2 Textiles in Motion: Production, Social Identity, and Dyes

Connor O'Rourke

In pop culture, we picture Greeks draped in chitons, peploi, and himations, although statues and vase paintings show they could impress without them. Yet textiles reveal what nudity does not: status, economic power, and the unseen labour behind fabric production. More than clothing, textiles wove together Greek labour, social identity, class distinctions, gendered work, and Mediterranean networks. From luxurious elite fabrics to the daily grueling task of weaving, textile production threaded through every layer of Ancient Greek society.

Textile Production, Trade, and Social Meaning

Wool was the most common textile material across all levels of Ancient Greek society. Its widespread use was supported by the abundance of sheep and the domestic, kin-based labour often performed by women, children, and enslaved people that sustained its production. Dr. Agata Ulanowska and Mrs. Aleksandra Frączek, in the Faculty of Archaeology at the University of Warsaw, use experimental archaeology in this video to demonstrate weaving on an upright loom, the most common method employed by women in ancient Greek households. In addition to household manufacture, large-scale workshops also produced wool garments for wider distribution.

The affordability and availability of wool contributed to its ubiquity, from daily wear to elite display. Traces of pigment on the Acropolis Korai statues suggest that these figures were originally depicted in brightly coloured wool garments. Scholars, including Mireille Lee, support this interpretation because wool retains dye more effectively than linen, which is more porous and less colourfast. The Korai statues underscore wool’s importance in Greek dress, evoking its thread from the lowest ranks of society to the heights of the Acropolis.

Beyond its practical use, wool carried a symbolic weight in Athenian society. In Lysistrata, Aristophanes uses the gathering and weaving of wool as a metaphor for governance. Lysistrata argues that just as tangled wool must be spun into a robust fabric, so too must Athens be unified and woven tightly for the common good (Ar. Lys. 574–94).

While wool served as the staple fabric of daily life, luxury textiles were typically reserved for elites and likely limited to special occasions. The most complete surviving examples are preserved in elite burials, where favourable conditions aided their preservation. These include finely worked wool, cotton–flax blends, and possibly imported silk, although evidence for silk in pre-Hellenistic Greece is tenuous. Linen was the most accessible of the elite fabrics. It was lighter and more breathable than wool and was primarily imported from Egypt, making it costly to own.

The Kerameikos cemetery in Athens has yielded the largest wealth of fragmented textiles, mainly composed of cotton–flax fibres. Some of these preserve intricate weaving patterns, while others retain traces of dye pigmentation, reflecting the vibrancy of Greek textiles even in fragmentary form. However, the most elaborate surviving textile was discovered in a funerary context at Koropi, Attica (Fig. 2.1). It features a diaper pattern and is embroidered with silver-gilded lions, suggesting that the textile was likely of Persian origin. The Koropi textile underscores the role of fabric in signalling status and social identity, even in death.

Gender, Class, and the Economics of Textile Production

In Athenian society, weaving was more than a domestic task; it was a symbol of feminine virtue, order, and elite identity. In Homeric literature, weaving embodied the moral excellence expected of elite women. In the Odyssey, Penelope’s weaving and unweaving of a burial shroud reflects her fidelity and domestic control (Hom. Od. 24.120–30). Similarly, on the Leukothea Grave Stele, a woman is shown with a wool basket (kalathos), a visual marker of her domestic authority and the enduring association between women, household labour, and textile production.

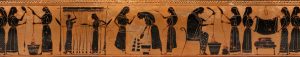

Weaving also played a vital role in the symbolic economy of the household. The Amasis Lekythos (Fig. 2.2), depicting a domestic weaving scene, has been interpreted by John Oakley as a representation of household balance and harmony, reinforced through its symmetrical composition. Woven goods were essential to a woman’s role, serving as dowries, divorce assets, and markers of household contribution. The Gortyn Law Code from Crete even granted women the right to retain half the textiles they produced during marriage in the event of divorce.

Control over textile labour was stratified by class. In Xenophon’s Oikonomikos, the management of weaving is framed as a core duty of elite women, who supervised enslaved and lower-status labourers responsible for garment production (Xen. Ec. 7.36–41). This model highlights elite women’s administrative role in household economies while distancing them from the physical labour itself.

While citizen women’s weaving reinforced household values, enslaved women were central to both domestic and large-scale commercial textile production. At the height of Athens’ prosperity, between 35,000 and 40,000 enslaved women worked in textile-related labour (Dem. 57.45). Unlike citizen women, they had no control over their work, from spinning and weaving to fibre harvesting, and were deeply embedded within exploitative economic systems.

Vase paintings include depictions of nude women with spinning tools accompanied by men carrying moneybags, suggesting that some hetairai (sex workers) engaged in weaving. The discovery of hundreds of spindle whorls at a suspected brothel in the Kerameikos further supports this association between textile production and sex work.

Foreign women and freedwomen also wove for survival. Andria, a metic (non-citizen resident), made wool cloth for a living, illustrating how textile work could provide financial independence for marginalized women. Of 57 freedwomen with documented occupations in the Attic Stelai inscription, 44 were involved in textile production, likely carrying over skills from their time in enslavement. Widows, too, spun and wove to support themselves, as seen in the Iliad, where a widow spins wool to clothe her children (Hom. Il. 12.433–35).

Together, these examples show how textile production was deeply embedded in the structures of gender, class, and labour in Athens, functioning as both a symbol of elite femininity and a tool of survival for marginalized women.

