15 Want to Know How I Got These Scars?

Wesley Prankard

While he was hunting, a boar had struck him with his white tusk when he had gone to Parnassus with the sons of Autolycus. This scar the old dame, when she had taken the limb in the flat of her hands, knew by the touch, and she let fall the foot….she touched the chin of Odysseus, and said: “Verily thou art Odysseus, dear child, and I knew thee not, [475] till I had handled all the body of my lord.” (Hom. Od. 19:465-476).

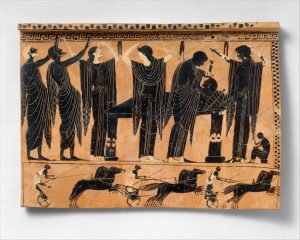

This passage is an important scene in Homer’s epic, The Odyssey. The story, also pictured to the right on a terracotta plaque (Fig. 15.1), depicts Odysseus’ childhood nurse recognizing him through his disguise, which he donned upon reaching home from his long journey. The scar originated from a hunting incident when he was a child. One aspect of this tale that seems to be overlooked is the fact that Odysseus was a war hero, so he likely had many scars. His recognition by his old nurse demonstrates the variability in a scar’s meaning. To a random observer, the scar on Odysseus’ foot would have been one in a million, but to the nurse, it transformed into a meaningful marker, a brand upon the bearer tied to the shared context the bearer and observer each held. The ancient Greeks did not practice intentional scarification (see chapter 14 on tattoos), so this chapter will explore some specific scars as healed injuries which were prevalent in Ancient Greek culture, exploring what they both told, and didn’t tell about their bearers.

Mourning the Dead: Performance Art with Permanent Implications

This terracotta plaque (Fig. 15.2) has familiar imagery associated with ancient Greek funerals. Notable are the many women gathered around the body, arms raised to their foreheads. That pose is a visual representation of mourning: tearing at the hair and scratching the skin of the face. What’s really interesting about the pose is that it became commodified through the use of paid mourners! So much so that Solon, when tackling issues surrounding oligarchy in Athens, set parameters around how many women could be hired to perform these acts at funerals in order to limit displays of excessive wealth. Before Solon’s reforms, and certainly after, as it would have been more rare, permanent lacerations on a woman’s cheeks would point to her occupation (although this ritual was not exclusive to “professional” mourners, those who were would have much stronger scars compared to someone mourning once or twice). These scars were self-inflicted, unlike some other scars that are connected to particular injuries, like cauliflower ear, which will be discussed later, and were particular to women and mortuary ritual. A man with similar scars would not be assumed to be a lamenter. It is clear then that, in a broader sense, these scars are similar to Odysseus’s. They tell a specific story about the person, but stripped of their social contexts, they become meaningless to the observer.

Cauliflower Ear: Identifying Wrestlers For Thousands of Years

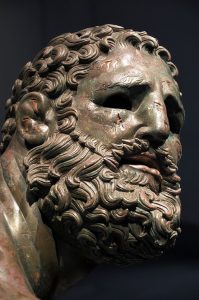

Very similar to the scars from professional lamenting, cauliflower ear immediately identified a particular activity. Cauliflower ear is formed from repeated trauma to the ear, causing the tissue to permanently swell, and the ear to protrude outward from the head. The only time cauliflower ear is shown in ancient Greek art is in relation to wrestling and fighting for sport, like this Hellenistic bronze statue of a boxer at rest (Fig. 15.3). Similar to the scars from lamenting, cauliflower ear had very specific ties to an action/profession. A Greek person could look at an individual with this scar and safely assume their connection to boxing or wrestling. Like the scars from lamenting, cauliflower ear is gendered and its interpretation relies on a context specific to an athletic fighter, which in Ancient Greece was always a man. Much like how a man with scars running down his cheeks may not be immediately associated with lamenting, a woman with cauliflower ear might confuse the observer. This is then another example of how even very particular scars rely on another piece of context to tell their full story.

