17 It’s All About the Bling: Jewelry in Ancient Greece

Kathy Pye

The first pieces of jewelry worn were natural, unworked, organic materials such as nuts, bones, teeth, and shells, leaving us with the question: What came first, jewelry or clothes, and why did people wear it? Was it for adornment and beauty? Or was it worn as a magical medium to either attract protection or ward off evil, or was it a bit of both?

The abundance of gold in Egypt and Asia gave rise to the desire to wear gold as adornment in the Mediterranean. In ancient Greece, its luminous nature made it the most precious metal due to its brilliance (Sappho called gold “the child of Zeus” (Sappho Frag. 31), and it was favoured as an adorning metal due to the tarnishing tendencies of silver. Gold, or khrysos as the Greeks referred to it, was believed to have supernatural properties, and those who wore it were immortal. In mythology, wearing gold was associated with the positive characteristics of heroic figures who donned gold belts, sandals, and swords. However, luxury items remained rare in Greece until 900 BCE, when there was an increase in the trade and importation of foreign luxury goods. It was not until after the Persian Wars of 490 BCE that jewelry gave way from an apotropaic, or protective function, to a form of adornment in Greece.

The Phoenicians were prized for their goldsmithing, and Greek artisans likely borrowed their techniques. Work was often done in a small shop where a master craftsman would oversee artisan-trained apprentices, freedmen, and enslaved persons who worked with the highly malleable metal, hammering it into various thicknesses and turning it into the gold wire, which could be braided or twisted to form a rope. Other popular decorative techniques included embossing using a stamp, granulation involving melted globules of gold wire, and soldering or gluing the globules to outline figures or form a geometrical design (video). Designs of the archaic and classical periods were understated. It was after the conquests of Alexander the Great in the Hellenistic period when trade between Mediterranean countries exploded, creating vast availability of precious metals and gemstones, that jewelry design became more ornate and metropolitan.

Types of Jewelry

Earrings were the only type of adornment that required a modification to the body. Despite being worn by both sexes in other ancient cultures, Greek women only wore them (see chapter 16 on piercing). Initially, they were simple in design and worn by feeding a fine wire through the earlobe upon which elongated spirals or geometric designs were hung, or they terminated with an animal or god motif, as illustrated in Fig. 17.1.

Moving through the archaic and classical periods, styles became more elaborate, involving multiple goldsmithing techniques such as using granulation, as seen in Fig. 17.2, which illustrates a more complex design involving figures hanging from a gold disc and the appearance of more enhanced design techniques. The later classical period and the early Hellenistic times saw a heavy design influence from other cultures, such as Egyptian. As competition for luxury goods increased, craftsmen competed for market share, resulting in greater imagination in design. Common themes during the Hellenistic period were plant and animal motifs, the relationship between Aphrodite and Eros, and winged deities such as Nike.

Bracelets were worn by women either above the elbow or around the wrist. Initially, they were simple wire or sheet metal wound into a single spiral, with plain or decorated ends. With the increased interest in Eastern cultures, particularly Egypt, the snake became a popular design. It progressed from the head to the whole body, winding its way up the arm.

Necklaces were popular with women. Before the fourth century BCE, the beads and pendants of Greek necklaces were usually strung on perishable strings, which suggests that gold or some precious stone could be removed in case of financial need. The onset of the development of gold wire led to loop-in-loop chains. Artisans created the chains by creating individual gold loops that could be passed through one another to form a chain. As techniques advanced, artisans were able to twist the looped wires together, adding beads to create more ornate pieces.

Both sexes wore rings. After the conquest of Egypt in 323 BCE, the Greeks adopted the Egyptian practice of giving rings as tokens of friendship and affection while signifying a bond of respect. Initially, rings were plain bands of bronze, silver, or gold and were designed to be worn daily. They then evolved to bear designs of mythological figures or natural elements. Initially, plain bands evolved into bands with open filigree and bezel designs. The archaic period started the wearing of intaglio, or seal rings, which were predominantly worn only by men.

Gemstones

Gemstones in jewelry were not common until Alexander’s conquests. His defeat of the Persians opened up gold and gem resources to the rest of the Mediterranean. Gemstones were not only treasured for their economic value but also had social and cultural significance as they were not simply ornamental but a marker of personal authority. Additionally, gemstones held a strong apotropaic role for the Greeks. Aristotle believed emeralds increased business success and would bring victory, and this belief led Alexander the Great to wear a large emerald in his belt. Sapphires were thought to open the third eye, allowing communication with the spirit world, and were worn by Greeks when visiting the Pythia at Delphi. Greek philosopher and naturalist Theophrastus, in his work “On Stones,” discussed the apotropaic significance of certain gemstones in adornment as well as proclaiming their value stemmed from their primary characteristics of colour and luminosity, with specific colours such as red being held in higher esteem than others. The Greeks also believed that stones could be divided into male and female according to their depth of colour, with the darker, richer ones being male and the lighter female.

