Things That Do Not Belong In Your Speech: Curse Words, ISTS, Slang, and Bafflegab

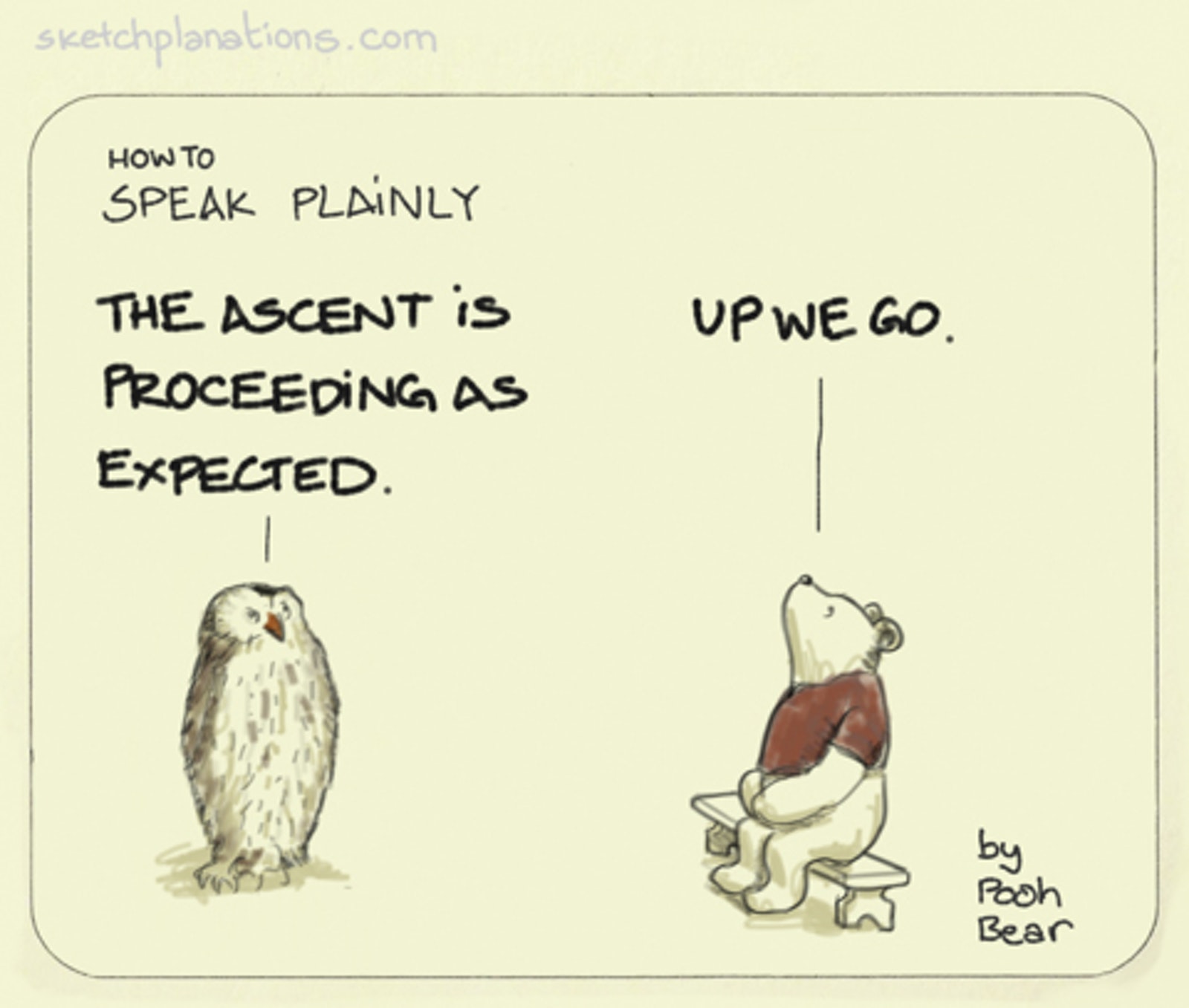

Sometimes big words can mean so little.

I’m so sorry. If you were my student the semester after I graduated from graduate school, I really need to apologize. I need to apologize for using my graduate student vocabulary in your freshman course. I need to apologize for telling you about the detailed educational philosophy behind everything I did. I am so sorry I used the words “pedagogy” and “learning objectives” in the lectures about how to give a good speech.

