5 Policies and Privacy Legislation

Heather Leatham

This chapter will assist students to be able to:

- Understand and explain how the concept of privacy evolved to the present day.

- Understand the strengths, weaknesses and gaps of the digital privacy policies in this chapter.

In this chapter, you will explore the evolution of privacy from common to international law and examine specific legislation that arose to protect the data that a digital world captures in increasing amounts. We’ll also explore critical elements of Policies and Privacy Legislation as they relate to digital privacy broadly and in the context of education specifically, along with the relationships and gaps in the present North American policies. Further, the chapter affords opportunities to examine shared definitions and policies in Canada, the United States (U.S.), and Europe.

Privacy as a notion and ultimately a concept requiring protection has long historical roots within European/Western law. By the 1970s, with the rise of smaller and more affordable home computers, the notion of privacy began to include protection in the new and expanding digital world that fits in the palm of our hand. Gülsoy (2015) describes digital privacy as “the right to privacy of users of digital media” (p. 338), which as a definition is broad. Jennifer Stoddart (2011), the former Privacy Commissioner of Canada, emphasized that as social media sites collect data, they have obligations only to collect what is necessary. Indeed, there is also an onus to inform the user of the intended data usage so that the consumer can make an informed decision (Stoddart, 2011). When a person decides to give access to their information, whether a person or an organization, they infer that their privacy will be protected just as it would be in a bricks-and-mortar operation (Robertson et al., 2019). In examining the policies and legislations that govern what can be collected and used, a better understanding of the current state of digital privacy in education emerges.

A Short History of Privacy

We can trace our understanding of privacy as a concept as far back as ancient Greek philosophy and through its modernization rooted in British Common Law (Holvast, 2009). Common examples include new technologies and personal letters, a protected asset against unwanted readers (Holvast, 2009). In North America, as early as the 15th century, New England colonists became compelled to enhance their personal privacy with the rise of instantaneous photography and the printing press. Indeed, the fancy new technologies likely inspired Warren and Brandeis’s (1890) oft-cited and influential text The Right to Privacy (which helped shape US privacy legislation) in response to increased public access to officials’ private lives.

Shortly after World War II, privacy legislation began noticeably expanding internationally. Two examples include Article 12 in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948) and Article 8 in the initial European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (European Court of Human Rights, 2021). The articles are outlined in Figure 1 and are broad in scope but brief.

Figure 1

Articles

Article 8, Right to respect for private and family life

Article 12 No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks. (United Nations General Assembly, 1948) |

Accompanying the rise of computers, we see the next generation of privacy legislation, starting in the Germany State of Hesse and the 1971 Data Protection Act, followed by Sweden’s 1973 Data Act (Holvast, 2009). The United States then contributed four pieces of legislation within 14 years. Later in this chapter, we will look at the 1974 Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), the 1998 Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), and the 2021 K-12 Cybersecurity Act. In Canada, privacy became nationally entrenched in 1982 with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Privacy Act of 1985, and more recently the 2000 Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). At the provincial level, most provinces have their own versions based on the 1990 Freedom of Information and Privacy Act (FIPPA), while at the third level of government, there is the 1990 Municipal Freedom of Information and Privacy Act (MFIPPA). All of which govern the collection and use of personally identifiable information (PII) through various government agencies.

Insights

- Sweden’s Data Act is the first national legislation in the world on the topic.

- What is PII?: “Any representation of information that permits the identity of an individual to whom the information applies to be reasonably inferred by either direct or indirect means” (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d., para. 1).

Building on the initial efforts, digital privacy has emerged as a realm of focus to sustain and uphold human rights such as freedom of expression (Ben-Hassine, 2021). The most recent and internationally enforced privacy legislation is from the European Union, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which has global implications. Businesses in other countries must adhere to the GDPR in order to conduct business with the European Union. Specifically in the context of collecting personal data and the new notion of the right to be forgotten which first appeared in 2014 after an EU Court of Justice decision.

An Introduction to Government Privacy Acts

Privacy in Canada

As mentioned above, Canada’s privacy legislation is primarily governed by the Privacy Act (c.P-21, 1985) and PIPEDA (2000). More recently is the Digital Privacy Act (c.32, 2015) which along with PIPEDA, governs activities related to private sector business and commercial activity.

