Don’t Ruin a Great Presentation with Terrible Slides

The more strikingly visual your presentation is,

the more people will remember it.

And more importantly, they will remember you.

– Paul Arden

Creative Director of Advertising Company Satchi and Satchi

Professor Lynn Meade tells this story:

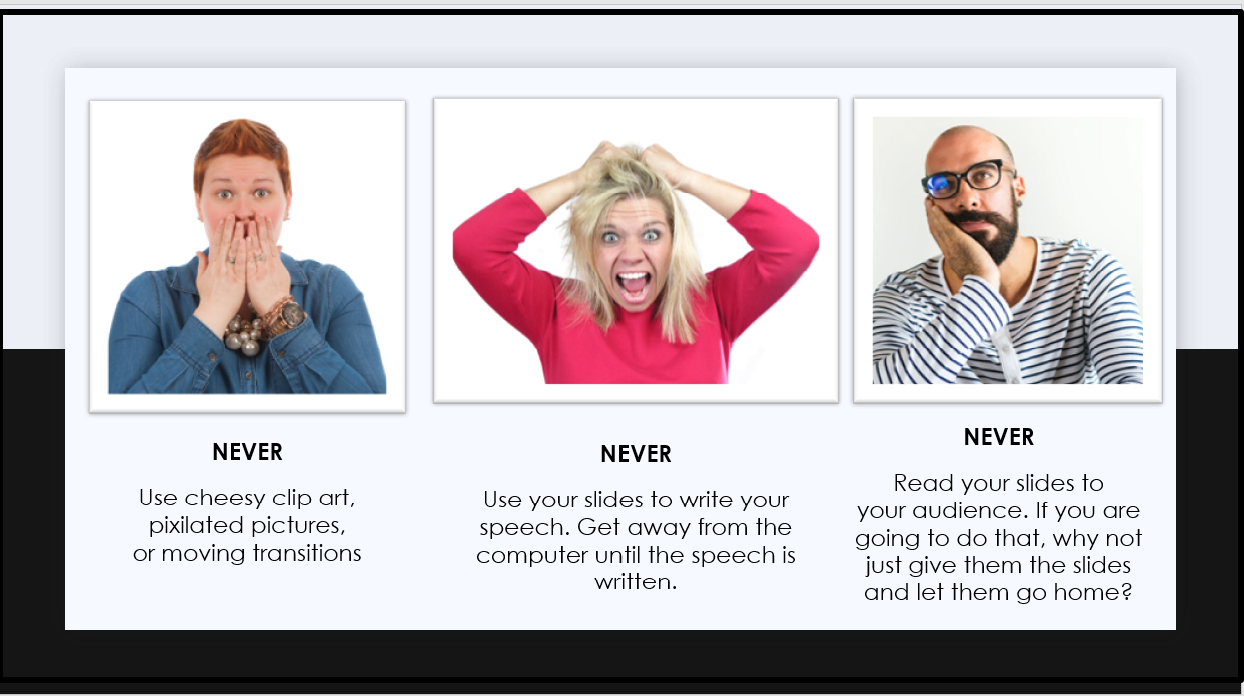

“The speaker was a master in his field which is why he was chosen to speak. He was brilliant, he was motivated to share his ideas, and he was great at conversation. The only problem was he was the most boring speaker I have ever heard. He stood at the front of the room and read presentation slides to us for two hours. He rarely looked at the audience. It was the longest two hours of any conference I have ever attended!”

Chances are you have had a similar experience. A speaker has ridiculous amounts of text on a slide and then stands there and reads it to you. Unfortunately for all of us, a lot of college classes are that way. In fact, most of us learned about how to use slides by seeing our teachers use them–poorly.

The use of electronic slides–PowerPoint, Presenter, Google Slides, Prezi—is pervasive. Sixty-seven percent of college students reported that instructors used PowerPoint; and of these instructors, 95% used this software all or most of the time. Numerous articles chide that presentation slides might be the death of education.

Many successful speakers have shunned slides altogether. Chris Anderson, head of TED, the highly successful group that leads TED Talks, highlights at least of third of the most viewed TED talks do not use any slides whatsoever.

The Most Important Questions of All

- Do I need slides?

- If I need slides, what does the audience need to get from those slides?

If you sit at your computer and you open your presentation software and begin writing your speech on your slides, you are making a slide show, not a speech. A good speaker always considers what the audience needs to hear and then uses slides to offer visual support to help the audience understand. If you start with the slides, you’ve got it backward.

Slides are Good Because They…

- Can create credibility. (Many people expect you to use slides and meeting that expectation gives you credibility.

- Help focus the audience’s attention.

- Help the audience visualize concepts.

- Help people take organized notes of a talk.

- Helps the speaker stay on track.

- Provides aesthetic appeal.

- Show something that may be hard to describe.

Slides are Bad Because They…

- Can distract from what the speaker is saying.

