13 Shades of Ancient Greece: Skin Tone and Identity in the Greek World

Sam Peterson

The skin, or epidermis, is the largest organ in your body. It comes in thousands of shades based on the melanin present in your skin cells and protects you from the outside world. Unlike many of the adornments in other chapters, skin is something you are born with, and it remains with you always, nor can it be taken off. A person’s skin tone can even give clues about their geographic homeland, ancestry, and occupation.

Gender, Status, and Skin Tone

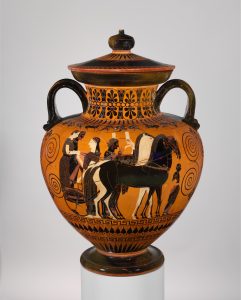

Skin tone in Ancient Greece was heavily associated with status and gender, with the ideals being tanned, brown-skinned men and pale, white-skinned women. This chromatic dichotomy existed in Greek art as far back as the Bronze Age (c. 3500-1050 BCE) with the Minoan (c. 3500-1100 BCE) and Mycenaean (c. 1750-1050 BCE) cultures, and was likely influenced by Egyptian art. The black-figure amphora on the left demonstrates this chromatic difference, showing two men painted in black while the two women stand out with their pale, white skin (Fig. 13.1). Paleness and its association with femininity continued into the archaic and classical periods. In Homeric epic poetry (c. 750 BCE), whiteness, Bridget Thomas argues, became synonymous with chastity, moderation, and other womanly virtues. Only when Hera, the goddess of marriage and Queen of the Olympians, is obedient toward her husband, Zeus, or sympathetic towards the Greeks, Homer refers to her with the epithet leukolenos, “white-armed” (Hom. Il. 1.193-6); in contrast, when she is disobedient or defiant, she is referred to as bopis potina or “ox-eyed” instead, emphasizing her eyes and thus immodesty (Hom. Il.1.568-9).

The difference in representation likely had to do with the fact that women were generally paler than men because of their roles in the domestic sphere. Women typically spent more time indoors (this was especially true for wealthy women), whereas men typically spent their time outdoors. In his treatise Oikonomikos (Economics), Xenophon, the classical Athenian philosopher, states that an ideal woman’s domain is inside, maintaining the household, and a man’s is outside (Xen. Oik. 7.20-32). The ideal skin tone for a man was a healthy and tanned complexion that represented his work in the fields or his presence in the public realm at the agora, assembly, and in the law courts (all open-air). The ideal man was neither too pale, like a woman, nor too dark, like an enslaved person who worked long hours in the sun.

Altering and Maintaining One’s Skin Tone

Cosmetics such as miltos, a product made from red lead, and andreikelon, a masculine flesh-toned eye makeup, could be used to tan the skin artificially, but these products were highly controversial. For men, being outdoors was seen as a necessity and a public good, and men whose jobs required them to be indoors were critiqued for this (Xen. Oik. 4.2). Meanwhile, women with darker complexions would use psimythion, a type of makeup made of chalk or white lead carbonate, to lighten their skin tones and provide protection from the sun. Psmiythion came in small tablets or cakes and was often stored in small ceramic containers such as a pyxis. However, it is important to note that while white lead provided some sun protection, long-term exposure would cause lead poisoning. For more on cosmetics, see chapter 12. Other ways in which women could protect their skin were through strategically draping their himations (see chapter 4), wearing head-coverings, and using parasols. Rouges were used to make a woman’s complexion appear more youthful and rosy-cheeked. The two primary varieties were enchousa, a product made of alkanets, a plant whose roots produce a red dye, and phukos, concocted from either a lichen called orchella weed or red ochre, a type of iron oxide high in the mineral hematite, which was used for its red pigment. Many women across socioeconomic lines made ample use of cosmetics, as made evident through their frequent inclusion in the grave goods of female burials.

