1 The Scent of Status: Perfume and Scented Oils in Ancient Greece

Lucie Mackintosh

He really bathes in a large gilded tub….and steeps his feet and legs in rich Egyptian unguents; his jaws and breasts he rubs with thick palm oil, and both his arms with extract sweet of mint; his eyebrows and his hair with marjoram, his knees and neck with essence of ground thyme.

Athenaeus, The Deipnsophists, 15.40.

In ancient Greece, perfume was more than a fragrance—it was an emblem of wealth and status. Only the wealthy, who had the means to afford such luxuries, could indulge in the use of perfume. At its core, perfume was crafted from olive oil, but it was the art of transforming this staple of daily life into luxurious scented oils that elevated it into a coveted commodity. Beyond its culinary uses, olive oil served as the base for perfumes, cosmetics, and medicines, its versatility making it an integral part of Greek society. Yet it was the perfume—the carefully blended scents, the vessels that held them, and the rituals surrounding their use—that became the ultimate symbol of luxury, marking a clear division between the wealthy elite and everyone else—including the enslaved individuals whose labour made such opulence possible.

Crafting Scent: Art and The Economy of Perfume

While perfume itself was easy enough to create, producing the olive oil necessary to make perfume required considerable labour. Fig. 1.1 of an Attic black-figure skyphos depicting two workers pressing olives highlights the labour-intensive process of oil extraction that was vital for creating perfumes.

Much of our knowledge about ancient Greek perfumes comes from the 5th-century BCE philosopher and naturalist Theophrastus, whose treatise On Odours details the ingredients and methods used in perfume-making. He explains that oils were chosen as the base for perfumes because they preserved scents for long periods. Egyptian or Syrian balanos oil was highly prized for its low viscosity and mild scent, while fresh olive oil from “coarse olives” and the more pungent oil from bitter almonds were also used. Preparation techniques, however, like cooking or adding additional ingredients, could neutralize these undesirable qualities.

Some aromatics from spices and plants used in the production of perfume include (but were by no means limited to) cassia, cardamon, cinnamon, iris, saffron-crocus, marjoram, anise, styrax, and balsam. Aromatics were also combined to create complex and layered scents. Many ingredients used in perfume-making were not native to Greece, but imported through Mediterranean trade networks. Perfumes made from imported ingredients were more expensive than those made with local ingredients, which in turn made these perfumes all the more luxurious and sought after.

Captive Aromas: Enslaved Labour and the Hidden Cost of Luxury

The production of perfume in ancient Greece was heavily reliant on the skilled labour of enslaved and freed persons. While the technology for making perfume was relatively straightforward, the process required specialized knowledge that enabled skilled workers to travel across the Greek world in search of higher demand, helping to establish perfume production as a mobile and profitable enterprise. The cost of ingredients combined with the expertise of the workers, meant that perfume remained primarily accessible to only the wealthy. The exploitation of enslaved labour was integral to the profitability of the industry, with enslavers controlling both the production and distribution of these luxury goods. In this context, the perfume trade not only provided significant economic rewards but also reinforced social hierarchies, with enslaved persons playing a central role in the production of luxury items while remaining marginalized in the wider social structure.

Hyperides’ Against Athenogenes offers a particularly telling example of enslaved individuals’ roles in the perfume industry. In this case, an enslaved worker named Midas had been entrusted with managing a perfume shop and accrued significant debt without the knowledge of his enslaver, a metic (a non-Athenian resident) named Athenogenes. In response, Athenogenes sold Midas and his sons to avoid the debts (Hyp. 3 7–9). This instance is significant for several reasons. Midas’s ability to manage a perfume business independently of his enslaver demonstrates a rare level of autonomy for an enslaved person. It also speaks to the valuable skill set that enslaved individuals brought to the perfume trade, as their expertise was crucial to its success. The sale of Midas and his family further illustrates that enslaved individuals, even those skilled in luxury trades like perfume-making, remained subject to the whims of their enslavers, regardless of their economic contribution.

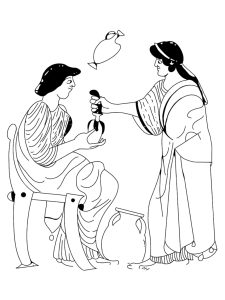

Fig. 1.2 depicting two women buying and selling perfume offers a powerful visual representation of the role of enslaved individuals in the perfume trade. While we do not definitively know the seller’s status, her cropped hair suggests she is enslaved (see Chapter 10 for more on hair). This image highlights the intersection of luxury and social status: while perfume was a symbol of elite wealth and identity, the enslaved labour behind its production and sale remained largely invisible. As the image suggests, enslaved labourers could be tasked with selling such commodities, highlighting both their centrality to the industry and the ways in which their labour was commodified.

Storing Scent: Ancient Greek Perfume Bottles

Perfumes and scented oils were stored in a wide range of vessels, each designed for specific purposes. The variety of these containers reflected the diverse uses of perfume—ranging from daily grooming and adornment to athletic care, ritual practice, and funerary rites.