In my defense, most new teachers do this. I can remember having a teacher who was finishing up her dissertation–she baffled me with her brilliant vocabulary and impressed me with her cerebral lectures. I have no idea what she said, but at least she sounded smart while saying it.

In this chapter, I am going to talk about why you should avoid big words and specialty language. In fact, I am going to share with you many other things you should avoid in your speech as you seek to get your point across to your audience.

Beware of the Curse of Knowledge

When I was in graduate school I suffered from the curse of knowledge. Actor and communication expert, Alan Alda in his book, If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on my Face says,

Once we know something, it’s hard to unknow it, to remember what it’s like to be a beginner. It keeps us from considering the listener. Using shorthand that is incomprehensible to the other person, or referring to a process they’re unfamiliar with, we lock them out, and we don’t even realize it because we can’t believe we are the only person who knows this stuff.

The problem is people are “unable to ignore the additional information they possess,” according to economists Camerer, Loewenstein, and Weber. These researchers questioned whether or not it was beneficial to know more when it came to sales. In short, their finding was that it is not beneficial. If you know too much information, it is hard not to use that information and too much information can be overwhelming. It is hard to remember what it was like before you had that knowledge. It is hard to put yourself in the mind of your audience who does not understand. Sometimes, knowledge is a curse.

Go to one of your friends and ask them to help you with a little experiment. Ask them to “guess this song” and then tap out the tune to the “Star-Spangled Banner” with your finger. Did they guess it? Chances are they can’t. Try another common song like “happy birthday.” Chances are that as the tapper, you are going to get frustrated because it is so obvious and so easy to guess but most people just won’t get it.

This is a mock-up of what a graduate student at Stanford did. Elizabeth Newton first asked how likely it would be that the person listening would guess the tapped song. They predicted the odds were about 50 percent. The guessers got it right only 2.5% of the time. What seemed obvious to the tapper was not obvious to the listener. You can see where this is going. To bring it back to the earlier study, a CEO who says she is “unlocking shareholder value” might just sound like random tapping to those unfamiliar with the phrase. Sometimes, knowledge is a curse.

In your speech, you must remember what it was like to not know and use your naivete in your speech. Part of this is to avoid big words, jargon, and slang. Let’s break these down one at a time.

Avoid Big Words (unless you need to impress people at an academic conference)

Why use a three-dollar word when a two-dollar word will do? Words like facetious, discombobulation, obfuscate, and cacophony make you sound smart, but they won’t make you understood. There is a time and place for your ‘big” vocabulary, but it is rarely in your speech.

As with all things, context is key. If you are a graduate student or faculty member at an academic conference, you should whip out all those “three-dollar words.” You should also use those big words if you are called to be an expert witness. Dr. Robert Cialdini, a persuasion researcher, says professional witnesses who use big words are more persuasive. Jurors think, “That witness said an important word that I don’t understand, he must be smart. I’ll trust what he said to be true.” Since most of the time, you are not at an academic conference, nor are you called to be an expert witness, you should stick with the simple words.

Side note: If you plan on using a big word you are not familiar with, look up the proper pronunciation of the word. Practice saying the word multiple times and put a pronunciation key in your notes. Nothing kills your credibility like stumbling over big words.

Avoid Bafflegab (Eschew Obfuscation)

According to Milton Smith, originator of the term bafflegab said,

Bafflegab is multiloquence characterized by consummate interfusion of circumlocution or periphrasis, inscrutability, incognizability, and other familiar manifestations of abstruse expatiation commonly used for promulgations implementing procrustean determinations by governmental bodies.

In short, it is using fancy words used to sound smart or to deliberately confuse your audience. William Lutz called it this inflated language. Most of the time, your audience is confused and not impressed. My dad used to tell me not to confuse my audience or I would be “up the proverbial tributary of deification without and adequate means of propulsion.”

Consider This When Speaking English to a Group of International People

National Public Radio shared a program about the challenges to non-American English speakers. Consider the scenario where speakers from Germany, South Korea, Nigeria, and France are having a productive conversation in English. An American enters the conversation and says, “let’s take a holistic approach” and “you hit it out of the park”. Suddenly, understanding goes down. Research indicates, when an American enters the conversation, understanding goes down because they tend to use simple words and phrases that can be challenging for nonnative speakers.

