Giving and Receiving Feedback: It is Harder Than You Think

- Your colleague asks you to listen to them practice their speech practice and give them feedback.

- Your teacher asks you to give feedback to another classmate about their speech.

- Your boss asks, “What did you think about my speech?”

In each case, the person is looking to you to provide feedback. In this chapter, you will learn about how to assess the feedback situation, how to offer constructive criticism, and how to graciously receive criticism. Let’s start with how to ask for feedback and listen graciously.

Receiving Feedback

When you ask for feedback from others, receive their feedback as a gift. Someone is taking their time and giving it to you; someone is putting themselves out there and saying things that might cause discomfort, but they are doing it for you. Individuals vary on how they receive feedback and how comfortable they are with being evaluated.

When receiving feedback, try doing the following:

- Sit in a non-defensive posture. It is tempting to cross your arms and to tense up all your muscles when receiving oral feedback. Keep your body open and loose. Staying open helps them to feel like you really want their suggestions and closed arms can equal a closed mind — keep an open body.

- Do not take feedback as a personal insult.

- If the feedback is verbal, write down the suggestions, even if you disagree with the suggestions. Respect the other person’s opinions by writing them down. It makes them feel like they have been heard and you appreciate the feedback they are giving. Writing the feedback down also helps you to not cross your arms defensively–see suggestion one– and it helps you remember the suggestions.

- Do not take it as a personal insult. Seriously!

- Avoid the temptation to defend yourself. “I did it this way because…” or, “I thought it would be best to…” You already know why you did things the way you did. Interrupting them to tell them the reasons you did what you did comes off as defensive and reduces the likelihood they will give you all the feedback they have to offer. You already know what you were thinking and by telling them you haven’t advanced your situation. Use this time to learn what they are thinking.

- Do not take it as a personal insult. Really, this is so important.

- Breathe. Most people feel stress when someone is giving them constructive criticism, breathe and relax so you can really listen.

- Do not take it personally. Do not take it personally. Do not take it personally. This cannot be emphasized enough! Since it is about your performance or your speech writing, it is hard not to feel criticism of your speech as a criticism of your person. Try to take criticism instead as someone caring enough about you to push you to grow.

After Every Speech, Do a Self-Evaluation

Allison Shapira of Global Speaking suggests you do a self-evaluation after each speech:

- What did I do well?

- What didn’t I do so well?

- What am I going to do differently next time?

Write these down and keep this on file for the next time you give a speech.

Constructive Criticism

There will be times when others look to you to read over their speech or listen to them practice and then give them constructive criticism. Constructive criticism is made up of two words: constructive–the building of something, and criticism–the giving of a critique. So constructive criticism is critiquing with the intention of building something. When we give others constructive criticism, our goal should be to help build them to be better speakers.

Give Them Help

Reagel and Reagle came up with a creative way to remember the goal of feedback, it should HELP:

Help the speaker improve

Encourage another speech

Lift self-esteem

Provide useful recommendations

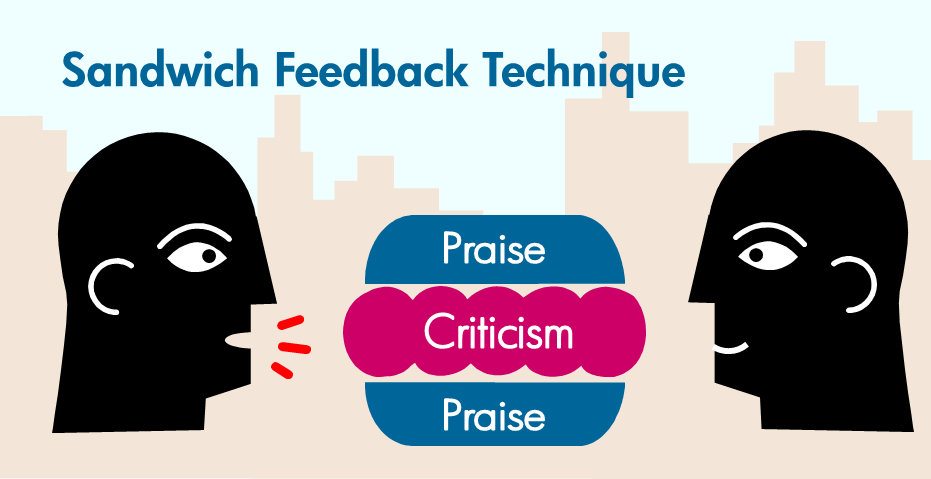

Give Them a Sandwich

One way to give constructive criticism is to use the sandwich method. Say something positive, give feedback about something they can work on to improve, and then say something positive. This way, the first and last words out of your mouth are positive.

