10 Head Coverings: Practicality and Societal Implications

Josiah Straatsma

Hats are a common article of clothing that we interact with on a daily basis. They can serve both practical and symbolic purposes, protecting the wearer from the sun or the cold and allowing for self-expression through style, colour, and symbols of sports teams, brands, or companies. The dynamic use of hats is not new, and even in Ancient Greece they had similar functions, despite being more gendered, with certain styles only being acceptable for specific groups to wear. With all this in mind, let’s take a look at a variety of the hats worn in Ancient Athens.

Men’s Wear

Men’s hats in Ancient Athens were primarily practical. The two most common hats for citizen men to wear were the petasos (pl. petasoi), the traveller’s hat associated with Hermes in art like the linked krater from the British Museum, and the pilos (pl. piloi), the workman’s hat, which is occasionally depicted on Hephaestus as on this amphora.

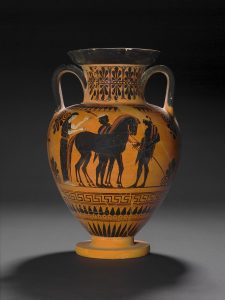

In Fig. 10.1 on the right, the man standing middle right and the man standing on the far left both wear petasoi. It was a wide brimmed hat made of straw or felt, with a cord securing it beneath the chin seen on this zoomed in image of Fig. 10.1 and could be depicted with a central knot or spike. The man on the far left wears the hat on his back with the cord around his neck to keep the hat secured while it is not on his head. This style of hat was associated with young men (ephebes), travellers, and cavalry men in the Athenian army.

The Horsemen’s Petasoi on the Parthenon Frieze

Tom Stevenson discusses the depictions of horsemen on the south frieze of the Parthenon in Athens. He uses the petasos as well as other articles of clothing to try and present the possibility of a standardized uniform for the Athenian cavalry, which contrasts the Athenian foot soldiers whose armour and gear were entirely dependent on social class as discussed in chapter 8, Military Dress. In chapter 3 of this book, Threads of War, it was mentioned that the Spartans had a standard uniform that made them an intimidating force to face. The nature of this standard uniform was made possible because of the equality of the Spartiates. The same logic could be used to explain why the cavalry, who were rich enough to afford horses and the kit required for that combat, would have a more cohesive look than the hoplites, whose use of body armour varied. Stevenson, however, debunks these ideas and explains instead that these cavalrymen are depicted as an artistic motif, using symbols and imagery to demonstrate their status as horsemen, making them more akin to caricatures by using elements that would be associated with horsemen in general. He presents this by comparing these horsemen to the other men on the Parthenon, and demonstrates that they are the most consistently clothed, wearing boots, cloaks, and petasoi. Stevenson ends by comparing these depictions to the common depictions of men riding and guiding horses on pottery as demonstrated in Fig. 10.2 to the right. In the end he concludes that the presence of clothing that may have indicated a uniform was, simply, a representational depiction, a visual shorthand to indicate the cavalry nature of these characters. His analysis and argument are based on his knowledge of what the clothing on the horsemen means. This shows how important it can be to analyze each individual piece of clothing in a work of art to determine what it can tell us about the culture that created the piece.

Women’s Wear

Women’s head coverings were more restrictive and ornate than men’s hats, making them less practical. One of the most common head coverings worn was the sakkos (pl. sakkoi), a mesh hairnet created using the sprang weaving technique. A simplified demonstration and finished result of this technique is shown in this video.

