if these authors are arguing that their college has made a successful “pathway out of poverty,” then maybe part of their article first describes the problem that you are researching (low-income student struggles) before arguing for their specific solution.

After reading these and other sources, you should revisit and revise your working claim or thesis statement to reflect all that you have learned and the likely position that you will take in your argument. Note the changes between this one and the previous example:

Because low-income students do not complete college at the same rate as their peers due to several “hidden” barriers, American community colleges should redesign the ways in which they educate and support students from low-income households in order to meet the goal of putting those students on the path to increased financial earnings and lifelong stability.

Rereading Sources with their Roles in Mind

Once you have reached the step of preparing to “join the conversation” with your own writing, review how all of the perspectives and information you have gathered relate or “speak to” your working thesis statement. How will you organize and present all that you have learned to your reader to persuade them effectively?

You are already familiar with the idea of a text appealing to readers by providing logical reasons, conveying credibility, and evoking an emotional response. So you can think of the perspectives and information from your sources as tools that strengthen these rhetorical appeals of your argument. But sources can serve in more specific ways, too.

Sources often provide evidence to support the claims within your argument. There are different kinds of evidence that are persuasive in different ways:

- Numerical data and statistics such as the results of scientific studies or surveys

- Expert testimony: the views and ideas of experts who support your claims

- Stories and anecdotes: specific examples that illustrate the real human experience of your topic and elicit emotion

- Counterarguments: opposing viewpoints or ideas that otherwise challenge your claims, which you will refute or answer

Also, some sources may include background information that you must provide as a writer so that your reader is adequately informed about your topic. This may include:

- The scope or scale of your topic (where your topic is relevant and how widespread it is)

- Definitions of terms or explanations of unfamiliar concepts that are important to your argument

- The history of events that your reader must understand for a full understanding of why the topic exists in its present form

- Information that shows the timeliness or relevance of the issue (kairos) and why it is important right now

With all of your research available, it may help to check for gaps in your supporting evidence using a chart like the one in table 1.

| Type of source | Examples |

|---|---|

| Background/Kairos | Section 1: rates of enrollment increasing, but graduation rates low

Section 3: discussion about need for support that goes beyond financial assistance and discussion about what kind of support helps |

| Numerical data and statistics | Section 1: statistics about college attendance

+ also “only three in five completed their bachelor’s degree within six years” (para. 2) + contrast between students from high-income families who completed (3/4) and students from low-income families (under half) Section 3: statistics about success in one program “61-75%” Section 4: increase in AA degree from 18-33% |

| Expert testimonies | Section 3: quote attributed to Dell Scholars program, students need “ongoing support and assistance to address all of the emotional, lifestyle, and financial challenges that may prevent scholars from completing college” (para. 20).

Section 4: Levin and Garcia explain cost/value of program |

| Stories and anecdotes | Section 2: Story about “Veronica” and her needs for childcare and additional financial guidance

Story about “Marcus” as a full-time student and also supporting a family |

| Counterarguments | Last 2 paragraphs address problem of “free tuition” as a solution to completion rates; possible counterargument to explore? |

This kind of graphic organizer lets you “see” how your research will (or will not) help you start to build and support your argument.

A successful academic argument will draw from multiple sources in a variety of ways. So to help you create your graphic organizer—and start outlining your argumentative body paragraphs—it’s important that you review your sources strategically to start seeing how they will serve you as a writer. Let’s take a look at an article we’ve used in some of our model paragraphs (in the next section of this chapter).

This is an article called, “Feet on Campus, Heart at Home: First-Generation College Students Struggle with Divided Identities,” and it’s written by Linda Banks-Santilli, a college professor. In our research, we were focusing on the struggles faced by students from low-income families, but Banks-Santilli notes that around 50 percent of first-generation students are low-income students, so this article seems relevant to our argument as well. When we reread Banks-Santilli, keeping the different roles sources can play in mind, we can add to our graphic organizer (Table 2):

| Type of Source | Examples |

|---|---|

| Background/Kairos | Defines first-gen students, could use this in a separate paragraph about this population or explain that “About 50% of all FG students in the US are low-income” (para. 5). |

| Numerical data and statistics | |

| Expert testimonies | |

| Stories and anecdotes | Section 3 – last paragraph: one student’s experience moving away to college and still helping parents with household finances |

| Counterarguments |

It’s clear that this source, Banks-Santilli, doesn’t “serve” many parts of our thesis. This is because the focus of the article isn’t aligned with the focus of our argument. That doesn’t mean it isn’t a useful source in the creation and composition of our argument.

