8 Web strategy: Attracting and retaining visitors

Richard T. Watson (University of Georgia and USA)

Introduction

The Web changes the nature of communication between firms and customers. The traditional advertiser decides the message content, and on the Web, the customer selects the message. Traditional advertising primarily centers on the firm broadcasting a message. The flow of information is predominantly from the seller to the buyer. However, the Web puts this flow in reverse thrust. Customers have considerable control over which messages they receive because it is primarily by visiting Web sites that they are exposed to marketing communications. The customer intentionally seeks the message.[1]

The Web increases the richness of communication because it enables greater interactivity between the firm and its customers and among customers. The airline can e-mail frequent flyers special deals on underbooked flights. The prospective book buyer can search electronically by author, title, or genre. Customers can join discussion groups to exchange information on product bugs, innovative uses, gripes about service, and ask each other questions. Firms and customers can get much closer to each other because of the relative ease and low cost of electronic interaction.

Although there is some traditional advertising on the Web, especially that associated with search engines, in the main the communication relationship is distinctly different. This shift in communication patterns is so profound that major communication conglomerates are undergoing a strategic realignment. Increasingly, customers use search and directory facilities to seek information about a firm’s products and services. Consequently, persuading and motivating customers to seek out interactive marketing communication and interact with advertisers is the biggest challenge facing advertisers in the interactive age.

In the new world of Web advertising, the rules are different. The Web, compared to other media, provides a relatively level playing field for all participants in that:

- access opportunities are essentially equal for all players, regardless of size;

- share of voice is essentially uniform–no player can drown out others;

- initial set-up costs present minimal or nonexistent barriers to entry.

A small company with a well-designed home page can look every bit as professional and credible as a large, multinational company. People can’t tell if you do business from a 90-story office building or a two-room rented suite. Web home pages level the playing field for small companies.

Differentiation–success in appealing to desirable market segments so as to maintain visibility, create defensible market positions, and forge institutional identity–is considered to be a central key to survival and growth for businesses in the new electronic marketplace. In other words:

How do you create a mountain in a flat world?

An attractor is a Web site with the potential to attract and interact with a relatively large number of visitors in a target stakeholder group (for example, an auto company will want to attract and interact with more prospective buyers to its Web site than its competitors). While the Web site must be a good attractor, it must also have the facility for interaction if its powers of attraction are to have a long life span. Merely having attraction power is not enough–the site might attract visitors briefly or only once. The strength of the medium lies in its abilities to interact with buyers, on the first visit and thereafter. Good sites offer interaction above all else; less effective sites may often look more visually appealing, but offer little incentive to interact. Many organizations have simply used the Web as an electronic dumping ground for their corporate brochures–this in no way exploits the major attribute of the medium–its ability to interact with the visitor. Purely making the corporate Web site a mirror of the brochure is akin to a television program that merely presents visual material in the form of stills, with little or no sound. Television’s major attribute is its ability to provide motion pictures and sounds to a mass audience, and merely using it as a platform for showing still graphics and pictures does not exploit the medium. Thus, very little television content is of this kind today. Similarly, if Web sites are not interactive, they fail to exploit the potential of the new medium. The best Web sites both attract and interact–for example, the BMW site shows pictures of its cars and accompanies these with textual information. More importantly, BMW allows the visitor to see and listen to the new BMW Z3 coupe, redesign the car by seeing different color schemes and specifications, and drive the car using virtual reality. This is interaction with the medium rather than mere reaction to the medium.

We propose that the strategic use of hard-to-imitate attractors, building blocks for gaining visibility with targeted stakeholders, will be a key factor in on-line marketing. Creating an attractor will, we believe, become a key component of the strategy of some firms. This insight helps define the issues we want to focus on in this chapter:

Types of attractors

Given the recency of the Web, there is limited prior research on electronic commerce, and theories are just emerging. In new research domains, observation and classification are common features of initial endeavors. Thus, in line with the pattern coding approach of qualitative research, we sought overriding concepts to classify attractors.

To understand how firms distinguish themselves in a flat world, we reviewed marketing research literature, surfed many Web sites (including specific checks on innovations indicated in What’s New pages or sections), monitored Web sites that publish reviews of other companies’ Web efforts, and examined prize lists for innovative Web solutions.