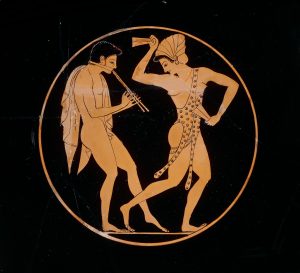

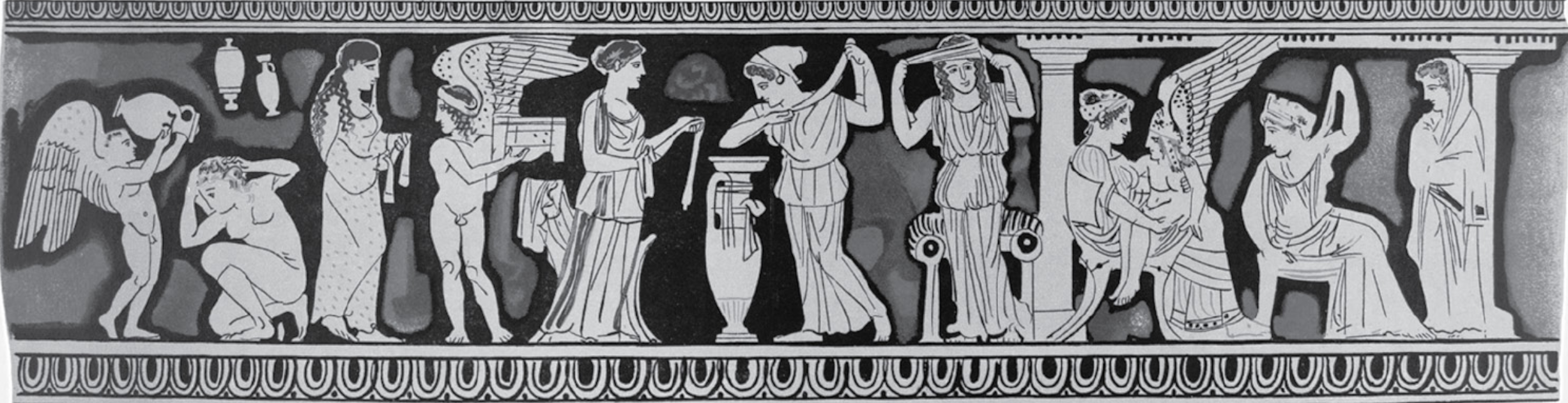

This head covering is unique because, as the video shows, the mesh style could be ornate and quite beautiful. Despite this, in Greek art, as seen on the central woman in Fig. 10.4 below, the sakkos often appears dull, little more than a bag, despite the intricate details their real counterparts would have had. The mitra (pl. mitrai) is another important head covering found in Greek art. It was a long, wide piece of fabric that would be wrapped around the head to create the turban style of head covering worn by the dancer in Fig. 10.3 to the right.

Women’s head coverings, like men’s hats, did not indicate social status through design. However, there is much discussion among scholars about how they symbolize some of the restrictions placed on women in Ancient Greece. Unlike the men’s hats, which were removed and replaced frequently throughout the day, and were often depicted in art both on and off the head, as seen on the krater above, women’s head coverings were more permanent and difficult to remove quickly. This represents one aspect of the restrictive nature of women’s dress. The analysis of these head coverings as symbolizing the societal restraints of women is exemplified not through the head coverings themselves, but through what lies beneath and the ritual binding of hair using a tainia (pl. tainiai).

Tainia and Reflection of Status

Tainiai were simple headbands. They were long pieces of fabric that were thinner than mitrai. Seen in abundance in Fig. 10.4 with many of the women holding the bands of fabric, they were used in everyday wear by women in ancient Greece, but the act of tying them in Greek art holds ceremonial importance. Fig. 10.4 above is a drawing of a pyxis (pl. pyxides) or jewelry/makeup jar from The Metropolitan Museum of Art. For the symbolic and ritual meaning of the pyxis, see chapter 20, A Vessel of Beauty. From left to right in the image, the stages of marriage preparation are visible. On the left is a woman washing herself, her hair unbound, as she is unmarried, representing the period of a girl’s life where she was not of age to be married, as described in chapter 9, Hair in Antiquity. The next segment of the pyxis depicts the woman binding her hair using a tainia. This partially bound state represents the marriageable woman. This state is best represented on the linked image of a maiden (kore, pl. korai) statue, which depicts women who are old enough to be seen as marriage candidates, but are, as of yet, unmarried, as seen in chapter 6, Get in the Zone. The remaining sections of the pyxis imagery represent her marriage and life after marriage, with her hair fully bound. This depiction is a wonderful representation of one of the ways of telling a woman’s age in Greek vase painting and statuary. This image is a fantastic reference piece for analyzing and categorizing the age range of women depicted in Greek art.

Conclusion

Greek head coverings vary depending on the occupation, gender, and age of the wearer. Understanding these differences allows for the viewer of Greek art to draw conclusions while only analyzing a small, but incredibly important part of the subject’s outfit. While greater context is still required to create more concrete analyses, understanding even just a small part adds to the understanding of Greek symbolic depiction.

Bibliography and Further Readings

Bonfante, L. 1975. Etruscan Dress. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jenkins, I., and D. Williams. 1985. “Sprang Hair Nets: Their Manufacture and Use in Ancient Greece.” American Journal of Archaeology 89.3: 411–18.

Knauer, E. 1992. “Mitra and Kerykeion: Some Reflections on Symbolic Attributes in the Art of the Classical Period.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 107: 373–99.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stevenson, T. 2003. “Cavalry Uniforms on the Parthenon Frieze?” American Journal of Archaeology 107.4: 525–46.