Ask Questions

Ask honest questions that can help lead them to solutions or ask questions to soften the sound of negative feedback:

“What did you mean by…”

“Have you considered? ”

“Have you thought about…?”

“When you said… did you really mean?”

For example:

“Have you considered the impact of showing such a gruesome photo on your slide?”

“Have you considered starting with a quote? ”

“Have you thought about whether the people in the back will be able to see your poster?”

“Have you thought about using a microphone so everyone can hear you?”

Beyond the Sandwich: Data Points and Impact Statements

In her video, called “The Secret to giving Great Feedback”, LeeAnn Renninger refers to a 4 Step “Feedback Formula”.

Watch The secret to giving great feedback | The Way We Work, a TED series on YouTube (0 mins)

Video source: TED. (2020, Feb 10). The secret to giving great feedback – The Way We Work, a TED series. Leanne Renninger. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/wtl5UrrgU8c

In our college class, we will focus on steps 2 & 3.

Data points (or clear examples)

- Name specifically what you saw or heard, and leave out any words that aren’t objective. Avoid “blur words”, which are not specific and could mean different things to different people.

- Convert any blur words into actual data points or observations. For example, instead of saying, “You didn’t engage your audience”, be specific and say “Your introduction didn’t mention what the benefits are to the audience”

- Being specific is also important with positive feedback. Saying “I really liked your presentation” doesn’t offer the other person any clear ideas of what they should keep doing. Instead, try to name specifics: “You made it very easy to understand the process when you described [give the example],” or “The visuals you included showed that [give the example]”.

- Be as clear as you can, so the presenter knows to continue doing these things!

The Impact statement

- Don’t stop at just giving the “evidence” or describing your observations. Keep going – explain how what you saw and heard impacted you.

- You might say “I really liked how you added those stories, because it helped me grasp the concepts faster,” or “the way you opened your presentation surprised me and got my attention.

By providing data points as well as impact statements, your peer critiques will be clear, specific, and provide your classmate with something they can actually use to work on to improve!

Source: Except where otherwise noted, “Beyond the Sandwich: Data Points and Impact Statements” by Amanda Quibell is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Different People, Different Types of Feedback

It is no surprise that people give and receive feedback differently. One person might take a feedback statement and be grateful for the corrections while the next person might take it as a complete insult. Below, you’ll learn about some of the most common differences.

High and Low Self Monitors

Psychology researcher Mark Snyder identified people as being either high self-monitors or low self-monitors. High self-monitors typically try to fit in and play the role according to the context. They are about image, and they are motivated to fit in with their peers. They like to know what is expected, so they can adapt to the situation. Giving them useful feedback may mean pointing out how they can make changes in their message to meet the audience’s expectations. When giving feedback to high self-monitors, focus the feedback on how they can elevate their credibility in the eyes of the audience.

On the other hand, low self-monitors tend to be motivated to act based on their inner beliefs and values. They are motivated to be true to their sense of self and to above all– be genuine. When giving low self-monitors feedback, encourage them to be the best speaker they can be while being true to themselves. Focus on giving them feedback in a way that encourages them to harness their unique talents.

While you may not know exactly whether they are high or low self-monitor, you likely have some idea of what motivates them. The more you can tailor your feedback to them, the more likely it is they will hear what you are saying. If you are curious about your type, you can take the quiz. You can have the person giving you feedback take the quiz as well. This can be a helpful exercise to think about how you give and receive feedback.

Take the high and low self-monitor quiz to find out your type

Cultural Differences

When you know your sickness

You’re halfway cured.

French saying

In the book, The Culture Map, a Dutch businessman is quoted as saying. “It is all a lot of hogwash. All that positive feedback just strikes us in the face and not in the least bit motivating.” People from different cultural groups have different feedback norms. As our society grows increasingly diverse, it is important to learn not just how to give good feedback, but to give feedback that demonstrates an awareness of how different cultures give and receive feedback.

Erin Meyer does international training to help business professionals understand differences and similarities and how to bridge the gap:

Managers in different parts of the world are conditioned to give feedback in drastically different ways. The Chinese manager learns never to criticize a colleague openly or in front of others, while the Dutch managers learns always to be honest and to give the message straight. Americans are trained to wrap positive messages around negative ones, while the French are trained to criticize passionately and provide positive feedback sparingly. Having a clear understanding of these differences and strategies for navigating them is crucial for leaders of cross-cultural teams.

Erin Meyer, The Culture Map

Upgraders and Downgraders

Meyers identifies cultures as Upgraders and Downgraders. Upgraders use words or phrases to make negative feedback feel stronger. An upgrader might say, “this is absolutely inappropriate.” As you read this, see if you identify more as an upgrader or downgrader.