After visiting many Web sites and identifying those that seem to have the potential to attract a large number of visitors, we used metaphors to label and group sites into categories (see Exhibit 1). The categories are not mutually exclusive, just as the underlying metaphors are not distinct categories. For example, we use both the archive and entertainment park as metaphors. In real life, archives have added elements of entertainment (e.g., games that demonstrate scientific principles) and entertainment parks recreate historical periods (e.g., Frontierland at Disney).

Exhibit 1.: Types of attractors

| The entertainment park |

| The archive |

| Exclusive sponsorship |

| The Town Hall |

| The club |

| The gift shop |

| The freeway intersection or portal |

| The customer service center |

The entertainment park

Web sites in this category engage visitors in activities that demand a high degree of participation while offering entertainment. Many use games to market products and enhance corporate image. These sites have the potential to generate experiential flow, because they provide various degrees of challenge to visitors. They are interactive and often involve elements and environments that promote telepresence experiences. The activities in the entertainment park often have the character of a contest, where awards can be distributed through the network (e.g., the Disney site). These attractors are interactive, recreational, and challenging. The potential competitive advantages gained through these attractors are high traffic potential (with repeat visits) and creation or enforcement of an image of a dynamic, exciting, and friendly corporation.

Examples in this category include:

- GTE Laboratories’ Fun Stuff part of its Web site, which includes Web versions of the popular games MineSweeper, Rubik’s cube, and a 3D maze for Web surfers to navigate;

- The Kellogg Company’s site lets young visitors pick a drawing and color it by selecting from a palette and clicking on segments of the picture;

- Visitors to Karakas VanSickle Ouellette Advertising and Public Relations can engage in the comical Where’s Pierre game and win a T-shirt by discovering the whereabouts of Pierre Ouellette, KVO’s creative big cheese ;

- Joe Boxer uses unusual effects and contests for gaining attention. For solving an advanced puzzle, winners gain supplies of virtual underwear. Instructions such as “Press the eyeball and you will return to the baby,” are a blend of insanity and advertising genius.

The archive

Archive sites provide their visitors with opportunities to discover the historical aspects of the company’s activities. Their appeal lies in the instant and universal access to interesting information and the visitor’s ability to explore the past, much like museums or maybe even more like the more recently created exploratoria (entertainment with educational elements). The credibility of a well-established image is usually the foundation of a successful archive, and building and reinforcing this corporate image is the main marketing role of the archive.

The strength of these attractors is that they are difficult to imitate, and often impossible to replicate. They draw on an already established highly credible feature of the company, and they bring an educational potential, thus reinforcing public relations aspects of serving the community with valuable information. The major weakness is that they often lack interactivity and are static and less likely to attract repeat visits. The potential competitive advantage gained through these attractors is the building and maintenance of the image of a trusted, reputable, and well-established corporation.

Examples in this category include:

- Ford’s historical library of rare photos and a comprehensive story of the Ford Motor Company;

- Boeing’s appeal to aircraft enthusiasts by giving visitors a chance to find out more about its aircraft through pictures, short articles on new features, and technical explanations;

- Hewlett-Packard’s site where everyone can check out the Palo Alto garage in which Bill Hewlett and Dave Packa rd started the firm.

Exclusive sponsorship

An organization may be the exclusive sponsor of an event of public interest, and use its Web site to extend its audience reach. Thus, we find on the Internet details of sponsored sporting competitions and broadcasts of special events such as concerts, speeches, and the opening of art exhibitions.

Sponsorship attractors have broad traffic potential and can attract many visitors in short periods (e.g., the World Cup). They can enhance the image of the corporation through the provision of timely, exclusive, and valuable information. However, the benefits of the Web site are lost unless the potential audience learns of its existence. This is a particular problem for short-term events when there is limited time to create customer awareness. Furthermore, the information on the Web site must be current. Failure to provide up-to-the-minute results for many sporting events could have an adverse effect on the perception of an organization.

Examples of sponsorship include:

- Texaco publishes the radio schedule for the Metropolitan Opera, which it sponsors on National Public Radio;

- Coca-Cola gives details of Coke-sponsored concerts and sporting events;

- Planet Reebok includes interviews with the athletes it sp onsors. The Web site permits visitors to post questions to coaches and players.

A Web site can provide a venue for advertisers excluded from other media. For instance, cigarette manufacturer Rothmans, the sponsor of the Cape Town to Rio de Janeiro yacht race, has a Web site devoted to this sporting event.

