9 Hair in Antiquity

Jessica Kroeze

Hair is an important part of self-expression and adornment. Today, a person may dye or cut their hair, wear wigs, toupees, weaves or other hair pieces. These options were all available in ancient Greece as well. While in North America today, an individual may change their hair as a form of self-expression, hair in ancient Greece reflected Greek societal identity, connected to gender and rites of passage. This chapter focuses on the various hairstyles in ancient Greece and how they represent the phases of an individual’s life in Greek society.

Hair and Humours

The ancient Greeks understood health through the analogy of humours (bodily fluids). They thought that these humours (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile) travelled through the body and caused temperature fluctuations. Balancing one’s humours was important because when they were out of balance, too cool or hot, too much or too little, a person could become ill. This would affect not only their physical health but also their appearance and the physicality of their hair.

Hippocrates of Cos, also called Hippocrates II, was a physician and philosopher in classical Greece from about 460-370 BCE. In his Nature of the Child, he explains how hair is formed in utero and infancy. The Greeks believed that where skin on the body was thinnest, and humours were at the proper level to provide nutrients, hair would grow (Hippoc. Nat. Puer 54-57). This started with head and eyebrow hair. Then, when an individual reached puberty, their skin would become thinner, at their armpits, pubic region, and facial hair (Hippoc. Nat. Puer 54-57).

Hippocrates also explains how humours affect hair growth and hair loss. He explains that when men exert the physical effort to ejaculate, it causes their humours to heat up, burning out the hair follicles and causing hair loss and baldness (Hippoc. Nat. Puer 54-57). On the other side of this, men who are lustful but who do not act on their desires have thick and full hair because they do not heat and expel their humours (Hippoc. Nat. Puer 54-57). Eunuchs or castrated men do not lose their hair and are known to have thick, full hair because they do not expel or heat their humours (Hippoc. Nat. Puer 54-57). Hippocrates also explains that women have long, thick hair, even if they have intercourse, because they do not expel their humours during sex (Hippoc. Nat. Puer 54-57).

Hair and Hygiene

An important aspect of Greek hair care was diata or diet. Diaita was essentially the ancient Greek version of self-care. It included different aspects of life such as exercise, diet, and hygiene. In the care of hair, Greeks used combs, mirrors, various hair bindings (explained in chapter 10), and practiced hair removal (explained in chapter 11). They thus used many methods to protect their hair and keep it healthy.

Women gathered at fountain houses where they would wash their hair and bodies and apply scented oils to their hair to keep it clean and strong (further chapter 1). They also washed at home using portable basins filled with water.

Men’s bathing took place in bath houses at gymnasia (after exercise) and in barbershops. These places were integral to everyday life for the Greeks. Because large groups of men would be gathered there, they allowed men to get the latest gossip, philosophical ideas, and business notices, in addition to cleaning themselves.

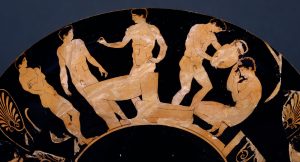

Fig. 9.1 shows athletes at the bath in a gymnasium: they are chatting, interacting, and one is pouring water from a hydria (water jug) on another man’s head while he cleans himself. The image shows the community aspect of bathing in ancient Greece. Barbershops would help men keep their beards orderly and neat. Barbers had specialized skills in hair and skincare and would help men to look their best and keep their skin and hair healthy. Although men utilized scented oils, it is uncertain whether or not they applied these oils to their hair.

Splitting Hairs: Styles and Society

Cephalic or head hair was an important aspect of an individual’s adornment (kosmos/kosmeo). Neatly-arranged hair was an indication of good, proper social order, whereas disheveled hair was a sign of disorder and disarray. Those who have been socially othered, such as foreigners, non-Greeks, elderly individuals, or enslaved persons, were depicted as bald or with unkempt and disorganized hairstyles. When looking at and trying to interpret vase paintings, the arrangements of an individual’s hair can help inform us about their societal and social status.

