9 Digital Privacy Leadership

Bill Muirhead and Lorayne Robertson

New challenges for educational leaders

Addressing digital privacy within educational settings requires new skills and new leadership qualities to support learning without the risk of privacy infringements. Leaders must ensure that learning environments are managed in ways that protect student privacy and can avoid unintended risks when adopting new technologies including student information systems and student and teacher software and hardware. There is growing awareness of the responsibilities of managing privacy within learning contexts. As Nagel (2018) observes from an analysis of the Speak Up Research Project for Digital Learning, “Data privacy and security are top concerns among education IT pros. More than half of technology leaders in K-12 schools (58 percent) report their top concern with cloud applications is ensuring data privacy” (p. 34). Given this significant anxiety among school leaders regarding privacy in general and cloud computing applications in particular, there has been insufficient research and attention toward identifying what can best be called leading through privacy risk.

Within educational settings, a number of technological innovations and their growing use within schooling have accelerated, highlighting the challenges that educational leaders face in managing emerging privacy concerns. The challenges faced by educators can be broadly grouped into the following categories:

- Digitization and collection of student data, including digital permanence

- The leadership gap informed by both education and technological skill sets

- The leadership matrix

- Adoption of cloud-based applications which provide both convenience and risk

- Leadership responses to curricular gaps regarding privacy education

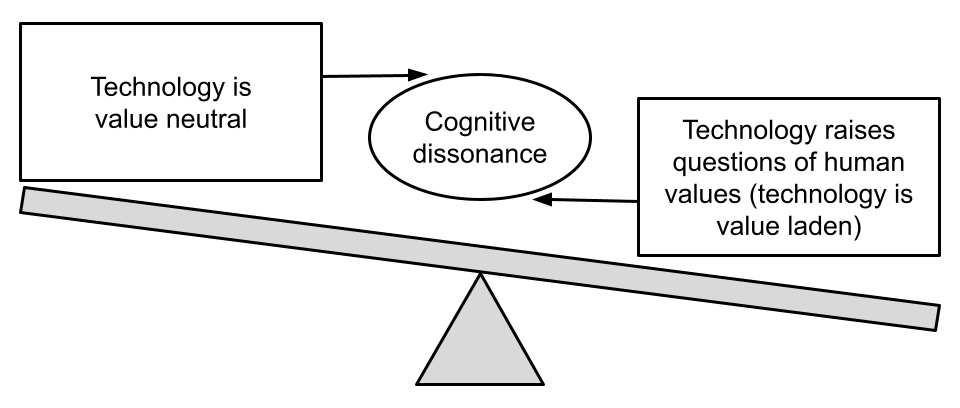

In an attempt to conceptualize how to balance convenience against protection (the privacy paradox), educational leaders are advised, as a first step, to consider their own personal and professional values that inform technological adoption and leadership actions. Rather than taking an applied view of technology as solutions in search of problems, the authors argue that educators and technology leaders must first take a step back to construct a philosophical perspective regarding the complex roles and changes to an organizational culture that technology plays within organizational operations. Leaders must also consider the potential effects that new affordances can have on learning environments. Mastering the cognitive dissonance inherent in the use of educational technologies is depicted as a fulcrum balancing technological affordances as value-neutral with values-based beliefs (Webster, 2017). Identifying one’s beliefs is a crucial first step in identifying the need for student privacy while balancing new technological capabilities. Figure 1 below from Webster (2017) highlights the intellectual work required of technology leaders to inform their actions regarding privacy.

Figure 1.

Technology is value-neutral vs. technology raises questions of human values

Identifying one’s personal beliefs about privacy is a crucial leadership step before leading systems in the use and application of student data and its potential learning benefits. Basing decisions on personal beliefs will help leaders weigh potential risks associated with data acquisition and aggregation and with institutional requirements and potential privacy implications.