The town hall

The traditional town hall has long been a venue for assembly where people can hear a famous person speak, attend a conference, or participate in a seminar. The town hall has gone virtual, and these public forums are found on the Web. These attractors can have broad traffic potential when the figure is of national importance or is a renowned specialist in a particular domain. Town halls have a potentially higher level of interactivity and participation and can be more engaging than sponsorship. However, there is the continuing problem of advising the potential audience of who is appearing. There is a need for a parallel bulletin board to notify interested attendees about the details of town hall events. Another problem is to find a continual string of drawing card guests.

Examples in this category are:

- Tripod, a resource center for college studen ts, has daily interviews with people from a wide variety of areas. Past interviews are archived under categories of Living, Travel, Work, Health, Community, and Money.

- CMP Publications Inc., a publisher of IT magazines (e.g., InformationWeek ), hosts a Cyberforum, where an IT guru posts statements on a topic (e.g., Windows 2000) and responds to issues raised by readers.

The club

People have a need to be part of a group and have satisfactory relationships with others. For some people, a Web club can satisfy this need. These are places to hang out with your friends or those with similar interests. On the Internet, the club is an electronic community, which has been a central feature of the Internet since its foundation. Typically, visitors have to register or become members to participate, and they often adopt electronic personas when they enter the club. Web clubs engage people because they are interactive and recreational. Potentially, these attractors can increase company loyalty, enhance customer feedback, and improve customer service through members helping members .

Examples include:

- Snapple Beverage Company gives visitors the opportunity to meet each other with personal ads (free) that match people using attributes such as favorite Snapple flavor;

- Zima’s loyalty club, Tribe Z, where members can access exclusive areas of the site;

- Apple’s EvangeList, a bulletin board for maintaining the faith of Macintosh devotees.

An interesting extension of this attractor is the electronic trade show, with attached on-line chat facilities in the form of a MUD (multiuser dungeon) or MOO (multiuser dungeon object oriented). Here visitors can take on roles and exchange opinions about products offered at the show.

The gift shop

Gifts and free samples nearly always get attention. Web gifts typically include digitized material such as software (e.g., screensavers and utilities), photographs, digital paintings, research reports, and non-digital offerings (e.g., a T-shirt). Often, gifts are provided as an explicit bargain for dialogue participation (e.g., the collection of demographic data).

- Ameritech’s Claude Monet exhibition where yo u can download digital paintings;

- Kodak’s library of colorful, high-quality digital images that are downloadable;

- Ragu Foods offers recipes, Italian-language lessons, merchandise, and stories written by Internet users. You can e-mail a request for product coupons. There is culture, too, in the form of an architectural tour of a typical Pompeiian house;

- MCA/Universal Cyberwalk offers audio and video clips from upcoming Universal Pictures’ releases, and a virtual tour of Uni versal Studios, Hollywood’s new ride based on Back to the Future. There is even a downloadable coupon hidden in the area that will let you bypass the line for the ride at the theme park.

One noteworthy subspecies of the gift is the software utility or update. Many software companies distribute upgrades and complimentary freeware or shareware via their Web site. In some situations (e.g., a free operating system upgrade), this can generate overwhelming traffic for one or two weeks. Because some software vendors automatically notify registered customers by e-mail whenever they add an update or utility, such sites can have bursts of excessively high attractiveness.

The freeway intersections or portals

Web sites that provide advanced information processing services (e.g., search engines) can become n-dimensional Web freeway intersections with surfers coming and going in all directions, and present significant advertising opportunities because the traffic flow is intense–rather like traditional billboard advertising in Times Square or Picadilly Circus. Search engines, directories, news centers, and electronic malls can attract hundreds of thousands of visitors in a day.

Some of these sites are entry points to the Web for many people, and are known as portals. These portals are massive on-ramps to the Internet. A highly successful portal, such as America Online, attracts a lot of traffic.

Within this category, we also find sites that focus upon specific customer segments and try to become their entry points to the Web. Demography (e.g., an interest in fishing) and geography (such as Finland Online’s provision of an extensive directory for Finland) are possible approaches to segmentation. The goal is to create a one-stop resource center. First movers who do the job well are likely to gain a long-term competitive advantage because they have secured prime real estate, or what conventional retailers might call a virtual location.

- Yahoo!, a hierarchical directo ry of Web sites;

- ISWorld, an entry point to serve the needs of information systems academics and students;

- AltaVista, a Web search engine originally operated by Digital (since acquired by Compaq Computers) as a means of promoting its Alpha servers.