Prepone That! Your Accent Is Funny! Readers Share Their ESL Stories

Sergio Serrano is a professor of engineering science and applied mathematics at Temple University. Having lived in North America for 40 years after growing up in Bogotá, Colombia, Serrano shares his experience speaking English in academic settings and dealing with accent stereotypes.

Sergio Serrano has participated in many international scientific conferences across the globe. “In a typical situation, a group of foreign researchers are discussing a complex technical issue with very precise and elaborate formal English,” Serrano says, “until an American joins the group.”

In our previous article about speaking English, we discussed research that found understanding goes down in a room of nonnative speakers when a native English speaker joins the conversation. The research found that communication is inhibited in part due to native speakers’ use of language not held in common, like culturally specific idioms.

But this scenario doesn’t fit with Serrano’s experiences of English, where nonnative English speakers who learned the language in a classroom are often more educated on grammar rules and complex technical terms than American native speakers.

For Serrano, when an American joins in a conversation among nonnative speaking scientists, the conversation does falter, but not because the American’s language is too complex.

“On the contrary, communication ends because [the foreign researchers] cannot explain to the American, in simple language, the advanced topics they were discussing. Yet, the American takes over the conversation.”

Complete excerpt from:

McCusker, C. (2021). Prepone that! Your accent is funny! Readers share their ESL stories. Goats and Soda: Stories of life in a Changing World, NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/05/16/995963311/prepone-that-your-accent-is-funny-readers-share-their-esl-stories

Avoid Jargon (well, mostly)

Jargon is the specialized language of a group or profession. If you are part of the group and speaking to an audience made up of people from that group, then you should use jargon, in fact, it would be hard for you not to. If, however, there are outsiders in the audience, you should be sure to define unknown terms or exclude them altogether.

Just for fun, I asked my social circle to come up with jargon they might hear in their specialty, and here are a few of their replies.

- Contras open to double f at the end of that crescendo.

(Tubas get very loud after the buildup–Marching band directions) - Make sure you maintain cover when that pinwheel crosses the yard line.

(Make sure the drumline is lined up front to back as it spins over the football field’s yard line–Drum Corp directions) - Soon, you will ETS and will no longer eat MRE’s and wear BDU’s. (Soon you will get out of the military and no longer have to eat dehydrated food and wear soldier uniforms–US Army.)

- The scuttlebutt is we won’t endex until next week. (Rumor has it this operation won’t be over until next week–Marines)

Double Speak

William Lutz, the American linguist, coined the term doublespeak to mean language that deliberately obscures, disguises, distorts, or reverses the meaning of words.

“Doublespeak is a matter of intent. You can identify doublespeak by looking at who is saying what to whom, under what conditions and circumstances, with what intent, and what result. If a politician stands up and speaks to you and says, ‘I am giving you exactly what I believe,’ and then turns around and does the opposite, then you’ve got a pretty good yardstick. She was pretending to tell me something, and it turns out it wasn’t what she meant at all, she meant something different,” says Mr. Lutz.

Lutz claims doublespeak is distorting the language to the benefit of the speaker. Let’s talk about each of these in speechmaking: Jargon, euphemism, bureaucratese, and inflated language.

Jargon: We talked about that already as the special language of a group. If you are an insider, you should use it, but when you are not, you should avoid it altogether.

Euphemism: Words that are used in place of something offensive or unpleasant. When it comes to speechmaking, euphemisms aren’t always bad. For example, when giving a eulogy, most people prefer to say, “passed away” or “went on to a better place.” That type of euphemism is a form of politeness it moves on to be doublespeak when it is used to mislead. Lutz points to the pentagon using the phrase, “Incontinent ordinance” to mean bombs that fall on civilian targets, and “unlawful arbitrary detention” which means to be held without a trial. He also uses the example from when a bill was proposed asking for money for a “radiation enhancement device” it was talking about buying a neutron bomb.