- Can hurt the speaker’s credibility when poorly constructed.

- Can cause people to mindlessly take notes without thinking about the content.

- Can be boring…especially when a speaker stands up there and simply reads the slides to an audience.

- Can lead to passive listening when a teacher uses them in the classroom and give the students a copy of the slides.

Rules for Slides

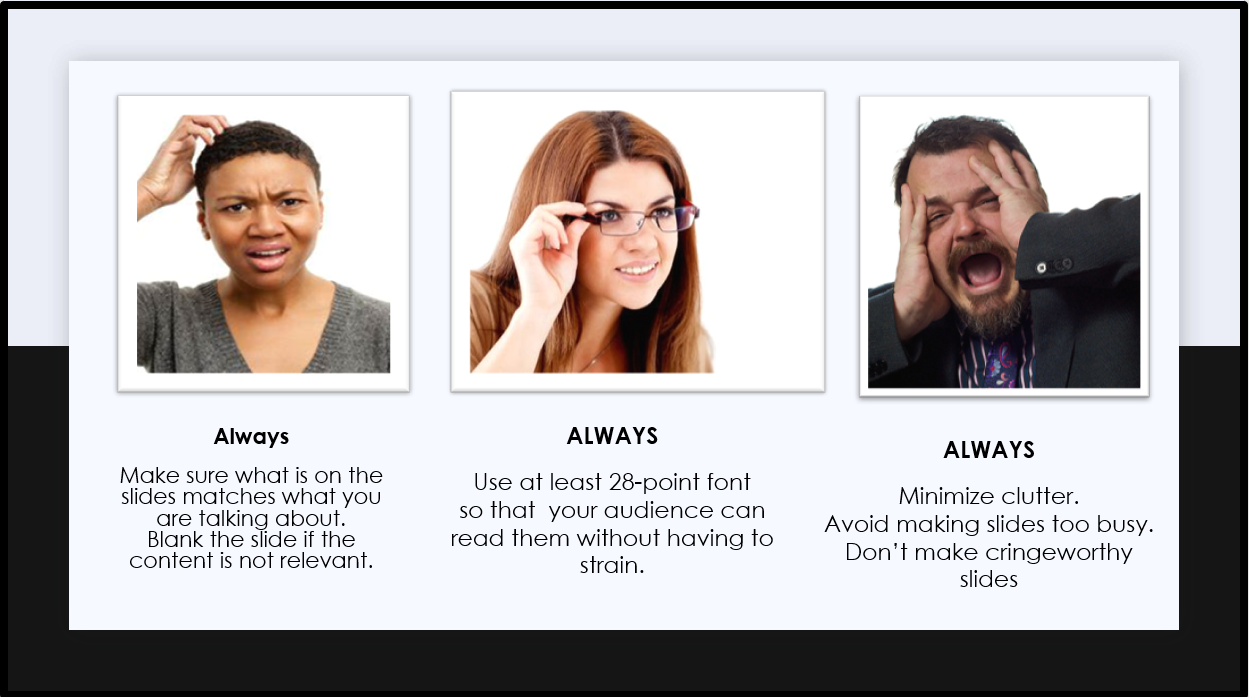

Write Your Speech First

As mentioned in the introduction, one of the most important things you can do when preparing your speech is to get away from your slide software. Under no circumstance should you open your slide software (PowerPoint, Presenter, Google slides, Prezi, Keynote, etc.) until your speech is complete and you have made a plan for what visuals the audience needs to see.

Keep Text to A Minimum

No more than six words across and six words down. Chris Anderson of TED specifies,

Even when a text slide is simple, it may be indirectly stealing your thunder. Instead of a slide that reads: A black hole is an object so massive that no light can escape from it, you’d do better with one that reads: How black is a black hole? Then you’d give the information from that original slide in spoken form. That way, the slide teases the audience’s curiosity and makes your words more interesting, not less.

Offer One Idea to a Slide

You can keep text to a minimum by limiting ideas to one per slide. Audience members should be able to glance quickly–about 3 seconds–and get all the information. It is better to have a lot of slides where each has only one idea per slide than it is to have one slide with a list of ideas. Nancy Duarte, communication coach, reminds us that if you have too many words, it is no longer a visual aid but a teleprompter. Estimate approximately how long it will take an audience member to read your slide by timing yourself reading the slide backward.

Think of your slides as billboards. When people drive, they only briefly take their eyes off their main focus — the road — to process billboard information. Similarly, your audience should focus intently on what you’re saying, looking only briefly at your slides when you display them. Nancy Duarte

Get Rid of the Title (Most of the time)

Most of the time, a title on each slide is not needed. You, the speaker, will say what the content is about; no need to read it–it is just distracting.

Reduce Cognitive Load

It is better to help the audience focus on the main point in the slide. By keeping things simple, it reduces the audience’s cognitive resources. There are several ways you can reduce cognitive load.