In fact, if you fill out a graphic organizer with all of your sources, you will be able to “see” quite a bit about what you have and what you need to make and support your argument. You will notice if there is an obvious lack of evidence, for instance, or a lack of counterarguments. You will probably not use everything you note in your graphic organizer in your actual essay, but the act of rereading sources critically to note how they can serve your argument will help you.

How Body Paragraphs Serve a Thesis

Students are sometimes intimidated by the prospect of a 6, 7, or even 10-page assignment. They can’t imagine they’ll have enough to say to fill that length. One way that may help tackle such a task is to consider a shift in your thinking: you’re no longer the researcher, you’re now the messenger, writing your own argument that explains and develops your thesis.

If we break down the thesis statement above we can see that there are several points to explain, claims to prove, and ideas to develop (Table 3), and these different parts will likely become different sections of your essay.

| Excerpt from thesis statement | Implications for body paragraphs |

|---|---|

| Because low-income students do not complete college at the same rate as their peers | First, this needs to be proven or demonstrated thoroughly to engage readers and prepare them for the rest of the argument. |

| due to several “hidden” barriers | The second half of this clause argues for the main cause of the problem—though it is not specified in detail—and this also needs to be explained and proven: what are the “hidden” barriers? What do readers need to know or understand regarding these obstacles to completion? What is the proof that these are the primary cause of the problem? |

| American community colleges should redesign the ways in which they educate and support students from low-income households in order to meet the goal of putting those students on the path to increased financial earnings and lifelong stability | This thesis ends with a “proposal” section: a call for change. It may be more complicated to support this:

Note: this thesis specifies community colleges, so the essay will likely focus on two-year institutions at some point in the argument. |

Check Your Understanding: Identifying parts of your working thesis

In your own paper, you may want to identify different points or parts of your working thesis. If you take the time to do this, you will be able to start imagining the different parts or sections of your own paper:

- Do you mention a specific problem? Will you prove that problem? Give background information about it? Define terms? Explore and discuss the current status of the problem?

- Should you address multiple causes of that problem? Or do you intend to demonstrate the severity of that problem by discussing effects?

- Have you identified multiple populations affected by the issue that you are presenting?

Once you’ve clarified (for yourself) what, exactly, you will need to accomplish in your essay to support your argument, you may find it easier to start drafting paragraphs that address those separate points. In fact, it can be most effective to write a draft of your body paragraphs before revising your thesis statement and finally drafting your introduction and conclusion sections.

Synthesis of Multiple Sources

One way in which academic writers create knowledge or make progress in the discussion or exploration of a topic is by juxtaposing or combining the ideas and perspectives from multiple sources, or synthesizing, in new ways.

When you write a summary, rhetorical analysis, or annotated bibliography, you are reporting on a single source at a time. Synthesis asks you to do more. Through research, you have reached a deeper understanding of the different perspectives or parts of your topic by reading multiple sources and finding connections between them. The goal of synthesis is to now try to help your reader to reach that same understanding. So synthesis is both the invisible act of learning about different perspectives and messages and the very visible act of using multiple sources in the composition of your own, unique message.

Why Synthesize?

Synthesis in academic writing helps your reader to see the same connections between information in sources that you see, which in turn helps to persuade your reader to reach the same conclusion that you have from your research.

Furthermore, your argument will be more well-rounded and more well-developed when you use more than one source of support for each of your main claims. Also, because it is often dangerous to rely on a single source for information, incorporating multiple sources in support of a claim or idea helps to ensure that your information is accurate to you and your reader.

Usually it is not considered productive for an academic writer to repeat, summarize, or paraphrase a large passage or many ideas from a single source. Not only does this fail to further the discussion of a topic beyond what has already been said by others, but it may also pose problems of academic integrity, since academic ethics require a writer to produce original work and provide attribution for ideas that are not their own.

Examples of Synthesis in a Sample Essay

A paragraph like the one below would appear earlier in the essay to provide background information as well as context, before the writer starts to “prove” the thesis. This is a meaningful way to engage readers and prepare them for the rest of the argument.