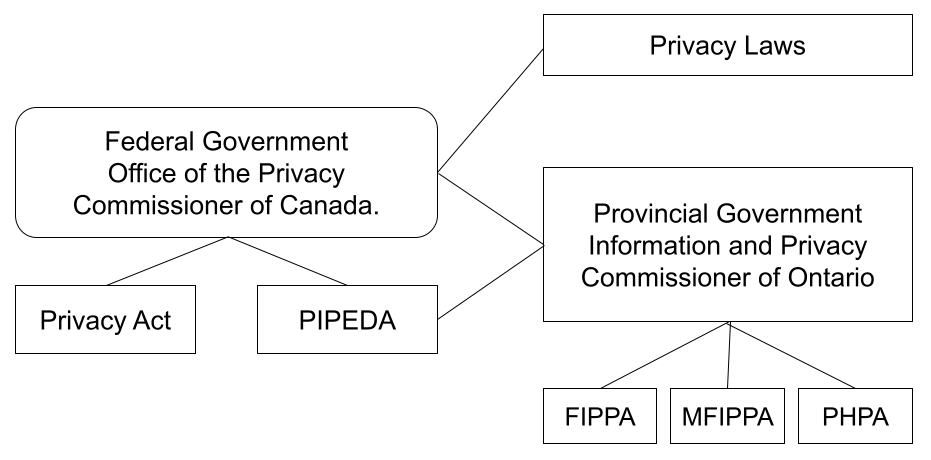

Figure 2

Privacy legislation in Canada

Note. Privacy legislation in Canada, by H. Leatham, 2017.

None of the three aforementioned pieces of legislation are specific to education and minors (though MFIPPA governs education), a point that the Privacy Commissioner of Canada stated in a 2012 decision regarding the digital application Nexopia which was marketed primarily to the youth market.

Other privacy legislation occurs at the provincial/territorial level, of which the legislation from Ontario is used for the purposes of this chapter. There are two pieces of legislation in Ontario: FIPPA (c.F.31, 1990) and MFIPPA (1990) which govern the collection and use of personally identifiable information (PII), as well as defining what PII entails. Section 28 of MFIPPA defines PII and is outlined in Figure 3.

There have been some updates to Canadian legislation since the passing of the GDPR. According to the federal Privacy Commissioner, “Quebec tabled Bill 64 that would overhaul its private sector privacy law, B.C. announced the creation of a special committee to review its equivalent law, and in November, the federal government tabled the Digital Charter Implementation Act, 2020 as part of long-awaited PIPEDA reform” (Office of the Privacy Commissioner, 2020, p. 8). These are promising pieces of legislation though they still are aimed at commercial businesses for the most part.

Privacy in the United States

The United States recognized earlier than other countries the need to protect PII as it relates to minors starting with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA, 1974). Even though computers at the time and digital records were not commonly being used, the collection of student data was still happening. Now that much of the student information, from registration to assessment, is digital, FERPA continues to be applicable, as only the data collection methods have changed. Interestingly, FERPA allows for the disclosure of PII “to organizations conducting studies for, or on behalf of, the school, in order to: a) develop, validate, or administer predictive tests; (b) administer student aid programs; or (c) improve instruction” (sec. 99.31(a)(6)). With more instruction and classroom assessments using digital tools, if a school district has a contract with a company, Google for example, then the company has access to the metadata produced by students whenever they are using the digital tools, including PII (Privacy Technical Assistance Center, 2014).

FERPA has four exceptions to the disclosure of PII that are applicable to online tools (see sec. 99.31(a)(1)(i)). In order for the exception around being a provider to be valid, the onus is on the school or the district to determine if the provider is a legitimate educational interest. In some cases, the terms of service form from the provider may encompass all the legal requirements the provider must and will be following (Leatham, 2017).

Between 1984 and 1997, there was a large increase in computer usage both at home and at school in the United States. US households with home computers jumped from 8.2% in 1984 to 36.6% in 1997 (Infoplease, n.d.), with Infoplease (2017) reporting that there were 63.5 students for every one computer in public schools during the 1984-85 school year. However, the ratio changed to 6.3 students for every computer by the 1997-98 school year (Infoplease, 2017), representing a ten-fold increase in the computer to student ratio over 13 years. With this increase of computer availability and prevalence in both education and home settings, the US passed the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA, 1998). COPPA specifically addresses the online privacy of children under 13 years of age, and it requires parents/guardians to give their consent to the use of both websites and digital applications.

