Persuasive Speechmaking: Motivating Change

Audience Needs are Key

According to Professor Clay Warren, a common mistake you might make is focusing on what you want to say rather than considering what the audience needs to hear.

Before delivering a persuasive speech, take the time to gather information about the audience and the event. Envision the faces of the audience and understand who they are and what motivates them to listen. Then, think about how their message can improve the lives of the audience in some way.

Once you have a clear mental picture of the audience, you can begin to write the speech.

The Audience Needs to “See” to be Persuaded

If you are persuading an audience to buy a product, they need to visualize how it works and how it fits into their life. If you are persuading an audience to make a social change, they need to visualize how the world will be better because of this change. If you are persuading an audience to donate to an organization, you need to help the audience visualize the impact of their donation.

Visualization can be achieved by literally showing visuals, by demonstrating the product, or by telling a story.

Oftentimes a story will help awaken emotions in an audience. This is known as pathos. Pathos is the passion of the speaker and the types of things that the speaker talks about. Warren reminds us “facts go through your brain like water through a sieve. But a story creates an emotional connection. If you get the emotion, you will remember. It is harder to attach an emotion to a number.”

The Audience Needs to Be Given the Facts in a Way that They Can Understand, Relate, and Remember

Yes, you want to identify with an audience and help them feel something, but you also need facts in your speech. You need to do the research and you need to present the arguments. Keep in mind — facts alone are rarely persuasive. It is the way you present those facts that makes them persuasive. When giving your numbers, pair them with a story. When giving statistics, helped the audience to visualize them.

Make sure you chose to talk about facts that match the audience. For some, the review of a social media influencer is more convincing than the reviews from a publication. For an academic audience, the names of the researchers and the names of the journals they publish in will garner attention, but for other audiences, the title of the person as “cardiologist at a top research institute” would be more persuasive.

The Audience Needs to Trust You

Credibility is key to the success or failure of a presenter. The whole speech rests on credibility, if they don’t trust you, they won’t listen. You build your credibility by how you are dressed, how you are introduced, how you tell the audience why you are competent in this area helps the audience listen. In my story, our credibility came from the name of the big company that used our parts.

Your credibility helps create trust and trust is essential to persuasion.

Ethos: Credibility

Ethos (credibility) is all about your character, your intentions, your good judgment, as well as your respect for yourself, your speech, and your audience. Aristotle said there are three components of ethos and all three should be employed.

- Phronesis (froh-nee-sis) practical wisdom. Prudence. It implies good judgment and excellence of character and habits.

” To do the right thing in the right place, at the right time, in the right way.” -Carr - Arete (ah-reh-‘tay) is the moral virtue of your argument. It refers to excellence of any kind but when applied to speech it means to persuade in a morally virtuous way.

- Eunoia (you-noh-iea) is the goodwill you establish. It is what happens when a speaker considers the audience and cultivates a relationship of trust with them.

Watch How can you change someone’s mind? (hint: facts aren’t always enough) – Hugo Mercier (3 mins) on YouTubefor the connection between what we have just discussed on credibility and audience needs.

Video source: TED-Ed. (2018, July 26). How can you change someone’s mind? (hint: facts aren’t always enough) – Hugo Mercier [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/58jHhNzUHm4

Make it Do-Able

Persuasion needs to be doable. Be specific with what you want the audience to do. Are you wanting them to consider an opposing viewpoint? Are you wanting them to donate blood? Are you wanting them to give to a charity? Are you wanting them to see the value of a liberal arts education? Are you wanting them to buy your product? Tell them specifically what you want.

To make your persuasion effective, you need to make it achievable by being specific about the desired action from your audience. This could be encouraging them to consider an opposing viewpoint, donating blood, giving to a charity, seeing the value of a liberal arts education, or buying your product.