In this paragraph, the writer uses three sources to present the scope of the problem (essentially, the background information about the issue and some context about current data or ongoing discussions before highlighting the specific population of individuals that the thesis statement will address (students from low-income households). First, read the paragraph, then review Table 4 for annotations on how these sources are working together.

Students are not completing the college degrees they set out to achieve. The number of students attending college has increased over time; “In 1950, only 16 percent of young people had at least some college exposure. By 2012, this figure rose to 63 percent” (Page & Kehoe, 2016, para. 1). However, the rate of students graduating is just too low. According to NPR Education reporter Elissa Nadworny, “just 58 percent of students who started college in the fall of 2012 had earned any degree six years later” (Nadworny, 2019, para. 2). Nadworny (2019) is citing the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center for this information in her article written in 2019. Among community college students, this number is even lower: below forty percent (Nadworny, 2019). The promise of college as a way ahead is especially troubling for students who don’t come from a place of privilege. Statistics show that low-income students do not complete at the rate that) high-income students do (Page & Kehoe, 2019; Favero, 2018). In fact, researchers from the City University of New York published an article about an accelerated associate degree program aimed at helping increase graduation rates (Strumbos et al., 2018). They discuss the fact that college as a stepping stone or a way to advance students’ economic mobility becomes increasingly problematic when we recognize that students from low-income households are “six times less likely to have earned a bachelor’s degree by the age of twenty-five than those from high-income families” (Strumbos et al., 2018, p. 102). Page and Kehoe (2019) note that this is especially troubling since the “gaps in degree attainment” have been increasing (para. 3). Clearly this issue isn’t getting better on its own.

| excerpt from the paragraph | function of the the source(s) |

|---|---|

| The number of students attending college has increased over time; “In 1950, only 16 percent of young people had at least some college exposure. By 2012, this figure rose to 63 percent” (Page & Kehoe, 2019, para 1). However, the rate of students graduating is just too low. According to NPR Education reporter Elissa Nadworny (2019), “just 58 percent of students who started college in the fall of 2012 had earned any degree six years later” (para. 2). | One source shows the wider context of the total number of students attending college, and then other sources show the percentages of those students who actually graduate. |

| According to NPR Education reporter Elissa Nadworny (2019), “just 58 percent of students who started college in the fall of 2012 had earned any degree six years later” (para. 2). Nadworny is citing the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center for this information in her article written in 2019. Among community college students, this number is even lower: below forty percent (Nadworny, 2019) | The writer puts their topic in context by moving from general to specific. One source states the completion rates for American college students and then community college students. |

| They discuss the fact that college as a stepping stone or a way to advance students’ economic mobility becomes increasingly problematic when we recognize that students from low-income households are “six times less likely to have earned a bachelor’s degree by the age of twenty-five than those from high-income families” (Strumbos et al., 2018, p. 102). | Then, another source focuses more specifically on completion rates for low-income students. |

| Page and Kehoe (2019) note that this is especially troubling since the “gaps in degree attainment” have been increasing (para. 3). | This source claims that there is a trend, or consistent change over time. Proving that there is a growing problem shows the current relevance or timeliness (kairos) of the topic. |

A paragraph like the one below would serve as a body paragraph presenting one claim that supports our working thesis. This paragraph tries to engage readers logically, supporting its claim with evidence from sources. The first sentence acts as a topic sentence (a helpful indicator about the paragraph’s main claim). The writer then uses information from two sources to prove this claim. First, read the paragraph, then review Table 5 for annotations on how these sources are working together.

A major reason why low-income students do not earn degrees at the same rates as their peers is that they are more likely to face obstacles in their personal lives that may slow or delay their college progress. In their 2018 study, Strumbos et al. report that if a student does not complete twenty credits per year, they are not likely to complete their degree. Unfortunately, this “degree momentum” is often difficult for low-income students to achieve due to what Nathan Favero (2018), a professor of public policy at American University, calls “personal barriers to success.” For example, Favero notes that low-income students may be single parents who lack support from other family members, and so they “can feel a strong pull to pause their studies and start working” (Favero, 2018, para. 7) when unexpected bills arise. Diana Strumbos and her colleagues agree that “Work and family obligations sometimes force students to attend part time, which can again lead to a loss of momentum and decrease their likelihood of graduating” (Strumbos et al., 2018, p. 102). Therefore, typical degree programs and schedules often do not serve low-income students.