The GDPR also has an age requirement under Article 6 but as of 16 years (GDPR, 2016), while Canada has no age specification in any privacy laws. According to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), COPPA “imposes certain requirements on operators of websites or online services directed to children under 13 years of age, and on operators of other websites or online services that have actual knowledge that they are collecting personal information online from a child under 13 years of age” (FTC, Part 312, 1998). COPPA requires companies to follow five specific rules in order to comply. As mentioned above, this includes:

- obtaining parental consent,

- posting a privacy policy,

- having a notice for parents,

- protecting the integrity of the collected PII, and

- allowing parents to review, revoke consent and delete their child’s information (COPPA, sec. 312.6).

The newest American law, the K-12 Cybersecurity Act (2021) requires a study of cybersecurity risks specific to schools and school districts. The law focuses on student and staff records and a review of the information systems owned, leased, or relied upon using guidelines created by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. The results of the studies will be published on the Department of Homeland Security’s website and be completed within a short time frame of 120 days from the enactment of the Act. President Biden (2021), in signing the Act into law, remarked that it “highlights the significance of protecting the sensitive information maintained by schools across the country,” and “is an important step forward to meeting the continuing threat posed by criminals, malicious actors, and adversaries in cyberspace” (para 2).

Privacy in the European Union

Though there were privacy laws enacted in the 1970s in Europe, it was not until 1995 that a pan-European law was enacted, the European Data Protection Directive to protect the privacy of all EU citizens. After its publication, member states were to create their own laws to comply with the minimum of data protection it outlined (Wolford, n.d.). In 2016, an update was established when the EU decided “to harmonize data privacy laws across Europe” (Wolford, n.d.) and passed the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) which came into force in all EU countries in May 2018. The reason this law is mentioned here is that the legislation applies to any data of a European citizen whether that data is collected within Europe or not. Article 3 states, “This Regulation applies to the processing of personal data in the context of the activities of an establishment of a controller or a processor in the Union, regardless of whether the processing takes place in the Union or not” (GDPR, 2016). As a result, all companies outside of Europe have to comply with the GDPR and amend their privacy practices in order to continue doing business within the EU. Though not specific to education, the GDPR contains an age provision as mentioned earlier in this chapter. The reality that digital apps in other countries must comply is protection for students’ PII.

The Challenge of Defining PII

PII, or Personal Data in other regions, is currently a pervasive concept but lacks a unified definition (Parkinson, 2018). While some identifiers overlap in the four Acts such as age, geolocation, health, and phone numbers, the only one that is common is name. Even using the term identifier poses challenges as Acts such as GDPR offer vague insights while FERPA moves to include scaffolded insights that include indirect identifiers. Further, some terms have multiple meanings, such as the concept of personal self in digital environments (Parkinson et al., 2017). As a result, the globally interconnected but unique Acts foster disconnects and miscommunication as different parties may interpret information differently simply by following their localized guidelines.

Canadian Policy Gaps and Education

Building on the broad approaches to PII within North America and the European Union outlined above, I propose that it is critical to increase our focus on educational environments, specifically K-12-aged students in Canada. Pal (2010) defines public policy as “a course of action or inaction chosen by public authorities to address a given problem or interrelated set of problems” (p.35). However, public policy “is made in response to some sort of problem that requires attention” (Birkland, 2014, p. 8). The GDPR is currently a strong example of an actionable and focused response to diverse problems across the European Union, especially as it can extend into the digital classroom more readily.

The obvious Canadian policy gaps in the protection of student PII have been previously noted in Chapter 2. Still, the lack of digital privacy protection for minors within Ontario and Canada is worrisome. As the COVID pandemic shift to online learning has increased the use of digital platforms, decision-makers are seeking guidance on best-practice for online platforms in the context of the current privacy laws. Yet, the lack of guidance for school boards in this digital strategy continues to put the onus on individual boards and districts to develop scattered strategies instead of building on one cohesive, provincial-wide approach. Updating the MFIPPA to include a digital landscape could be a strong starting point, at the very least.

Hopefully, we will be afforded an opportunity to make some progress shortly, as the Privacy Commissioner of Ontario (OPC, 2020) has stated an intent to,

Flesh out more details of its digital and data strategy Building a Digital Ontario, which includes plans to accelerate open data initiatives, create a new provincial data authority, and develop an online portal and other educational guidance on online data rights. (p. 11)

References

Ben-Hassine, W. (2021, December 18). Government policy for the internet must be rights-based and user-centred. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/government-policy-internet-must-be-rights-based-and-user-centred

Biden, J. (2021, October 08). Statement of President Joe Biden on signing the K-12 cybersecurity act into law. The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/10/08/statement-of-president-joe-biden-on-signing-the-k-12-cybersecurity-act-into-law/

Birkland, T. A. (2011). An introduction to the policy process: Theories, concepts, and models of public policy making (3rd ed.). M.E. Sharpe.