Hair was an important symbol of a person’s social status in ancient Greece. It is an aspect of an individual that can be changed or altered in a non-permanent manner, which allows people to show who they are within the bounds of their society. Changes were proscribed by age, gender, ritual, and sometimes status in ancient Greece. Hair provided a visual representation of different social groups, making it easier for people to know what stage of life an individual was in.

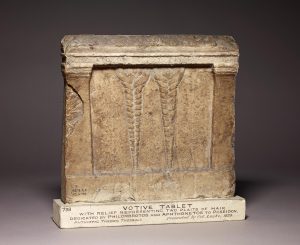

Prepubescent boys often wore their hair loose around their shoulders. As they reached puberty, they would cut their hair shorter and dedicate a piece of their shorn hair to one of the many gods tied to male maturity, such as Apollo, Dionysus, or Herakles. Sometimes people would dedicate votives shaped like hair, as seen in Fig. 9.2. They would do this as part of a coming-of-age ritual, where they would join their father’s phratry (kinship group). This practice took place during the yearly celebration called Apatouria. Plutarch, in his Life of Theseus, explains that boys would only dedicate the forepart of their hair.

Plutarch goes on to explain that young men might even travel to Delphi to complete this sacrifice, indicating it was to the god Apollo, since he was the main god worshipped there (Plut. Thes. 5.1). Adolescents were expected to have short, well kempt hair as a sign of maturity and safety during war. Spartan boys, however, did the opposite: their hair would initially be kept short, and would be grown out during adulthood. Some ancient authors believed that Lycurgus, who was the semi-mythological Spartan lawmaker, required Spartan men to wear their hair long to appear larger, more intimidating, and more dignified.

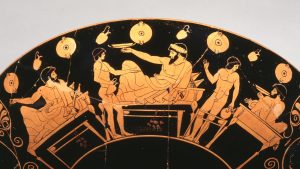

As a marker of masculinity and maturity, beards were an important part of male adornment in ancient Greece. A boy’s first beard was an important moment in his life. The appearance of body hair indicated the transition from childhood into adulthood. It also marked the transition from potential beloved (eromenos) to lover (erastes). Men’s and youths’ hair and beards can be seen in Fig. 9.3.

In Aristophanes’ Thesmophoriazusae, an older man, Euripides, tries to convince a younger man, Agathon, to dress as a woman to sneak into the Thesmophoria, an all-women’s festival. Upon his refusal, Mnesilochus, Euripides’ kinsman, offers to go instead, and Euripides then proceeds to shave Mnesilochus’ face and body (Aristoph. Thes. 153-265). While Mnesilochus’ face is being shaved, he initially runs away and in line 233 refers to being beardless as “fighting without armour.” In line 239, upon seeing himself without his beard, he calls himself by a new name and says the person reflected is not him. This scene helps to show the deep connection beards had with masculinity and strength, as the process of beard removal was both a physical and emotional transformation for Mnesilochus. Adult men were expected to have beards, and it was considered an important marker of their status as citizens. In Aristophanes’ Assemblywomen, wives of citizen men disguised themselves as men by donning fake beards and their husbands’ cloaks in order to take over the assembly, a men-only political gathering (Aristoph, Eccl. 25-30). These episodes show the connection between beards and masculinity.

Styling Statues

The Caryatid Hairstyling Project took place in 2009 at Fairfield University. Its goal was to recreate the hairstyles of the caryatid statues (columns carved to resemble women on the porch of the Erechtheion) on the Athenian Acropolis (Fig. 9.4). Dr. Katherine Schwab, the project director, started by trying the styles on herself with the help of a professional hairstylist, Milexy Torres. Dr. Schwab then expanded the experiment by recreating the hairstyles on her students. They looked for students who had thick, full, and curly or wavy hair, similar to what was and is found in Greece. Each of the girls were assigned a different caryatid’s hairstyle, based on their hair type and what Dr. Schwab and Ms. Torres believed the caryatid’s hair type to be.