Digitization and the collection of student data

Dataism is a term articulated by David Brooks in 2013 in an article from the New York Times where he described a dataism mindset that, if it could be measured it should be collected and used to quantify and inform the human experience. Quantification of the human experience through a combination of technologies that can capture, store and enable analytic tools to identify trends, and insights have been a major development in computing over the past two decades. Lupton (2021) conducted a study of Australian teachers’ understanding and practices surrounding the digitization of student data. She observed that students’ learning, physical movements and other personal details have been the subject of intensifying forms of monitoring, measuring and algorithmic processing with the use of educational technology” (p. 281). Jim Balsillie (2019), the co-founder of the Blackberry and President of Research in Motion has observed, in The Financial Post, that the present domestic and global regulatory frameworks are not designed to deal with emerging challenges such as disinformation, fake news, the toxicity of social media, the dynamics of the attention economy, and the technology’s power through the control of data. He states that “data is not the new oil-it’s the new plutonium” (Balsillie, 2019, para. 9). He further observes that data can be both powerful but when misused it can be difficult to clean up. He advocates for international coordination to manage data.

Yet, while digital student information is increasingly stored and retained over time in data sets (known as digital permanence or digital legacy), concerns regarding student privacy and digitalization of student data have grown. Unlike past practices where student information was paper-based and information about each student was kept in administrative offices or archived in school board basements in corridors filled with file boxes, the development of inexpensive computer storage and interconnected computer networks has meant that student achievement data, student personal information, teacher-generated data, student assignments and projects, test scores, specific family data including siblings, addresses, demographic data and historical data can now be both kept inexpensively and shared widely among a wide set of school personnel in a context where privacy policies are underdeveloped. While digitized student information may assist educators to better identify learning interventions or create new approaches to support learners with specific needs, widespread access to student data and the potential to misrepresent student capabilities can lead to misdirection at best and, at worst, reinforce prejudices and labelling of marginalized students. As Chapter 6 on the Privacy Paradox highlights, the ever-increasing digitalization of the human experience creates privacy issues for many and particularly students for whom consent is not given, asked for, or fully understood.

For educational leaders it is an essential task to protect student data as the digitization of student data now include:

- Student assessments

- Teacher notes

- Clinical records

- Family composition

- Family income

- Ethnicity

- School attendance

And, potentially:

- Health records

- Court records

Understanding how data is collected, aggregated, and to what purposes it is used is a crucial leadership requirement to leaders in educational settings.

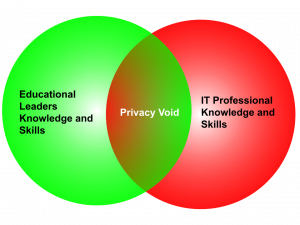

The Leadership Gap

The requirement to consider privacy within educational systems can lead to privacy avoidance where privacy policies and consequent decisions are avoided for lack of expertise or avoidance of complexity. This void often leaves front-line educators to figure it out on their own or to interpret policies without the skills or foundational knowledge. The consequence can often be, a) to avoid digital technologies or minimize their use in educational settings, b) avoid any innovative use of digital technologies for fear of inadvertently breaching system policies or creating privacy risks or c) utilizing new technologies without consideration of personal or family privacy risks or d) adopting new technologies believing all care has been taken but where risks remain because of skill deficits or because the expertise is unavailable. For example, when adopting a new cloud-based application for learning, consideration may be given to secure consent from parents and perhaps students with due care to data retention. Or consideration surrounding cloud security may be considered without concern about local network security or local authentication (password management). Another option is to secure the data through an agreement with the cloud-based service provider.

The requirement to consider privacy within educational systems can lead to privacy avoidance where privacy policies and consequent decisions are avoided for lack of expertise or avoidance of complexity. This void often leaves front-line educators to figure it out on their own or to interpret policies without the skills or foundational knowledge. The consequence can often be, a) to avoid digital technologies or minimize their use in educational settings, b) avoid any innovative use of digital technologies for fear of inadvertently breaching system policies or creating privacy risks or c) utilizing new technologies without consideration of personal or family privacy risks or d) adopting new technologies believing all care has been taken but where risks remain because of skill deficits or because the expertise is unavailable. For example, when adopting a new cloud-based application for learning, consideration may be given to secure consent from parents and perhaps students with due care to data retention. Or consideration surrounding cloud security may be considered without concern about local network security or local authentication (password management). Another option is to secure the data through an agreement with the cloud-based service provider.