The customer service center

By directly meeting their information needs, a Web site can be highly attractive to existing customers. Many organizations now use their Web site to support the ownership phase of the customer service life cycle. For instance, Sprint permits customers to check account balances, UPS has a parcel tracking service, many software companies support downloading of software updates and utilities (e.g., Adobe), and many provide answers to FAQs or frequently asked questions (e.g., Fuji Film). The Web site is a customer service center. When providing service to existing customers, the organization also has the opportunity to sell other products and services. A visitor to the Apple Web site, for example, may see the special of the week displayed prominently.

Summary

Organizations are taking a variety of approaches to making their Web sites attractive to a range of stakeholders. Web sites can attract a broad audience, some of whom are never likely to purchase the company’s wares, but could influence perceptions of the company, and certainly increase word-of-mouth communication, which could filter through to significant real customers. Other Web sites focus on serving one particular stakeholder–the customer. They can aim to increase market share by stimulating traffic to their site (e.g., Kellogg’s) or to increase the share of the customer by providing superior service (e.g., the UPS parcel tracking service).

Of course, an organization is not restricted to using one form of attractor. It makes good sense to take a variety of approaches so as to maximize the attractiveness of a site and to meet the diverse needs of Web surfers. For example, Tripod uses a variety of attractors to draw traffic to its site. By making the site a drawing card for college students, Tripod can charge advertisers higher rates. As Exhibit 2 illustrates, there are some gaps. Tripod is not an archive or the exclusive sponsor of an event.

Exhibit 2.: Tripod’s use of attractors

Attractiveness factors

The previous examples illustrate the variety of tactics used by organizations to make their sites attractors. There is, however, no way of ensuring that we have identified a unique set of categories. There may be other types of attractors that we simply did not recognize or uncover in our search. To gain a deeper understanding of attractiveness, we examine possible dimensions for describing the relationship between a visitor and a Web site. The service design literature, and in particular the service process matrix, provide the stimulus for defining the elements of attractiveness.

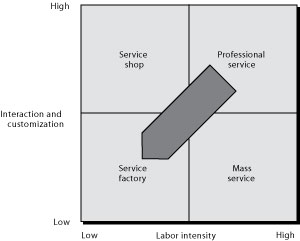

The service process matrix (see Exhibit 3), with dimensions of degree of labor intensity and interaction and customization, identifies four types of service businesses. Labor-intensive businesses have a high ratio of cost of labor relative to the value of plant and equipment (e.g., law firms). A trucking firm, with a high investment in trucks, trailers, and terminals, has low labor intensity. Interaction and customization are, respectively, the extent to which the consumer interacts with the service process and the service is customized for the consumer.

|

Exhibit 3.: The service process matrix (Adapted from Schmener) |

Because services are frequently simultaneously produced and consumed, they are generally easier to customize than products. A soft drink manufacturer would find it almost impossible to mix a drink for each individual customer, while dentists tend to customize most of the time, by treating each patient as an individual. The question facing most firms, of course, is to what extent they wish to customize offerings.

For many services, customization and interaction are associated. High customization often means high interaction (e.g., an advertising agency) and low customization is frequently found with low interaction (e.g., fast food), though this is not always the case (e.g., business travel agents have considerable interaction with their customers but little customization because airline schedules are set). The push for lower costs and control is tending to drive services towards the diagonal. The traditional carrier, for example, becomes a no-frills airline by moving towards the lower-left.

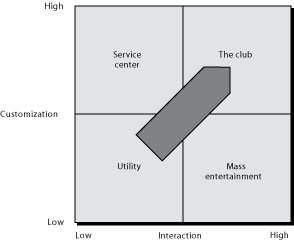

If we now turn to the Web, labor intensity disappears as a key element because the Web is an automated service delivery system. Hence, we focus our attention on interaction and customization and split these out as two separate elements to create the attractors grid (see See Attractors grid). Attractors require varying degrees of visitor interaction. A search engine simply requires the visitor to enter search terms. While the customers may make many searches, on any one visit there is little interaction. Just like a real entertainment park, a Web park is entertaining only if the visitor is willing to participate (e.g., play an interactive game). The degree of customization varies across attractors from low (e.g., the digital archive) to high (e.g., a customer service center).