Upgraders say:

- Absolutely–“That was absolutely shameless.”

- Totally–“You totally missed the point.”

- Strongly–” I strongly suggest that you…”

By contrast, downgraders use words to soften the criticism. A downgrader might say, “We are not quite there yet” or “This is just my opinion, but…”

Downgraders say:

- “Kind of”

- “Sort of”

- “A little”

- “Maybe”

- “Slightly”

- “This is just my opinion.”

When giving and receiving feedback across cultures, it is helpful to be aware of these differences so you can “hear” what they are really saying. Take for example this statement as a Dutch person complains about how Americans give feedback.

The problem is that we cant’ tell when the feedback is supposed to register to us as excellent, ok, or really poor. For a Dutchman, the word “excellent” is saved for a rare occasion and “okay” is…well, neutral. But with the Americans, the grid is different. “Excellent” is used all the time, “Okay” seems to mean, “not okay.” “Good” is only a mild complement. And when the message was intended to be bad, you can pretty much assume that, if an American is speaking and the listner is Dutch, the real meaning of the message will be lost all together.

Erin Meyer, The Culture Map.

Nannette Ripmeester, Director of Expertise in Labour Mobility, illustrates these differences to her clients with a chart. This chart shows the differences between what the British say, what they mean, and what the Dutch understand. This is a condensed version of her list.

| What the British Say | What the British Mean | What the Dutch Understand |

|---|---|---|

| Very interesting | I don’t like it | They are impressed.

|

| Perhaps you would think about… I would suggest… |

This is an order. Do it or be prepared to justify yourself |

Think about this idea and do it if you like it.

|

| Please think about that some more | It’s a bad idea. Don’t do it. |

It’s a good idea, keep developing it.

|

| I would suggest | Do it as I want you to | An open suggestion

|

| An issue that worries me slightly | A great worry | A minor issue

|

| A few issues that need to be addressed | A whole lot needs to be changed | 2-3 issues need rewriting

|

Chances are as you read this list, you identified yourself in some of the statements and identified someone you know who is in the other list. Hopefully, this made you think about how personal style can be as different as cultural style. The big idea here is when you are giving and receiving feedback, it can be helpful to try to identify their communication style and adjust accordingly.

Politeness Strategies

As you already know, whenever you critique someone’s work, there is a potential to hurt their feelings. There are many factors that influence whether the feedback is helpful or hurtful. In communication, we use the term “face” to mean the sense of self a person projects. People can “take face” by creating a situation where someone looks bad to others or people can “lose face” by doing something that diminishes them in the eyes of others. Optimally, we want people to feel like they “gain-face” and feel encouraged. The way that you give feedback as well as the person’s natural tendencies will influence how “face” is affected.

When giving feedback, you should think about how your feedback takes or gives face. You also need to consider what is at stake for the other person. Is this a small speech assignment or is it a career-defining presentation? In addition, critiquing someone privately vs critiquing someone in front of their boss will have different “face” outcomes.

How much you are willing to “take face” from someone may depend on the importance of the feedback. You will likely want to provide more suggestions for someone who is doing a career speech to get their dream job vs that same person doing a college speech worth minimal points. You will likely be more invested in helping a friend polish a speech to make it just right as opposed to someone you barely know.

Finally, the other thing influencing feedback is the power difference between people. You will likely give feedback differently to your little sister than you would to your boss. The status of the individuals and how important power is to them will impact how “face” is taken and given. For example, a high-power country like China would consider an open critique of a teacher, boss, or elder a huge insult, whereas someone from a low-power country, would be less offended. In any situation, you will be negotiating power, context, and the need to save face.

Taking all these factors into account, Brown and Levinson created Politeness Theory as a way to explain the different ways we give feedback to save face.

Bald on Record: This type of feedback is very direct without concern for the person’s esteem face. This type of feedback is usually given if there is a small fix the speaker would feel strongly about.

Examples of bald on record feedback:

-

- “Be sure you bold the headings.”

- “Alphabetize the references.”

Positive Politeness: In this type of feedback, you would build up the face or esteem of the other person. You would make them feel good before you make any suggestions. (It looks a lot like the sandwich method, hunh?)

Examples of positive politeness feedback:

-

- “You are so organized; this one little fix and it will be perfect.”

- “I love the story you told, a few more details would really help me see the character.”

Negative Politeness: The name of this type of feedback is a little misleading. It doesn’t mean you are negative. It means you acknowledge that getting feedback may make them feel negative. You would say things that acknowledge their discomfort. You might minimize the criticism so it doesn’t make them feel bad or find other ways to soften the blow of criticism.