A central leadership task for system leaders is to support personnel to acquire both high-level instructional skills while also acquiring technological knowledge to inform and lead the use of learning technologies. The different career paths and formal education followed by educators and computer science professionals often lead to perspectives that are domain-specific and omit a holistic view of issues facing educators when addressing privacy issues in school systems. The figure above outlines the overlapping and complementary skill sets required in an increasingly digitized learning environment. Consequently, one of the central questions within educational settings is to answer the question,

How can educational systems support leaders to acquire both deep technological skills while also possessing educational competencies that can help leaders answer the following questions from a variety of perspectives.

- What does privacy mean in educational settings?

- What are the leadership tasks required to address protecting student privacy?

- How do educational leaders ensure the collection and retention of student data is thoughtful and time-limited?

- What tasks are required to develop and ensure privacy concerns are embedded across schooling curriculums?

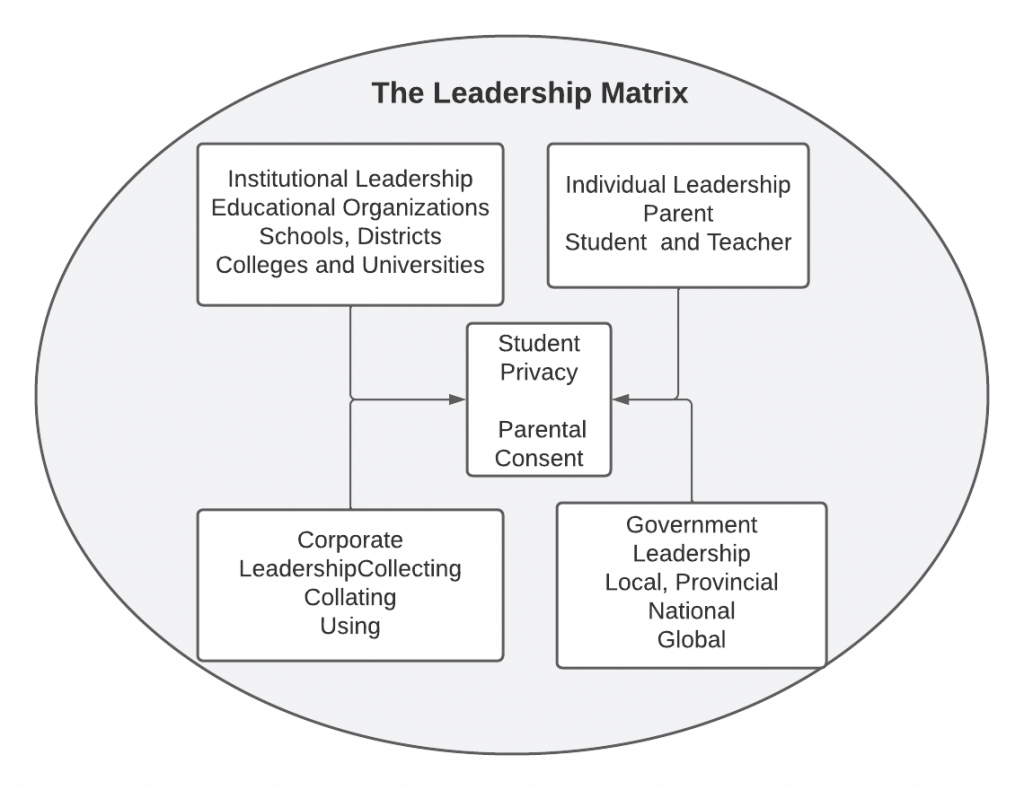

The Leadership Matrix

Educational leaders already operate in a complex environment where considerations about privacy are diverse and multi-faceted. Teachers may view privacy through a lens of how best to support student achievement, believing that systems or school administration are best able to manage privacy concerns and specific privacy settings. Administrators can view privacy through a lens of risk avoidance where restricting the potential use of particular classroom tools is often considered key. Parents, on the other hand, view privacy through a lens of concern for their children but cede their concerns to school systems through trusting educators to protect their children from harm. Finally, students are often the last to be consulted, if at all, and may have a curriculum that is silent on the concepts of consent and privacy when using digital technologies. A consequence of this diverse set of beliefs is that privacy is considered important but the responsibility for privacy is left to others to manage.