Giving realistic goals is another way to make it achievable. For example, a health and fitness program aimed at promoting healthy practices would be more successful if it encouraged participants to do chair yoga at their desk or add one more serving of fruit or vegetable to their diet, rather than asking them to run five miles a day. Similarly, in sales or donor engagement, it’s important to set realistic goals based on the audience’s financial means or stock only the most popular items to test customer satisfaction.

Lastly, telling the audience how to accomplish what you’ve asked for will make it easy for them to comply. For example, if you are promoting a tourist attraction, you could show them on a map where it’s located, share pictures of the experience, and tell them what to pack. By providing visual aids, you can help your audience to better visualize themselves doing it and increase their likelihood of following through with your request.

Overcome Objections

When you’re trying to sell something or persuade someone, it’s important to be prepared for objections. In a one-on-one sales pitch, you might ask, “Is there anything that’s holding you back?” When you’re giving a persuasive presentation, you can do the same thing, but in a more subtle way.

Think of getting a flu shot – you’re given a small dose of the flu to build immunity for the future. In the same way, giving someone a small dose of an opposing argument can help them prepare for future persuasion attempts. This is called inoculation theory.

You can do this by forewarning your audience of what they might hear from the other side. For example, if you’re trying to persuade someone to try chiropractic treatment for headaches, you might say, “You may hear that chiropractors are just trying to get your money, but my own experience has been…” By warning them and helping them think about how they might argue for their side, you’re building their immunity.

Another way to overcome objections is by preemptively addressing counterarguments. This is called refutational preemption. Think about what objections your audience might have and address them in your presentation. For instance, if you’re trying to sell aftermarket diesel engine parts, you might imagine they’ll object because your product isn’t a name-brand. In response, you could say, “Let me tell you why the quality of our product is equal to the competition” and show them data and statistics.

When you’re inoculating your audience, make sure you don’t make the other side’s argument too strong, or they might end up agreeing with them. Also, don’t misrepresent the other side’s position, as that would be unethical and could hurt your credibility.

When working on a persuasive presentation ask several people, “Why might someone object to this?” or “Why might someone not want to try this?” When they answer. Resist the temptation to justify. Don’t be defensive, just listen and write down the things they say. Go back to your speech and see how you might preemptively deal with those objections in your presentation.

Look for Agreement

When someone says, “No.” Their whole body begins to disagree. They may lock their jaw, squint their eyes, or cross their arms. Keeping your speech positive and seeking agreement can draw an audience into your topic. Dale Carnegie in his famous book, How to Win Friends and Influence People suggested getting the audience to say, “Yes” multiple times. Even better if they nod yes as well. “Can we agree tuition is too high–yes. Can we agree it is hard to eat healthy as a college student–yes. Can we all agree…fill in the blank…yes?”

Begin with the End in Mind

When thinking about your persuasion speech, ask yourself how you will measure success? Success in speech class should always be more than the grade you earned. Earnestly try to persuade your classmates of something that will make their lives better.

For example, a student group successfully convinced the city to add a traffic signal in front of their college, potentially saving lives. Another student recommended a weekend trip to Quebec City and several classmates followed through, thanking them for the recommendation. Measurable success can also come from changing attitudes, even if it’s not immediately tangible. Sometimes success means simply getting the word out or planting a seed that will eventually persuade others. Make sure to write down your desired outcome and what you hope to achieve with your speech.

Always begin with the end in mind.

Persuasion to Change Your Behaviour

Watch Less stuff, more happiness (6 mins) on TED

I’m not saying that we all need to live in 420 sq. ft. But consider the benefits of an edited life. Go from 3,000 to 2,000, from 1,500 to 1,000. Most of us, maybe all of us, are here pretty happily for a bunch of days with a couple of bags, maybe a small space, a hotel room. So when you go home and you walk through your front door, take a second and ask yourselves, “Could I do with a little life editing? Would that give me a little more freedom? Maybe a little more time?”

NOTICE

He tells you what he wants you to do, and he makes it do-able. Notice how he slows down and changes his voice and the ending as he delivers his last words–“Good stuff.”

