11 Bare Necessities: Hair Removal in Ancient Greece

Maya Granados

Hair removal is often seen as a modern beauty standard, with countless products and techniques available today to achieve smooth skin. Yet, thousands of years ago, the ancient Greeks were equally invested in managing their body hair, for reasons that extended beyond aesthetics. For Greek men and women, the presence or absence of hair on specific parts of the body carried social and religious significance. The way hair was groomed, cut, or removed was an expression of identity, marking distinctions between men and women, youths and adults, Greeks and non-Greeks. This chapter aims to explore how the removal of facial, head, and pubic hair functioned within Greek society and how these practices reflected broader cultural values.

Methods of Hair Removal

Hair removal in ancient Greece was performed through a variety of means, some of which remain familiar today. Bronze or iron razors, such as this single-bladed one, were commonly used, especially by men, to maintain their facial hair. For finer or sparser hairs, such as those around the eyebrows, plucking with tweezers, which looked very similar to the ones we use today, was common, though time-consuming and painful. Pumice stones were also used to smooth the skin and wear down finer hair. While chemical depilation methods are attested in neighbouring cultures like Egypt and the Near East, evidence for their use in Greece is scarce. Singeing, or burning away hair, was another technique and commonly done with oil lamps. You can see a woman removing hair in this way in Fig. 11.1. The practice is referenced by Praxagora in Aristophanes’ AssemblyWomen:

Thou alone shinest into the secret recesses of our thighs and dost singe the hair that groweth there, and with thy flame dost light the actions of our loves (Aristoph. Eccl. 1.12-15).

Grooming and the Greek Ideal

Ideals of beauty were closely linked to hair removal. Women and men alike were expected to have clean, groomed skin. Women were expected to be smooth and hairless, and this expectation extended to all women, regardless of class or social status. Both married women and hetairai – a type of sex worker, with hetaira (sg) meaning ‘companion’ – practiced depilation, though for different reasons. Married women maintained hairlessness as a sign of modesty and preference, in keeping with societal expectations of feminine beauty and order. Hetairai often removed body hair to enhance their sexual appeal by aligning themselves with the aesthetic preferences of men. This expectation reinforced the Greek idea that female beauty was tied to purity and careful self-maintenance, as well as the view of men. Furthermore, this reinforced that hair removal was not only a beauty standard, but also a deeply ingrained cultural practice that signified a woman’s adherence to Greek ideals of femininity and social propriety.

Men’s grooming choices often reflected their stage of life and social role. Beards and head hair were markers of age, with older men growing out their beards, and younger men wearing their hair long in childhood. They would then cut the long hair off when they reached puberty, at which point growing a beard signified entry into adulthood and maturity (see chapter 9 on Hair in Antiquity). Elite men often wore carefully groomed facial hair, distinguishing them from lower-class individuals who might have less control over their personal grooming.

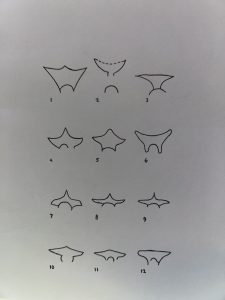

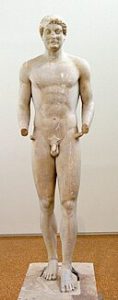

Young men and athletes frequently removed pubic and body hair to accentuate their physique, as seen in countless statues (Fig. 11.3.). Greek men’s pubic hair aesthetics were particularly significant in artistic depictions. The drawing in Fig. 11.2 shows pubic hair carved into geometric or symmetrical patterns as found on Greek statuary, and suggests actual practices for Greek men and youths, at least among the elite. These choices emphasized youth, vitality, and physical perfection, highlighting that the ideal Greek male body was both strong and aesthetically pleasing.

The Well-Groomed Greek and the Barbarian ‘Other’

Athletes in Greece were not only defined by their skill and physique but also by their carefully groomed bodies. Greek athletes trained and competed in the nude, where smooth, hairless skin was considered the ideal, as it emphasized both their youth and physical perfection. Statues such as the Aristodikos Kouros (see Fig. 11.3.) show this aesthetic preference, with the careful sculpting of its stylized pubic hair, its clean-shaven face, and the lack of overall body hair. This emphasis marked a contrast between Greek men and their non-Greek counterparts, highlighting the Greek male body as idealized and controlled, with well-groomed pubic hair serving as another means of self-discipline and civilization.

Foreigners, particularly those from Persia or other eastern countries, were often depicted with unkempt or excessive body hair, reinforcing the Greek belief in their own cultural superiority. The contrast between the carefully groomed, smooth-skinned Greek athlete and the shaggy, hairy non-Greek separated the civilized Greek from the barbarian ‘other.’ In this way, hair removal, and by extension body hair maintenance, characterized the Greek male body as a statement of control over nature and animals, as well as barbarity.

Hygiene and Health

Beyond beauty and social expectations, hair removal had practical implications for hygiene and health. In a warm Mediterranean climate, body hair could trap sweat and dirt, potentially leading to body odour and skin irritation. Removing hair, particularly in areas prone to sweat, helped maintain cleanliness. Greek athletes, who trained and competed in the nude, often removed body hair to reduce chafing and enhance hygiene during physical activity. Hair removal was also likely recommended for treating wounds or as a remedy for lice. Lice infestations were a particular concern, particularly among soldiers, travellers, lower classes, and hetairai, who either wouldn’t have had the access to bathing as frequently and encountered a lot of people more regularly. While Greek sources do not frequently mention lice removal, various ancient writers mention the practices of non-Greek peoples, such as in Herodotus’ Histories where he describes Libyan women (Hdt. 4.168) and Egyptian priests (Hdt. 2.37) protecting against lice. Removing all body hair through shaving or plucking would have been one method of preventing infestations.

Mourning, Devotion, and the Cutting of Hair

Hair removal also played an important part in ritual and personal sacrifice. Women would pull their hair out in moments of extreme grief; an act that served as a physical expression of sorrow (see also chapter 15 on scarring). Men would also cut off locks of hair to dedicate in mourning, like when Achilles dedicated his hair to honour his dead friend Patroklos (Hom. Il. 23.135-37). Similarly, the dedication of hair played a role in religious practice. Young girls might dedicate cut locks of their hair to the gods, and men sometimes cut their hair during rites of passage, symbolizing the transition from youth to adulthood. These rituals reinforced the idea that hair carried a symbolic weight – its removal could be a sign of loss, devotion, or transformation.

More than a Standard

The removal of hair in Ancient Greece was not just about aesthetics; it highlighted cultural values surrounding beauty, hygiene, identity, and ritual. Whether for aesthetics, practicality, or ritual significance, removing hair from any part of the body had a role in Greek society. The carefully maintained appearances of both men and women signified more than personal preference. The way an individual approached hair removal could communicate not only beauty but also careful self-maintenance, identity, and adherence to cultural norms. From a smooth-skinned athlete to the mourning woman pulling out her hair, with every strand removed or preserved, the Greeks expressed their values, their roles, and their places in society.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paul, J. A. 1994. “A New Vase by the Dinos Painter: Eros and an Erotic Image of Women in Greek Vase Painting.” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 3.2: 60–67.

Smith, R. R. R. 2007. “Pindar, Athletes, and the Statue Habit.” In Pindar’s Poetry, Patrons, and Festivals: From Archaic Greece to the Roman Empire, edited by S. Hornblower and C. Morgan, 112–33. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Synnott, A. 1987. “Shame and Glory: A Sociology of Hair.” The British Journal of Sociology 38.3: 381–413.