Who wore it and why

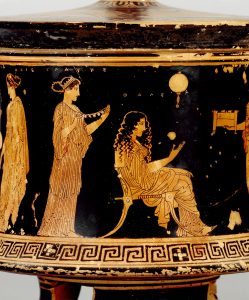

Jewelry was a marker of gender, worn predominantly as a luxury item by women as self-adornment. Visual images confirm an association between women and jewelry in marriage, wherein their preparation for the wedding included choosing jewelry, illustrated in the vase painting in Fig. 17.3.

Women adorned themselves for four reasons: beauty, sexuality, fertility, and wealth. In Greek culture, a woman’s attractiveness was a highly valued asset, and jewelry could enhance her physical appeal. Ancient Greek women identified Aphrodite as the mentor of beauty, and the goddess was always adorned with jewelry (HH 5.65). While a woman might not have been as naturally beautiful as the goddess, it was thought that if she adorned herself with exquisite jewels, she would appear attractive to others. The jewelry bore many plant and animal motifs, such as pomegranates, blossoms, and tendrils, symbolizing a woman’s fertility. The appearance of Eros and Aphrodite connected the wearer with the god and goddess to express sexuality. Jewelry also indicated the social status of the woman and her husband, who was more restricted in his adornment. The woman’s jewelry reflected the wealth of the household.

The more flamboyant and opulent a woman’s jewelry was, the wealthier her husband and the higher his social status. However, there were no laws restricting what jewels the various social classes were allowed to wear, so jewelry on its own could not demarcate whether the wearer was a respectable wedded matron or a wealthy hetaira (paid sexual companion), like Neaira, who might receive gold jewelry as gifts of affection (Dem. 59.35). Jewelry for men was confined to signet rings. They were a sign of their status and importance, as these rings were used as a business symbol and identified the wearer. In Sophocles’ play, Elektra recognizes that her brother Orestes has returned only when he shows her the seal of their father Agamemnon (Soph. El. 1222-24).

Glyptiks

Cameos and intaglios were the predominant glyptiks of Ancient Greece. Glyptiks refers to precious stones that have been carved, with intaglios carved into the stone and cameo carvings convex in that the craftsman cut away the stone to provide a relief carving.

Intaglios were designed to create seals and had ornamental images carved into them, often in reverse, so the resulting image would be seen correctly when they were set into a substance such as wax. Usually, the image was complex to see in the gemstone but emerged as a straightforward portrait or scene of the substance it was set into. Frequently, these characters reflected scenes of myth or hunting. Seals were a sign of importance and social status, and although women had intaglio rings featuring scenes of nature and animals, they did not bear the same social significance as a man’s.

Cameos saw the carver cut away the excess stone, leaving behind a relief figure. This technique was more complex, and unlike the intaglio, the images were meant to be seen and recognized, as illustrated in Fig. 17.4. The craftsman would cut through different layers of stone to distinguish a foreground from the background and were able to include more details, such as hair. A skilled artisan could carve on an overlying stone band so thinly that it would appear transparent, creating light and dark contrast. Cameos were carved strictly to be worn as jewelry and were often set into rings or pendants.

The craftsmanship of glyptik carvings was highly skilled, and artisans often carved their names into the stone, thereby “signing” their creations. Artisans became famous for their work, and having a cameo or intaglio signed by a well-known artisan indicated wealth and a very high status for the wearer.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Bayoumy, T. 2020. “Highlighting Some Important Gemstones in Ancient Egypt (From Predynastic Till End of the Graeco-Roman Period).” The Scientific Journal of the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels, Alexandria University 17.2: 179–93.

Beckman, E. 2017. “Color-Coded: The Relationship Between Color Iconography and Theory in Hellenistic and Roman Gemstones.” In What Shall I Say of Clothes? Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to the Study of Dress in Antiquity, edited by M. Cifarelli and L. Gawlinski, 67–82. Boston: The Archaeological Institute of America.

Blundell, S., and N. Sorkin Rabinowitz. 2008. “Women’s Bonds, Women’s Pots: Adornment Scenes in Attic-Vase Painting.” Phoenix 62.1: 115–44.

Buitron, D., A. Oliver, and J. V. Canby. 1979. “Ancient Jewelry in Baltimore.” Archaeology 32.5: 53–56.

Castor, A. 2017. “Surface Tensions on Etruscan and Greek Gold Jewelry.” In What Shall I Say of Clothes? Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to the Study of Dress in Antiquity, edited by M. Cifarelli and L. Gawlinski, 83–100. Boston: The Archaeological Institute of America.

Contestabile, H. 2013. “Hellenistic Jewelry and the Commoditization of Elite Greek Women.” Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics 2.2: 1–13.

Despini, A. 1996. Greek Art, Ancient Gold Jewelry. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon.

Hemingway, C., and S. Hemingway. 2007. “Hellenistic Jewelry.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hjew/hd_hjew.htm.

Lapatin, K. 2015. Luxus, The Sumptuous Arts of Greece and Rome. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oliver, A. 1966. “Greek, Roman, and Etruscan Jewelry.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 24.9: 269–84.

Wagner, B. H. 2013. “Marriage Gifts in Ancient Greece.” In The Gift in Antiquity, edited by M. Satlow, 152–72. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.