Source: Hill, G. (2011). Less stuff, more happiness [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/graham_hill_less_stuff_more_happiness

Culture Makes a Difference

There are a lot of demographic differences that can influence how a person is persuaded, and an important one of those is culture. I want to focus on the biggest three cultural differences that can influence how you approach a persuasive speech.

Individualism vs Collectivism

- Individualistic cultures stress the value of “I.” People in individualist cultures typically value independence and uniqueness and are socialized to see themselves as separate and distant.

- Collectivistic cultures stress the value of “we.” People in collectivistic cultures value group membership. They tend to work towards the good of the group and are more compliant with authority.

- A speech that tells the audience how to be independent or how to stand out above the crowd would appeal more to an individualistic audience where a speech that tells the audience how they can fit in and be part of the group would appeal more to a collectivistic culture.

- One study showed the difference in detergent ads. “Cleans with a softness that you will love” was preferred by individualistic societies vs “Cleans with a softness your family will love” was preferred by collectivistic societies.

High vs Low Context

-

- Low context cultures tend to be direct and linear. There is an emphasis on facts as the most important.

- High context cultures tend to be indirect. Because of the indirectness, it may be harder to “read” the situation unless you have taken time to get to know the individual.

- Doctor recommended would appeal more to high context individuals where a focus on the features and advantages of the product would be more persuasive to low context individuals.

- A speech that is very specific and direct would appeal to a low context culture where a speech that implies or “hints” would appeal more to a high context culture.

Persuasive Speech Pattern: Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

There are many patterns you can use as you create your speech. We’ll concentrate on Monroe’s Motivated Sequence.

This model, designed by Alan Monroe, was originally designed for policy speeches but has been expanded to other types. Sales presenters take note, this one may be for you. Participants in one study appreciated this format because of how organized it makes presentations.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

Attention:

Begin by capturing the audience’s attention with a grabbing statement, a preview, and a credibility statement. For instance, if the speech is about the importance of healthy eating, the speaker could start with a startling fact such as, “Did you know that poor nutrition contributes to over 11 million deaths globally each year? As a certified nutritionist with 10 years of experience, I’m here today to shed light on the importance of making healthier food choices.”

Need:

This step aims to create a sense of urgency or establish a need for change. Present evidence or examples that highlight the need. Continuing with the topic of healthy eating, the speaker could provide statistics on the rising rates of obesity and chronic diseases caused by poor diets, emphasizing the negative impact on individuals’ health and quality of life.

Satisfaction:

In this step, you satisfy the need with a plan to address it Present concrete steps or strategies that can satisfy the need established in the previous step. In the context of healthy eating, the speaker could discuss the benefits of a balanced diet and propose practical tips for incorporating more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains into daily meals.

Visualization:

Help the audience visualize the benefits of implementing the proposed solution. Paint a vivid picture of the positive outcomes that can be achieved. Using the healthy eating example, the speaker might describe how individuals who adopt healthier eating habits experience increased energy, improved mood, and reduced risk of chronic diseases. Additionally, they could share success stories of individuals who have made positive changes to their diets and reaped the rewards.

Action:

Tell the audience exactly what you want them to do. This step includes reviewing the main points, providing a specific call to action, and delivering a closing statement. In the case of promoting healthy eating, the speaker could summarize the key benefits of adopting a balanced diet, urge the audience to start making small changes immediately, such as replacing sugary drinks with water, and conclude with an empowering statement like, “Together, let’s take charge of our health and make nutritious choices for a better future.”

Applying Monroe’s Motivated Sequence to persuade an audience

Watch Overworking’s impact on life: The importance of balance (6 mins) on YouTube

In this presentation created for Dynamic Presentations at Georgian College, Joshua Morgan uses Monroe’s motivated sequence to persuade his audience to try to establish a healthy work-life balance. He starts by grabbing his listener’s attention and highlighting the negative consequences of overworking; then, he moves on to establish the need for a better way of working. Next, he presents the solution – a work-life balance – and emphasizes its benefits. Finally, he provides some strategies for his audience to achieve a work-life balance and emphasizes the importance of self-care. His message is that we can change our own lives and those of others by not following society’s norms of overworking.

