19 Crowns and Wreaths: Resting on Their Laurels

Matthew Martins

All crowns and headdresses in ancient Greece were known as stephanos, originating from the verb stephō meaning “to put round”, which accurately describes the construction of these very Greek head ornaments.

Wreaths

As indicated by its Greek name, wreaths were made by bending leafy branches and tying them into a circle. Though we do not have any physical remains of these, there are multiple archaeological examples of gilded, gold, or silver wreaths in burials made to simulate their leafy counterparts, and these can, in some cases, aid in our understanding of how the organic ones would have looked.

This example made of gold (Fig. 18.1) shows how two branches could be held together with some sort of twine and bent to fit around the head. From as far back as there is a historical record to their conquest by Rome, the ancient Greeks wreathed themselves with a variety of branches for different occasions. Wreaths were commonplace outside of bodily adornment as well, often given as dedications at funerals or weddings (Plat. Laws 12.943c). Priests wore one whenever they carried out sacrifices at their altars, and victorious athletes were crowned with them. Orators and theatre choruses would also wear a wreath during performances, as did the elite male participants of the symposium (Plat. Sym. 212e). While the context and social status of the wearer varied greatly, the implication was always that a wreath signified that person as important.

The varietals of flora used to fashion these wreaths correlated to the event to which they were related. In the case of religious sacrifices, the wreaths were associated with the divinity to whom the event was dedicated. Zeus, for instance, was favourable to oak leaves while his daughter, Athena, preferred olive leaves. In the Panhellenic games, the four major athletic festivals of ancient Greece, the wreaths awarded to the winners were particular to the festival and the god associated with said festival: laurel branches for the games at Delphi, pine for Isthmia, wild celery for Nemea, and olive for Olympia (Luc. Anach. 9).

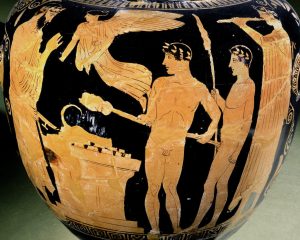

As discussed above, archaeological remains for the organic wreaths are nonexistent. Instead, we can look to artistic depictions for evidence of their use. Religious scenes were common in pottery art, like the wine mixing jar (stamnos) in Fig. 18.2, where the participants of the sacrifice are depicted wearing wreaths. The wreath was a specific headdress to be worn when actually performing a sacrifice, not just a part of the common garb of a priest, as suggested by the later “Sacred Law of Andania” from the first century CE (CGRN 222.14). In the scene depicted in this image, the older bearded man to the left of the altar holds up one hand as he pours something onto the altar from a wide, shallow sacrificial dish. The three young men on the opposite side of the altar also appear to be a part of the ritual proceedings as the two in front are holding sticks with meat skewered on the end: one is in the process of holding it over the presumably burning fire on the altar’s top, while the other is waiting for his turn to do the same. The third youth is providing the musical accompaniment. All four of these individuals are wreathed to indicate their status as ritual participants in the sacrifice.

Crowns

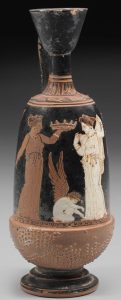

With few notable exceptions, the idea of royalty and kingship was foreign to the Greeks and thus was the association with crowns and royalty. Crowns or diadems made of gold and silver were part of the jewelry worn by elite women and commonly appear in wedding scenes as on this the oil flask (lekythos) pictured in Fig. 18.3.

In this image, the woman in white is presumably the bride as she prepares to veil herself while a winged Eros (the god of sexual desire) ties her sandals. Facing her is a woman handing her a tray. Behind her, not visible in this image, is a woman holding a necklace. All three women are adorned with diadems.

Extant remains of diadems come from a funerary context, either as a part of the deceased’s entombment costume or else as a burial good amongst other treasures. These examples were likely only made for the purpose of the burial since they are made of either too thin a sheet of metal or are far too ornate and delicate to have been practical headwear for a priest or bride.

As was the case with the vegetal wreaths, crowns came in different varieties in the Greek world. In part, this variety was due to the significance of organic wreaths to the Greeks in the ritual/festival context, as many were designed to look as though they were real leaves, as already seen. These kinds of gold and gilded wreaths begin to appear from the late classical period into the Hellenistic period, when gold was becoming a lot more common in jewelry in general (see chapter 17).

Reminders of Past Glories?

One of the more elaborate examples of these gold, leafy funeral wreaths originates from a grave at a Greek site in Southern Italy (Fig. 18.4). Known as the “Kritonios Crown” in reference to the name inscribed below the winged Nike at the crest. It is an impractical headdress were it to be made of real organic material, as it boasts a garden of leaves and flowers coming off the oak branch base. Included are simulations of roses, ivy, myrtle, convolvulus, and narcissus, even tiny grapes on vines. At the centre of the wreath, a winged female figure with an offering dish, who is crowned herself, presumably Nike, is flanked by three smaller winged figures on either side. She stands on top of a pedestal which has these words inscribed on it:“Kritonios dedicated this crown”. While the identity of the grave occupant is entirely unknown, it is significant that this “Kritonios” wanted to bury the corpse with a wreath bearing symbols of victory and featuring many of the floral types associated with athletic games. Could the dead have been a victorious athlete whom Kritonios sought to honour? What if the entombed were his wife, daughter, or sister? Might this be an example of Greek men using the women in their lives to display their wealth and status?

Bibliography and Further Reading

Christesen, P. and D. G. Kyle. 2014. A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Despini, A., E. Allamanis, and T. Xanthakis. 2006. Greek Art: Ancient Gold Jewellery. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon.

Guhl, E. K., W. D. Koner, and F. Hueffer. 1889. The Life of the Greeks and Romans Described from Antique Monuments. London: Chatto & Windus.

Jeffreys, R. A. 2022. “Gilded Wreaths from the Late Classical and Hellenistic Periods in the Greek World.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 117: 229–61.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oakley, J. H. 2020. A Guide to Scenes of Daily Life on Athenian Vases. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Oliver, A. 1966. “Greek, Roman, and Etruscan Jewelry.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 24.9: 269–84.