14 Inked Ancients: Perceptions of Tattooing in Ancient Greece

Basil Tabes

The art of tattooing has been practiced for thousands of years, with examples going back to the Neolithic period, such as the famous Ötzi the Iceman. Throughout the world, the creation of tattoos has been used in a wide variety of contexts. The significance of tattoos has ranged from sacred rites, medicinal operations, rites of passages, marks of punishment, and purely aesthetic purposes. While tattooing has a long and varied history worldwide, it is almost non-existent in the ancient Greek world. As we will see, this is due to notions of Greek identity that contrast Greeks with the “barbarian”.

Tattooing Practices in the Ancient World

The method by which tattoos were created in the ancient world is still in use to this day. Commonly known as “stick and poke” in English, this technique was used for the vast majority of tattoos done before the invention of modern tattooing machines. The process is simple, with the artist using a sharp needle to insert small amounts of pigment under the skin. Mummified remains of Scythian nobles display the intricate details that artists were able to achieve using this technique (Fig. 14.1).

The earliest tattooing instruments were made of sharpened bone, with soot, ash, charcoal, and ochre used as the “ink”. By the Classical period of Greece, the materials used for needles included bronze, iron, and even gold. It has been proposed that another method, known as “incision tattooing”, was used to a lesser extent, in particular for geometric patterns. This method consists of scoring lines into the skin with a sharp blade, usually made of flint or other sharp stones, then rubbing pigment into the wound.

The Greeks and the “Tattooers”

While the Greeks did not practice tattooing themselves, they were frequently in contact with cultures that did. Among the most notable are the Thracians, Persians, Scythians, and Egyptians. As discussed throughout this book, the Greeks utilized dress as a means of differentiating themselves from non-Greeks, with tattoos explicitly characterized as non-Greek.

This identification was so prevalent that tattoos were used in artistic media as a way to make a character identifiable as a foreigner. An example of an Amazon (Fig. 14.2), a mythical woman warrior, dressed in Persian-influenced dress, shows tattooing on her arms and neck to further suggest her ethnicity. This dichotomy is best displayed by the inscription on a 5th century grave stele (now in the Getty Museum) commemorating a deceased hoplite from the city of Megara: “I, Pollis, dear son of Asopichos, speak: Not being a coward, I, for my part, perished at the hands of the tattooers.” The mention of “tattooers” is almost certainly a reference to the Persians, who utilized tattooing as a means of punishment in the Greco-Persian Wars (Hdt. 7.233), or the Thracians, who are the most commonly depicted tattooed peoples in Greek art.

While all instances of tattoos in the literature and art of ancient Greece depict foreigners, Thracians are by far the culture most closely associated with tattoos. Herodotus says, “Among the rest of the Thracians… To be tattooed is a sign of noble birth, while to bear no such marks is for the baser sort” (Hdt. 5.6). The Thracians were regarded by the Greeks as a warlike and hedonistic culture, with heavy associations with Dionysian cults. Another negative interpretation of tattoos in Greek literature closely associates tattoos with enslavement. The associations of enslaved peoples with tattoos may stem from the fact that a significant portion of the enslaved population in Greece was Thracian.

The most commonly depicted tattoos are geometric, largely consisting of linear patterns, dots, and chevrons. Depictions with greater detail have shown figural tattoos on the arms and lower limbs, with deer, serpents, and suns being the most common (Fig. 14.3; see also Fig. 6.3 in chapter 6). These figure types are closely associated with Thracian cult practices and may be a direct representation of real Thracian tattoos. As nearly every Greek depiction of tattoos are representations of Thracians, the styles of non-Thracian cultures remain unclear.

Tattoos and Women

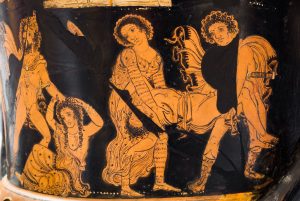

Despite the claim of Herodotus that suggests tattooing was practiced by noble Thracians of any gender, Greek art only depicts tattoos on Thracian women. When Thracian men and women are depicted together, the men have clear skin while the women are tattooed across their entire bodies (Fig. 14.4).

There is a recurring belief among Greek authors that the tattoos of Thracian women originated as a punishment. Athenaeus recounts a story from Clearchus of Soli about Thracian women captured and then tattooed by Scythians, who wanted to punish them. Upon release, the Thracian women are said to have tattooed the entirety of their bodies, transforming the marks from punitive to decorative (Ath. 12.27). Depictions of tattoos in Greek art almost exclusively appear in the context of the death of Orpheus. In the myth, the Thracian singer/prophet Orpheus is torn apart by a mob of frenzied Thracian women wielding spears and swords, commonly identified as maenads (followers of Dionysus). Some versions of this story state that this is the origin of tattooing in Thrace, with tattoos being variously described as a punishment for the women’s crime or as a symbol of mourning created by the women themselves (although the women are frequently depicted as already having tattoos when attacking Orpheus). The close relation between Thracian women and tattoos likely relates to the fact that Thracian women were viewed as antithetical to the ideal Greek woman. While Greek women were expected to be reserved, modest, and concealed (whether indoors or by a himation), Thracian women are portrayed as wild, indulgent, and exposed (see further chapter 6).

Tattooing Greeks?

While it is clear that the Greeks were opposed to tattooing themselves, it is unclear whether or not they tattooed others. Numerous scholars claim that the Greeks utilized punitive tattooing, the practice in which enslaved people and captives were permanently marked. There is little evidence, however, to support this practice in the classical Greek period, since the earliest references that concretely identify punitive tattooing come from the Roman period, when the tattooing of enslaved people was common. Plutarch, for example, recounts a story where Samians had marked captive Athenians with an owl, a symbol of Athens, and Athenians marked Samians with a boar-headed ship as a means to identify them during the Samian War (Plut. Per. 26). But his claim is not corroborated in contemporary accounts and so may not be historically accurate. It is possible that punitive tattooing was a recurring trope in comedic plays during the classical period, appearing throughout the works of Aristophanes. In his play, Birds, for example, a character references the “runaway slave, whom you ‘marked'” (Aristoph. Birds 752). Whether the playwright is referring to tattooing or branding (a different method of permanently marking an animal or person using a heated metal instrument) is heavily debated. This debate is due to the ambiguity of the terminology (stigma or “mark”), as well as a lack of evidence for Greek-produced tattoos in comparison with branding.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Dinter, M. T., and A. Khoo. 2019. “‘If Skin Were Parchment…’: Tattoos in Antiquity.” In Tattoo Histories: Transcultural Perspectives on the Narratives, Practices, and Representations of Tattooing, edited by S. T. Kloß, 85–102. New York: Routledge.

Jones, C. P. 1987. “Stigma: Tattooing and Branding in Graeco-Roman Antiquity.” The Journal of Roman Studies 77: 139–55.

Kamen, D. 2010. “A Corpus of Inscriptions: Representing Slave Marks in Antiquity.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 55: 95–110.

Rees, O. 2019. “Incompatible Inking Ideologies in the Ancient Greek World.” In Tattoo Histories: Transcultural Perspectives on the Narratives, Practices, and Representations of Tattooing, edited by S. T. Kloß, 277–94. New York: Routledge.

Tsiafakis, D. 2000. “The Allure and Repulsion of Thracians in the Art of Classical Athens.” In Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, edited by B. Cohen, 365–89. Leiden: Brill.

Zidarov, P. N. 2017. “The Antiquity of Tattooing in Southeastern Europe.” In Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing, edited by L. Krutak and A. Deter-Wolf, 137–49. University of Washington Press.