2 Digital Privacy in Education

Lorayne Robertson and Laurie Corrigan

This chapter will assist students to:

- Explain how changes in the digital landscape have impacted digital privacy in schools.

- Critically weigh different approaches to building students’ digital privacy capacity.

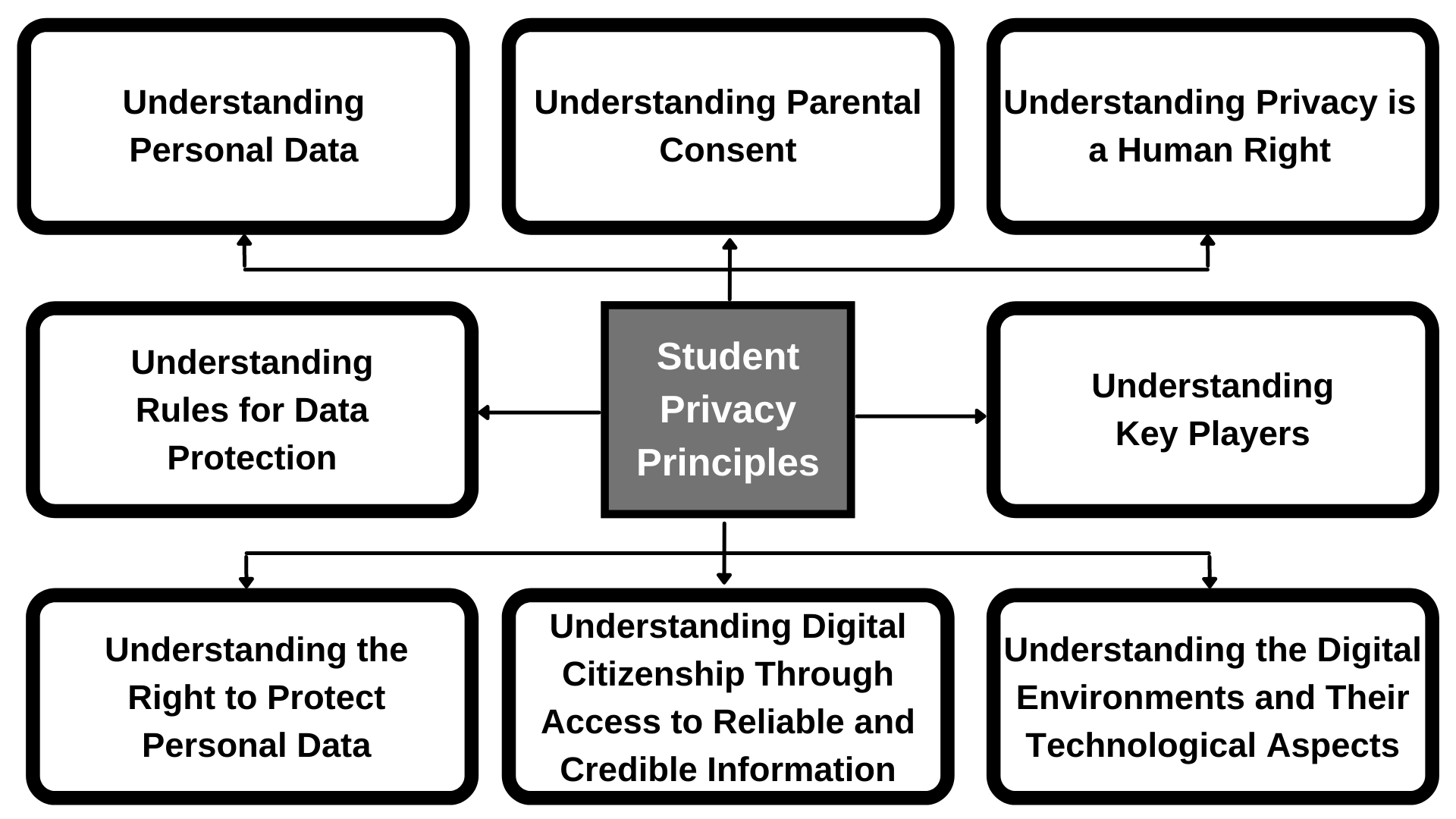

In this chapter on digital privacy in education, we explore how digital technology and artificial intelligence have greatly expanded both the opportunities for internet use and for increased digital surveillance. We examine the educational implications of data surveillance and consider the role of schools in an era that is characterized by the steady creep of passive data collection. Secondly, we ask questions of educators regarding the types of curriculum and policy responses that are needed. Finally, we argue for a much more critical examination of the role of digital privacy and surveillance in schools. Figure 1 outlines our reflection of student privacy principles in this chapter.

Figure 1.

Student privacy principles.

Digital privacy solutions for students are multi-faceted. Students need to understand what constitutes personal data and understand that privacy is a human right. They need to understand the context of the present digital environment, and that there are multiple players in the system who are looking to have access to their data or looking to protect their data. Students also need to acquire skills of digital citizenship so that they understand that information can be curated and mediated. They need to know how to access credible, reliable information. Finally, students need to understand why it is important to protect their personal information and why there are rules for data protection. Students of vulnerable ages need to know how to work with their parents’ supervision in order to protect their data. In sum, the overall picture for digital privacy in education is complicated!

Key topics in this chapter are as follows:

- The context (landscape) for internet use in Canada.

- Connecting digital surveillance and digital privacy.

- Protecting students’ digital privacy as a shared responsibility.

- Framing discussions about digital privacy in education.

1. Internet Use: The Canadian Context

In 2020, Canada was in the throes of a global pandemic, and Canadians were required to work from home and attend school remotely. Many changes in Canadians’ internet usage occurred in the five years that led up to the pandemic and there were more changes during the pandemic. Statistics Canada (2021) reports that many Canadians considered the internet to be a lifeline during the first waves of the pandemic. Four out of five Canadians shopped online, and their online spending rose significantly (Statistics Canada, 2021). Four out of five Canadians watched streamed content, with 38% reporting that they watched more than ten hours in a typical week (Statistics Canada, 2021). Not surprisingly, more than two-thirds of Canadians used the internet to monitor their health (Statistics Canada, 2021). The statistics were clear also for young Canadians; the vast majority (98%) of young Canadians reported that they were using the internet (Statistics Canada, 2021). Smartphone use also increased with 84% of Canadians reporting that they used a smartphone to communicate (Statistics Canada, 2021). Almost half of this group reported that they check their phone every half hour (Statistics Canada, 2021).

The prevalence of devices such as laptops, Chromebooks, and cell phones with their related applications, as well as the emergence of smart home devices have done more than simply change the technology landscape. As technology has increasingly become such a big part of people’s lives, the result has been a gradual decrease or erosion of Canadians’ privacy. This is happening for multiple reasons. First, the users lack the time to read, understand and give informed consent, which we would define as consent with full awareness of the risks involved. The Office of the Privacy Commission defines meaningful consent as a knowledge of what information is being collected, the purpose for the collection, how the information will be shared, and understanding of the risks and consequences. Secondly, privacy agreements are long and convoluted. Third, with so many Canadians accessing the internet on their phones, and so many young people using the phone for social media, gaming and instant messaging, the fine print of privacy policies read on phones is so small that it almost necessitates click-through rather than a detailed study of the implications of agreeing to a disclosure of privacy. Even the Canadian Internet Registration Authority requires the download of an app and a series of instructions in order to provide users with screening tools for pop-up advertising on devices.

A critical examination of digital privacy requires stepping back and taking a deeper look at what is happening. Parents and educators also need to analyze what is happening, as they are the role models and imprinters for their children and students who navigate the digital world. We argue in this chapter that Canadians must consider multiple threats to individual privacy. Some of these threats include the collection and marketing of personal data. Other threats involve increasing surveillance of youth by trusted adults without consideration of the implications of over-surveillance for their individual privacy.

In Canada, The Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) was making recommendations to protect the online privacy of Canadian children as early as 2008 (OPC, 2008). The Privacy Commissioner urged providers of content for youth to ensure that young people visiting websites could read and understand the terms of use. The Privacy Commissioner website focuses on two aspects of online activity in youth: personal information protection and online identity and reputation. No legislation, however, has been presented in Canada to protect the information of children and youth, leaving children’s privacy largely unprotected as it relates to educational content and policy. Central concepts of digital privacy such as digital footprint, digital dossier and digital permanence have not found their way into everyday curriculum policies.

Confounding the issue of digital privacy protection for children and adolescents is the patchwork of policy solutions. For example, Canada has devolved responsibility for education to the provinces and territories, which design operational and curriculum policies (Robertson & Corrigan, 2018). In Ontario, however, municipalities and cities oversee the protection of personal information. The Municipal Freedom of Information and Right to Privacy Act (MFIPPA; 2021) defines personal information as recorded information that can be used to find someone’s identity. This recorded information about an individual includes the following areas and more: a) race, origin, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, or marital status; b) educational, medical, psychiatric, criminal, or employment history; c) any identifying number or symbol; and d) address, telephone, fingerprints, blood type, and name. There is little in the MFIPPA policy to indicate that it has been updated to the digital realm, although it does acknowledge that a record could be electronic (1990, p. 3). MFIPPA states that institutions shall not use personal information in their custody (S. 31) unless they have consent (Robertson & Corrigan, 2018).

In summary, the context of digital privacy in Canada is one where reliance on the Internet for education, work and leisure is increasing. Digital/mobile applications require consent to use them, but the consent forms are lengthy and difficult to decipher. A patchwork of national, provincial and municipal services oversees privacy. The office of the Privacy Commissioner of Ontario provides advice, but there is little coordination evident between the offices overseeing privacy and the provincial designers of curriculum and operations in education. There appears to be an agreement in policy that personal information should be protected, but there has been no pathway forward to design comprehensive privacy protection.

2. Pervasive Surveillance and Digital Privacy

Another key aspect of the present context is that of surveillance, which has become so much a part of our lives that it has quite literally become a backdrop to the everyday. In this section of the chapter, we discuss the collection of human experiences as behavioural data as one form of surveillance. In addition, we review how surveillance can also be packaged and sold as student safety measures.

Recently, a colleague purchased potato chips with cash at a convenience store. The next day, when he received pop-up advertisements for chips on his home computer, he wondered if it could be a coincidence. Since he did not use a bank card or a credit card for the initial purchase, he thought his purchase was anonymous. He was unaware of the hidden workings of surveillance cameras in stores and how his phone and other devices were tracking his whereabouts. He was also unaware that data about his purchasing habits and location were potentially being captured and shared without his express consent. He was certainly not aware that data related to his purchasing habits were being sold and shared.

The New York Times Privacy Project made the claim that location data from sources hidden in mobile phone apps have made an open book of the movements of millions of Americans, as it is recording who and where they visit and for how long. Some of the data is recorded by unregulated and unscrutinized companies (Thompson & Warzel, 2019). Similar claims have been made in Canada that Google and Facebook are tracking users’ search data for marketing purposes (Dangerfield, 2018). Key critical questions need to be asked and answered regarding the rights of individuals to privacy and the growing apathy and immobility to challenge digital surveillance for corporate gain.

The Center for Democracy and Technology in the United States has recently raised issues of pervasive student surveillance on school-owned computers distributed during emergency remote learning. In a letter to the US Senate, they suggest that,

Student activity monitoring software can permit school staff to remotely view students’ computer screens, open applications, block sites, scan student communications, and view browsing histories. It may utilize untested algorithmic technology to flag student content for review, and security flaws have also permitted school personnel to access students’ cameras and microphones without students’ permission or awareness. (Venzke & Laird, 2021, p. 1)

Haskins (2019) argues that almost five million students in the US are being watched online in schools by the surveillance industry and students do not have the opportunity to opt-out of being watched. She reports that Gaggle uses a combination of artificial intelligence and human moderators to track students’ emails and their online work, including messages that come into the cloud-based learning site from social media. One of the concerns she raises is that LGBTQ words are on the banned words list. She also raises the overall concern that students are subject to relentless inspection. She questions if the cost of this surveillance reflects the real priorities of school districts (Haskins, 2019).

Hankerson et al. (2021) report that surveillance of student devices treats different groups of students differently. Students using the school’s digital devices are monitored more than students with personal devices. Students from poverty are less likely to own personal devices and are therefore monitored more. Local education authorities in the United States are seeking student activity monitoring vendors to surveil students in the name of protection of digital privacy. Similarly, Feathers (2019) reports that, in the United States, schools use snooping tools to ensure student safety, but some studies looking into the impact of these tools are showing that they may have the opposite effect—such as damaging trust relationships and discouraging communities of students (e.g., LGBTQ) who look for help online.

Despite these reports, a survey for the Center for Democracy and Technology (2021) in the United States finds that parents and teachers acknowledge the privacy concerns, but they see that the benefits of student activity monitoring outweigh the risks (Grant-Chapman et al., 2021).

Fisk (2016) has raised different but equally important concerns about the surveillance of youth. As they have increasingly documented their lives online (e.g., through Instagram, TikTok, etc.), adult surveillance of their lives has increased to monitor many of the previously unsupervised spaces in their lives. Fisk has identified pedagogies of surveillance (p. 71) that observe, document and police the behaviours of youth. Parents, for example, use the tracking devices on their children’s phones or fitness apps to monitor their whereabouts. Internet safety presentations are designed to destabilize parents’ awareness of what youth are doing online and sell internet safety to parents and guardians. A critical examination of these practices asks: Who profits from these youth surveillance initiatives? Who are the winners and the losers? Do young people have a right to know when they are being monitored online?

Palfrey et al. (2010) at the Harvard Law school argue compellingly that youth need to have an opportunity to learn about digital privacy and acquire digital privacy protection skills. They explain in the following way,

We also need to begin the conversation with a realization that adult‐driven initiatives – while an important piece of the puzzle – can only do so much. Youth must learn how to handle different situations online and develop healthy Internet practices. Through experience, many youths are able to work out how to navigate networked media in a productive manner. They struggle, like all of us, to understand what privacy and identity mean in a networked world. They learn that not everyone they meet online has their best intentions in mind, including and especially their peers. As with traditional public spaces, youth gain a lot from adult (as well as peer‐based) guidance. (Palfrey et al., 2010, p.2)

There are mixed messages with respect to who has the responsibility to teach and reinforce internet safety guidelines to protect students’ privacy. MediaSmarts, which is a Canadian nonprofit, reports in one study (Steeves, 2014) that more students said that they learned about internet safety from their parents than from the school. Students say that their teachers are more likely to help them in other ways, such as helping them search for information online and how to deal with cyberbullying than to teach them about digital privacy. The reality is that parents cannot assume that teachers are addressing digital privacy and teachers cannot assume that parents are doing this. Digital privacy education is a shared responsibility.

Students may not know that their digital footprint, which is the list of all the places they have visited online, is searchable and can be connected back to them. Some of the data is collected actively, through logins. Some of the digital footprint, such as which websites are visited and for how long, is collected passively as they are web surfing—this data is called clickstream data because it shows where a user has navigated online (Solove, 2004). Another means of passive data collection is through cookies or tags which are small sets of codes that are deployed into the user’s computer when they visit a website.

One company capitalizes on clickstream data via DoubleClick, which accesses cookies on the user’s computer, looks up the person’s profile and then sends advertisements targeted specifically for that person in milliseconds. Hill (2012) explains how one company, Target, looked over customers’ purchases and predicted whether or not they might be pregnant. After a father complained that his daughter was receiving targeted baby product ads, the company began disguising this targeted advertising by putting ads for lawn equipment beside the baby ads. In 2004, DoubleClick had more than 80 million customer profiles (Solove, 2004). This changed significantly when Google purchased DoubleClick.

According to Lohr (2020), the acquisition of DoubleClick by Google in 2007 was a significant game-changer for Google because Google in 2007 was one-tenth of the size that it became by 2020. At present, Google owns the leading browser globally with accompanying email, meeting space and other software, but the source of most of its tremendous profits is its advertising (Lohr, 2020). The dominance of Google has led to investigations by the Justice Department (Geary, 2012; Lohr, 2020) and the filing of an antitrust lawsuit on its search engine in October 2021. Hatmaker (2021) reports an additional antitrust lawsuit over Google Play was filed in July 2021.

According to Geary (2012), DoubleClick (Google) operates two categories of behavioural targeting. For the first, a website owner can set a DoubleClick cookie to track which sections of their website you are browsing. DoubleClick also tells advertisers how long the ad is shown and how often it will appear to the user. Secondly, Google runs Adsense, where different publishers pool the information from browsers; this is third-party advertising. The two systems can work together to categorize the person’s ad preferences. Categories are established to help advertisers target directly to you. As a user, you can visit Google’s ad preferences manager to see how your preferences have been categorized.

Students also may not understand digital permanence, which is the understanding that data posted online is very difficult (impossible) to delete. Students may not be aware that inappropriate or thoughtless messages posted today can impact future employment. They may also not be thinking that humour to a pre-teen may not be the humour they will appreciate when they are older. Some studies show that young people do care about privacy and want to protect their information (Palfrey et al., 2010; Steeves, 2014). The issue remains, however, that there is no clear national direction or consensus on the protection of personal information that also limits the degree of passive surveillance permitted by law.

The collection of information about us without our consent is not a new phenomenon. According to Solove (2004), in the 1970s, the American government started selling census data tapes. They sold the information in clusters of 1500 homes with only the addresses (no names). Marketing companies matched the addresses using phone books and voter registration lists (Solove, 2004). Within 5 years, they had built databases for over half of American households (Solove, 2004). In the 1980s, they wanted to add psychological kinds of information about beliefs and values, which led to the creation of taxonomies of people groups who had income, race, hobbies and values in common. By 2001, the marketing of these databases, which allows advertisers to target your mail, email or phone through telemarketing, grossed over $2 trillion in sales (Solove, 2004). Yet, it is not possible to sign up for a bank account or a credit card without offering up much of your personal information (Solove, 2004).

Zuboff (2020) argues that a new economic logic is now in place, which has been relatively unchallenged through policy. She defines surveillance capitalism as a practice that claims that human experience is free material for hidden commercial data extraction, prediction, and sales. These practices are allowed to proliferate because the dangerous illusion persists that privacy is private (Zuboff, 2020). In surveillance capitalism, human experience is captured by different mechanisms, and the data are reconstituted as behaviour. This data capture is allowed to continue when customers give up pieces of themselves and when pieces of their information are taken from them without their knowledge. This concentrates wealth, knowledge and information in the hands of a few for profit. For example, Facebook produces 6 million predictions every second for commercial purposes. No one could easily replicate Facebook’s power to compile data (Zuboff, 2019).

According to Van Zoonen (2016), the general public is complicit in releasing their information. Despite indicating that they have privacy concerns, they use simple passcodes and share these codes among devices. They share their personal information on social media sites and, in general, while they do not believe that their nationality, gender or age is sensitive information, they are increasingly concerned about how data might be combined for personal profiles. They want to weigh the purpose of the data collection and assess whether the benefits outweigh the risks. The request for too much data, for example, might outweigh the benefits (Van Zoonen, 2016).

The protection of personally identifiable information for youth is even more important because they are learning the skills toward understanding consent. Also, schools may be unknowingly complicit in providing third-party access to student information through educational apps. It makes sense, therefore, that schools should guide students in the reasons behind protecting their digital privacy and help them to understand it (Robertson & Muirhead, 2020).

Some key lessons about digital privacy for Canadian students in the 21st century to understand include:

- how their data is being collected and for what purpose,

- how long their data will be retained,

- what constitutes informed consent, and

- the difference between voluntary and passive data capture.

3. Digital Privacy as a Shared Responsibility

Digital technologies are advancing at such an unprecedented speed that neither the curriculum nor the general policy guidelines in education can keep pace, resulting in curriculum and policy gaps surrounding digital privacy in education. The protection of personally identifiable information (PII) has a different level of importance for youth because there are greater risks for their safety and their age may make them less able to give informed consent. Without a clear understanding, schools and school districts might be unknowingly complicit in providing third-party access to student information through educational apps. It makes sense to put in place an expectation that students who use technology in schools also need opportunities to gain an understanding of digital privacy. In the United States, for example, the Children’s Internet Protection Act requires schools that receive funding for technology must also provide students with education about online behaviour (Federal Communications Commission, 2020).

A Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN) was established in 2010 (GPEN, 2017) composed of 60 global privacy regulators. These experts cautioned that teaching platforms that are internet-based can put students at risk for the disclosure of their personal information. In a 2017 review, GPEN found that most online educational apps required teachers and students to provide their emails to access a particular educational service or app, thereby providing a link to their PII. Only one-third of the educational apps reviewed allowed the teachers to create virtual classes where students’ identities could be masked (GPEN, 2017). Although teachers complied with requests to provide the students’ actual names, they found that it was difficult to delete these class lists at the end of term. While most of the online educational services restrict access to student data, almost one-third of the educational apps reviewed in the GPEN sweep did not provide helpful ways for students to opt-out or to block third party access to their data (GPEN, 2017) taking away their right to make a privacy decision, let alone an informed privacy decision.

The findings of the GPEN sweep are understandable given the speed at which educational apps have proliferated. The curriculum has not been able to keep pace. There are a number of key understandings that have not been a part of the school curriculum for generations of digital users. According to a Canadian policy brief (Bradshaw et al., 2013), here are some examples:

- Personally-identifiable information (PII) – Students should also understand what constitutes PII as this can vary from person to person. Bradshaw et al. (2013) identified four common categories of privacy-sensitive information:

- Personally-identifiable information: such as the name of the user, credit card numbers and IP addresses.

- Lifestyle information: such as race, religion, relationship status, sexual orientation, political affiliations, friends and family members.

- Behavioural data: such as viewing habits, websites visited and time spent; online purchases, store loyalty programs and credit cards.

- Unique device identifiers: such as user location, determined by globally unique identifiers connected to mobile devices.

- Passive data capture: Students, teachers and parents need to understand different forms of data capture. Passive capture happens when data is taken without the knowledge of the person. Other data is shared with permission.

Note. Free WiFi inside, by B. Herman, 2018. In the present era, it is sometimes hard to distinguish between these two. For example, if a person wishes to use the store’s wifi, they might click-through the privacy agreement without reading it. By doing this, they are agreeing to broader data capture, such as where they pause in the store to look at merchandise. Some third-party applications that collect student data may require parents to click through the privacy agreements. These agreements tend to be long and difficult to understand. This prevents parents from gaining a clear and concise explanation of the implications of sharing their children’s data.

- Data recombination: While people are generally careful about sharing their credit card information and personal identifiers, they may not be aware that they are also passively sharing other information that can reveal their identity. For example, small amounts of simple demographic information can be recombined in order to identify a person uniquely. In one study, postal code, date of birth and gender were combined to identify 87% of Americans uniquely (Sweeney, 2004). Movie preferences can generate similar identifications (Ohm, 2010). This is a consequence of data recombination that occurs when large amounts of data are collected and sold in a largely unregulated online marketplace.

- Behavioural micro-targeting: This is a technique that targets future advertising to potential customers based on an analysis of website use. Companies track digital transactions and websites visited, aggregate the data and sell the information for political or advertising purposes. Google (owner of DoubleClick discussed earlier in this chapter) announced that this was being undertaken to make advertising more relevant for its users (Wojcicki, 2009). Geary (2012) writes that Google claims that tracking people gives them the benefits of making the advertising more relevant, controlling how many times the user has to see the ad and also allows a way for savvy web users to control and block advertisers (Geary, 2012).

-

Note. Scrolling apps, by R. Hampson, 2017. Loyalty apps: Students need to be made aware that loyalty cards collect more than the points that they advertise in order to draw in customers. McLeod (2020) reported that his coffee order app had located his whereabouts both at his home and work address. This occurred when he was in Canada and on vacation. Through combinations of networks, the app tracked him throughout the day and night—in total reporting his location 2,700 times in five months. He had incorrectly assumed that the app was working only when he was ordering his morning coffee (MCleod, 2020).

These examples illustrate that understanding consent is a central concept in understanding digital privacy.

PIPEDA: Canada’s regulatory guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent are outlined in the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA; 2016). This legislation regulates privacy for the private (commercial) sector in Canada and is not specific to education or youth. In comparison, the American Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (COPPA; 1998) designates the age of 13 as the minimum age for young persons to have an online profile. This legislation was designed to protect young internet users, but recent research shows that there are many underage users on the internet, raising questions about whether or not legislation is the answer (Hargittai et al, 2011).

There is a gap in the national legislative direction in Canada that is designed to protect the personal information of all Canadians, including young people. There are also key understandings that should become part of basic education on internet use.

| While PIPEDA does not provide privacy guidance, it regulates the commercial sector through key principles for fair information practices. These are as follows:

Notice: Users should be informed when information is collected, for what purpose, how long it will be used, and how it will be shared. Choice: Users should have a choice about whether or not they share their information. Access: Users should be able to check and confirm their information on request. Security: The users’ information should be protected from unauthorized access. Scope: Only the required information can be collected. Purpose: The purpose for collecting the information should be disclosed. Limitations: There should be a time limit on how long the information will be held. Accountability: Organizations should ensure that their privacy policies are followed. |

In California, a Shine the Light (2003) law requires list brokerages to tell people on request where they have sold their personal information (Electronic Privacy Information Center, 2017). To the best of our knowledge, no similar legislation exists to protect the digital privacy of Canadian children and adolescents. Chen examined the digital divide in Ontario schools and notes, “to date there is no national policy on digital learning in place” (Chen, 2015, p.4). Without a systematic approach to digital learning, the school districts are left to define digital curriculum learning outcomes on their own. While education falls to the provinces and territories, the Annual Report of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario (IPC) (2020) does not give direction to education in Ontario. The Ontario Government report: Building a Digital Ontario (2021) does not address digital privacy in education. Recently, the Ontario government has made clear that digital privacy policies and terms of use are the responsibility of local school districts (Information and Privacy Commission for Ontario, 2019; Ministry of Education, 2020).