Figure 2.

The Leadership Matrix.

In the Digital Privacy: Leadership and Policy course, the authors have discussed the complexity of privacy responsibilities, the privacy paradox and the growing use of artificial intelligence and machine learning, the use of mobile devices, digital surveillance, the complexity of policies for regulating student privacy and the real potential for the misuse of personal information. Yet, the roles and responsibilities of educational leaders and other actors within schooling settings regarding protecting student privacy and misuse of student data remain less well examined in the academic and professional literature. Schrum and Levin (2015) write that, while school or district leaders cannot be expected to do everything alone, they must think systemically and utilize skills and strategies of distributed leadership to engage others and create a shared vision for technologies in schools. As members of the course authorship team, we hope to raise awareness of privacy as a vital component of technology adoption and use. The leadership challenge of consultation with many players while attempting to create consensus around issues that are sometimes at odds with other beliefs has only compounded the necessity to conceptualize the leadership matrix (Figure 2) where student privacy and safety is both an educational issue and a societal one. While boundary issues abound when considering student privacy, the leadership challenge is to acknowledge boundary issues and manage that which is within the scope of school administrators.

In the Digital Privacy: Leadership and Policy course, the authors have discussed the complexity of privacy responsibilities, the privacy paradox and the growing use of artificial intelligence and machine learning, the use of mobile devices, digital surveillance, the complexity of policies for regulating student privacy and the real potential for the misuse of personal information. Yet, the roles and responsibilities of educational leaders and other actors within schooling settings regarding protecting student privacy and misuse of student data remain less well examined in the academic and professional literature. Schrum and Levin (2015) write that, while school or district leaders cannot be expected to do everything alone, they must think systemically and utilize skills and strategies of distributed leadership to engage others and create a shared vision for technologies in schools. As members of the course authorship team, we hope to raise awareness of privacy as a vital component of technology adoption and use. The leadership challenge of consultation with many players while attempting to create consensus around issues that are sometimes at odds with other beliefs has only compounded the necessity to conceptualize the leadership matrix (Figure 2) where student privacy and safety is both an educational issue and a societal one. While boundary issues abound when considering student privacy, the leadership challenge is to acknowledge boundary issues and manage that which is within the scope of school administrators.

Cloud-Based Applications: Convenience and Risk

The requirement to provide leadership about privacy has never been more acute for educational leaders. The emergence of a global pandemic in 2019 and the subsequent closing of schools and the move to embracing online learning and/or learning from home has resulted in education moving from the school and classroom to the virtual classroom. The recent pivot to learning online throughout the global pandemic has only highlighted the complex issues and problems of protecting student privacy in online and learning at home settings. Moving from a face-to-face environment to an online environment has often resulted in the additional and inappropriate collection of children’s personal information. Han (2020) observes that, while many online teaching platforms are depicted as transactional in nature to facilitate interactions and learning online, the collection of student information and potential collection of student presence through video screen recording, screen capture and chat archiving presents serious concerns for privacy and how to protect children from privacy risks.

This was echoed by the 2020 report from the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development concerning the effect of Covid 19 on children (Thevenon & Adema, 2020) which pointed out that the pivot to online learning presented unique challenges regarding data collection and retention of personal information used to access and monitor student engagement in online activities. Online learning and the facilitation of learning through Internet activities only intensified the difficulties faced by school leaders when consulting with the myriad actors and intersecting policies that required consideration. This pivot to online learning was enabled by the use of online digital tools and in some cases the distribution of computing hardware and software to students at home. From Zoom classes to Google Classroom, Microsoft Teams, Edsby, and Emodo Canvas, school districts embraced new tools to organize and continue education at home. Additionally, tools such as PearDeck, Storybird, Kahoot! and Class Dojo, among many others, emerged as instructional, communication or companions to school learning management systems. But with the pivot to learning online, so too came questions about how to manage student privacy, how best to manage student login information, how to document learning and the associated learning activity record, and how to document students’ learning. The shift to online also heightened the need to identify which policies should be developed to guard against the over-capture of student data as well as its retention.