Non-Greeks in a Greek Context: Race, Culture, and Identity

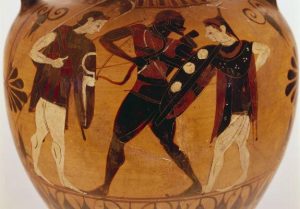

While racial differences, particularly skin tone, were recognized, cultural differences were far more significant. The Greeks designated anyone culturally different from them as a barbarian, regardless of their skin colour. In vase paintings, foreigners and non-Greeks are most often identified through their clothing; their foreignness is not necessarily evident through their skin tone, but by the fact that they are not wearing Greek clothing. The exception to this is artistic representations of Aithiopians, a semi-mythical people whose name means “burnt-faced,” referencing their dark complexion. The name was derived from the compound of the words aithō (“I burn”) and ops (“face”). The Aithiopians are referred to by a number of Greek writers, such as Homer (Hom. Il. 1.423) and Herodotus (Hdt. 3.17-26), as being from the edge of the Greek world, an area roughly corresponding to North Sudan. Their black skin is depicted in vase paintings, coupled with facial features associated with the region. The central dark-skinned figure in Fig. 13.2 is believed to be Memnon, King of the Aithiopians, who fought in the Trojan War. He is flanked by two Amazonian women who can be distinguished from their Greek counterparts by their clothing and the setting.

Greek literature suggests that while the difference in racial skin tones was a factor, cultural differences are the determining factor for Greekness as opposed to racial markers like skin tone, as in the case of the Danaids, the fifty daughters of Danaus, in Aeschylus’ Supplicant Women (Aesc. Supp. 1.1-10). In this play, Danaus and his daughters flee from their homeland of Egypt to seek the protection of their distant relative, King Pelasgus of Argos, to avoid unwanted marriages to their Egyptian cousins. However, Pelasgus is initially unconvinced of their Greekness because of their dress and skin tone. It is only after their knowledge of Greek customs and religious practices becomes apparent and their threats of suicide, as Greeks believed suicide caused pollution to the area, that King Pelasgus acknowledged their Greekness and agreed to protect them despite his initial reservations based on their skin colour.

Skin Tone and Othering in Ancient Greece

Janiform cups or kantharoi provide an interesting case study on the intersections between skin tone, culture, identity, and gender from the perspective of a Greek man. These dual-faced drinking cups made of ceramic were primarily used during symposiums by Greek men and allowed symposiasts to briefly don a “mask,” like actors on an Athenian stage, of the “other” − anyone who was not a Greek man. Common combinations include godly or heroic figures associated with drunkenness, like Herakles, Dionysus, or satyrs, or cultural others as represented by their gender, features, and skin tone, such as Greek women and Aithiopians of both genders. The Janiform cup in Fig. 13.3 features an example of a pale Greek woman and a dark Aithiopian or African man who can be identified by his skin tone and distinct hairstyle. The interplay between these combinations demonstrates how Greek men constructed the “other” as anyone who did not appear like them, with tanned skin and culturally similar practices. Someone to play at, but, in their view, never be.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Davidson, J. 2012. “Bodymaps: Sexing Space and Zoning Gender in Ancient Athens.” Gender & History 23.3: 597-615.

Derbew, S. F. 2022. Untangling Blackness in Greek Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eaverly, M. A. 2013. Tan Men/Pale Women: Color and Gender in Archaic Greece and Egypt, a Comparative Approach. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Glazebrook, A. 2009. “Cosmetics and Sôphrosunê: Ischomachos’ Wife in Xenophon’s Oikonomikos.” The Classical World 102.3: 233–48.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Resinski, R. 1998. “Cosmos and Cosmetics: Constituting an Adorned Female Body in Ancient Greek Literature.” Ph.D. diss., University of California.

Tanner, J. 2011. “Race in Classical Art.” Apollo Magazine Ltd 173: 24-9.

Thomas, B. 2001. “Constraints and Contradictions: Whiteness and Femininity in Ancient Greece.” In Women’s Dress in the Ancient Greek World, edited by L. Llewellyn-Jones, 1-16. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales.