1 An Introduction

Richard T. Watson (University of Georgia and USA)

Electronic commerce is a revolution in business practices. If organizations are going to take advantage of new Internet technologies, then they must take a strategic perspective. That is, care must be taken to make a close link between corporate strategy and electronic commerce strategy.

In this chapter, we address some essential strategic issues, describe the major themes tackled by this book, and outline the other chapters. Among the central issues we discuss are defining electronic commerce, identifying the extent of a firm’s Internet usage, explaining how electronic commerce can address the three strategic challenges facing all firms, and understanding the parameters of disintermediation. Consequently, we start with these issues.

Electronic commerce defined

Electronic commerce, in a broad sense, is the use of computer networks to improve organizational performance. Increasing profitability, gaining market share, improving customer service, and delivering products faster are some of the organizational performance gains possible with electronic commerce. Electronic commerce is more than ordering goods from an on-line catalog. It involves all aspects of an organization’s electronic interactions with its stakeholders, the people who determine the future of the organization. Thus, electronic commerce includes activities such as establishing a Web page to support investor relations or communicating electronically with college students who are potential employees. In brief, electronic commerce involves the use of information technology to enhance communications and transactions with all of an organization’s stakeholders. Such stakeholders include customers, suppliers, government regulators, financial institutions, mangers, employees, and the public at large.

Who should use the Internet?

Every organization needs to consider whether it should have an Internet presence and, if so, what should be the extent of its involvement. There are two key factors to be considered in answering these questions.

First, how many existing or potential customers are likely to be Internet users? If a significant proportion of a firm’s customers are Internet users, and the search costs for the product or service are reasonably (even moderately) high, then an organization should have a presence; otherwise, it is missing an opportunity to inform and interact with its customers. The Web is a friendly and extremely convenient source of information for many customers. If a firm does not have a Web site, then there is the risk that potential customers, who are Web savvy, will flow to competitors who have a Web presence.

Second, what is the information intensity of a company’s products and services? An information-intense product is one that requires considerable information to describe it completely. For example, what is the best way to describe a CD to a potential customer? Ideally, text would be used for the album notes listing the tunes, artists, and playing time; graphics would be used to display the CD cover; sound would provide a sample of the music; and a video clip would show the artist performing. Thus, a CD is information intensive; multimedia are useful for describing it. Consequently, Sony Music provides an image of a CD’s cover, the liner notes, a list of tracks, and 30-second samples of some tracks. It also provides photos and details of the studio session.

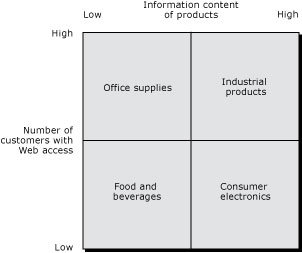

The two parameters, number of customers on the Web and product information intensity, can be combined to provide a straightforward model (see Exhibit 1) for determining which companies should be using the Internet. Organizations falling in the top right quadrant are prime candidates because many of their customers have Internet access and their products have a high information content. Firms in the other quadrants, particularly the low-low quadrant, have less need to invest in a Web site.

Exhibit 1.: Internet presence grid

Why use the Internet?

Along with other environmental challenges, organizations face three critical strategic challenges: demand risk, innovation risk, and inefficiency risk. The Internet, and especially the Web, can be a device for reducing these risks.

Demand risk

Sharply changing demand or the collapse of markets poses a significant risk for many firms. Smith-Corona, one of the last U.S. manufacturers of typewriters, filed for bankruptcy in 1995. Cheap personal computers destroyed the typewriter market. In simple terms, demand risk means fewer customers want to buy a firm’s wares. The globalization of the world market and increasing deregulation expose firms to greater levels of competition and magnify the threat of demand risk. To counter demand risk, organizations need to be flexible, adaptive, and continually searching for new markets and stimulating demand for their products and services.