- Avoid busy backgrounds they can drain mental energy.

- Eliminate unneeded titles.

- Use basic, easy-to-read font.

- Ask yourself if the company logo or school banner is needed on the slide or if it just becomes one more thing.

- Keep background colors consistent

- Format photos and illustrations in the same style.

Use Pictures Instead of Words When Possible

People retain more information when what they see on the screen supports the message they are hearing.

We are incredible at remembering pictures.

Hear a piece of information,

and three days later you’ll remember 10% of it. A

dd a picture and you’ll remember 65%.

John Medina, author of Brain Rules.

Learning Recall Related to Type of Presentation

| Presentation | Ability to recall after 3 hours | Ability to recall after 3 days |

|---|---|---|

| Spoken lecture | 25% | 10-20% |

| Written (reading) | 72% | 10% |

| Visual and verbal (illustrated lecture) | 80% | 65% |

Avoid Distracting Slide Transitions

There is rarely a time when you should use the transition feature of the software. Things that twirl, cube, swap, and swoosh rarely help the audience to focus on your idea. Most of the time, they are just cheesy and distracting. Three transitions that can be used with a level of professionalism are cut, fade, and dissolve. The easiest rule is if you do not have a reason for a transition, don’t do it.

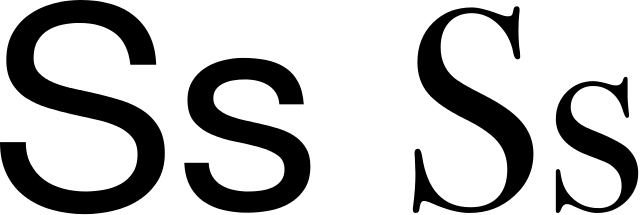

Use Easy-to-Read, Plain Font

Use 28-point font and larger. Do not use more than three different sizes and make the size variants purposeful. It is best to stick with a plain, sans-serif font such as Helvetica, Arial, or Tahoma. There are two types of font, serif (with fancy tails) and san serif (without fancy tails). The Plain, san serif font is easiest to read when projected.

Go For High Contrast

Always go for the highest contrast. I recently attended a special event and the speaker projected his side and then looked back at it surprised and said, “Sorry, you can’t see the red letters.” The speaker had attempted to put red letters on a black ground–this is always a no-no because it rarely shows well. It is best to pick a dark blue or back background and put white or yellow letters on it. You can also use a white or yellow background with dark black or blue letters (While JP Philips in the video Death by PowerPoint -below- advises against it, it is still a professional standard).

Use Minimal Bullets

If you do have bullet points, make sure you have more than one point because let’s face it, bullet points are for making lists and one point does not make a list. In addition, you should never have more than six bullet points because then you would have too much stuff on your slide.

Bullets belong to the Godfather.

Avoid them at all costs.

Dashes belong at the Olympics,

not at the beginning of the text.Chris Anderson, TED Talks

While I’m not sure I fully support eliminating all bullets, I do warn you to use them sparingly.

Use Blank Slides

You do not always have to have a slide behind you. Insert black, blank slides between points when you need to talk to the audience without the distraction of a visual.

Have a Backup Plan

Technology is evil and is the enemy of all that is good. It will crash on you. You should always have a backup plan and you should always be prepared to speak even if your slides do not work. You should always have notecards or print out your slides to reference. Then, if the projector bulb goes out or the computer crashes, you can still make your presentation.

Test Your Slide Show, Videos, and Clicker/Remote

You should always practice using your slides. It is helpful to test out your presentation on your friends or trusted colleague and ask them to give you feedback. When you get to the place where you will give your presentation, it is a good idea to pull up your slides and make sure they work with the clicker/remote. It is a good idea to carry extra batteries with you too. Test the volume of your videos and make sure they play properly. Finally, make sure you know where the audio-visual person will be in case you have any problems. If you are a student, have a friend who can come up and fix your slides while you keep your speech going.

Avoid the Laser Pointer

A laser pointer highlights any shakiness you have in your hands. If you want to highlight something on a slide, use a graphic arrow.

Make Reminders on Your Notes to Change Your Slide

Many student presenters will turn on their presentation slides and during the speech forget they are there. After they conclude their speech and we have applauded, they will look back at the projector and say, “Oh, here is my visual aid,” and then will rapidly click through the seven slides they should have shown us during the speech.

To avoid this, practice with your slides and mark on your notecards where to advance your slide. One way: draw an “S” in a circle and then color in the circle with a highlighter.

Point Your Body and Your Eyes Towards the Audience Not Towards the Slides

Your feet indicate where you want to go. If your feet are pointed towards the door, you are indicating you want to go out the door. Similarly, if your feet are pointed towards the back wall where your slides are located, it indicates you want to go towards your slides and not towards the audience. In short, you have turned your back on your audience. Point your feet, your hips, and your head towards the audience.

