8 Did Hoplites Dress to Impress? Ancient Greek Military Dress

Luke Foreman

The hoplite soldiers of Archaic and Classical Greece may not have been wearing designer brands, but that does not mean their battlefield attire was lacking in taste or style. Perhaps the most recognizable element of the hoplite panoply was the bronze-moulded cuirass. It was more than just protection; it was a statement of wealth, status, and identity. Wearing such armour marked the soldier as a citizen of the polis and stood in stark contrast to the appearance of the barbarian ‘other.’ Additionally, the aspis (shield), dory (spear), and xiphos (short sword), along with greaves and a helmet, were essential components of the hoplite’s martial wardrobe. This military garb was not fixed; it was dynamic and evolved across different regions and periods, reflecting local needs, resources, and styles.

Hoplites, Armour, and Weapons

Hoplites were Greek citizen-soldiers called to serve in times of war by the polis (city-state) in which they lived. The hoplites are most famous for the phalanx formation, which required a tightly packed line of soldiers, several ranks deep, who protected one another with overlapping shields and advanced with their spears. Only free, able-bodied male citizens were eligible to serve, and physical fitness was essential to maintain the discipline and coordination demanded by the phalanx. Since hoplites were typically expected to provide their own equipment, a certain degree of wealth was necessary to afford the full panoply.

While there were many variations in arms and armour a hoplite could choose from, certain pieces became standardized or widely used. One example is the Corinthian-style helmet (Fig. 8.1), typically made of bronze or leather. Bronze greaves were shin pads that would cover from the top of the knee to the top of the foot. Wealthier soldiers would have worn a bronze cuirass, like the piece shown in Fig. 8.2. As for weaponry, hoplites typically carried two to three dorata with bronze or iron heads; the extras were carried as backups in case of breakages. A xiphos, a short sword, served as a secondary weapon in close combat if all dorata were broken or as a last resort. Finally, each hoplite carried an aspis, a large circular shield held in the left hand, which protected both the bearer and the soldier to their left in the phalanx formation.

The Cost of a Soldier

Before Athens began state-sponsored distribution of arms, becoming a hoplite was restricted by personal wealth. Although it was possible to enter battle without armour, the essential equipment, a dory and aspis, was compulsory and could cost between 25 and 30 drachma, roughly equivalent to a month’s wage for a skilled labourer. A full set of armour would have cost even more, approximately 75–100 drachma.

Ahmed Hafez argues that the motivation for becoming a hoplite extended beyond civic duty or economic gain; for many, it was a means of differentiating themselves from the lower classes of troops, such as archers, slingers, and other lightly armed soldiers who were not able to enjoy the same prestige. This connection between wealth and military identity underpins what some scholars refer to as the “hoplite class,” referring to those who could afford the cost of participation. However, it would be misleading to interpret this group as a cohesive middle class. Greek society was typically divided between a wealthy elite who did not need to work and a lower class who laboured for a living. While some sources gesture toward a middle class, its role in the context of hoplite warfare appears limited. As Aristotle observes in his Politics, “in the city-states the middle class is small; either the propertied class or the common people are always dominant” (Aristot. Pol. 4. 1296a).

Armour for Protection or Show?

While one may assume that bronze armour offered superior protection compared to leather alternatives, this was not always the case. The bronze was often hammered so thin as to reduce weight, which made it less effective against piercing weapons such as spears and arrows. This can be seen in an especially thin bronze helmet in Fig. 8.1. If this is true, why would any soldier buy the expensive bronze armour rather than more affordable leather?

The scholar van Wees argues that the appeal of bronze lay in its ability to communicate messages of wealth, privilege, and social distinction. Wearing bronze armour signalled one’s identity as a hoplite and set them apart from lower-class troops such as archers or slingers, who were often viewed with less respect in Greek society. Xenophon, in his Constitution of the Lacedaemonians, remarked that bronze was chosen for hoplites specifically for its polish and resistance to wear, omitting any mention of its protective strength (Xen. Const. Lac. 11.3). This supports the view that hoplites wore bronze armour for non-practical reasons like its shine, permanence, and aesthetic appeal.

Additionally, bronze armour and shields often bore engraved or painted imagery designed to intimidate the enemy. Shields frequently depicted gorgons, mythological figures, or sacred symbols, serving both to frighten opponents and to express the wealth and piety of the wearer.

Military Dress and Identity

The final reason Greeks may have taken such pride in their distinctive hoplite armour was its ability to visually differentiate them from the ‘other,’ the so-called barbarians, a term used by the Greeks to describe all non-Greek-speaking peoples.

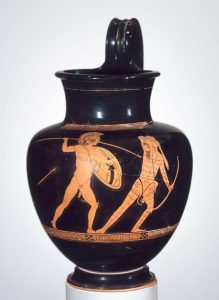

This distinction was not only linguistic or cultural but also visual and ideological, especially after the Persian Wars in the early fifth century BCE, when Greek identity became increasingly defined in contrast to the East. Fig. 8.3 illustrates this contrast in dress and status between a Greek hoplite and a Persian archer. On the left, the hoplite is depicted in the idealized form of heroic nudity, carrying a spear, shield, and helmet that symbolize courage, discipline, and Greek identity. On the right, the Persian figure wears patterned clothing, trousers, a soft cap, and carries a bow. These features signalled foreignness, and the bow, in particular, was viewed by Greeks as a less honourable weapon since it did not require close-quarters combat. This imagery reinforces the perceived superiority of the Greek hoplite by presenting him as the embodiment of martial strength and virtue, while the Persian figure serves as a visual contrast, highlighting the foreignness and supposed inferiority of non-Greek modes of dress and warfare.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Cartledge, P. 2013. Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hafez, A. G. 2015. “The Social Position of the Hoplites in Classical Athens: A Historical Study.” Athens Journal of History 1.2: 135–46.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Snodgrass, A. M. 1967. Arms and Armour of the Greeks. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Wees, H. van. 2004. Greek Warfare: Myths and Realities. London: Duckworth.