18 Amulets: Magic and Medicine

Lucas Pinheiro

Unplanned pregnancies, ill-health, and struggling with conception affected women in ancient Greece just like today. In the absence of advances in germ theory and detailed knowledge of female anatomy, women had few options for their health. In these situations, they turned to the magical power of amulets, which they believed promised relief and protection from their ailments. Aside from women, children also interacted with amulets in their early lives, and men had an especially complicated relationship with them.

What Exactly is an Amulet?

In ancient Greece, the intersection between ritual and medicine was always relevant. At the center of that relationship was the amulet. An amulet refers simply to an object imbued with magical power. Amulets could take on any shape and be produced from any material, ranging from bone to gold. Their exact typology is varied, with the oldest and simplest forms of amulets being an inscribed stone or a leather knot. As amulets evolved, they became increasingly concerned with symbology. The representation of a phallus on an amulet was intended to inspire fertility, while depictions of the Hellenistic deity Harpocrates had the power to protect an unborn child.

Amulets were also used to prevent or treat specific injuries or ailments, like hemorrhoids, and thus were an ancient form of alternative medicine. A more elaborate form of amulet was an incantation which was inscribed onto metal foil, rolled, and worn on the body. Amuletic incantations feature magical words of power, which can be rooted in ancient tradition or made up. Amulets are deeply concerned with ritual, and are thus items of purpose, not fashion. In some examples, amulets were even used as rain charms to encourage desired weather events.

Where Did All This Magic Come From? Amulets and Egypt

While an important part of the Greek lifestyle, amulets were influenced by Egyptian culture. Amulets had been imported from Egypt to all parts of Greece since the Bronze Age, and they appear in Egyptian culture as early as the Predynastic period (ca. 3100 BCE). By 700 BCE, rituals and deities relating to amulets were being shared across cultures. One example is an Egyptian god of birth and regeneration, Pataikos, whose amulets were found at sanctuaries of Apollo, Artemis, and Poseidon in Greece. Pataikos amulets were used to protect children, speed up recovery from injury, and safeguard against the risks of childbirth.

Naucratis, a Greek colony in Egypt, serves as both an example of a production site where amulets were made, as well as a cultural melting pot. At Naucratis, Greek and Egyptian society blended as ideas and ritual were exchanged, resulting in mass importations of Egyptian items into Greece. Many of these items were amulets, evidenced by large numbers of Pataikos amulets from Naucratis deposited around the Greek world at Paros, Eretria, Argos, Sounion, and more. In understanding the prevalence of Egyptian deities on amulets found in Greece, it can be said with certainty that Egypt greatly influenced amulet culture in the Mediterranean.

Understanding Women and Children Through Amulets

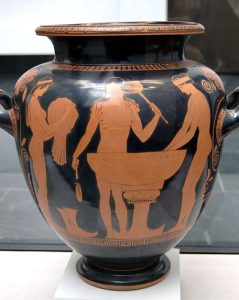

In ancient Greek society, amulets were primarily worn by women and children. A common way women wore amulets, as seen in Greek art, features the amulet tied around the thigh, such as the women depicted on the stamnos above (Fig. 19.1). Women of all backgrounds wore thigh amulets, including metics, hetairai (sex labourers), and Athenian wives. They all wore amulets around their thigh for the same purpose, to make use of their powers of fertility. Thigh amulets were believed to be imbued with the power to promote or prevent childbirth, and to safeguard against the spread of disease.

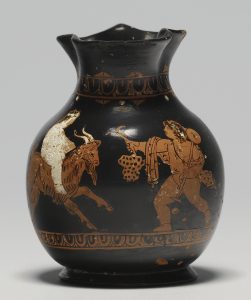

Children and infants are also depicted wearing amulets, using their magical power to protect them in their most vulnerable stage of life. Children also wear amulets under specific ritual conditions, such as the Athenian Anthesteria festival. Consider this red-figure wine jug (choes) with an image of boys celebrating at this festival (Fig. 19.2). The older boy on the right wears a string of amulets around his neck. In this festival dress, the boy wears his infancy amulets for the final time, as he transitions to the status of a youth in society. These amulets were foiled and rolled into amulet casings, such as this gold example in Fig. 19.3. Of all the infants depicted in scenes at the Anthesteria festival, 98% of them are wearing amulet strings. From this statistic, the significance of amulets in youth culture becomes apparent.

Amulets and Men: A Tense Relationship

Men are frequently omitted in amulet scenes and seem to have a complicated relationship with amulet culture. In Aristophanes’ Wealth, a “Just man” brandishes an amuletic ring in a protective context and is mocked, then dismissed (Aristoph. Pl. 883). In the Women at the Thesmophoria, the women of Athens discover their husbands are using a new kind of magical protection separate from the amulets they used to buy for them, possibly referencing amulet casings like Fig. 19.3 (Aristoph. Thes. 421-28). In Plutarch’s Pericles, one of the signs of Pericles losing his senses comes from him suddenly believing in amulets and other similar forms of magic (Plut. Per. 38.2). Men, however, did use amulets. Male graves in the Kerameikos cemetery in Athens include amulets, and specific amuletic medicine existed for men, especially relating to issues concerning male genitalia. A papyrus text from Egypt includes a medicinal incantation for inscribing on an amulet designed to treat the recurring nosebleeds of a young adult man. Despite this material evidence of men’s use of amulets, the primary sources suggest the existence of a stigma for any man who embraced them publicly. In this way, men demonstrate an anxiety with amulet culture, which explains why they are not shown with them in Greek art.

So What Can We Learn From Amulets?

When considering amulets, it is important to view them as a type of adornment distinct from other forms of accessories. Amulets had a specific purpose in mind with their creation and use. The position of the amulet on the body and the use of magical incantations were not for the sake of appearances, but to accomplish a goal with magical assistance. The intended use of an amulet varies across typologies and wearers. Sometimes it can be challenging to identify the exact use. Men, women, and children in Greek society all interacted with amulet culture, but their use and attitudes towards amulets varied. They represented a significant part of women’s health culture and were an essential part of their daily lives. Amulets were worn ritually at festivals by young boys, marking a point in their lives when they could cast off their magic protection. Even men, with mixed feelings concerning amulets, considered them and chose whether to value them or not. Amulets were the manifestation of magical power in Greece, and everyone in society made use of them.

Bibliography and Further Readings

Apostola, E. 2019. “The Multiple Connotations of Pataikos Amulets in the Aegean.” Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 48: 53–66.

Castor, A. Q. 2006. “Protecting Athena’s Children: Amulets in Classical Athens.” In Common Ground: Archaeology, Art, Science, and Humanities. Proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Classical Archaeology, Boston, August 23–26, 2003, edited by C. C. Mattusch, A. A. Donohue, and A. Brauer, 625–27. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Faraone, C. A. 2011. “Magical and Medical Approaches to the Wandering Womb in the Ancient Greek World.” Classical Antiquity 30: 1–32.

Goodison, L. 1989. Death, Women and the Sun: Symbolism of Regeneration in Early Aegean Religion. Bulletin Supplement 53. London: University of London, Institute of Classical Studies.