| excerpt from the paragraph | function of the the source(s) |

|---|---|

| if a student does not complete twenty credits per year, they are not likely to complete their degree. | The first source presents data to provide evidence (in this case, of the claim that pace of credits correlates with completion) |

| Unfortunately, this “degree momentum” is often difficult for low-income students to achieve due to what Nathan Favero, a professor of public policy at American University, calls “personal barriers to success.” | A different source is used here in order to show that multiple sources corroborate the claim. (Multiple experts have reached the same conclusion about a major cause of the problem.) |

| Favero notes that low-income students may be single parents who lack support from other family members, and so they “can feel a strong pull to pause their studies and start working” when unexpected bills arise. | The purpose of this evidence is to present an expert’s testimony or viewpoint. This expert view draws a conclusion or inference from the previously presented data, and it confirms the writer’s claim. |

| Diana Strumbos and her colleagues agree that “Work and family obligations sometimes force students to attend part time, which can again lead to a loss of momentum and decrease their likelihood of graduating.” | This source presents an expert view that affirms the main claim: the link between the cause (personal barriers) and the effect (loss of degree momentum). |

| Therefore, typical degree programs and schedules often do not serve low-income students. | The closing sentence reaches a new conclusion about the claim based on the evidence that has been presented. (In this example, because some students’ “personal barriers” are a cause of the problem, changes to “typical degree programs” may be part of the solution.) |

A paragraph like the one below would serve as a later body paragraph. This paragraph tries to engage the reader emotionally. After the writer has proven their claims about major causes of the issue by citing data that was reported by credible sources, the writer presents individual examples in narrative form—anecdotal evidence—to illustrate the quality or nature of the issue. First, read the paragraph, then review Table 6 for annotations on how these sources are working together.

It may be easy to overlook the role that a family plays in either supporting a student or creating additional burdens for them while at college. While time, money, and knowledge may flow from an affluent family to a student, for a low-income student it may be the other way around. For example, Linda Banks-Santilli, an Associate Professor of Education, explains how some first-generation students may feel as though they’re leaving their families behind or abandoning them. One student moved to live on campus, but she was concerned about her parents, who didn’t own or use computers, so she “divided her time,” Banks-Santilli notes, between her own coursework and paying her family’s bills (Banks-Santilli, 2015, para. 19). Page and Kehoe (2016) describe a similar situation when they introduce Marcus, a student who had “transitioned successfully to college but retained responsibility for supporting his family financially. […] Marcus stumbled academically, was placed on probation, and lost his financial aid” (para. 16). What Page and Kehoe (2016) demonstrate here is that playing the dual roles of student and family provider often proves too challenging to sustain.

| excerpt from the paragraph | function of the the source(s) |

|---|---|

| One student moved to live on campus, but she was concerned about her parents, who didn’t own or use computers, so she “divided her time,” Banks-Santilli notes, between her own coursework and paying her family’s bills (Banks-Santilli, 2015, para. 19). Page and Kehoe (2016) describe a similar situation when they introduce Marcus, a student who had “transitioned successfully to college but retained responsibility for supporting his family financially (para. 16). | Use of different sources suggests that these example situations are widespread, present in multiple contexts, or observed by multiple experts. |

| “[…] Marcus stumbled academically, was placed on probation, and lost his financial aid” (para. 16). | Multiple examples prompt the reader to find similarities between them and infer a pattern or trend. |

| that playing the dual roles of student and family provider often proves too challenging to sustain. | A phrase following the evidence states the common pattern or trend presented by multiple examples (“dual roles”) and states the claim that these examples support. The phrase reinforces the writer’s original claim (the burden of family obligations on low-income college students). |

Reviewing these annotations, you should see two things. First, that successful synthesis means that you have engaged in critical inquiry by drawing upon multiple texts and perspectives in order to form your own. Second, that the use of multiple sources can strengthen your argument by:

- showing how expert testimonies confirm data

- presenting common patterns or trends

- showing that an issue is present in multiple contexts

Check Your Understanding: Evaluating your paper draft, one paragraph at a time

Take an early draft of your paper and evaluate one paragraph at a time:

- How many sources have you cited in this paragraph?