Among the vessels designed for personal use, the alabastron stands out for its distinctive elongated, cylindrical body and narrow neck. Its frequent depiction in scenes featuring women in domestic or adorning contexts reinforces its association with personal grooming and feminine beauty rituals. Often lacking a flat base, the alabastron was meant to be carried by hand (as seen in Fig. 1.4) or suspended from a strap (Fig. 1.2), emphasizing both its portability and its integration into daily routines.

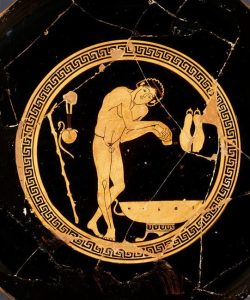

Similarly, the aryballos, a small, round flask with a narrow neck and a broad, disk-shaped mouth, was especially popular among athletes. Regularly depicted in vase paintings of gymnasium scenes (Fig. 1.3), the aryballos was likely used to store perfumed oil for application after exercise. Athletes would oil their bodies and then use a strigil, a curved metal scraper, to clean the skin—a process both cleansing and soothing.

The lekythos, another vessel designed with a narrow neck and single handle, was used in both personal adornment and ritual contexts. It commonly stored oils and perfumes, but its presence in funerary scenes and grave offerings speaks to its symbolic role in honouring the dead. The oil it held may have been used to anoint the body or left at the grave as a fragrant offering, perhaps linking scent to memory and commemoration.

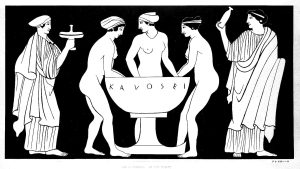

Commonly used in overtly ritual contexts, the plemochoe served a specialized function with its broad, shallow body, turned-in rim, and tall stem. Some evidence suggests that this vessel type was the preferred cult vase for dedications to Demeter and Kore during the rituals of the Eleusinian Mysteries. Its appearance in adorning scenes, however—as in Fig. 1.4—suggests that it may also have been used for personal grooming.

Lastly, the amphoriskos—a small, two-handled amphora with an oval belly and narrow neck—was used to store perfume and oil. Despite its shape and diminutive size, it was less portable than other containers and may have been intended for display or storage rather than regular transport, perhaps reflecting a more luxurious or ornamental use of scented products.

Through their forms and functions, these containers not only preserved the valuable contents within but also communicated social roles, ritual practices, and the sensory dimensions of ancient Greek life.

What’s That Smell? Perfume and the Gendered Politics of Scent

Perfume and scented oils played a significant role in both personal hygiene and social practices in ancient Greece. The application of these oils, particularly in connection with bathing, was an essential part of daily life for those who could afford it. Bathing and anointing oneself with oil were acts of both physical and social care, reflecting refinement, good health, and a sense of well-being. These practices were not only about cleansing and refreshing the body, but also about enhancing one’s appearance and social status.

The use of perfume was often gendered, with different practices and expectations for men and women. According to Theophrastus, women preferred perfume made from strong aromatics such as myrrh, sweet marjoram, and spikenard, as these lasted longer on the body. Men, however, favoured lighter scents such as rose and lily (Theophr. Sens. 10.42). While both genders used perfume as a means of personal care and social signalling, there were significant differences in how and why they used these fragrant oils.

For women, perfume played a central role in the concept of beauty and femininity. The application of perfumes was often associated with rituals of personal adornment, particularly in the contexts of social gatherings and marriage. Perfume not only enhanced physical appearance but was also a marker of sexual desirability. Fig. 1.4, which depicts women bathing with attendants holding perfume containers – the plemochoe and the alabastron – on either side, illustrates the expectation for women to present themselves not just as visually appealing, but appealing to all senses, including smell. The use of perfume enhanced their attractiveness and, in turn, contributed to their perceived value in society.

Men’s use of perfume, on the other hand, was tied to different ideals, often reflecting notions of strength, power, and masculinity. In the gymnasium and athletic arenas, men used scented oils for grooming, especially after physical exercise. These practices were symbolic of not just cleanliness and hygiene but also strength and virility, and social standing. Using high-quality, imported perfumes and scented oils was a symbol of a man’s wealth and elite status.

For men, however, wearing perfume was not without tension. In Xenophon’s Symposium, Socrates critiques the use of perfume by arguing that, “the odours appropriate to men and to women are diverse,” and “so far as perfume is concerned, when once a man has anointed himself with it, the scent forthwith is all one whether he be slave or free” (Xen. Sym. 2.3). Socrates’ commentary implies that perfume undermines the distinction between classes and genders, eroding the markers of male superiority and social order. For men, he argues, the smell of olive oil and exertion—products of the gymnasium—are more appropriate than artificial fragrance, which he associates with luxury, femininity, and even effeminacy.