Keep your eyes on your audience and not your slides. Having brief slides helps. If you only have a few words or a nice photo on your slides, you are less tempted to stand there and read to the audience. In addition, having your notes in front of you as opposed to using your slides as your notes helps you keep pointed forward. Just remember, talk to your audience, not your slides.

Use Movement Minimally

These days, there are many different types of presentation slides. One of those is Prezi. For many (like me), the movement in Prezi creates a nauseous feeling. If you decide to use this tool, keep movement limited.

Video source: TED. (2011, May 11). The hidden power of smiling – Ron Gutman [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/U9cGdRNMdQQ

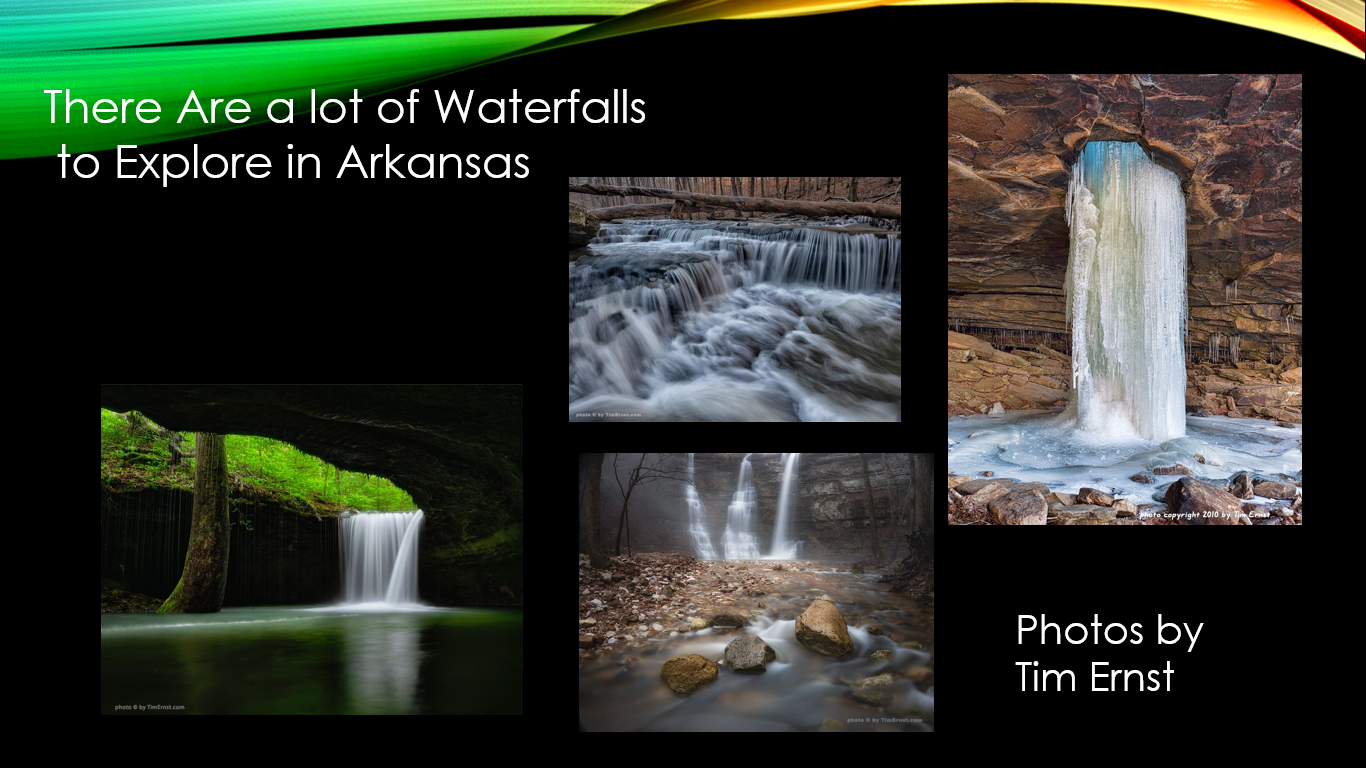

Give Credit for Visuals When Possible

When possible credit to the originator of the photo. Simply write “Photo credit: Name or originator of the photo.” Usually, 12-14-point font credit is centered under the photo or in the bottom right-hand corners. Be consistent in the way you do your citations. Citing your graphic may not look as nice as a plain slide, but it shows you have integrity, and that you give credit where it is due. Make sure you have a legal license to use the photo or they are listed as Creative Commons; better yet, do as a friend of mine does, always use your original photos.

Thoughts About Fair Dealing (Canada)

The internet makes it easy to get photos, videos, and music that you can use in your presentation. Just because it is easy to get, doesn’t mean it is legal.