One goal of this project was to gain an understanding of whether the hairstyles shown on the caryatids were realistic to real hair. They concluded that these hairstyles most likely reflected the hairdos girls would wear to festivals or other big events, similar to when one gets their hair styled for a wedding or important party today. The hairstyles were complicated and brought forward questions of how ancient Greek women got their hair to stay in place and what tools they used for curling their hair. Was it an iron similar to today? Ms. Torres thinks the ancient would have used some type of wax to keep their hair in place, like a modern styling gel or hairspray. At the end of the project the students stood in the position of their caryatid, at the correct spacing for where they would be on the Erechtheion. Standing in the formation of the statues they were portraying allowed for a deeper connection with the past and the history of these hairstyles. It revealed the sociological impact of these hairstyles: how the hair was worn helped to explain who a girl and woman was and how she fit into society.

The project allowed people to connect more with the ancient world by showing that these are processes that can be recreated today. It helped shed light on the effort and care that went into these hairstyles and brought them to life.

A woman’s hairstyle was also an indicator of what stage of life she was in. Young girls would wear their hair long and loose around their shoulders, or partially up in a top knot. When girls hit puberty and were getting ready for marriage, they entered the status of parthenos (maiden). During this stage of their life, they would tie their hair back into a braid, as seen in Fig. 9.2. In this period, their hair would only be partially covered by a band, and the ends would show through.

When women got married, they became gyne (woman or wife), and they would start to wear their hair in updos, sometimes in a chignon (ponytail), or completely banded around their head similar to styles shown in Fig. 9.5. Their hair would also be bound in a sakkos, as described in chapter 10, and then covered with a small veil.

Elite, wealthy women and sexual companions (hetairai) wore similar hairstyles. This parallelism indicates that hair arrangements and styles were based more on age than on an individual’s social status. Short hair on women, however, would often indicate that an individual was enslaved. Female attendants in visual imagery, like in the stele of Hegeso (see Fig. 20.3 in chapter 20), are often shown with short hair as opposed to the long hair of the women they attend to. As in the case for men, there were also regional differences in hairstyles. In Sparta, young girls wore their hair long and loose, like in other parts of Greece. Spartan brides, however, would shave their heads on their wedding day.

Hair was also used to convey emotion. When mourning, women regularly unbound and tore at their hair as a show of grief (on mourning see chapter 15 and Fig. 15.2).

Conclusion

Hair was an important aspect of the ancient Greek world. It allowed people to understand what stage of life someone was in. Hair is a malleable piece of adornment that we all carry with us. It tells us a lot about those around us, and it was the same for the ancient Greeks, too. Hair identified people as marriageable or mature, it represented whether they were safe and happy or upset and mourning. Hair helps us understand what people are feeling and who they are, so it is always important to take a deeper look at it.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Biddle-Perry, G., and M. Harlow, eds. 2022. A Cultural History of Hair in Antiquity. Vol. 1. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Draycott, J. E. 2017. Hair Today Gone Tomorrow: Bodies of Evidence: Ancient Anatomical Votives Past, Present and Future. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

Haas, N., F. Toppe, and B. M. Henz. 2005. “Hairstyles in the Arts of Greek and Roman Antiquity.” The Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings 10.3: 298–300.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nicolson, F. W. 1891. “Greek and Roman Barbers.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 2: 41–56.

Schwab, K., and M. Rose. 2015. “Fishtail Braids and the Caryatid Hairstyling Project: Fashion Today and in Ancient Athens.” The Journal of Fashion, Beauty and Style 4.2: 1–24.

Stoner, L. B. 2017. “Hair in Archaic and Classical Greek Art: An Anthropological Approach.” Ph.D. diss., New York University, New York.