Leadership Responses Privacy Gaps in Curriculum Policies

Educators wishing to provide leadership on issues concerning student privacy and safe Internet usage involve not only administrative competence but curricular leadership to support student empowerment to make informed choices about personal safety online. The inclusion of privacy across the curriculum includes a recognition that protecting students’ privacy is an ethical concern. Choice is not only about asking for consent but asking again and again. This becomes more difficult in an era of persuasive technology. Smids (2012) gives the example of the sound made by the car if anyone does not fasten their seat belt. The continuous sound is a persuasive technology and also a coercive technology. A persuasive technology that allows voluntariness would be the example where the seat belt reminder rings once or twice and then stop without compelling someone to put their seat belt on. Smids (2012) suggests an ethical requirement of voluntarism is that it should be intentional, free from controlling influences, and is an informed decision. It requires leadership to make certain that voluntariness is part of informed consent and that this applies to all online learning applications.

Teachers, students, families, staff all share concerns about individual privacy and the trust that their online actions are free from privacy risks. Educational leaders bear a responsibility to support the development of resources to support educating students about privacy risks and their online presence. Moon (2018) observes that,

Students lack the knowledge they require to participate safely in a digital world creating a gap in understanding. Access to knowledge is required to foster understanding and create informed students that have learned the skills they will need to navigate the potential harms of digital access. (p. 292)

Curricular leadership involves not just ensuring resources are available but actively involving oneself as a leader in multiple ways:

- Ensuring curricula align with provincial outcomes where available,

- Establishing frameworks to measure goals while establishing timelines for assessing progress,

- Ensuring that curriculum resources are age and stage appropriate,

- Assisting in identifying cross-curricular approaches to privacy and safe internet use,

- Ensuring that the school systems values are embedded and reflected in all aspects of curricula, and

- Supporting students and families from across diverse backgrounds.

Curriculum policies must not only be a checklist of do’s and don’ts but also includes giving students the knowledge to avoid harm, challenging what appropriate online behaviours are expected, internet safety and considerations about the use of social media including awareness about and how to respond to inappropriate invitations, solicitations and grooming online. The curriculum can include discussions about responsible online use, school codes of conduct and acceptable use policies.

Examples of topics to be included in privacy-focused curricula include topics and concepts about a) greeting a healthy balance between online and offline behaviours b) how to engage in online activities from an ethical base of understanding risk, consequences while understanding others, c) making purposeful choices to protect personal information about oneself and others, d) building healthy relationships online and e) developing good habits and understandings about hardware settings to address online security. More specifically, topics such as public Wi-Fi risks, gaming and online security, passwords and their use, recognizing and managing phishing and spam, how to read terms of service when using cloud-based applications and how to circumvent flirting and sexting overtures online.