Source: Morgan, J. (2023). Overworking’s impact on life: The importance of balance [Video]. https://youtu.be/pyYtSWkVmSc

Words are powerful. When you are given the privilege of standing before a group of people, they have given you the gift of time. You owe it to them to give them something worthwhile. You now have some powerful persuasive tools, use them wisely, apply them ethically.

The Science of Persuasion

Don’t raise your voice, improve your argument.

―

Understanding persuasive strategies, like the Elaboration Likelihood model and Judgement Heuristics can help you develop your approach to your next persuasive speech. By applying these principles effectively, you can strategically approach your presentation to address the audience’s needs.

Elaboration Likelihood Model

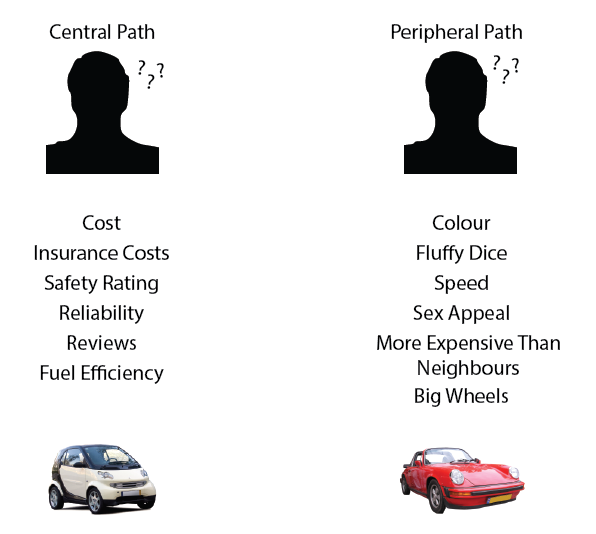

The Elaboration Likelihood Model, developed by Petty and Cacioppo, explains how persuasion works in different situations. It suggests that there are two routes to persuasion. When we think carefully about our decisions, considering personal involvement and relevance, we are taking the central route. On the other hand, when we don’t think deeply due to various factors like the situation, mood, or the insignificance of the decision, we are taking the peripheral route. The peripheral route involves making decisions based on factors other than deep thought, such as authority.

Understanding these different routes of persuasion can help you design effective persuasive arguments for your speech. It’s important to decide whether you want to engage in thoughtful persuasion or peripheral persuasion.

Elaboration Likelihood Model–What’s the Big Idea?

- If you want your persuasion to be long-lasting, persuade them via the central route. Offer facts, data, and solid information

- If you want a quick persuasion where they don’t put much thought into it or if your audience is not very knowledgeable, tired, or unmotivated, persuade them by the peripheral route.

Judgmental Heuristics

In Elaboration Likelihood Model, we find that people are persuaded in one of two ways– because they are thinking about it–the central route–or they are not thinking about it–peripheral.

Judgmental heuristics, as researched by Robert Cialdini, refer to mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that people use to make quick judgments or decisions. These heuristics are cognitive strategies that help simplify complex information processing and enable individuals to make rapid assessments or choices based on limited information.

Cialdini identified several specific judgmental heuristics, including:

Authority

People tend to rely on the expertise, status, or credibility of an authority figure or source to make judgments or decisions. This heuristic leads individuals to assume that information or recommendations from authoritative sources are more valid or accurate.

Liking

People are persuaded by those they like–that is obvious. What is not so obvious are the ways that liking can be enhanced–similarity, compliments, and concern. People are more likely to like people who dress like them. If you are giving a speech to a group in ties, you should dress formally. If the group is more of a T-shirt and khakis type, you shouldn’t dress as formally. People like people who are similar. By researching your audience well, you can find ways to look for common ground.