Inflated Language: Inflated language is designed to make the simple seem complex or to give an air of importance to things, or situations. Instead of using the phrase invasion, the pentagon chose to say they had “predawn verticle insertion.” Sarcastic teachers will sometimes tell their students to “eschew obfuscation” (eshew=avoid; obfuscation-confusing and ambiguous language).

Bureaucratese: Lutz nicknames this “gobbledygook.” In short, it is piling on of words by either giving a bunch of large words or just a large quantity of words. Alan Greenspan testified before that Senate Committee, “It is a tricky problem to find the particular calibration in timing that would be appropriate to stem the acceleration in risk premiums created by falling incomes without prematurely aborting the decline in the inflation-generated risk premiums.”

Avoid Slang (Most of the time)

Slang is the informal language of a particular group. Because it is seen as “informal,” it should be avoided in formal speeches like career speeches, academic speeches, and professional speeches. In less formal speeches, slang can be useful. If you are an insider to the group, slang can build credibility. Studies found that it created a more supportive classroom climate when a teacher used positive slang such as “cool” and “awesome,”

Use slang sparingly and with intent. Slang that is doesn’t fit the audience and context may rob you of your credibility and muddle the message’s meaning. When it comes to slang when in doubt, don’t.

Avoid Cliches (Like the Plague)

Clichés are overused expressions that have lost their meaning over time. Cliches can make you seem too lazy to come up with concrete words and some people find them annoying. If you are writing a formal essay, all experts say to avoid cliches. If you are making a formal academic presentation, avoid cliches. In speeches, sometimes they work, but other times the meaning gets lost.

Cliches are culturally bound so they may be misunderstood. Let’s take the cliche, “The devil’s in the details.” Does that mean details are bad like the devil is bad? Or does it mean the reason there are details is that the devil makes us have them? If you don’t know the actual meaning of the cliche it can be really confusing.

(The devils in the details mean that the details may take more effort than you think or there may be hidden problems).

Like everything in this chapter, context and audience matter. Some cliches may be just right for an audience so that is why researching your audience is important.

Avoid Cusswords (Most of the d@#! time)

To cuss or not to cuss, that is the question?

If you would have asked me that question, ten years ago, I would have advised you that under no circumstances should you ever swear in a speech. I have to be honest here, however, some of my favorite speeches use swear words. Dr. Randy Pausch says curse words in the Last Lecture and Dr. Jerry Harvey’s lecture on Abilene Paradox just would not be the same without him telling you the cuss word spoken by his grandfather. When speakers say cuss words, they risk losing credibility points with the audience. When there are credibility points to spare, a well-placed swear word may actually make them seem more approachable. If, however, you are a speaker who is on the same level as your audience, you might not want to risk those credibility points.

Instead of thinking of swearing as uniformly harmful or morally wrong, more meaningful information about swearing can be obtained by asking what communication goals swearing achieves. Timothy Jay and Kristin Janschewitz, researchers who study taboo language.

If you want to swear in your speech, ask yourself “Why? What do I want to achieve?” Your goal as a speaker should be to get your message across to your audience. With that in mind, you should decide if there is someone in your audience who would be offended by your word and if that offense would cause them not to listen to your message. If that is the case, you should leave the swear word out.

What Do You Think of a College Teacher Who Swears?

Researchers looked at what college students thought when their teachers said swear words. The impact on students was influenced by whether teachers were swearing to be funny, swearing at a person, or swearing about the class content. As you can imagine, students did not like a teacher to swear at students. The other types of swearing caused mixed reactions. When asked, students felt like classroom swearing, made them feel:

- Closer to course content.

- More alert.

- Slightly offended or uncomfortable.

- Like the teachers was trying too hard.

- Like teacher seemed less in control.

- No change in how they felt about the teacher.

Students thought that swearing was part of the instructor’s personality tended to cause them to perceive the teacher as verbally aggressive a trait associated with diminished student learning and student satisfaction.

Reflect on a college teacher you had that said curse words in class, did you like them more? Did they lose credibility points? Did you find them more approachable?

The Profanity President: Trump’s Four-Letter Vocabulary

Read this excerpt from the New York Times about President Trump’s cusswords in speeches. As you read, ask yourself whether you think swearing hurt or helped his credibility. If you were his political advisor, what would you tell him to do?