The nude athlete, depicted in Fig. 1.3, post-bath, offers a visual counterpart to this ideal. Though we cannot say for certain whether the oil in his aryballos was perfumed or simply olive oil for athletic use, the image nonetheless emphasizes the connection between male grooming, physical exertion, and elite status. Nevertheless, the act of anointing the body after exercise symbolized discipline, health, and a socially sanctioned form of bodily care—one that contrasted sharply with the perceived indulgence of perfume as a feminine or luxurious excess.

Law vs. Luxury: Solon’s Unsuccessful Ban

In the early 6th century BCE, Solon, the famous Athenian lawmaker, enacted a law which sought to legislate the perfume industry, and in particular, to prohibit men from trading in perfumes.

On one hand, there may have been an economic motivation behind the ban. Some scholars have suggested that growing the flowers and aromatic plants used for perfume production required large tracts of land, land that could otherwise be used for the cultivation of essential crops like grain, potentially harming the economy by limiting food production.

On the other hand, the law could have been intended to discourage men from engaging in trades that were associated with luxury and excess. Solon may have believed that perfume production was too closely tied to elite, leisure-oriented consumption, which he may have seen as inappropriate for men involved in public life. This law, therefore, may have been intended to preserve traditional roles by discouraging men from engaging in what were perceived as excessive or non-essential trades.

Ultimately, Solon’s ban was unsuccessful because perfume had already become well-established as a luxury good. People either appreciated the scent of perfume itself, the social distinction it provided, or the wealth generated from its trade—perhaps all three. This made perfume too valuable to be restricted by law.

Scent and Society: Perfume’s Lasting Legacy

Examining the perfume industry in ancient Greece reveals its deep entanglement with gender, status, and labour. While perfumes and scented oils were luxury goods that signified elite status, their production relied on labour often performed by enslaved individuals whose contributions remain largely unacknowledged in ancient sources. The tension between perfume’s desirability and its association with luxury is evident in attempts like Solon’s failed ban, which sought to regulate its trade but ultimately reinforced its economic and social significance. Both literature and material evidence demonstrate the cultural perception of scent. Perfume was not merely an aesthetic indulgence but a marker of identity that reinforced distinctions of class, gender, and citizenship in the ancient Greek world.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Aktseli, D., and E. Manakidou. 2021. “Aromatic Plants, Perfumes and Perfume Vases: Their Uses in Everyday and Religious Life during Archaic and Classical Times.” In Kallos: The Ultimate Beauty [exhibition catalog], edited by N. C. Stampolidis and I. D. Fappas, 295–315. Athens: Museum of Cycladic Art – Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Brun, J.-P. 2000. “The Production of Perfumes in Antiquity: The Case of Delos and Paestum.” American Journal of Archaeology 104.2: 277–308.

Foxhall, L. 2007. Olive Cultivation in Ancient Greece: Seeking the Ancient Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leão, D. F., and P. J. Rhodes (ed. and trans.). 2015. The Laws of Solon: A New Edition with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. London: I. B. Tauris & Co.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, S. 2002. The Athenian Woman: An Iconographic Handbook. London and New York: Routledge.

Llewellyn-Jones, L. 2003. Aphrodite’s Tortoise: The Veiled Woman of Ancient Greece. Swansea: The Classical Press of Wales.

Massar, N., and A. Verbanck-Piérard. 2013. “Follow the Scent… Marketing Perfume Vases in the Greek World.” In Pottery Markets in the Ancient Greek World (8th–1st Centuries B.C.), edited by A. Tsingarida and D. Viviers, 243–68. Bruxelles: CReA-Patrimoine.

Mitsopoulou, C. 2012. “Cult Vases of the Eleusinian Mysteries (Plemochoai) from Alexandria in Egypt.” Paper presented at the 9th Scientific Meeting on Hellenistic Pottery, Thessaloniki, 5–9 December.

Oakley, J. H. 2020. A Guide to Scenes of Daily Life on Athenian Vases. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Papadopoulos, M. A., and D. K. Georgiou. 2023. “Scented Legends: A Journey of Perfumery from Myth to Antiquity.” American Research Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 11.3: 17–29.

Reger, G. 2005. “The Manufacture and Distribution of Perfume.” In Making, Moving, and Managing: The New World of Ancient Economies, edited by Z. H. Archibald, J. K. Davies, and V. Gabrielsen, 253–97. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Rimmel, E. 1867. The Book of Perfumes. London: Chapman & Hall.

Scarborough, J. 1986. “Early Greek Perfumes.” Pharmacy in History 28.3: 15–24.

Totelin, L. M. V. 2009. Hippocratic Recipes: Oral and Written Transmission of Pharmacological Knowledge in Fifth- and Fourth-Century Greece. Studies in Ancient Medicine 34. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Voudouri, D., and C. Tsesmeratis. 2015. “Perfumery from Myth to Antiquity.” International Journal of Medicine and Pharmacy 3.2: 41–55.