Another way to enhance liking is with a sincere compliment. I’m not talking about a cheesy, overly flattering type. I am also not suggesting that you lie. I am saying that you can find something to like about them and let them know. In her TED Talk, Lizzie Valasquez had a very enthusiastic front row and she looked down and said, “You guys are like the best little section right here.” Finally, people like those who are passionately concerned about an issue. As a speaker, don’t aim to be perfect, aim to be passionate.

Commitment Consistency

Commitment/consistency has to do with finding something that people are already demonstrating a commitment to and then encouraging them to act in a consistent manner. People tend to align their behaviors, beliefs, and choices with their past commitments or previous actions. If you see someone carrying a water bottle, you can say, “I see you are committed to health. I notice you take that bottle with you to all your classes. I would like you to think about one more thing that can influence your health.” In this example, you find something that a person is committed to and you encourage them to be consistent.

When you research your audience, find things that they care about and touch on those as you encourage them to be consistent. When I spoke to community groups as a fundraiser, I would look up their mission and it often involved something about helping people so I might say, “I see from your mission that you are community-minded. I would like to share with you one more way that you can carry your mission into this community by helping.”

Social Proof

People look to other people to know how to act. This heuristic is based on the assumption that if many others are doing something, it must be the correct or appropriate course of action.

If you are doing a persuasive speech on a product, you can ethically persuade using social proof by showing how many stars a product has or you could read a poll about how many people support a measure. You can also interview those who are similar to your audience and then report back your findings. Talking about what Instagram and YouTube influencers believe can be powerful if it is someone the audience cares about.

Each of these judgmental heuristics carries with it the danger of abuse, so it is important to be ethical in your use of persuasion. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention to you that when it comes to social proof, it can become a bandwagon fallacy. Take for example fad diets. Just because they are popular, doesn’t mean they are healthy. Just because everyone thinks it is true, that doesn’t mean that it is true. When persuading using social proof, we want to ethically show why others like something and avoid the bandwagon fallacy which assumes that just because a lot of people like something that it must be good.

Scarcity

People hate to miss out on things which is why scarcity as a persuasive tool is so powerful. Scarcity can happen because there is not very much of something, (limited numbers) or there is not very long to get it, (limited time) or the information is restricted (limited information). As a speaker, you can encourage your audience to act immediately because the deadline is coming soon or to buy a product because they are likely to sell out.

People hate to have their options limited. “Don’t tell me I can’t have it because then I want it.” Researchers talk about this in terms of psychological reactance. Psychological reactance is a heightened motivational state in reaction to having our freedoms restricted. This, in part, explains why ammunition sales skyrockets under the threat of gun control measures and why teenagers fall even more madly in love when parents forbid them to date. Leveraging psychological reactance ethically can be tricky, but it can de be done. “There are just 20 more days until the election to research your candidate” or “concert tickets usually sell out the first few hours so if you want to go you have to be ready.” These are honest statements that can encourage the audience to act.

Reciprocity

We feel obligated to repay others when they do us a favour or give us a gift. We’re more likely to do something for someone who has previously done something for us.

Jane McGonigal in her TED Talk, The Game that Can Give You 10 Extra Years of Life, said: So, here’s my special mission for this talk: I’m going to try to increase the life span of every single person in this room by seven and a half minutes. Literally, you will live seven and a half minutes longer than you would have otherwise, just because you watched this talk.” She is promising to give us something in exchange for our time so we feel the pressure to listen.

Unity

People want to feel a sense of unity with a group. This group can be everything from their favorite sports team to whether they or dog or cat lovers. Finding ways to help the audience feel like a special group or like they are part of something, can be important to persuasion. “Join the club,” “be one of us,” “as Razorback’s we all feel…” are examples of how that is used. Another way to activate the principle of unity is to use insider language (if you are part of the group if not, it comes off as sucking up or cheesy).

Judgmental Heuristics–What’s the Big Idea?

