16 Piercing and Its Perception in Ancient Greece

C-Allan Watson

Piercings are a common form of body modification around the world, with many cultures practicing varying levels of piercing body modifications from small studs in the ears to spacers placed within the cheeks. In the archaic and classical periods of the ancient Greek world, ear piercing was common among women, with Greek men shaming other males who had such piercings and connecting earrings on men with foreigners. There was thus a highly gendered perception of piercing: women were expected to have them, while men were not. What influenced these perceptions of piercings and whether or not they were always followed will be explored in this chapter.

The visual and archaeological evidence for piercing in the Greek world points to ear piercing. The practice dates to Bronze Age cultures like the Mycenaeans and Minoans. There is also evidence for the practice in the early Iron Age. Burials from Lefkandi, on the island of Euboea, have yielded earrings made of gold, some of which date back to the tenth century BCE. In addition to burials, earrings have been found at sanctuaries as offerings. Representations in sculpture and scenes on Greek pottery also show that earrings were a popular form of adornment and thus ear piercing was common, at least among women.

The Greek Male

In his Anabasis, Xenophon says, “For that matter, this fellow has nothing to do either with Boeotia or with any part of Greece at all, for I have noticed that he has both his ears bored, like a Lydian’s” (Xen. An. 3.1.31). In the passage, Xenophon emphasizes the view that men with earrings are non-Greek, and for a Greek man to have them is insulting to the Greek image. In this case, bored ears, that is, pierced ears, mark the man as Lydian, instead of Greek. The Lydians were a distinct culture located in western Anatolia, modern Türkiye, known for their coinage, language, and myths. Lydians were regarded as effeminate by the Greeks because of their luxurious lifestyle and dress. Such associations indicate the aberration of a Greek male having his ears pierced. It also highlights the fact that the Greeks were used to seeing men from different cultures with their ears pierced, such as the Lydians, but other cultures, like the Persians, also had body piercings. An example of non-Greeks can be seen in Fig. 16.1, where a mounted horseman in lavish dress and with pierced ears is stabbing at a Greek on the ground with his shield up.

The transition between the Greek archaic period (8th-6th centuries BCE) to the Greek classical period had an influence on perceptions of piercing for men, partially due to the Persians’ attempted conquest at the beginning of the fifth century BCE when the Persians succeeded in demolishing Archaic Athens, leaving many of the temples in ruin. The destruction of Athens led the Greeks to reject anything associated with or resembling the Persians, including the Persian practice of men piercing their ears, although there were slight exceptions when it came to the symposium (discussed below).

The Greek Female

Compared to Greek men, Greek women were expected to have pierced ears for earrings, and it was a part of the women’s erotic appeal. Looking at the way goddesses are depicted in Greek mythology provides some insight into attitudes towards earrings and women. For example, in the Hymn to Aphrodite, it mentions that “in her pierced ears they hung ornaments of orichalc and precious gold ” (HH 6.6-10). Aphrodite is the Greek goddess of love and beauty, but she is more associated with sexual desire and eroticism, so earrings would highlight her beauty and desirability as a sexual partner. Hera is mentioned in the Iliad as wearing earrings with three mulberry drops only when she seduces her husband, Zeus (Hom. Il. 14.180-1). Both goddesses are depicted with earrings, but they are in different contexts. Aphrodite was born of the sea and immediately had earrings to accentuate her erotic nature, while Hera used them only on special occasions for her husband. The two depictions highlight the expectations for the different classes of women. The depiction of Hera is the epitome of the Greek elite woman, only using her beauty with regards to her husband and only on special occasions. But the depiction of Aphrodite is more closely related to hetairai and pornai, the companions and prostitutes who were part of the symposium, see Fig 16.3 . While the elite woman was expected to be chaste and a fixture of the household, the hetaira was constantly advertising her beauty in the hopes of attracting clients. Her adornment included wearing earrings even when she was in the nude.

The Anacreontic Vases and a Case of Male Pseudo-earrings

The one exception to men wearing earrings is at the symposium, the drinking party where men would use parasols and wear head coverings with fake earrings hanging from them, simulating pierced ears (Fig. 16.3). There is a lot of speculation on what these vase types are depicting: some scholars believe that the men are alluding to women because of the headdress and use of the parasols and allusion of earrings; others believe that it was meant as a form of mockery of the Persian elite who were known to bring servants with parasols to shade them, wear rich elegant clothes, and to have earrings. Another idea is that it had to do with Dionysiac rituals. In this interpretation, the men mimic the effeminate nature of Dionysus and his mind-altering effects due to wine. When it comes to cults in the ancient world, it is difficult to determine what went on because of how secret they were, but known aspects of worship provided freedom from conforming to certain social norms, including crossdressing. Worshipers of Dionysus were seen as a problem for some elites throughout the archaic to Christian periods, where many elites would attempt to regulate the cults. This response was because his cult allowed followers to challenge social norms: Greek women had the freedom to get out of the house and have fun, and men could act more effeminate.

Jewelry and Speculation

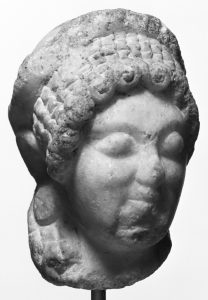

Earrings came in a lot of different shapes and sizes. Some of the earliest types found were simple spirals made from a single thin wire and bent to form the spiral. Over time, more complex shapes appeared, such as boat-shaped earrings, pyramid-shaped ones, and ones resembling pomegranates. Each sort has earring closures that pass through the earlobe. Another earring type that may have been worn was spacers. Friedrich Brien suggests that round disk-like objects typically labelled as buttons by other scholars may in fact be spacers that stretched out the earlobes. He argues for spacers based on korai (female marble statues of young women) that have wide discs positioned at the earlobes (Fig. 16.4). He suggests that their position and size made them hard to hang from the ears. For more on earrings and how they are made, see chapter 17.

Because earrings were part of a woman’s world, and most written works from the ancient Greeks come from an elite male perspective, the question of when and how the ears were pierced is difficult. There is evidence for ear piercing in an account attributed to Aristotle, which states, “Why does the left ear heal more quickly, as a general rule, when it has been pierced?” ([Arist.] Pr. 961a). Aristotle notes the piercing of ears, but he does not answer how it was done, and scholars are still not sure how the piercing was carried out. One possibility is that the piercing, as a female practice, was done within the home, possibly using a fibula, an ancient style of bobby pin, which was easily at hand.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Castor, A. Q. 1999. “Enotia: The Contexts of Greek Earrings, Tenth to Third Century B.C.” Ph.D. diss., Bryn Mawr College.

Castor, A. Q. 2017. “Archaic Greek Earrings: An Interim Survey.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1: 1–34.

Cosmopoulos, M. B., ed. 2003. Greek Mysteries: The Archaeology of Ancient Greek Secret Cults. Oxford: Taylor & Francis Group.

Higgins, R. 1961. Greek and Roman Jewellery. London: Methuen.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, M. C. 1999. “Reexamining Transvestism in Archaic and Classical Athens: The Zewadski Stamnos.” American Journal of Archaeology 103.2: 223–53.

Miller, M. C. 1997. Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century B.C.: A Study in Cultural Receptivity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Neils, J., J. H. Oakley, K. Hart, L. A. Beaumont, and Hood Museum of Art. 2003. Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past. New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire.

Price, S. D. “Anacreontic Vases Reconsidered.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 31.2: 133–75.