4 Fasten Your Garments: Fasteners As Tools, Accessories, and Symbolic Markers

Katie Mazurkiewicz

When you pull on a t-shirt, do you ever think about the dozens of little stitches lining your sleeves, collar, and sides? These important features of our clothing not only maintain the fabric’s shape but also ensure that it remains in place, covering our bodies and requiring little to no adjustment by the wearer while they are worn. Sewn garments were not foreign to the Greeks in antiquity but a variety of fasteners (including pins, buttons, and brooches) were used more often to hold clothing together. Though practical, fasteners were richly symbolic with considerable ties to gender, status, and even personal agency.

Fastener Types

Various types of fasteners were employed throughout the Archaic and Classical periods. The earliest type, predating 1200 BCE, was the straight pin of bronze. Resembling a knitting needle with a head or a bulb at one end acting as a stopper, it was the most dangerous of all the fastener types. They are often found preserved in funerary and religious contexts and some measure from 13cm up to 87cm, with the sharp, metal end left uncovered. By 1200 BCE, the fibula (plural fibulae), fashioned from bronze and other materials, including bone, was introduced. They are appropriately dubbed the “ancient safety pin”; their bodies differed, some more curved and elaborately designed, but the mechanism securing the sharp end of the pin parallels modern safety pins.

One fibula from Boeotia in the Archaic Period illustrates the typical crescent-moon-shaped body (here decorated with simple lines), coiled pin, and catch (Fig. 5.1).

Buttons appear less frequently than their predecessors. Introduced in the 6th century BCE, buttons were made of bronze, clay, amber, glass, and bone. There are other types of fasteners, but the ambiguity of ancient Greek terminology makes it difficult to pinpoint the exact type that is referred to. Thus, the word porpē (from peirō, meaning “to pierce”) suggests the existence of some type of garment pin and is usually translated as a brooch, clasp, or fibula. Similarly, the term peronē, while used to indicate a straight pin, has also been translated as a brooch or buckle.

Fastener Placement

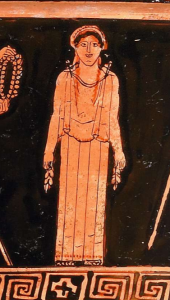

Ancient literature and material evidence, namely pottery and sculpture, help us determine where different fasteners were secured on garments. Most depictions of fasteners on pottery come from red-figure vases dating to the early to mid-5th century BCE, as shown at Pandora’s shoulders on a calyx-crater (Fig. 5.2).

In this image, Pandora wears one of the early straight pins, whose heads are down-facing (i.e., closest to her head), at each shoulder. Buttons, fibulae, and other pins are also depicted on pottery, either with one at each shoulder or multiple along each arm. Although pottery can help identify the placement of fasteners, the incised decorations are often not detailed enough to differentiate between the latter three fastener types.

Sculptures offer even less about the kinds of fasteners the Greeks used but are good indicators of where they were placed. To mimic the realistic placement of pins on garments, artisans drilled holes at the shoulders of sculptures and metal pins or fibulae were crafted to be inserted. Unfortunately, these fasteners do not survive either because they were melted down and the metal was repurposed or because they simply fell apart over time. Nonetheless, the surviving holes preserve their intended position.

Ancient literature seldom discusses fasteners and when it does, the details are vague. Since fasteners were an everyday accessory, it is possible that ancient authors felt it was not worth describing. However, some sources tell us where pins were placed. In Homer’s Iliad, Athena adorns Hera in fine clothing so that she might seduce her husband, Zeus. Hera’s garment was pinned with golden brooches at her chest (Hom. Il. 14.180). Another description comes from the Odyssey, wherein Penelope is gifted a garment adorned with twelve golden brooches pinning the fabric (Hom. Il. 18.290). In this latter scene, we can imagine six pins along each arm.

You will notice that each passage utilizes “golden brooches” to indicate the fastener types. Homer’s terminology is vague and lacks enough detail to ascertain exactly what brooches looked like, how they were pinned to the fabric, and whether they were synonymous with other fastener types. Neither the material evidence nor the literary sources are independently reliable as indicators of fastener styles, designs, or placement. Thus, research combining examples from different media brings us closer to understanding how fasteners were used.