The growth strategy matrix [Ansoff, 1957] suggests that a business can grow by considering products and markets, and it is worthwhile to speculate on how these strategies might be achieved or assisted by the Web. In the cases of best practice, the differentiating feature will be that the Web is used to attain strategies that would otherwise not have been possible. Thus, the Web can be used as a market penetration mechanism, where neither the product nor the target market is changed. The Web merely provides a tool for increasing sales by taking market share from competitors, or by increasing the size of the market through occasions for usage. The U.K. supermarket group Tesco is using its Web site to market chocolates, wines, and flowers. Most British shoppers know Tesco, and many shop there. The group has sold wine, chocolates and flowers for many years. Tesco now makes it easy for many of its existing customers (mostly office workers and professionals) to view the products in a full-color electronic catalogue, fill out a simple order form with credit card details, write a greeting card, and facilitate delivery. By following these tactics, Tesco is not only taking business away from other supermarkets and specialty merchants, it is also increasing its margins on existing products through a premium pricing strategy and markups on delivery.

Alternatively, the Web can be used to develop markets , by facilitating the introduction and distribution of existing products into new markets. A presence on the Web means being international by definition, so for many firms with limited resources, the Web will offer hitherto undreamed-of opportunities to tap into global markets. Icelandic fishing companies can sell smoked salmon to the world. A South African wine producer is able to reach and communicate with wine enthusiasts wherever they may be, in a more cost effective way. To a large extent, this is feasible because the Web enables international marketers to overcome the previously debilitating effects of time and distance, negotiation of local representation, and the considerable costs of promotional material production costs.

A finer-grained approach to market development is to create a one-to-one customized interaction between the vendor and buyer. Bank America offers customers the opportunity to construct their own bank by pulling together the elements of the desired banking service. Thus, customers adapt the Web site to their needs. Even more advanced is an approach where the Web site is adaptive. Using demographic data and the history of previous interactions, the Web site creates a tailored experience for the visitor. Firefly markets technology for adaptive Web site learning. Its software tries to discover, for example, what type of music a visitor likes so that it can recommend CDs. Firefly is an example of software that, besides recommending products, electronically matches a visitor’s profile to create virtual communities, or at least groups of like-minded people–virtual friends–who have similar interests and tastes.

Any firm establishing a Web presence, no matter how small or localized, instantly enters global marketing. The firm’s message can be watched and heard by anyone with Web access. Small firms can market to the entire Internet world with a few pages on the Web. The economies of scale and scope enjoyed by large organizations are considerably diminished. Small producers do not have to negotiate the business practices of foreign climes in order to expose their products to new markets. They can safely venture forth electronically from their home base. Fortunately, the infrastructure–international credit cards (e.g., Visa) and international delivery systems (e.g., UPS)–for global marketing already exists. With communication via the Internet, global market development becomes a reality for many firms, irrespective of their size or location.

The Web can also be a mechanism that facilitates product development , as companies who know their existing customers well create exciting, new, or alternative offerings for them. The Sporting Life is a U.K. newspaper specializing in providing up-to-the-minute information to the gaming fraternity. It offers reports on everything from horse and greyhound racing to betting odds for sports ranging from American football to snooker, and from golf to soccer. Previously, the paper had been restricted to a hard copy edition, but the Web has given it significant opportunities to increase its timeliness in a time sensitive business. Its market remains, to a large extent, unchanged–bettors and sports enthusiasts in the U.K. However, the new medium enables it to do things that were previously not possible, such as hourly updates on betting changes in major horse races and downloadable racing data for further spreadsheet and statistical analysis by serious gamblers. Most importantly, The Sporting Life is not giving away this service free, as have so many other publishers. It allows prospective subscribers to sample for a limited time, before making a charge for the on-line service.

Finally, the Web can be used to diversify a business by taking new products to new markets. American Express Direct is using a Web site to go beyond its traditional traveler’s check, credit card, and travel service business by providing on-line facilities to purchase mutual funds, annuities, and equities. In this case, the diversification is not particularly far from the core business, but it is feasible that many firms will set up entirely new businesses in entirely new markets.

Innovation risk

In most mature industries, there is an oversupply of products and services, and customers have a choice, which makes them more sophisticated and finicky consumers. If firms are to continue to serve these sophisticated customers, they must give them something new and different; they must innovate. Innovation inevitably leads to imitation, and this imitation leads to more oversupply. This cycle is inexorable, so a firm might be tempted to get off this cycle. However, choosing not to adapt and not to innovate will lead to stagnation and demise. Failure to be as innovative as competitors–innovation risk–is a second strategic challenge. In an era of accelerating technological development, the firm that fails to improve continually its products and services is likely to lose market share to competitors and maybe even disappear (e.g., the typewriter company). To remain alert to potential innovations, among other things, firms need an open flow of concepts and ideas. Customers are one viable source of innovative ideas, and firms need to find efficient and effective means of continual communication with customers.