Each of the four quadrants in the attractors grid has a label. A utility (e.g., search engine) requires little interaction and there is no customization, each customer receives the same output for identical keywords. A service center provides information tailored to the customer’s current concern (e.g., what is the balance of my account?). In mass entertainment (e.g., an entertainment park), the visitor participates in an enjoyable interaction, but there is no attempt to customize according to the needs or characteristics of the visitor. The atmosphere of a club is customized interaction. The club member feels at home because of the personalized nature of the interaction.

Exhibit 4.: Attractors grid

In contrast to the service process matrix’s push down the diagonal, the impetus with attractors should be towards customized service–up the diagonal (see Exhibit 4). The search engine, which falls in the utility quadrant, needs to discover more about its visitors so that it can become a customer service center. Similarly, mass entertainment should be converted to the personalized performance and interaction of a club. The service center can also consider becoming a club so that frequent visitors receive a special welcome and additional service, like hotel guests who are recognized by the concierge. Indeed, commercial Internet success may be dependent on creating clubs or electronic communities.

Where possible, organizations should be using the Web to reverse the trend away from customized service by creating highly customized attractors. Simultaneously, we could see the synergistic effects of both trends. A Web application reduces labor intensity and increases customization. This can come about because the model in See The service process matrix (Adapted from Schmenner) assumes that people deliver services, but when services are delivered electronically, the dynamics change. In this respect, the introduction of the Web is a discontinuity for some service organizations, and represents an opportunity for some firms to change the structure of the industry.

A potential of the Web is that it will make mass customization work. It will enable customized service to each customer, while serving millions of them at the same time. All customers will get more or less what they want, tailored to what is unique to them and their circumstances. This will be achieved, almost without exception, by information technology. The really important aspect of this is that by mass customization, the firm will learn from customers; more importantly, customers are more likely to remain loyal, not so much because the firm serves them so well, but because they do not want to teach another firm what’s already known about them by their current provider.

Sustainable attractiveness

The problem with many Web sites, like many good ideas, is that they are easily imitated. In fact, because the Web is so public, firms can systematically analyze each other’s Web sites. They can continually monitor the Web presence of competitors and, where possible, quickly imitate many initiatives. Consequently, organizations need to be concerned with sustainable attractiveness–the ability to create and maintain a site that continues to attract targeted stakeholders. In the case of a Web site, sustainable attractiveness is closely linked to the ease with which a site can be imitated.

Attractors can be classified by ease of imitation, an assessment of the cost and time to copy another Web site’s concept (see See Ease of imitation of attractors). The easiest thing to reproduce is information that is already in print (e.g., the corporate brochure). Product descriptions, annual reports, price lists, product photographs, and so forth can be converted quickly to HTML, GIFs, or an electronic publishing format such as Adobe’s portable document format (PDF). Indeed, this sort of information is extremely common on the Web, and so bland that we consider it has minimal attractiveness.

Exhibit 5.: Ease of imitation of attractors

| Ease of imitation | Examples of attractors |

| Easy | Corporate brochure |

| Imitate with some effort | Software utilitiesDirectory or search engine |

| Costly to imitate | Advanced customer service application SponsorshipValuable and rare resources |

| Impossible to imitate | Archive with some exclusive features Well-established brand name or corporate image |

There is a variety of attractors, such as utilities, that can be imitated with some effort and time. The availability of multiple search engines and directories clearly supports this contention. The original offerer may gain from being a first mover, but distinctiveness will be hard to sustain. Nevertheless, while investing in easily imitated attractors may provide little gain, firms may have to match their competitors’ offerings so as to remain equally attractive, thus echoing the notion of strategic necessity of the strategic information systems literature. Attractors are more like services than products. Innovations generally are more easily imitated, just as the first life insurance company to offer premium discounts to nonsmokers was easily imitated (and therefore not remembered).

While a search engine or directory can be imitated, what is less difficult to copy is location or identity. Some search engines are better placed than others. For example, clicking on Netscape’s Search button gives immediate access to Netscape’s search engine, and additional clicks are required to access competitive search engines. This is like being the first gas station after the freeway exit or the only one on a section of highway with long distances between exit ramps. It is one of the best pieces of real estate on the information superhighway, and certainly Netscape should gain a high rent for this spot.