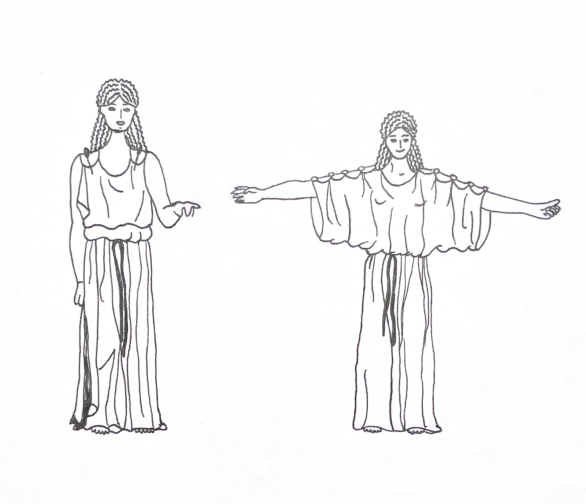

Disarming Women

In his Histories, Herodotus suggests that the transition from the long, sharp, straight pin to the fibula, buttons, or other, smaller fastener types resulted from a violent episode in Greek history. After a fatal Athenian expedition to Aegina wherein all but one man died, Athenian women were furious and killed the lone survivor in their anger with the pins fastening their clothing. After this time, they were required to adopt a style with safer fastener types (Hdt. 5.87.2-3). Fig. 5.3 differentiates these fastener types. One way to interpret this stylistic shift was men’s desire to reinstate the traditional patriarchal scheme that restricted women’s autonomy. By disarming women of “weapons” that were, by ancient standards, “unfeminine,” the Greeks reduced any threat women posed to men. For women, the change meant their ability to protect themselves was diminished.

Herodotus is not the only ancient source that recalls the danger of pins to Greek men in antiquity. In Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus, after Oedipus discovered that his mother, Jocasta, had hung herself, he removed the “golden brooches” from her garment and stabbed them into his eyes (Soph. OT. 1265-1270). Although Oedipus harms himself, his instinct to reach for the fasteners as a weapon indicates his familiarity with the danger they posed. The Trojan women of Euripides’ Hecuba were more active in the harm they brought to Polymestor, who described that he was held down by his attackers when they took the pins from their clothing to blind him (Eur. Hec. 1165-1170). If there was any truth to these ancient accounts, men recognized the danger posed to them and their dominance by women equipped with sharp pins. To restore order, women were disarmed.

Gender and Fasteners as Communicators

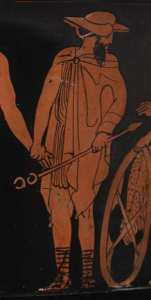

Fasteners are more commonly associated with women than men. Typically, men’s clothing was sewn, and loose ends were cast over an arm or shoulder. One exception to this was the chlamys, which Hermes is depicted donning on a red-figure kantharos from the early 5th century BCE (Fig. 5.4).

This cloak was secured at the right shoulder with one pin. Judging by the crescent-shaped body, this may be a fibula. In Book 19 of the Odyssey, Odysseus also utilizes a fastener to secure his purple cloak, which is described as an elaborate golden brooch with double pins (Hom. Od. 19.225). These examples illustrate that pins may not have been used for everyday garments but for additional layers such as cloaks. They were practical and, for particularly wealthy or renowned men like Odysseus, could be used to project a man’s status depending on their material and design.

Unlike men, women consistently wore fasteners throughout the Archaic and Classical periods, no matter the type of garment they wore. There is an interesting relationship between the types of clothing worn and fastener styles for women within these periods. The Doric peplos was paired with the straight pin, the Ionic chiton with small brooches or pins, and the Doric chiton with fibulae. Expressions of sexuality and status may explain why fasteners were consistently used among women across these changing styles. Most pin types secure the fabric at the shoulders, chest, or upper arms, close to the wearer’s face. Particularly flashy pins would have drawn the attention of others, alerting them to a woman’s wealth and status. The proximity of the accessory to the face ensured that not only was the pin noticed, but so was the wearer.

If we recall Hera’s plan to seduce Zeus, part of her allure stemmed from the utilization of golden fasteners placed at her breasts. Her standing as the wife of Zeus, god of gods, guaranteed that Aphrodite would adorn her in only the finest attire. As the goddess of sexuality, Aphrodite knew even the smallest touch, such as the pins and their placement, would ignite the desired sexual response from Zeus.

Pinning It All Together

Fasteners in Archaic and Classical Greece were more meaningful than their ordinary functions might suggest. Variations in size, material, and design could be manipulated by the wearer to communicate specific messages relating to status, wealth, and personal agency. While women are predominantly associated with fasteners, both men and women adorned themselves with pins in a unique way. For women, pins shared connotations with sexuality, attraction, and autonomy through protection. When men used fasteners, the importance of their role among others in society was heightened. Together, they could rely on fasteners to secure their clothing and represent their socioeconomic standing. Without a doubt, they were a fundamental facet of adornment in antiquity.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Alden, M. 2003. “Ancient Greek Dress.” Costume 37: 1–16.

Brøns, C. 2014. “Representation and Realities: Fibulas and Pins in Greek and Near Eastern Iconography.” In Greek and Roman Textiles and Dress: An Interdisciplinary Anthology, edited by M. Harlow and M. L. Nosch, 60–94. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tortora, P. G., and K. Eubank. 2005. Survey of Historic Costume. New York: Fairchild Publications.

Woodford, S. 1986. An Introduction to Greek Art. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.