Internet tools can be used to create open communication links with a wide range of customers. E-mail can facilitate frequent communication with the most innovative customers. A bulletin board can be created to enable any customer to request product changes or new features. The advantage of a bulletin board is that another customer reading an idea may contribute to its development and elaboration. Also, a firm can monitor relevant discussion groups to discern what customers are saying about its products or services and those of its competitors.

Inefficiency risk

Failure to match competitors’ unit costs–inefficiency risk–is a third strategic challenge. A major potential use of the Internet is to lower costs by distributing as much information as possible electronically. For example, American Airlines now uses its Web site for providing frequent flyers an update of their current air miles. Eventually, it may be unnecessary to send expensive paper mail to frequent flyers or to answer telephone inquiries.

The cost of handling orders can also be reduced by using interactive forms to capture customer data and order details. Savings result from customers directly entering all data. Also, because orders can be handled asynchronously, the firm can balance its work force because it no longer has to staff for peak ordering periods.

Many Web sites make use of FAQs–frequently asked questions–to lower the cost of communicating with customers. A firm can post the most frequently asked questions, and its answers to these, as a way of expeditiously and efficiently handling common information requests that might normally require access to a service representative. UPS, for example, has answers to more than 40 frequent customer questions (e.g., What do I do if my shipment was damaged?) on its FAQ page. Even the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list is on the Web, and the FAQs detail its history, origins, functions, and potential.

Disintermediation

Electronic commerce offers many opportunities to reformulate traditional modes of business. Disintermediation , the elimination of intermediaries such as brokers and dealers, is one possible outcome in some industries. Some speculate that electronic commerce will result in widespread disintermediation, which makes it a strategic issue that most firms should carefully address. A closer analysis enables us to provide some guidance on identifying those industries least, and most, threatened by disintermediation.

Electronic commerce offers many opportunities to reformulate traditional modes of business. Disintermediation , the elimination of intermediaries such as brokers and dealers, is one possible outcome in some industries. Some speculate that electronic commerce will result in widespread disintermediation, which makes it a strategic issue that most firms should carefully address. A closer analysis enables us to provide some guidance on identifying those industries least, and most, threatened by disintermediation.

Consider the case of Manheim Auctions. It auctions cars for auto makers (at the termination of a lease) and rental companies (when they wish to retire a car). As an intermediary, it is part of a chain that starts with the car owner (lessor or rental company) and ends with the consumer. In a truncated value chain, Manheim and the car dealer are deleted. The car’s owner sells directly to the consumer. Given the Internet’s capability of linking these parties, it is not surprising that moves are already afoot to remove the auctioneer.

Edmunds, publisher of hard-copy and Web-based guides to new and used cars, is linking with a large auto-leasing company to offer direct buying to customers. Cars returned at the end of the lease will be sold with a warranty, and financing will be arranged through the Web site. No dealers will be involved. The next stage is for car manufacturers to sell directly to consumers, a willingness Toyota has expressed and that large U.S. auto makers are considering. On the other hand, a number of dealers are seeking to link themselves to customers through the Internet via the Autobytel Web site. Consumers contacting this site provide information on the vehicle desired and are directed to a dealer in their area who is willing to offer them a very low markup on the desired vehicle.

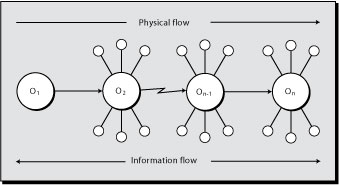

We gain greater insight into disintermediation by taking a more abstract view of the situation (see Exhibit 2). A value chain consists of a series of organizations that progressively convert some raw material into a product in the hands of a consumer. The beginning of the chain is 0 1 (e.g., an iron ore miner) and the end is O n (e.g., a car owner). Associated with a value chain are physical and information flows, and the information flow is usually bi-directional. Observe that it is really a value network rather than a chain, because any organization may receive inputs from multiple upstream objects.