Herakles The Boxer

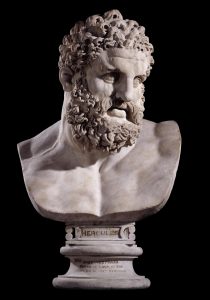

An interesting note about cauliflower ear is that Herakles is often depicted with it! As seen in this Roman copy of a Greek original, where Herakles is depicted with swollen ears, it invokes myths in which he wrestles large beasts such as the Marathon Bull, and other mythological creations like the Lernean Hydra. An example of one of these stories is when Herakles wrestled Antaeus, a son of Poseidon and Gaia. Antaeus would challenge travellers and, upon defeating them, would use their skulls to decorate his temple to Poseidon. Because of his relation to Gaia, as long as Antaeus was touching the ground, he was invincible. Herakles then lifted Antaeus off the ground during their match, crushing his ribs in the process and defeating him.

The Mark of Enslavement: How Whipping Forms Status

Socrates said that a slave can be identified even in the after life through the scars they’ve obtained via punishment (Plato. Gorg. 524C). A common punishment for enslaved people was whipping. In fact, whipping was so normal in Greek society that most of Aristophanes’ plays use the whipping of slaves for comedic effect. The punishment was also used as a major plot point like in Frogs, where the slave Xanthias defeats his master Dionysus after provoking him into a whipping competition (Ar. Frogs 605). The author Virginia J. Hunter confirms that whipping was a specific punishment for slaves, and in rare cases foreigners, but never free citizens. This would mean that the scars enslaved people carry via whipping are in fact unique. Much like lamenting scars or cauliflower ear, the scars from whipping would identify the person’s specific role in society, in this case as a slave. Unlike lamenting scars or cauliflower ear, whipping scars would have a negative association, lowering the scar-bearer’s status within Ancient Greek society.

Battle Wounds to Show Off, or the Mark of a Coward?

The Roman writer Claudius Aelianus writes that Spartan mothers, when collecting their fallen sons from the battlefield, would leave them behind or otherwise secretly bury them if they had scars on their back (Ael. VH 12.21). The sentiment here is likely that scars on one’s back would be related to injuries obtained while fleeing, and thus not be honorable. This sentiment likely comes from the strict organization of the phalanx battle. Soldiers would form a wall of sorts with their shields by standing side by side, pushing forward into the battlefield with their spears pointed toward the enemy at all times. In this formation, a soldier would either push through the enemy front-lines, or fall, allowing the soldiers behind them to take their place. With this formation scars on the back would mean the soldier had turned tail, as there would be no other way the enemy could get to their back. A conclusion could be made then that perhaps scars on the front were associated with brave acts in battle and a commitment to never wavering from the phalanx formation, whereas scars on the back had connotations related to cowardice or weakness. This association is unique, as battle scars on the front of the body would elevate the scar-bearers status, whereas scars on the back would diminish it, similar to whipping scars.

Do Scars Have Meaning Without Context?

This chapter has introduced four distinct types of scarring: mourning lacerations, cauliflower ear, slave marks, and battle wounds. In all four cases these scars are tied directly to very specific contexts, much like how Odysseus was recognised by his hunting scar, each of these scars help identify the status and role of the person bearing them. They enhance that status when associated with an athlete or a pious ritual lamenter, but in other cases diminish it because of a scar’s association to slavery, or cowardice in battle. These scars in a sense are just healed injuries, but within the context of Greek society they evolve into broader representations of groups of people.

Bibliography and Further Readings

Hunter, V. J. 1994. Policing Athens: Social Control in the Attic Lawsuits, 420–320 B.C. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sijakovic, D. 2011. “Shaping the Pain: Ancient Greek Lament and Its Therapeutic Aspect.” Glasnik Etnografskog Instituta SANU 59.1: 71–96.

Varto, E. K. 2005. “The Funeral Legislation of Solon and the Pursuit of Eunomia.” Master’s thesis, University of Ottawa.