- Do these sources “talk to each other”?

- What function(s) do these sources serve?

- Can you explain (to yourself) how each source has contributed to your overall message or perspective?

Putting Sources in Context

In general, you should refer to sources with your audience in mind. You should not expect your reader to infer the connection between your quotes, paraphrases, or summaries, and your claims. Nor should you simply drop quotes into your paragraphs without analyzing or discussing them in some way.

When revising a draft, you may find that you have dropped a quote into a paragraph with no introduction and then moved on without discussing the ideas of the quote at all. This is usually not helpful to academic readers. Or, you may find in your draft that you have repeated the phrase, “This quote says that…” or “This quote shows…” quite often. While this shows an effort to refer to quoted sources, it is not likely to help your reader to understand your sources or the specific ways in which they connect to your argument.

When you refer to a source in academic writing, you are taking it out of one context, where it was initially published, and transplanting it into another—your own writing, where it serves a specific purpose. Therefore, academic writers often include the most important information for their readers about:

- the original context of the source itself, and

- how the source information fits into their own argument

They often choose transitions that will best present this information in order to integrate source information into their writing.

Context of the Source Itself

When considering what your reader needs to know about the original context of source information, think about the five “w” questions (who, what, where, when, and why). Would explaining any of this information about the original source help your reader to understand the information and the role that it plays in your argument?

For example, in the body paragraph above, the writer writes:

Unfortunately, this “degree momentum” is often difficult for low-income students to achieve due to what Nathan Favero, a professor of public policy at American University, calls “personal barriers to success.”

This source serves the role of presenting an expert view agreeing with the writer’s claim, so the most relevant information about the source is who wrote it. Therefore, the paragraph introduces this evidence using a phrase that elaborates on the credentials of the author to show his expertise: “a professor of public policy at American University.” See table 7 for different ways to consider a source’s context.

| Information about the source’s original context | Consider explaining this in your writing when you want to show… |

|---|---|

| Who wrote it? | the author’s experience or credentials in order to present expert testimony, or show the unique perspective or bias of the source. |

| What is the author’s main idea or thesis? | how the source’s focus is different from or similar to your own. |

| Where was the source originally published? | the credibility of a source related to a specific topic or audience, or the bias of a source. |

| Where geographically was the information in the source gathered? | information about a different location or cultural context than the one you are writing about. |

| When was the source published? | past information, trends over time, contrasting information from different times, or relevance of current information (kairos). |

| Why was the source written, or why was the study conducted? | how a source’s purpose is different from or similar to your own.. |

| How did the author gather their information? | the significance or scope of numerical data or statistics, or how stories and anecdotes were gathered. |

You have probably heard of instances of dishonesty that occur when writers present information “out of context.” Sometimes, presenting source information without explaining its original purpose, audience, or context presents a false impression to your reader. In these cases, your writing may imply that a source agrees with, disagrees with, or relates to your claim when this is not the case.

Context of Your Argument

So how do you effectively integrate the words (quotes) and ideas (paraphrases) of your sources into your own argument?

First, keep in mind why you are quoting/paraphrasing a certain part of a certain source. Then, decide how you may need to refer to that source material in neighboring sentences in your own writing to help your reader to understand your intent and the role that this reference serves in your argument. Does the quote or paraphrase prove a claim that you have just made? Does it define or explain something that you are trying to make clear to readers? Does it provide an example or illustration of one of your claims? Does it elaborate on or introduce a different perspective about a previous point you have made?

Second, keeping your purpose for the quote or paraphrase in mind, choose the best transition words and phrases to show how the quote or paraphrase relates to the neighboring sentences and ideas.

- Transitions like Similarly or Furthermore will show that you are about to present more on a line of reasoning.

- Transitions like However or On the other hand will show that you are about to present a conflicting idea.

- Transitions like Consequently, Therefore, or Because will show cause and effect.

Third, choose the best signal verb to show how the source material relates to your neighboring sentences or ideas. These verbs, paired with the author of your source text, work much like transitional words and phrases.