Murex Dyes, Status, and Ritual in Ancient Greece

Purple dyes (extracted from the mollusk murex) were not only expensive to produce but also symbolized status and ritual significance in ancient Greece. In certain ritual contexts, visitors were forbidden from wearing purple to prevent ostentatious displays of wealth at sanctuaries where communal equality was expected. At the sanctuary of Andania, however, cult officials may have worn purple to honour the gods. This contrast suggests that such restrictions were intended for lay visitors, reinforcing the association of purple with elite authority and divine proximity.

Purple was closely tied to elite women in both myth and reality. In the Iliad, Helen weaves a double-fold purple tapestry depicting the Trojan War, illustrating how purple dyes signified prestige, legend, and historical memory (Hom. Il. 3.125-129). Sappho describes Andromache as a bride wearing a “purple overdress” or “purple robes,” highlighting a symbolic link between purple and marriage, though no extant garments survive to confirm this practice (Sappho fr. 44 lines 8-9).

Murex dyes also appeared in funerary rituals. In Fig. 2.3, a male visitor stands at a grave, cloaked in a deep reddish-purple garment. Although the reverse side of the lekythos is not available and may have depicted a female mourner, this particular example is included to highlight the rich hue of purple still visible on the cloak. The image underscores how colour alone, even in a single preserved frame of a larger narrative, could convey ritual significance and have visual impact in the commemorative sphere of the fifth century BCE.

Purple was worn by high-ranking men as well, including military leaders, politicians, and royalty. Agamemnon was said to have walked on purple soles (Aesch. Ag. 944). In Herodotus’ Histories, the Phoenician envoy Pythagoras dons a purple cloak before addressing the Spartan assembly, a colour meant to command attention and signal authority (Hdt. 1.152.1). In the Odyssey, Odysseus receives a purple wool mantle, signifying his return to heroic status (Hom. Od. 19.226).

Dyes of Prestige and Everyday Life

Dyeing garments was a key method of expressing status and identity in ancient Greece. While some fabrics retained their natural wool or linen shades, many were dyed with plant- and animal-based substances, producing colours that ranged from soft earth tones to vibrant, labour-intensive hues. The methods, materials, and colours used often reflected both the availability of resources and the wearer’s social standing.

Plant-based dyes were the most accessible and commonly used. Some, made from ingredients such as onion skins, chamomile, and pomegranate rinds, could be prepared domestically and produced yellow, brown, and reddish hues. These were affordable to non-elite households. More intensive dyes were valued for their brightness and cultural associations. Saffron, closely associated with women’s garments, produced a vivid golden-yellow. Young girls serving Artemis at Brauron wore saffron-dyed robes (krokotoi), and the ceremonial peplos for Athena at the Panathenaea festival was also dyed with saffron.

Other plant-based dyes included madder root for deep red, woad for blue, and oak galls for black and brown. Orchil lichen yielded pink to blue tones, while alkanet produced a red pigment used both in textiles and cosmetics.

Animal-based dyes were rarer and more prestigious due to their cost and complexity. Theophrastus describes kermes, a red dye made from insects living on kermes oak trees, as highly valued for its vivid colour in high-status garments (Theophr. Caus. pl. 3.16). The Greek word for red (kokkinos) derives from these insects. Murex dyes, including the famed Tyrian purple, produced rich red-purple shades. Extracting even a small amount of dye required tens of thousands of sea snails, making it one of the most expensive and symbolically powerful dyes in antiquity.

This video by Mohamed Ghassen Nouira in Tunisia demonstrates the labour-intensive process of producing murex dye, helping to explain why it became so strongly associated with wealth and prestige.

Weaving It All Together

Textile production in ancient Greece was more than a craft; it was a force that shaped the economy, social structure, and personal identity. From the labour of enslaved women to the luxury of elite fabrics, textiles reinforced class divisions, gender roles, and economic inequality. Weaving signified domestic virtue, marriage, ritual, and mourning, while dyes like saffron and murex conveyed wealth and meaning across both life and death. Whether a daily necessity or a symbol of authority, textiles were woven into the very fabric of Greek society.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Fischer, M. 2013. “Ancient Greek Prostitutes and the Textile Industry in Attic Vase-Painting ca. 550–450 B.C.E.” Classical World 106.2: 219–59.

Foxhall, L. 2023. “Women’s Work? Who Made Textiles in the Ancient Greek World?” In Politeia and Koinōnia: Studies in Ancient Greek History in Honour of Josine Blok, edited by V. Pirenne-Delforge, M. Węcowski, and J. Blok, 253–77. Mnemosyne Supplements 471. Leiden–Boston: Brill.

Gilby, D. 2021. “Weaving the Body Politic: The Role of Textile Production in Athenian Democracy as Expressed by the Function of and Imagery on the epinetron.” Athens Journal of History 7.3: 185–202.

Lee, M. M. 2015. Body, Dress, and Identity in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, D. M. 2021. “Labor and Employment.” In The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Athens, edited by J. Neils and D. K. Rogers, 217–30. Cambridge Companions to the Ancient World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, S. 2013. The Athenian Woman: An Iconographic Handbook. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Myburgh, B. 2020. “Re-Weaving the Textile in Ancient Greece.” Intaglio 2: 52–71.

Oakley, J. H. 2020. A Guide to Scenes of Daily Life on Athenian Vases. Wisconsin Studies in Classics. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Vester, C. 2017. “Women and the Greek Household.” In Themes in Greek Society and Culture: An Introduction to Ancient Greece, edited by C. Vester and A. Glazebrook, 291–312. Oxford: Oxford University Press.