In a single speech on Friday alone, he managed to throw out a “hell,” an “ass” and a couple of “bullshits” for good measure. In the course of just one rally in Panama City Beach, Fla., earlier this month, he tossed out 10 “hells,” three “damns” and a “crap.” The audiences did not seem to mind. They cheered and whooped and applauded.

“I’d say swearing is part of his appeal,” said Melissa Mohr, the author of “Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing,” published in 2013. “It helps create the impression that he is saying what he thinks, ‘telling it like it is.’ We tend to believe people when they swear, because we interpret these words as a sign of strong emotions. In his case, the emotion is often powerful anger, which his supporters seem to love.” New York Times

You are the political advisor, what would you advise him to do?

Can you think of other examples of swearing in political speeches?

How did reading those presidential swear words impact you?

Avoid the ISTS

Ists do not belong in your speech. Avoid racist, sexist, agist, heterosexist, ableist language. And while you are at it, make sure you know the preferred name for people groups.

The “right” word to use changes over time and changes based on context. When I started to write this chapter, I thought I would make a list of what words to say and what words not to say. It was going to be the definitive list of what to call people. I quickly realized that by the time this book was published, those words might change. So, now I am telling you that knowing the right term is an important part of your speech research.

As a speaker, it is your responsibility to use inclusive language and to choose your words in a way your audience feels included and respectful. It is your responsibility to research your subject and your audience and this includes how to use respectful language.

I found this guide from the University of South Carolina helpful: Inclusive Language Guide from University of South Carolina Aiken.

Discuss This

Read one of these articles and discuss how it applies to word choice and public speaking.

Words That Significantly Hurt Politicians

The wrong word at the wrong time to the wrong audience can be problematic for a speaker. For a politician, it can be career changing. Here are a few examples of times politicians got it wrong.

If you are easily offended, you might skip this section.

You People

“Good and decent people all over this country, and particularly you folks, have got bars on windows. Drug use is absolutely devastating to our country and absolutely devastating to you and your people.” Ross Perot, presidential candidate.

Basket of Deplorables

“You know, to just be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump’s supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables. Right? The racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic — you name it. And unfortunately, there are people like that. And he has lifted them up.” Hillary Clinton, Democratic candidate for the Presidency.

Legitimate Rape

In an interview for KTVI-TC, the question was posed “An abortion could be considered in the case of a tubal pregnancy, what about in the case of rape?” Politician Todd Akin replied. “If it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down. But let’s assume that maybe that didn’t work or something: I think there should be some punishment, but the punishment ought to be of the rapist, and not attacking the child.” Todd Akin, Republican candidate for the Senate.

I’m Not a Witch

In an interview, Christina O’Donnel told Maher that she dabbled into witchcraft but never joined a coven. Later she made a campaign video: “I’m not a witch. I’m nothing you’ve heard. I’m you. None of us are perfect, but none of us can be happy with what we see all around us: politicians who think spending, trading favors, and back-room deals are the ways to stay in office. I’ll go to Washington and do what you’d do.” Republican Candadate, Christine McDonnell

(Fun fact, political coaches suggest you never repeat the accusation even to say I’m not because it reinforces it and makes it stick in the minds of listeners.)

Extremism

“I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” Senator Barry Goldwater. (To use the word extremist always carries negative connotations.)

You Ain’t Black

Joe Biden: “Well I tell you what, if you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, then you ain’t black.” Joe Biden, Democratic presidential candidate.

Crisis of Confidence

It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation. The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America. The confidence that we have always had as a people is not simply some romantic dream or a proverb in a dusty book that we read just on the Fourth of July… Our people are losing that faith, not only in government itself but in the ability as citizens to serve as the ultimate rulers and shapers of our democracy. President Jimmy Carter (Carter thought he would be respected for the honesty but all the negative words, made people feel bad).

The Scream That Killed a Political Campaign

Anytime political mishaps come up, the Dean Scream is mentioned. It was the scream that seriously damaged his political campaign. This chapter is really about what words not to say, in this case, it is what sound not to make–beyond words.

Watch 2004: The scream that doomed Howard Dean (1 mins) on YouTube

Video source: CNN. (2013, July 31). 2004: The scream that doomed Howard Dean [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/l6i-gYRAwM0

Avoid Powerless Language (It really makes you sound smart, don’t you think?)