Equality and Human Rights Commission. (2021, June 24). Article 8: Respect for your private and family life. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/human-rights-act/article-8-respect-your-private-and-family-life

European Court of Human Rights. (2021, August). European convention on human rights: A living instrument. Council of Europe. https://echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_Instrument_ENG.pdf

FDR Presidential Library & Museum. (2018, June 06). Eleanor Roosevelt holding poster of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1949 [Photograph]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/fdrlibrary/27758131387/

Federal Ministry of Justice. (2019). Federal Data Protection Act of 30 June 2017. (Federal Law Gazette I p. 2097), as last amended by Article 12 of the Act of 20 November 2019 (Federal Law Gazette I, p. 1626). https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_bdsg/englisch_bdsg.html

f 30 June 2017 (Federal Law Gazette I p. 2097), as last amended by Article 12 of the Act of 20 November 2019 (Federal Law Gazette I, p. 1626). https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_bdsg/

Gülsoy, T. Y. (2015). Advertising ethics in the social media age. In N. Taşkıran, & R. Yılmaz (Eds.), Handbook of research on effective advertising strategies in the social media age (pp. 321-338). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-8125-5.ch018

Holvast, J. (2009). History of privacy. In V. Matyáš, S. Fischer-Hübner, D. Cvrček, & P. Švenda (Eds.), The future of identity in the information society. privacy and identity 2008. IFIP advances in information and communication technology, 298 (pp. 13-42). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03315-5_2

Infoplease. (n.d.). U.S. Households with Computers and Internet Use, 1984? 2014. https://www.infoplease.com/math-science/computers-internet/us-households-with-computers-and-internet-use-1984-2014

Infoplease. (2017, February 28). Computers in public schools. https://www.infoplease.com/askeds/computers-public-schools

Office of the Privacy Commissioner. (2020). A year like no other: Championing access privacy in times of uncertainty. Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ar-2020-e.pdf

Leatham, H. (2017). Digital privacy in the classroom: An analysis of the intent and realization of Ontario policy in context [Master’s dissertation, Ontario Tech University]. Mirage DSpace Repository. http://hdl.handle.net/10155/816

Pal, L. A. (2010). Beyond public policy analysis: Public issue management in turbulent times (4th ed.). Nelson Education.

Parkinson, B. (2018, April). Personal data: Definition and access [Doctoral dissertation, University of Southampton]. ePrints, University of Southampton Institutional Repository. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/427140/

Parkinson, B., Millard, D. E., O’Hara, K., & Giordano, R. (2018). The digitally extended self: A lexicological analysis of personal data. Journal of Information Science, 44(4), 552–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551517706233

Privacy Technical Assistance Center. (2014, February). Protecting student privacy while using online educational services: Requirements and best practices. U.S. Department of Education. https://tech.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Student-Privacy-and-Online-Educational-Services-February-2014.pdf

Rama. (2011, October 26). Commodore PET 2001 [Photograph]. Wikipedia Commons. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Commodore_2001_Series-IMG_0448b.jpg

Robertson, L. P., Leatham, H., Robertson, J., & Muirhead, B. (2019). Digital privacy across borders: Canadian and American perspectives. In, A. Blackburn, I. L., Chen, & R. Pfeffer (Eds.), Emerging trends in cyberethics and education (pp. 234-258). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5933-7.ch011

Spiske, M. (2017, February 14). Code on a computer monitor [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/Skf7HxARcoc

Stoddart, J. (2010). Privacy in the era of social networking: Legal obligations of social media sites. Saskatchewan Law Review, 74, Article 263. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/sasklr74&div=20&id=&page=

United Nations General Assembly. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

United States Department of Labor. (n.d.). Guidance on the protection of Personal Identifiable Information. https://www.dol.gov/general/ppii

Warren. S. D., & Brandeis, L. D. (1890). The right to privacy. Harvard Law Review, 4(5), 193-220. https://doi.org/1321160

Wolford, B. (n.d.). What is GDPR, the EU’s new data protection law?. GDPR. https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/