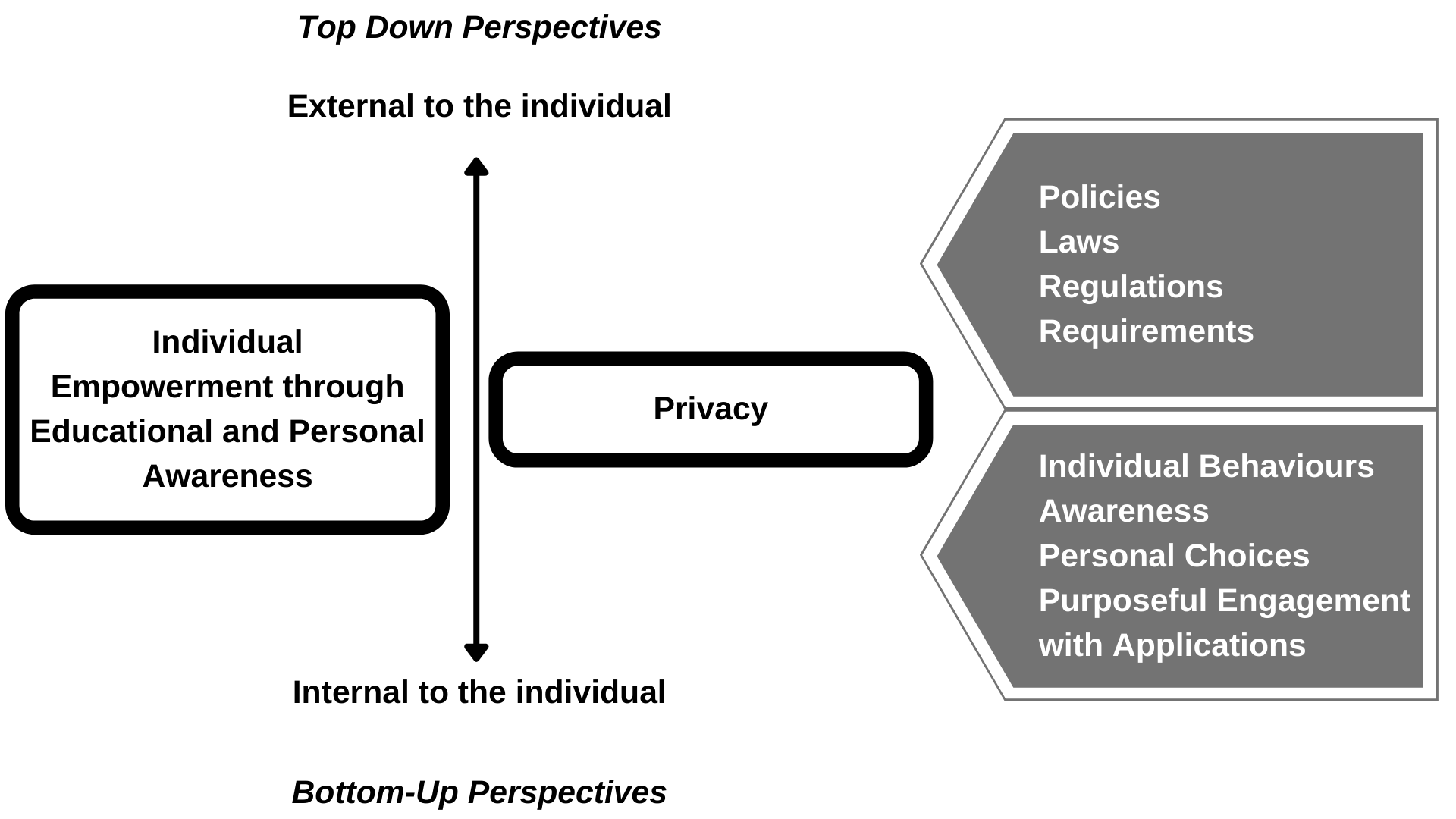

Figure 3.

Top down and bottom-up perspectives.

To help leaders to conceptualize learning outcomes for privacy initiatives in a post-digital age, the authors debated what it meant to be private and how to understand the push and pull of being a digital citizen in today’s world. If the goal of privacy is to enable everyone to engage with the rich experiences that digital technologies can offer and the interconnectedness with persons, services and resources online that the Internet has to offer, it is essential to empower everyone (most especially children) about how to protect and secure one’s self in an environment where the privacy paradox, the legislative environment, monetization of online behaviours and trans-generational views about digital citizenship are under development and shaped by past and current experiences. In trying to understand the role of educators and what leadership they can offer to a world in flux, we settled on the overarching goal of empowering young people to be aware of changes around them and inspire them to make purposeful decisions about how they will live their lives now and into the future. The figure offers a sense of both top-down efforts to protect and create proactive actions to protect privacy while concurrently efforts to empower and educate children about their own privacy actions to make personal choices about engaging in the online world in which they now live, will work and will occupy throughout their lives. Just as the digital/online world will comprise the present and future so too with concerns about privacy. The answer, therefore, is to educate and empower the citizens (students) for the future.