Powerless language consists of words or phrases that weaken the language and undermine credibility. Powerless language results in the speaker being seen as less persuasive, less attractive, and less credible.

It is true that in social settings, you should be willing to use powerless language for the sake of cooperation, but in speeches, you should stick with sounding confident and powerful.

| Problem | Definition | Example statements |

|---|---|---|

| Hedges | Statements that make a phrase sound less forceful. |

|

| Hesitations | Words or sounds that are pauses in the speech like uh, um, er. |

|

| Intensifiers: | Words that do not add meaning but attempt to magnify the emotional content. |

“Substitute ‘damn’ every time you’re inclined to write ‘very’; your editor will delete it and the writing will be just as it should be.” Mark Twain |

| Taq questions | Adding questions to the end of the sentence to make an assertion sound like a question. |

It is OK to ask the audience questions. It becomes powerless language when you tag the question on so you don’t sound certain of what you are saying. |

| Disclaimers |

Information given before a statement that signals a problem, a lack of understanding, or anticipates doubts |

|

| Self Critical | Making negative statements about yourself |

|

| Uptalk | Making voice go up at the end of a sentence making it sound like a question | (no example) |

Powerless language is not always a bad thing, Dr. Fragale found that when doing group work, powerless language can make you appear more cooperative.

When people hear someone who is very confident and certain in the way that they speak, others think of that person as really dominant and ambitious and assertive, but they also think of that person as less warm, less collaborative and less cooperative. In groups that require a lot of teamwork, team members are looking for people who have good team skills, who care about other people. Those personality attributes are more important than how dominant or ambitious you are.

Oftentimes, you will have a group project that leads up to a speech. In this scenario, you should use your cooperative speech for working with the team and your assertive language in the speech.

At first glance, this whole chapter looks like it is dedicated to things to avoid. In reality, it is dedicated to getting you to think about one big thing–context. Context matters. Who makes up your audience, what the expectations of the occasion are, and who you are in relation to each will impact how you should design your speech. The most important thing in speechmaking is to figure out how to share your message in a way that the audience can listen to and receive your message.

Key Takeaways

Remember This!

- The goal of your speech is to get your message across to your audience, by knowing the context, the occasion, and the audience you can avoid things that will cause them to not want to listen.

- Your credibility can be positively or negatively affected by your choice of words.

- Always be intentional with slang, jargon, and big words. Using them or not using them by choice in a way that connects with your audience.

- Always use inclusive language and adapt your vocabulary in a way your audience will feel respected and included.

- Beware of the curse of knowledge and realize that what is easy for you to understand may not be easy for your audience so adjust your speech accordingly

Attribution & References

Except where otherwise noted, this chapter is adapted from “Things That Do Not Belong In Your Speech: Curse Words, ISTS, Slang, and Bafflegab” In Advanced Public Speaking by Lynn Meade, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

References

AP. (1992). Perot calls black group ‘you people: Draws fire–some in NAACP audience welcome unpolished speech. The Seattle Times. https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=19920712&slug=1501684

Alda, A. (2017). If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face: My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating. Random House.

Baker, P. (2019). The profanity president: Trump’s four-letter vocabulary. The New York Times. https://search.proquest.com/newspapers/profanity-president-trump-s-four-letter/docview/2244183119/se-2?accountid=8361

BBC. (2012). US row over Congressman Todd Akin’s rape remark. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-19319240

Camerer, C., Loewenstein, G., & Weber, M. (1989). The curse of knowledge in economic settings: An experimental analysis. (1989). Journal of Political Economy 97(5). https://doi.org/10.1086/261651

Cialdini, R. (1993). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. William Morrow.