Exhibit 2.: Value network

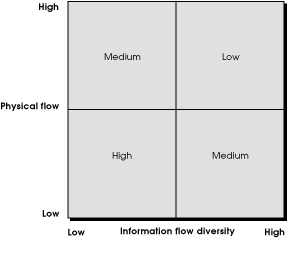

Consider an organization that has a relatively high number of physical inputs and outputs. It is likely this object will develop specialized assets for processing the physical flows (e.g., Manheim has invested heavily in reconditioning centers and is the largest non-factory painter of automobiles in the world). The need to process high volume physical flows is likely to result in economies of scale. On the information flow side, it is not so much the volume of transactions that matters since it is relatively easy to scale up an automated transaction processing system. It is the diversity of the information flow that is critical because diversity increases decision complexity. The organization has to develop knowledge to handle variation and interaction between communication elements in a diverse information flow (e.g., Manheim has to know how to handle the transfer of titles between states).

Combining these notions of physical flow size and information flow diversity, we arrive at the disintermediation threat grid (see ). The threat to Manheim is low because of its economies of scale, large investment in specialized assets that a competitor must duplicate, and a well-developed skill in processing a variety of transactions. Car dealers are another matter because they are typically small, have few specialized assets, and little transaction diversity. For dealers, disintermediation is a high threat. The on-line lot can easily replace the physical lot.

Exhibit 3: Disintermediation threat grid

We need to keep in mind that disintermediation is not a binary event (i.e., it is not on or off for the entire system). Rather, it is on or off for some linkages in the value network. For example, some consumers are likely to prefer to interact with dealers. What is more likely to emerge is greater consumer choice in terms of products and buying relationships. Thus, to be part of a consumer’s options, Manheim needs to be willing to deal directly with consumers. While this is likely to lead to channel conflict and confusion, it is an inevitable outcome of the consumer’s demand for greater choice.

Key themes addressed

First, we introduce a number of new themes, models, metaphors, and examples to describe the business changes that are implied by the Internet. An example of one of our metaphors is Joseph Schumpeter’s notion of creative destruction . That is, capitalist economies create new industries and new business opportunities. At the same time, these economies are destructive in that they sweep away old technologies and old ways of doing things. It is a sobering message that none of the major wagon makers was able to make the transition to automobile production. None of the manufacturers of steam locomotives became successful manufacturers of diesel locomotives. Will this pattern continue for the electronic revolution?

Amazon.com has relatively few employees and no retail outlets; and yet, it has a higher market capitalization than Barnes & Noble, which has more than one thousand retail outlets. Nonetheless, Barnes & Noble is fighting back by creating its own Web-based business. In this way, the Internet may spawn hybrid business strategies–those that combine innovative electronic strategies with traditional methods of competition. Traditional firms may survive in the twenty-first century, but they must adopt new strategies to compete. In this book, we introduce a variety of models for describing these new strategies, and we describe new ways for firms to compete by taking advantage of the opportunities that electronic commerce reveals.

Exhibit 4. Key themes addressed by this book

|

At the same time that information technology has the potential to transform business operations, it also has the potential to transform human behaviors and activities. The focus of our book is business strategy; so we concentrate on those human activities (e.g., consumer behavior) that intersect with business operations. Some examples of consumer behaviors that we discuss include: virtual communities; enhanced information search via the Web; e-mail exchanges (e.g., word-of-mouth communications about products, e-mail messages sent directly to organizations); direct consumer purchases over the Web (e.g., buying flowers, compact disks, software). Of course, the Internet creates new opportunities for organizations to gather information directly from consumers (e.g., interactively). The Internet provides a place where consumers can congregate and affiliate with one another. One implication is that organizations can make use of these new consumer groups to solve problems and provide consumer services in innovative ways. For instance, software or hardware designers can create chat rooms where users pose problems. At the same time, other consumers will visit the chat room and propose suggested solutions to these problems.

Value to organizations is one of our themes. As described previously, organizations can create value via the Internet by improving customer service. The stock market value of some high technology firms is almost unbelievable. Consider the U.S. steel industry, which dominated the American economy in the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. As of March 1999, the combined market capitalization of the 13 largest American steel firms (e.g., U.S. Steel and Bethlehem Steel) is approximately USD 6 billion , less than one-third the value of the Internet bookseller, Amazon.com. On most days, the market capitalization of Microsoft rises or falls by more than the market capitalization of the entire U.S. integrated steel industry. Firms such as Microsoft do not have extensive tangible assets, as the steel companies do. In contrast, Microsoft is a knowledge organization, and it is this knowledge (and ability to invent new technologies and new technological applications) that creates such tremendous value for shareholders.