Chances are you are using this textbook because you are a college student. Because your presentations are of an educational nature, many uses of external content are covered under Fair Dealing copyright laws, which means you can use small amounts of copyrighted material once for educational purposes if you give credit to the authors.

Once you graduate and work for a company, what was once considered free to use is now under a different system. For example, you may have to get permission to use someone’s photos or you may now have to pay to use a music clip.

Check your Library’s Copyright guide for information about student use of copyrighted information. Don’t hesitate to ask for help from your Professor or the library if you have questions or concerns.

Use Photos Wisely

When using photos, it is usually best to make them full screen if the picture is the point of the visual. If they are a decoration to the point, format them so they are visually pleasing and balanced with the words. If you do use a smaller photo, use a plain background. Always use pictures with the highest resolution possible and always give photo credit. In the college classroom, students prefer pictures and “visually rich” slides if they were relevant to the content of the lecture. In addition, they preferred minimal text and limited bullet-point lists.

Don’t Do This!

What’s Wrong With This Slide?

- The background is distracting.

- There are too many photos on the slide.

- The heading is not needed–the speaker should say it.

- The photo credit is too large.

Do This Instead!

What’s Right With This Slide?

- The picture is clear and takes up most of the slide.

- No unnecessarily distracting words

- The photo credit is balanced and an appropriate size.

- No caption is needed because the speaker will tell about what it is and where it is

Want to Take Your Slide Composition to the Next Level? Check out these Resources

- To see a great explanation with examples of why certain slide layouts work, see Effective PowerPoint Slides for Business

- To see samples of good and bad use of photos on slides, check out Presentation Zen.

- To take your visual composition to the next level by using the rule of thirds to compose slides, check out the rule of thirds.

- To see the types of slides a professional designer make, check out Nolan Haim’s portfolio

Nancy Duarte: [For visuals], I think people tend to go with the easiest, fastest idea. Like, “I’m going to put a handshake in front of a globe to mean partnership!” Well, how many handshakes in front of a globe do we have to look at before we realize it’s a total cliche? Another common one — the arrow in the middle of a bullseye. Really? Everyone else is thinking that way. The slides themselves are supposed to be a mnemonic device for the audience so they can remember what you had to say. They’re not just a teleprompter for the speaker. A bullseye isn’t going to make anyone remember anything. Don’t go for the first idea. Think about the point you’re trying to make and brainstorm individual moments that you’re trying to emphasize. Think to the second, the third, the fourth idea — and by the time you get to about the tenth idea, those will be the more clever memorable things for the audience.

Watch Photos that will make you want to save the Everglades – Mac Stone (21 mins) on YouTube as he shows photos that make “You want to save the Everglades.”

Video Source: TEDx Talks. (2015, April 22). Photos that will make you want to save the Everglades – Mac Stone [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/AZDRZ9sECoE

Be in the Image but Not on the Image

Stand near your slides but don’t stand where you will be a shadow on your slides. Sometimes a presenter will stand far away from their slide causing the audience to have to bounce back and forth with their attention. On the other hand, practice with your slides at the venue and have a friend let you know where you can and cannot stand. If it is easy to stand in front of the slides, I will sometimes put tape on the floor to indicate where to stand and put a tape boundary to remind myself where not to stand.