- People take shortcuts when making decisions: authority, liking, commitment and consistency, social proof, scarcity, reciprocation, unity.

- It is important to be ethical when you use shortcuts.

You cannot reason people out of a position

that they did not reason themselves into.

― Bad Science

Key Takeaways

Remember This!

- Audience needs are key.

- The audience needs to “see” to be persuaded.

- Credibility is essential.

- Persuasion needs to be doable.

- Look for agreement.

- Overcoming objections.

- Consider how you will measure success.

- Consider cultural differences.

- The Elaboration Likelihood Model assumes that people are persuaded via a thinking (central) or nonthinking (peripheral) route.

- Judgmental Heuristics is using shortcuts to decide. These shortcuts are authority, commitment/consistency, unity, reciprocity, liking, scarcity, social proof.

Attribution & References

The from this chapter is adapted from “Persuasive Speechmaking: Pitching Your Idea and Making it Stick” and “The Science of Persuasion: A Little Theory Goes a Long Way” In Advanced Public Speaking by Lynn Meade, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

References

Allen, M. (2017). The sage encyclopedia of communication research methods (Vols. 1-4). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc doi: 10.4135/9781483381411

Aristotle. (1999). Nicomachean Ethics trans. Terence Irwin. Hackett.

Banas, J. A., & Rains, S. A. (2010). A meta-analysis of research on inoculation theory. Communication Monographs, 77(3), 281–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751003758193

Boundless (n.d). Types of Persuasive Speeches. Boundless Communications. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-communications/chapter/types-of-persuasive-speeches/

Carnegie, D. (2009). How to win friends and influence people. Simon and Schuster.

Cialdini, R.B. (2016). Pre-suasion: A revolutionary way to influence and persuade. Simon and Schuster.

Cialdini, R.B. (2009). Influence science and practice. Pearson.

Clapp, C. (2019). How to persuade others. Learn about your listeners, tailor your speech to their needs, and brush up on your Aristotle. Toastmaster’s International. https://www.toastmasters.org/magazine/magazine-issues/2019/apr/how-to-persuade-others

Compton, J., Jackson, B., & Dimmock, J. A. (2016). Persuading others to avoid persuasion: Inoculation theory and resistant health attitudes. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00122

Gass, R.H. & Seiter, J.S. (2014). Persuasion, social influence, and compliance gaining. Pearson

Goldwater, B. Bad science quote. Goodreads.

Hogan, K. (1996). The psychology of persuasion: how to persuade others to your way of thinking. Pelican.

Koo, M. & Shavitt, S. (2010). Cross-cultural psychology of consumer behavior. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444316568.wiem03041

Martin, S. (2010). Being persuasive across cultural divides. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2010/12/being-persuasive-across-cultur

Micciche, T., Pryor, B., & Butler, J. (2000). A test of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence for its effects on ratings of message organization and attitude change. Psychological Reports. 86(3 Pt 2), 1135–1138. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2000.86.3c.1135

McGuire W. J. (1961). The effectiveness of supportive and refutational defenses in immunizing and restoring beliefs against persuasion. Sociometry 24, 184–197. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786067

McGuire, W. J. (1961). Resistance to persuasion conferred by active and passive prior refutation of the same and alternative counterarguments. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63(2), 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048344

O’Keefe, D. (2008). The international encyclopedia of communication. John Wiley and Sons.

Petty, R.E. & Cacioppo, J.T. (1984). Source factors and the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 668-672.

Tutu, D. (2004). Address at the Nelson Mandela Foundation in Houghton, Johannesburg, South Africa. Goodreads.

Wilfred, C. (2005). What is the philosophy of education? The Routledge Falmer Reader in the Philosophy of Education. Routledge.

Wright, G. & Ferenczi, N. (2018). Cross-cultural dimensions impacting persuasion and influence in security contexts. Center for Research and Evidence on Security Threats. https://crestresearch.ac.uk/comment/cross-cultural-dimensions-impacting-persuasion-and-influence-in-security-contexts/