Examples of negative politeness feedback:

-

- “I know this critique might sound rough and I hope it helps, but I think you really need to work on the middle section.”

- “This is just me making suggestions, but I would be able to understand more if your slide has a heading.”

- I’m not an expert on this, but I think you might need to have a stronger thesis.”

- “I see what you are trying to do here, but I think some of your audience members might not get it.”

Off Record: When you give feedback that is off the record, you are hinting vaguely that they should make a change.

Examples of off the record feedback.

-

- “How many sources are we supposed to have?” (Instead of saying, “You need to have more research”)

- “I thought we were supposed to have slides with our speech, maybe I heard that wrong.”

- “Are other people in the class dressing up?”

Avoidance: Some people are afraid of giving feedback so they will avoid the situation altogether.

Try This

Avoid the three C’s

- Criticize

- Complain

- Condemn

Perform the three R’s

- Review

- Reward

- Recommend

From Westside Toastmasters

Giving Feedback During a Speech

When you are listening to someone speak, you are giving constant nonverbal feedback. Are you leaning forward listening intently or are you leaned back picking at your fingernails? The way you listen lets the speaker know that you value them and what they are saying. It can be reassuring to the speaker to have people who are in the audience smiling and nodding.

Try this little experiment: If you have a speaker who is average or boring, lean in and listen intently. Don’t be insincere and cheesy, but rather try to be an earnest listener. You will find that when the speaker notices you paying attention, they will usually become less monotone and more engaging. The speaker affects the audience, and the audience affects the speaker.

Asking for Feedback During Your Speech

Appoint someone to be your speech buddy who will give you signals and alert you during your speech, for example: to speak louder or to check your microphone. If you know that you tend to pace, lean on the podium, or say um’s, have them give you the signal.

Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak.

Courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen.

Winston Churchill

Former Prime Ministre of the United Kingdom

Key Takeaways

Remember This!

- Be open to the feedback of others, it can help you improve as a speaker.

- When giving feedback to others consider the context, their needs, the impact on their esteem, and their culture.

- Use the feedback sandwich as a model for giving constructive criticism.

Attribution & References

Except where otherwise noted, this chapter is adapted from “Giving and Receiving Feedback: It is Harder Than You Think” In Advanced Public Speaking by Lynn Meade, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

References

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1978). Universals in Language Usage: Politeness Phenomena. In E. Goody (Ed.), Questions and Politeness: Strategies in Social Interaction (pp. 56-310). Cambridge University Press.

Churchhill Central: Life and words of Sir Winston Churchill. https://www.churchillcentral.com/

Gonzales, M. (2017). How to get feedback on speeches. Global Public Speaking. https://www.globalpublicspeaking.com/get-feedback-speeches/

King, P. E., & Young, M. J. (2002). An information processing perspective on the efficacy of instructional feedback. American Communication Journal, 5 http://ac-journal.org/journal/vol5/iss2/articles/feedback.htm

King, P. E., Young, M. J., & Behnke, R. R. (2000). Public speaking performance improvement as a function of information processing in immediate and delayed feedback interventions. Communication Education, 49, 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520009379224

Mehra, A., Kilduff, M. & Brass, D.J. (2001). The social networks of high and low self-monitors Implications for workplace performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46 (1), 121-146. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667127

Meyer, E. (2014). The culture map: Breaking through the invisible boundaries of global business. Public Affairs. https://erinmeyer.com/books/the-culture-map/

Meyer, E. (2014). How to say “This is Crap” in different cultures. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2014/02/how-to-say-this-is-crap-in-different-cultures

Reagle, J.M. & Reagle, J.M. (2015). Reading the comments: Likers, haters, and manipulators at the bottom of the web. MIT Press. https://readingthecomments.mitpress.mit.edu/

Ripmeester, N. Rottier, B., & Bush, A. (2010). Separated by a common translation? How the Brits and the Dutch communicate. Pediatric Pulmonology. 46(4). 409-411. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.21380

Ripmeester, N. (2015). We all speak English, don’t we? https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/we-all-speak-english-dont-nannette-ripmeester/

Smith, C.D. & King, P.E. (2007). Student feedback sensitivity and the efficacy of feedback interventions in public speaking performance improvement. Communication Education 53(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/0363452042000265152

Snyder, M. (1974). Self-monitoring of expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 30 (4), 526-537. http://www.communicationcache.com/uploads/1/0/8/8/10887248/self-monitoring_of_expressive_behavior.pdf

Toastmasters International. (2017). Giving effective feedback. https://www.toastmasters.org/resources/giving-effective-feedback