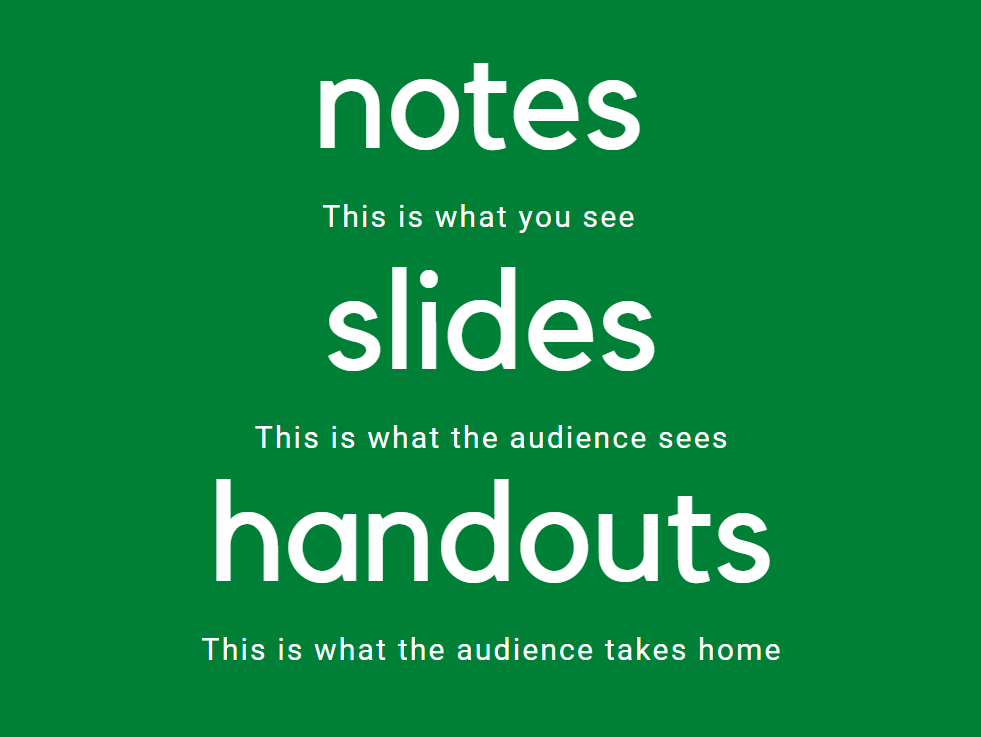

These Are Not the Same

Should I Give Out My Slides As a Handout?

One BIG mistake novice speechmakers make is they use their slides as their notes, their visual aid, and their handout. In this model, a speaker opens up the presentation software and writes their speech on the slide. When the day of the presentation comes along, the speaker stands in front of the audience and reads the slides to the audience. Finally, the speaker gives the audience members a copy of the slides to take home.

- Delivery Notes are what you look at during your presentation. They should have details about what you will say, they should have reminders for when to advance your slides, and they should have notes reminding you to project your voice or to look up.

- Slides are the projection the audience sees. They should be purposeful, brief, and concise, and designed to help listeners understand.

- Handouts are the items you give the audience to take home with them. It should provide only the information the audience needs to remember after your presentation is over.

Never, ever hand out copies of your slides, and certainly not before your presentation. That is the kiss of death. By definition since slides are “speaker support” material, they are there in support of the speaker…You. As such, they should be completely incapable of standing by themselves and are thus useless to give to your audience, where they will simply be guaranteed to be a distraction. The flip side of this is that if the slides can stand by themselves, why the heck are you up there in front of them? (David Rose as quoted in Presentation Zen)

With that said, when students spend their attention copying slides, they do not spend time listening to the lecture. Making the slides available to students to use during an educational lecture may reduce cognitive load and encourage learning. However, if the slides are so detailed the student can get all the information from the slide, then they may not attend class or they may not take any notes of their own which reduces learning. It is a delicate balance of structure but not all the content.

How To Avoid Death by PowerPoint

Excerpt from How to Avoid Death By PowerPoint

Okay, ladies and gentlemen, welcome. There is a question which has puzzled me for quite a while, and that is, why do our PowerPoints look the way they look? Or rather, how on earth, can we accept that they look the way they look? How can you do that?

And do you know what’s even more intellectually challenging for me to understand, is how can a person sit over here in this meeting room with ten others, observing this dismally bad PowerPoint filled with charts, graphical elements, page numbers, fading away five, seven minutes thinking of other things. You know the feeling, the boredom, the waste of time!? This person, after 40 minutes, he/she will stand up, a bit dazed, trotting off to his own office, coming to his own computer, flipping it up, going like: oh my god, I’ve got a presentation tomorrow, and I do have a PowerPoint to build. Now what is the chance that this person will build an equally bad PowerPoint as the one that he/she was by herself tortured by in the other conference room? Is that a big chance? Yeah. David JP Phillips, TED Speaker. How to Avoid Death By Power Point

David JP Phillip Provides This Solution

- Only put one idea per slide.

- Make spoken and projected content match. Don’t make an audience chose between listening to you or looking at your slide. Sweller and Mayer conclude there is something in our brain called the redundancy effect, and it works like this. If the audience has to pick between reading text on a slide or listening to you talk, they have a hard time focusing and cannot recall most of what was said.

- Build slides with minimal distractions. We pay attention to moving objects, signaling colors, contrast-rich objects, big objects. Build your slides with this in mind. For example, only have a large title if it is the most important, otherwise, make it smaller.

- Avoid using full sentences on slides.

- Contrast controls your focus. If you use a white background, it draws attention away from the speaker.

- Do not put too many objects on your slide. Go for six or less.

Source: Phillips, D. J. P. (2014, April 14). How to avoid death by PowerPoint [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Iwpi1Lm6dFo

Watch These Creative Uses of Slides

Notice how Tim Urban uses slides to engage the audience. Instead of long lists of words, he uses funny drawings, which results in the audience hanging on his every word.