At the same time, technology creates value for consumers. Some of this value comes in the form of enhanced products and services. Some of the value comes from more favorable prices (perhaps encouraged by the increased competition that the Internet can bring to selected industries). Some of the value comes in the form of enhanced (and more rapid) communications–communications between consumers and communications between organizations and consumers. In brief, the Internet raises quality of life, and it has the potential to perform this miracle on a global scale.

To date, the Internet has begun to make some big changes in the business practices in selected industries . For instance, electronic commerce has taken over 2.2 percent of the U.S. leisure travel industry. In the near future, the Internet has the potential to transform many other industries . For instance, the USD 71.6 billion furniture business is a possibility. Logistics is a key for success in this industry. Consumers would expect timely delivery and a mechanism for rejecting and returning merchandise if it didn’t meet expectations.

What is the future of electronic commerce? As in any field of human endeavor, the future is very difficult to predict. We describe the promise of electronic commerce. As reflected in the stock prices of e-commerce enterprises, the future of electronic commerce seems very bright indeed. In this book, we present some trends to come, by taking a business strategy approach.

One way to try to understand the future of the Internet is by comparing it to other (communication) technologies that have transformed the world in past decades (e.g., television and radio). Another way to understand the Internet is to consider the attributes that make it unique. These factors include the following:

- the speed of information transfer and the increasing speed of economic

transactions; - the time compression of business cycles;

- the influence of interactivity;

- the power and effectiveness of networks;

- opportunities for globalization.

The Internet is complex. We adopt an interdisciplinary approach to study this new technology and its strategic ramifications. Specifically, we concentrate on the following three disciplines: management information systems, marketing, and business strategy. As described at the outset of this chapter, we show how the Internet is relevant for communicating with multiple stakeholder groups. Nonetheless, since we approach electronic commerce from a marketing perspective, we concentrate especially on consumers (including business consumers) and how knowledge about their perspectives can be used to fashion effective business strategies. We focus on all aspects of electronic commerce (e.g., technology, intranets, extranets), but we focus particular attention on the Internet and its multi-media component, the Web.

For a variety of reasons, it is not possible to present a single model to describe the possibilities of electronic commerce. For that reason, we present multiple models in the following chapters. Some firms (e.g., Coca-Cola) find it virtually impossible to sell products on the Internet. For these firms, the Internet is primarily an information medium, a place to communicate brand or corporate image. For other firms (e.g., Microsoft), the Internet is both a communication medium and a way of delivering products (e.g., software) and services (e.g., on-line advice for users). In brief, one business model cannot simultaneously describe the opportunities and threats that are faced in the soft drink and software industries. The following section provides more details about this book and the contents of the remaining chapters.

Conclusion

As the prior outline clearly illustrates, this is a book about electronic commerce strategy. We focus on the major issues that challenge every serious thinker about the impact of the Internet on the future of business.

Cases

Dutta, S., and A. De Meyer. 1998. E*trade, Charles Schwab and Yahoo!: the transformation of on-line brokerage . Fontainebleau, France: INSEAD. ECCH 698-029-1.

Galal, H. 1995. Verifone: The transaction automation company. Harvard Business School, 9-195-088.

McKeown, P. G., & Watson, R. T. (1999). Manheim Auctions. Communications of the AIS, 1(20), 1-20.

Vandermerwe, S., and M. Taishoff. 1998. Amazon.com: marketing a new electronic go-between service provider . London, U.K.: Imperial College. ECCH 598-069-1

References

Ansoff, H. I. 1957. Strategies for diversification. Harvard Business Review 35 (2):113-124.

Child, J. 1987. Information technology, organizations, and the response to strategic challenges. California Management Review 30 (1):33-50.

Quelch, J. A., and L. R. Klein. 1996. The Internet and international marketing. Sloan Management Review 37 (3):60-75.

Zinkhan, G. M. 1986. Copy testing industrial advertising: methods and measure. In Business marketing , edited by A. G. Woodside. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 259-280.