7.3 Records & Reporting

Election officials keep meticulous records. Accurate records are essential for maintaining an accurate count (and potential recounts) and for ensuring public confidence in the electoral process. For instance, ballot reconciliation is a process used to verify that the number of ballots issued equals the number of ballots cast. Election officials also track ballots that were spoiled or damaged to ensure that the correct number of ballots is accounted for (ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, n.d.-i)

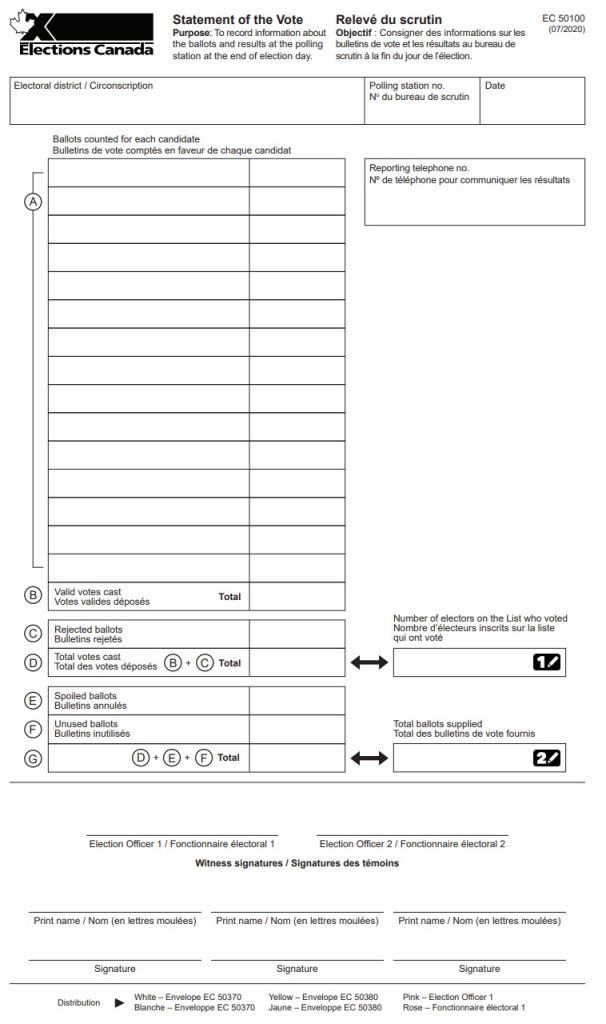

After tabulating is complete, the results are sent to a central reporting authority, such as a chief returning officer. This can happen electronically by uploading totals to an Election Management System (MIT, 2021). In Canada, reporting is done using a statement of the vote form (Elections Canada, 2025, March 7) shown in the image below.

Image Description

This is a sample statement of the vote for a polling station, which is completed by the deputy returning officer after the ballots are counted. It lists the number of votes cast for each candidate as well as the number of electors who voted, total valid votes, rejected ballots, spoiled ballots and unused ballots. It captures basic tracking information and must be signed by two election officers. It may be signed by candidates’ representatives.

Central election administrators will compile and verify results to ensure that totals from all voting locations have been added correctly. In American elections, this process is called a canvas, which “refers to the collection and reconciliation of all ballot materials used during an election” (Thomas & Weil, 2021).

Communicating Interim Results

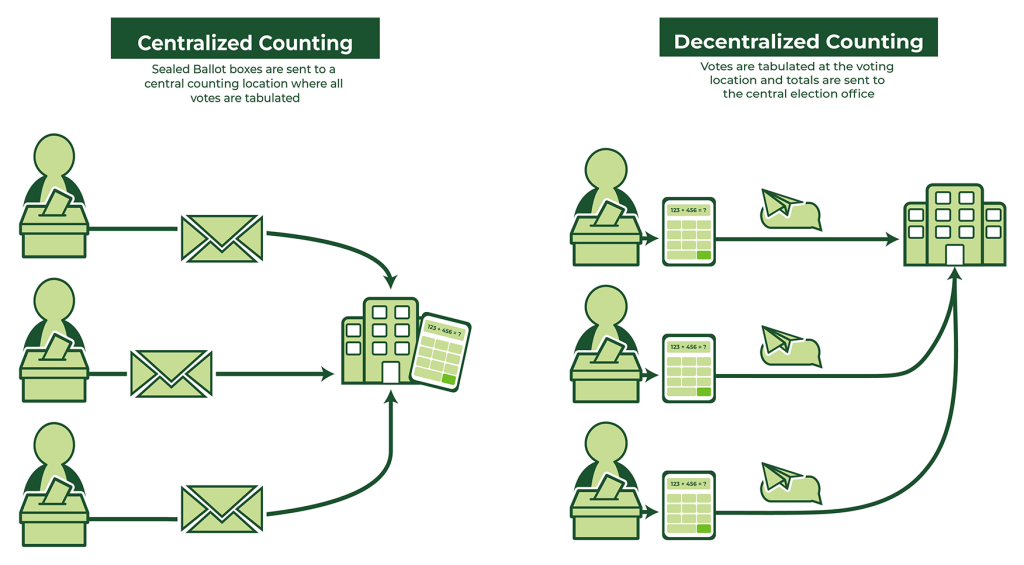

The communication process for publishing results will differ depending on whether the tabulating happens locally or at a central location. If votes are counted locally at the voting location, poll workers will tabulate the votes and communicate the totals to the Electoral Management Body (EMB) for publication, often on a government website. Alternatively, unopened ballot boxes might be transported to a central counting facility where the votes are tabulated before being sent to the EMB.

Image Description

On the left, titled “Centralized Counting,” voters place ballots into sealed envelopes, which are sent to a central counting location where all votes are tabulated. Arrows point from three voter stations to a central building with a calculator icon, indicating centralized tabulation.

On the right, titled “Decentralized Counting,” votes are tabulated at each voting location using calculators, and the totals are then electronically sent to a central election office. Arrows flow from each voting station with a calculator and paper plane icon to a central building, indicating decentralized reporting of totals.

The results published on election night are only preliminary. Outstanding absentee ballots may need to be counted, and any recounts must be performed. For election officials, the election night results will – ideally – include as many votes as possible. It’s also imperative for the EMB and news outlets to include cautionary language emphasizing the preliminary nature of the results (ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, n.d.-i). The public may begin to question the legitimacy of the counting process if there are large discrepancies between the interim totals and the final results.

Communicating Final Results

Before the digital age, official election results were made available by posting a paper printout on an office door or bulletin board, and relying on a news wire service, such as the Associated Press (AP) for distribution (MIT, 2021). Today, election results are primarily shared digitally or posted on election websites. The final results may take several weeks to determine, which is necessary for allowing sufficient time to verify the vote totals submitted, to conclude any recounts, and to physically receive all ballots (ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, n.d.-i).

Before the digital age, official election results were made available by posting a paper printout on an office door or bulletin board, and relying on a news wire service, such as the Associated Press (AP) for distribution (MIT, 2021). Today, election results are primarily shared digitally or posted on election websites. The final results may take several weeks to determine, which is necessary for allowing sufficient time to verify the vote totals submitted, to conclude any recounts, and to physically receive all ballots (ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, n.d.-i).