Watch Tim Urban: Inside the mind of a master procrastinator (14 mins) on YouTube

Video source: TEDx. (2016, April 6). Tim Urban: Inside the mind of a master procrastinator [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/arj7oStGLkU

How to Put Citations in Slides

When considering the how and when of citations, it is important to consider the context of your speech. Different contexts will require different types of citations. Many speakers have ended their presentation with, “And here’s my reference page.” That has got to be the most boring way to end a speech ever! Don’t do it. There is never any reason to project your reference page for your audience to see. Depending on the context, however, you may include your reference on your slide.

|

A student in a |

A College Teacher

|

A Businessperson |

|---|---|---|

| In class, you should always verbally mention your research and you should turn in a complete reference page. Teachers will vary if they want you to include the full reference on the bottom of the slide. You should always ask the teacher. |

Typically, in graduate-level classes, students and teachers are expected to offer full citations. These are likely to be in the form of a reference page given to the audience in paper or electronic form. Each discipline is different. When in doubt, include the full reference at the bottom of a slide.

|

You will have to read into the context of this one. You should always mention any research to give you credibility but whether you put a citation on the slide will vary from place to place. When in doubt, err on the side or including the citation. Business presentations rarely include citations on photos. |

Key Takeaways

Remember This!

- Slides should always be used purposefully.

- Write your speech before making your slides.

- It is better to have many slides that each make only one point than it is to have few slides with many points.

- No more than six words across and six words down, use at least 28-point, plain (san-serif) font.

Bonus Feature

Watch a part of Sonaar Luthra’s speech for a great example of slide usage. The pictures help us to understand and remember and he avoids unnecessary words.

Watch Sonaar Luthra: Meet the water canary (4 mins) on YouTube

Video source: TED. (2012, January 16). Sonaar Luthra: Meet the water canary [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/gv1ApCmctVQ&t=27s

For those of you interested in Multi-Media Learning Principles, this chart explains how to each principle applies to good slide creation.

Multimedia Learning – Moreno and Mayer

Learning the principles behind why and how it works can help you remember how to apply them. This chart shares with you some of the best practices from multimedia research on the principle and the application of visual media.

Principle |

What does it mean? |

What does it mean

|

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Representation Principle

|

For meaningful learning to occur, both channels (verbal and visual) should be used at the same time in a way learners can connect the information from each channel. |

|

| Temporal Contiguity Principle |

Don’t be talking about one thing and have a picture up of something else. Verbal and visual content should be presented together in contiguous time. Putting words and pictures explaining the same content into working memory at the same time is beneficial. If the information is out of synch, the brain is less able to connect the information from the two inputs.

|

|

| Split Attention Principles

and |

People learn best when their attention is not split between spoken and visual words.

|

|

| Redundancy Principle |

While two channels of content that support each other can be more effective, too much can cause cognitive overload. |

|

| Coherence Principle |

Background sounds and music can overload auditory channels and distract. |

|

| Image Principle |

People do not learn better when the speaker’s image is on the screen. |

|

Attribution & References

Except where otherwise noted, this chapter is adapted from “Don’t Ruin a Great Presentation with Terrible Slides” In Advanced Public Speaking by Lynn Meade, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

References

Anderson, C. (2016). TED talks: The official TED guide to Public Speaking. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Armour, C. Schneid, S.D., & Brandl, K. (2016). Writing on the board as students’ preferred teaching modality in a physiology course. Physiology. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00130.2015

Baker, J. P., Goodboy, A.K., Bowman, N.D., & Wright, A.A. (2018). Does teaching with PowerPoint increase students’ learning? A metanalysis. Computers and Education Science Direct, 126, 376-387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.003

Bartsch, R.A. & Cobern, K.M. (2003). Effectiveness of PowerPoint presentations in lectures. Computers and Education. 41(1), 77-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0360-1315(03)00027-7

Berk, R. A. (2012). Top 10 Evidence-based Best Practices for PowerPoint in the classroom. Transformative Dialogues: Teaching & Learning Journal, 5(3), 1-7.

Brandl, K., Scheid, S., & Armour, C. (2015). Writing on the board vs PowerPoint: What do students prefer and why? Pharmacology. 29(1). https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.29.1_supplement.lb465

Chen, J. & Lin, Tsui-Fang (2008). Does downloading PowerPoint slides before the lecture leads to better student achievement. International Review of Economics Education 7 (2), 9-18, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1477-3880(15)30092-X

Copyright and Fair Use: Common Scenarios from California State University. https://csulb.libguides.com/copyrightforfaculty/scenarios

Dale E. (1969). Cone of experience, in Educational Media: Theory into Practice. Wiman RV (ed). Charles Merrill.

Duarte, N. (2008). Slide:ology: The are and science of creating great presentations. O’Reilly.

Duarte, N. (2012). Do your slides pass the glance test? https://hbr.org/2012/10/do-your-slides-pass-the-glance-test

Duarte, N. (2010). Resonate Present visual stories that transform audiences. John Wiley & Sons.

Endestad, T., Magnussen, S., & Helstrup, T. (2003). Memory for Pictures and Words following Literal and Metaphorical Decisions. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 23(2), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.2190/PNXA-4078-M1H9-8BRJ

Garr, G. (2008). Presentationzen: Simple ideas on presentation design and delivery. New Riders.