Generous, M. A., & Houser, M. L. (2019). “Oh, st! did I just swear in class?”: Using emotional response theory to understand the role of instructor swearing in the college classroom. Communication Quarterly, 67(2), 178-198. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2019.1573200

Generous, M. & Frei, S. & Houser, M. (2014). When an instructor swears in class: Functions and targets of instructor swearing from college students’ retrospective accounts. Communication Reports. 28. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2014.927518

Gura, S. (2010). ‘I’m not a witch,” Republican candidate Christine O’Donnell tells Delaware voters. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2010/10/05/130353168/-i-m-not-a-witch-republican-senate-candidate-christine-o-donnell-says-in-new-ad?fbclid=IwAR3UsTaVFnHkH4nGk8rmjblbR9ZlbY-3zIKLaydfjdHlQJM0a-mhufvLAno

(1996) Student perceptions of teachers’ use of language: The effects of powerful and powerless language on impression formation and uncertainty. Communication Education 45(1), 16-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529609379029

Heath, C. and Heath, D. (2008). Made to stick: Why some ideas survive and others die. New York, Random House

Heath, C & Heath, D. (2006). The curse of knowledge. Harvard Business Review https://hbr.org/2006/12/the-curse-of-knowledge.

Hicks, K. (2020). Biden says he regrets ‘you ain’t Black; comment: I shouldn’t have said that”. The Denver Channel. https://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/election-2020/biden-says-he-regrets-you-aint-black-comment-i-shouldnt-have-said-that

Heyne, R. L. (2016). “Fired up about education”: A quantitative exploration of positive and negative slang. Theses and Dissertations. 572.

https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/572 http://doi.org/10.30707/ETD2016.Heyne.R

Hogarth, R. M., & Reder, M.W., eds. (1986). The behavioral foundations of economic theory. Supplement to Journal of Business, 59(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X8800700214

Hosman, L. A., & Siltanen, S. A. (2011). Hedges, tag questions, message processing, and persuasion. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 30(3), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X11407169

Hosman, L. & Siltanen, S. (2006). Powerful and powerless language forms. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 25. 33-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X05284477

Jay, T. & Janschewitz, K. (2012). The science of swearing. Psychological Science. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/the-science-of-swearing

Jenkins, J. (2002). A sociolinguistically based, empirically researched pronunciation syllabus for English as an international language. Applied Linguistics, 23. 83-103. DOI:10.1093/applin/23.1.83

, C. &. (1990) Placement and frequency of powerless talk and impression formation. Communication Quarterly 38:4, 325-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463379009369770

(1987) An introduction to powerful and powerless talk in the classroom, Communication Education, 36(2), 167-172, DOI: 10.1080/03634528709378657

Kenan Flagler School of Business (2010). The power of powerless speech. https://www.kenan-flagler.unc.edu/news/the-power-of-powerless-speech/

Lepki, L. (2020). The internet’ss best list of cliches. https://prowritingaid.com/art/21/List-of-Clich%C3%A9s.aspx

Lutz, W. (1987). Language, appearance, and reality: Doublespeak in 1984. Institute of General Semantics. ETC 44(4). (no doi)

Mazer, J. P. & Hunt, S. K. (2008) “Cool” communication in the classroom: A preliminary examination of student perceptions of instructor use of positive slang, Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, 9(1), 20-28, DOI: 10.1080/17459430802400316

Mazer, J. P., & Hunt, S. K. (2008). The effects of instructor use of positive and negative slang on student motivation, affective learning, and classroom climate. Communication Research Reports, 25, 44 – 55. doi: 10.1080/08824090701831792

McCusker, C. (2021). Prepone that! Your accent is funny! Readers share their ESL stories. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2021/05/16/995963311/prepone-that-your-accent-is-funny-readers-share-their-esl-stories

PBS Frontline. (2004). Interview with Frank Luntz. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/persuaders/interviews/luntz.html

Reilly, K. (2016). Read Hillary Clinton’s ‘basket of deplorables’ remarks about Donald Trump supporters. Time Magazine. https://time.com/4486502/hillary-clinton-basket-of-deplorables-transcript/

Smith, M. (2011). Bafflegab. bafflegab.net.

Swartzman, E. (n.d.). Why doublespeak is dangerous. https://www.ericschwartzman.com/why-doublespeak-is-dangerous/

Vinson, L, Johnson, C.E., & Hackman, M.Z. (1993). Explaining the effect of powerless language use on the evaluative listening process: A theory of implicit prototypes. George Fox University Faculty Publications. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1042&context=gfsb

Weiner, T. (2010). Alexander M. Haig Jr dies at 85; was a forceful Aide to 2 Presidents. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/21/us/politics/21haig.html