Recommendations for Educational Leaders

We offer the following recommendations in support of more privacy-conscious learning environments. The recommendations are not comprehensive; they are a first step in addressing the leadership gap regarding privacy considerations in education.

- Leaders must embrace a privacy orientation across all operations and learning contexts to ensure not only compliance with existing policies and laws but also to ensure that privacy is at the forefront of teaching and learning.

- Leaders must ensure they possess or ensure they can acquire technological knowledge and skills in areas of privacy and security to complement their experience as educators

- Leaders must designate a single point of contact to ensure privacy is not an afterthought but is a designated/defined responsibility within educational operations.

- Leaders must support the creation of an annual privacy report including reporting on privacy breaches and ongoing privacy risks.

- Leaders must engage with all those with whom the educational enterprise touches to ensure that information about and decisions about privacy risk abatement are communicated.

- Leaders must ensure that privacy concerns, required actions and exploring privacy values are embedded across curriculum policies with age-appropriate resources to support front-line educators.

- Leaders must ensure that consent for technological services is updated and that asking for consent once is not informed consent.

- Leaders must establish policies regarding data access and data retention across all educational operations.

- Leaders are encouraged to reflect on technological use and the values inherent in the adoption of emerging technologies with specific attention to technologies associated with school safety and surveillance.

- Leaders must ensure that digital citizenship efforts equip students to be proactive versus reactive when managing their presence and behaviour on the Internet.

Some Closing Thoughts

Educators in the present era find themselves within a vortex of rapid technology innovation. It is also a time of significant social disruption. This is happening not only for health concerns but as technology enables the disclosure of crimes against humanity as they occur in real-time, and as they are unearthed from the past. Technology has also enabled the voices of those who have been at the margins of society and seek their rightful membership in society.

At the heart of all educational endeavours, educators hold the safety, security and well-being of the students who have been entrusted to them for education, as well as the students who have chosen their educational institution. These students will need the skills to solve problems during times of great complexity and innovation. Digital privacy is one of those messy, authentic problems of progress. As leaders work toward solutions, they need to model the skills advocated in this online course: ethical problem-solving; knowledge sharing and knowledge building through communication and collaboration; and decision-making guided by critical, reflective practice.

We invite the instructors and students who take the Digital Privacy course to contribute case studies and examples in Chapter 10. This will help to evergreen the course and provide sector-specific examples of authentic digital privacy case studies.

References

Balsillie, J. (2019, May 28). Jim Balsillie: ‘Data is not the new oil – it’s the new plutonium’. Financial Post. https://financialpost.com/technology/jim-balsillie-data-is-not-the-new-oil-its-the-new-plutonium

Brooks, D. (2013, February 05). The philosophy of data. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/05/opinion/brooks-the-philosophy-of-data.html

Han, H. J. (2020). As schools close over coronavirus, protect kids’ privacy in online learning. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/27/schools-close-over-coronavirus-protect-kids-privacy-online-learning

Moon, E. C. (2018). Teaching students out of harm’s way. Journal of Information, Communication & Ethics in Society, 16(3), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICES-02-2018-0012

Jennings, N. (2021, January 07). Lighthouse starry night [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/VsPsf4F5Pi0

Nagel, D. (2018). Student data privacy a top concern of K-12 tech leaders. THE (Technological Horizons In Education) Journal, 45(4), 34. https://digital.1105media.com/THEJournal/2018/THE_1810/TJ_1810Q1.html#p=34

Schrum, L., & Levin, B. B. (2016). Educational technologies and twenty-first-century leadership for learning. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 19(1), 17-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2015.1096078

Smids, J. (2012). The voluntariness of persuasive technology. In M. Bang, & E. L. Ragnemalm (Eds.), International Conference on Persuasive Technology: Persuasive technology, design for health and safety (pp. 123–132). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31037-9_11

Thevenon, O., & Adema, W. (2020, August 11). Combatting COVID-19’s effect on children. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/combatting-covid-19-s-effect-on-children-2e1f3b2f/

Webster, M. D. (2017). Philosophy of technology assumptions in educational technology Leadership. Educational Technology & Society, 20(1), 25–36. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.20.1.25