The key to imitation is whether a firm possesses valuable and rare resources and how much it costs to duplicate these resources or how readily substitutes can be found. Back-end computer applications that support Web front-end customer service can be a valuable resource, though not rare. FedEx’s parcel tracking service is an excellent example of a large investment back-end IT application easily imitated by competitor UPS. IT investment can create a competitive advantage, but it is unlikely to be sustainable because competitors can eventually duplicate the system.

Sponsorship is another investment that can create a difficult-to-imitate attractor. Signing a long-term contract to sponsor a major sporting or cultural event can create the circumstances for a long-lived attractor. Sponsorship is a rare resource, but its very rareness may induce competitors to escalate the cost of maintaining sponsorship for popular events. Contracts eventually run their course, and failure to win the next round of the bidding war will mean loss of the attractor.

There are some attractors that can never be imitated or for which there are few substitutes. No other beverage company can have a Coke Museum–real or virtual. Firms with respected and well-known brands (e.g., Coca-Cola) have a degree of exclusiveness that they can impart to their Web sites. The organization that owns a famous Monet painting can retain exclusive rights to offer the painting as a screensaver. For many people, there is no substitute for the Monet painting. These attractors derive their rareness from the reputation and history of the firm or the object. History can be a source of enduring competitiveness and, in this case, enduring attractiveness.

This analysis suggests that Web application designers should try to take advantage of:

- prior back-end IT investments that take time to duplicate;

- special relations (e.g., sponsorship);

- special information resources (e.g., an archive);

- established brand or image (part of the enterprise’s history);

- proprietary intellectual/artistic capital (e.g., a Monet painting).

Strategies for attractors

Stakeholder analysis can be a useful tool for determining which types and forms of attractors to develop. Adapting the notion that a firm should sell to the most favorable buyers, an organization should concentrate on using its Web site to attract the most influential stakeholders. For example, it might use an attractor to communicate with employees or it may want to attract and inform investors and potential suppliers.

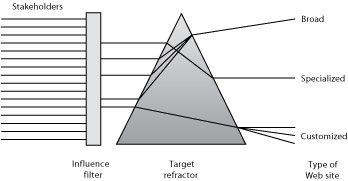

After selecting the targeted stakeholder group, the organization needs to decide the degree of focus of its attraction. We proffer a two-stage process for selecting the properties of an attractor (see Exhibit 6). First, identify the target stakeholder groups and make the site more attractive to these groups–the influence filter. Second, decide the degree of customization–the target refractor. For example, Kellogg’s Web site, designed to appeal to all young children, filters but is not customized. American Airlines’ Web site is an implementation of filtering and customization. The site is designed to attract prospective flyers (filtering). Frequent flyers, an important stakeholder group, have access to their mileage numbers by entering their frequent flyer number and a personal code (customization).

|

|

Broad attraction

A broad attractor can be useful for communicating with a number of types of stakeholders or many of the people in one category of stakeholders. Many archives, entertainment parks, and search engines have a general appeal, and there is no attempt to attract a particular segment of a stakeholder group. For example, Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company’s Web site, with its information on tires, is directed at the general tire customer. A broad attractor provides content with minimal adjustment to the needs of the visitor. Thus, many visitors may not linger too long at the site because there is nothing that particularly catches their attention or meets a need. In terms of See Attractors grid, broad attractors are utilities or mass entertainment.

Specialized attraction

A specialized attractor appeals to a more narrow audience. UPS, with its parcel tracking system, has decided to focus on current customers. A customer can enter an tracking number to determine the current location of a package and download software for preparing transportation documentation. A specialized attractor can be situation dependent. It may attract fewer visitors, but nearly all those who make the link find the visit worthwhile. A specialized attractor may be a utility (providing solutions to a particular class of problem) or a service center (providing service to a specific group of stakeholders) (see See Attractors grid).

Personalized attractor

The marketer’s goal is to develop an interactive relationship with individual customers. Personalized attractors, an incarnation of that dream, can be customized to meet the needs of the individual visitor. Computer magazine publisher Ziff-Davis offers visitors the opportunity to specify a personal profile. After completing a registration form, the visitor can then select what to see on future visits. For instance, a marketing manager tracking the CAD/CAM software market in Germany can set a profile that displays links to new stories on these topics. On future visits to the Ziff-Davis site, the manager can click on the personal view button to access the latest news matching the profile. The Mayo Clinic uses the Internet Chat facility to host a series of monthly on-line forums with Clinic specialists. The forums are free, and visitors may directly question an endocrinologist, for instance. Thus, visitors can get advice on their particular ailments.