If a reference is near the beginning of a paragraph or is the first reference to a source, you may choose a neutral verb:

- Favero (2018) writes that…

- Favero (2018) explores several factors that…

- Favero (2018) states/Favero (2018) argues

Later, you can connect source material to the ideas in your paragraph by using verbs that indicate how the source relates to neighboring ideas:

- show agreement (Favero (2018) concurs)

- disagreement (Favero (2018) disputes…)

You can also give readers an indication of what kind of information you will be presenting. Consider how these different verbs would fit with different types of quotations or paraphrases:

- Favero (2018) lists…

- Favero (2018) claims…

- Favero (2018) emphasizes…

Below, the sample body paragraph is shown, this time with key words highlighted to show how the writer integrates the source materials into the context of their own argument using transitions and signal verbs. Which highlighted words are most helpful to you as the reader, and what do they tell you about the writer’s purpose for each quote or paraphrase?

A major reason why low-income students do not earn degrees at the same rates as their peers is that they are more likely to face obstacles in their personal lives that may slow or delay their college progress. In their 2018 study, Strumbos et al. report that if a student does not complete twenty credits per year, they are not likely to complete their degree. Unfortunately, this “degree momentum” is often difficult for low-income students to achieve due to what Nathan Favero (2018), a professor of public policy at American University, calls “personal barriers to success.” For example, Favero (2018) notes that low-income students may be single parents who lack support from other family members, and so they “can feel a strong pull to pause their studies and start working” (para. 7) when unexpected bills arise. Diana Strumbos and her colleagues agree that “Work and family obligations sometimes force students to attend part time, which can again lead to a loss of momentum and decrease their likelihood of graduating” (Strumbos et al., 2018, p. 102). Therefore, typical degree programs and schedules often do not serve low-income students.

Transitional phrases: for example, therefore

Signal phrases: Report, notes, agree

Check Your Understanding: Using Transition and Signal Phrases

Take a fully developed body paragraph and edit it for the use of transition phrases and signal phrases to show context:

- Highlight all source material within the paragraph (quotes, paraphrases, and summaries)

- Review these highlighted passages to see:

- Have you addressed any of the five “w” questions for your sources? If not, is there anything more that your reader needs to understand about this source’s original context?

- Have you included signal verbs for your quotes and/or paraphrases? Do you have a variety of appropriate words (for example argues vs. believes vs. points out)?

- Have you used transitions to help show how sources’ ideas and your own ideas are related to each other?

Additional Resource: Roles of Sources Organizers

Download a copy of the Roles of Sources Graphic Organizer [PDF]

Roles of Sources Organizer (Text version)

| Area | What I know about this | Title of the source that provided this information | What I would still like to know about this |

|---|---|---|---|

| The past history of my topic | |||

| The wider context (including surrounding laws, cultures and circumstances) related to my topic | |||

| Definitions of key concepts related to my topic | |||

| Most important numbers, numerical data, or statistics related to my topic | |||

| Expert opinions or expert testimonies related to my topic | |||

| Counter-arguments (views that disagree with mine) related to my topic | |||

| specific stories about actual people (anecdotes) that are good examples of why my topic is important or relevant |

Activity source: “Roles of Sources Graphical Organizer” by Sarah Johnson and Jeremy O’Roark In Critical Reading, Critical Writing, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

Attribution & References

Except where otherwise noted, this section is adapted from “8 Integrating Sources” In Critical Reading, Critical Writing by Curated and/or composed by the English Faculty at Howard Community College, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

References

Banks-Santilli, L. (2015, June 2). Feet on campus, heart at home: First-generation college students struggle with divided identities. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/feet-on-campus-heart-at-home-first-generation-college-students-struggle-with-divided-identities-42158

Favero, N. (2018, May 8). Why graduation rates lag for low-income college students. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/why-graduation-rates-lag-for-low-income-college-students-96182

Nadworny, E. (2019, March 13). College completion rates are up, but the numbers will still surprise you. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2019/03/13/681621047/college-completion-rates-are-up-but-the-numbers-will-still-surprise-you

Page, L., & Keyhoe, S. S. (2016, May 26). Is a tuition-free policy enough to ensure college success? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/is-a-tuition-free-policy-enough-to-ensure-college-success-57947

Strumbmos, D., Linderman, D., & Hicks, C. C. (2018, February). Postsecondary Pathways out of poverty: City University of New York accelerated study in associate programs and the case for national policy.