Hill, A., Arford, T., Lubitow, A., & Smollin, L. M. (2012).“I’m ambivalent about it”: The dilemmas of PowerPoint. Teaching Sociology, 40, 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X12444071

Joyce, B. & Showers, B. (1981). Transfer of training: the contributions of coaching. Journal of Education 163(2): 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205748116300208

Kasperek, S. Design Principles. (2011). The Public Speaking Project. http://publicspeakingproject.org/psvirtualtext.html

Kosslyn, S. M. (2007). Clear and to the point: Eight psychological principles for compelling PowerPoint presentations. Oxford University Press.

Lacey, S., Stilla, R., & Sathian, K. (2012). Metaphorically Feeling: Comprehending Textural Metaphors Activates Sensory Cortex. Brain and Language. 120, 3. 416–421. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2011.12.016

Malamed, C. (2009). Visual language for designers: Principles for creating graphics that people understand. Rockport Publishers

Mantei, E. J. (2000). Using internet class notes and PowerPoint in the physical geology lecture. Journal of College Science Teaching, 29(5), 301–305. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/91984/.

Marsh, E. J., & Sink, H. E. (2010). Access to handouts of presentation slides during lecture: Consequences for learning. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24, 691–706. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1579.

Mayer, R. E. (2001).Multimedia learning.New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2002). Animation as an aid to multimedia learning.Educational Psychology Review, 14,87–99. https://doi.org/10.40-726X/02/0300-0087/0.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38,43–52. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3801

Medina, J. (2018). Brain rules. http://www.brainrules.net/vision

Miller, S. T., & James, R. C. (2011). The effect of animations within PowerPoint presentations on learning introductory astronomy. Astronomy Education Review, 10,1–13. https://doi.org/10.3847/AER2010041.

Moulton, S.T., Türkay, S. & Kosslyn, S.M. (2017). Does a presentation’s medium affect its message? PowerPoint, Prezi, and oral presentations. PLoS ONE 12(7): e0178774. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178774

Nelson-Wong, E., Eigsti, H., Hammerich, A., & Ellison, N. (2013). Influence of presentation handout completeness on student learning in a physical therapy curriculum. The Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13, 33–47. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1017035.pdf

Nouri, H., & Shahid, A. (2005). The effect of PowerPoint presentations on student learning and attitudes. Global Perspectives on Accounting Education, 2,53–73. (no doi).

Nowaczyk, R. H., Santos, L. T., & Patton, C. (1998). Student perception of multimedia in the undergraduate classroom. International Journal of Instructional Media, 25 (4), 367–382. (no doi).

Ogeyik, M. C. (2017). The effectiveness of PowerPoint presentation ad conventional lecture on pedagogical content knowledge attainment. Innovations in Education &Teaching International, 54, 503–510.https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1250663.

Presentation aids Design Principles. Lumen Learning. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/ivytech-comm101-master/chapter/chapter-13-design-principles/#return-footnote-1129-36

Ramgopal & Arte. (n.d.). Presentation Ppocess. https://www.presentation-process.com/powerpoint-slides.html

Reynolds, G. (2008). Presentation Zen: Simple ideas on presentation design and delivery. New Riders.

Schneider, S., Nebel, S, & Rey, G.D. (2015). Decorative pictures and emotional design in multimedia learning. Learning and Instruction 44, 65-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.03.002

Steinert, Y. & Snell, L.S. (2009). Interactive lecturing: Strategies for increasing participation in large group presentations. Medical Teacher. 21:37–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421599980011

Stenberg, G (2006). Conceptual and perceptual factors in the picture superiority effect. Europen Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 18. 813-847. https://doi.org/10.1080/09541440500412361

Swerdloff, M. (2016). Online learning, multimedia, and emotions. In S. Y. Tettegah & M. P. McCreery (Eds.), Emotions and technology: Communication of feelings for, with, and through digital media. Emotions, technology, and learning (p. 155–175). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800649-8.00009-2

Torgovnick May, K. (2012). How to give more persuasive presentations: A Q & A with Nancy Duarte. TED Blog. https://blog.ted.com/how-to-give-more-persuasive-presentations-a-qa-with-nancy-duarte/

Vogel, D. R., Dickson, G. W. & Lehman, J. A. (1986). Persuasion and the role of visual presentation support: The UM/3M Study.

Wecker, C. (2012). Slide presentation as speech suppressors: When and why learners miss oral information. Computers & Education, 59, 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.01.013.

Wilmoth, J., & Wybraniec, J. (1998). Profits and pitfalls: Thoughts on using a laptop computer and presentation software to teach introductory social statistics. Teaching Sociology, 26, 166–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/1318830

Worthington, D. L., & Levasseur, D. G. (2015). To provide or not to provide course PowerPoint slides? The impact of instructor-provided slides on student attendance and performance. Computer Education, 85,14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.02.002