There are two types of personalized attractors. Adaptable attractors can be customized by the visitor, as in the case of Ziff-Davis. The visitor establishes what is of interest by answering questions or selecting options. Adaptive attractors learn from the visitor’s behavior and determine what should be presented. Advanced Web applications will increasingly use a visitor’s previously gathered demographic data and record of pages browsed to create dynamically a personalized set of Web pages, just as magazines can be personalized.

One advantage of a personalized attractor is that it can create switching costs, which are not necessarily monetary, for the visitor. Although establishing a personal profile for an adaptable site is not a relatively high cost for the visitor, it can create some impediment to switching. An adaptive Web site further raises costs because the switching visitor will possibly have to suffer an inferior service while the new site learns what is relevant to the customer. Furthermore, an organization that offers an adaptable or adaptive Web site as a means of differentiation learns more about each customer. Since the capacity to differentiate is dependent on knowing the customer, the organization is better placed to further differentiate itself. Personalized attractors can provide a double payback–higher switching cost for customers and greater knowledge of each customer.

The flexibility of information technology means that organizations can build a Web page delivery platform that will produce a variety of customized pages. Thus, it is quite feasible for the visitor to determine before each access whether to receive a standard or customized page. For example, visitors could decide to receive the standard version of an electronic newspaper or one that they tailored. This choice might go hand in hand with a differential pricing mechanism so that visitors pay for customization, just as they do with many physical products. Flexible Web server systems should make it possible for organizations to provide simultaneously both broad and customized attractors. The choice then is not between types of attractors, but how much should the visitor pay for degrees of customization.

Conclusion

Because we often learn by modeling the behavior of others, we have used metaphors and examples to illustrate the variety of attractors that are currently operational. These should provide a useful starting point for practitioners designing attractors because a variety of stimuli are the most important means of stimulating creative behavior. However, we have no way of verifying that we have covered the range of metaphors, and other useful ones may emerge as organizations discover innovative uses of the Web. The attractors grid (see See Attractors grid) is a more formal method of classifying attractors, and provided we have identified the key parameters for describing attractors, does indicate complete coverage of the types of attractors.

The difference in the direction of the diagonal in the service process matrix and attractors grid suggests a discontinuity in the approach to delivering service. For some services, there should no longer be a reduction but an increase in customization as human-delivered services are replaced by Web service systems. Thus, this chapter provides two decision aids, metaphors and the attractor grid, for those attempting to identify potential attractors, and these challenge managers to rethink the current trend in service delivery.

The attractor strategy model is the third decision aid proffered. Its purpose is to stimulate thinking about the audience to be attracted and the degree of interactivity with it. The attractor strategy model is promoted as a tool for linking attractors to a stakeholder-driven view of strategy. In our view, attractors are strategic information systems and must be aligned with organizational goals.

Web sites have the potential for creating competitive advantage by attracting numerous visitors so that many potential customers learn about a firm’s products and services or influential stakeholders gain a positive impression of the firm. The advantage, however, may be short-lived unless the organization has some valuable and rare resource (e.g., sponsorship of a popular sporting event) that cannot be duplicated. A valuable, but not necessarily rare, resource for many organizations is the current IT infrastructure. Firms should find it useful to re-examine their existing databases to gauge their potential for highly attractive Web applications. Building front-end Web applications to create an attractor (e.g., customer service) can be a quick way of capitalizing on existing investments, but competitors are likely to be undertaking the same projects. IT infrastructure, however, is not enough to create a sustained attractor. The key assets are managerial IT skills and viewing information as the key asset that can create competitive advantage. Sustainable attractiveness is dependent on managers understanding what information to deliver and how to present it to stakeholders.

References

Armstrong, A., and J. Hagel. 1996. The real value of on-line communities. Harvard Business Review 74 (3):134-141.

Peppers, D., and M. Rogers. 1993. The one to one future: building relationships one customer at a time . New York, NY: Currency Doubleday.

Pine, B. J., B. Victor, and A. C. Boynton. 1993. Making mass customization work. Harvard Business Review 71 (5):108-119.

Schmenner, R. W. 1986. How can a service business prosper? Sloan Management Review 27 (3):21-32.

- This chapter is based on Watson, R. T., S. Akselsen, and L. F. Pitt. 1998. Attractors: building mountains in the flat landscape of the World Wide Web. California Management Review 40 (2):36-56. ↵