One province in Canada, Ontario, has written a policy (Bill 13) that holds students accountable for their online activities if they impact other students negatively. Bill 13: The Accepting Schools Act (2012) requires schools to address harassment, bullying, and discrimination using a number of interventions that include suspension and expulsion. Specifically, it identifies cyberbullying behaviours, such as the online impersonation of others, and makes digital bullies subject to the consequences enacted in the legislation, including suspensions, expulsions, and police intervention. While the scope and sanctions of the Accepting Schools Act have given schools the authority to respond to cyberbullying and online aggression, it does not focus on or include language that develops the digital citizenship of students. It also does not address the professional development of teachers who, ten years after its assent, now teach students who are even more immersed in the technologies that can lead to school-based consequences.

Shared Responsibility

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has 38 member countries, including Canada. They have published a Typology of Risks (OECD, 2021) for children in the digital environment. There are content, conduct and contact risks as well as consumer risks. They identify cross-cutting risks as those that include all four of the risk categories. The three cross-cutting areas are Privacy Risks, Advanced Technology Risks, and Risks on Health and Wellbeing (OECD, 2021).

Recognizing that the teaching of digital privacy is a shared responsibility, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) (2022) has produced materials to encourage this shared responsibility. There is a graphic novel, Social Smarts: Nothing personal!, a downloadable resource in which a phone guides a student through the online world. It is aimed at youth 8-10 years old. In addition, the OPC co-sponsored a global resolution on children’s digital rights [PDF]. There is a highly informative blog post for parents entitled Having a Data Privacy Week ‘family tech talk’ with suggestions on how to protect child privacy and recommendations for how to have tech talks.

There have been other, international responses regarding the shared responsibility to keep children safe online. In the UK they have created a data protection code of practice (OPC, 2022), called the Age Appropriate Design Code, which requires internet companies to respect children’s rights, act in their best interest, and make products safer for children.

4. Framing digital privacy discussions for schools

There are some key considerations that can frame discussions about digital privacy in schools.

Duty of Care: Teachers and administrators have a duty of care under the Ontario Education Act that requires them to be positive role models for students and act as a kind, firm and judicious parent would act to protect them from harm. This standard of care varies depending on the type of activity and the age of the students. The younger and less experienced students would require closer supervision (Berryman, 1998). The protection of personally identifiable information (PII) for youth has a different level of importance because there are greater risks for their safety and their age may make them less able to give informed consent.

Policy Patchwork: First, educators need to be aware that they are operating in a policy forum that has multiple policy designers at different levels such as the school, educational authority or district level, provincial level and national level. For example, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has lessons for students in Grades 9-12 that are based on privacy principles from the Personal Information Protection Acts that guide Alberta and British Columbia, An Act Respecting the Protection of Personal Information in the Private Sector from Quebec, as well as PIPEDA (a national Act, described earlier in this chapter). The lesson is designed to teach students about their rights to privacy. It provides a self-assessment for students to understand how well they understand privacy and shows them how to make a privacy complaint.

Rights to privacy: Secondly, students need to be informed about the degree of surveillance operating somewhat unregulated at present and how this has implications for their safety as well as their right to information (e.g., news and websites) that has not been curated for them. If the provincial curriculum policies do not require students to learn about the protection of PII, the implications of their digital footprint and digital permanence, then school districts or authorities will need to find ways to address this gap. The curriculum should be based on the provision of information about the right to privacy, how students can take action to protect their personal information and their rights to recourse when they are being monitored or the information (news) they seek is being curated. For example, the PVNCCDSB, an Ontario school district, has developed a Digital Privacy Scope and Sequence from Kindergarten to Grade 12 that supports student privacy alongside the acquisition of digital skills. From the importance of using correct passwords to curating a digital footprint, students learn the skills with the instruction of

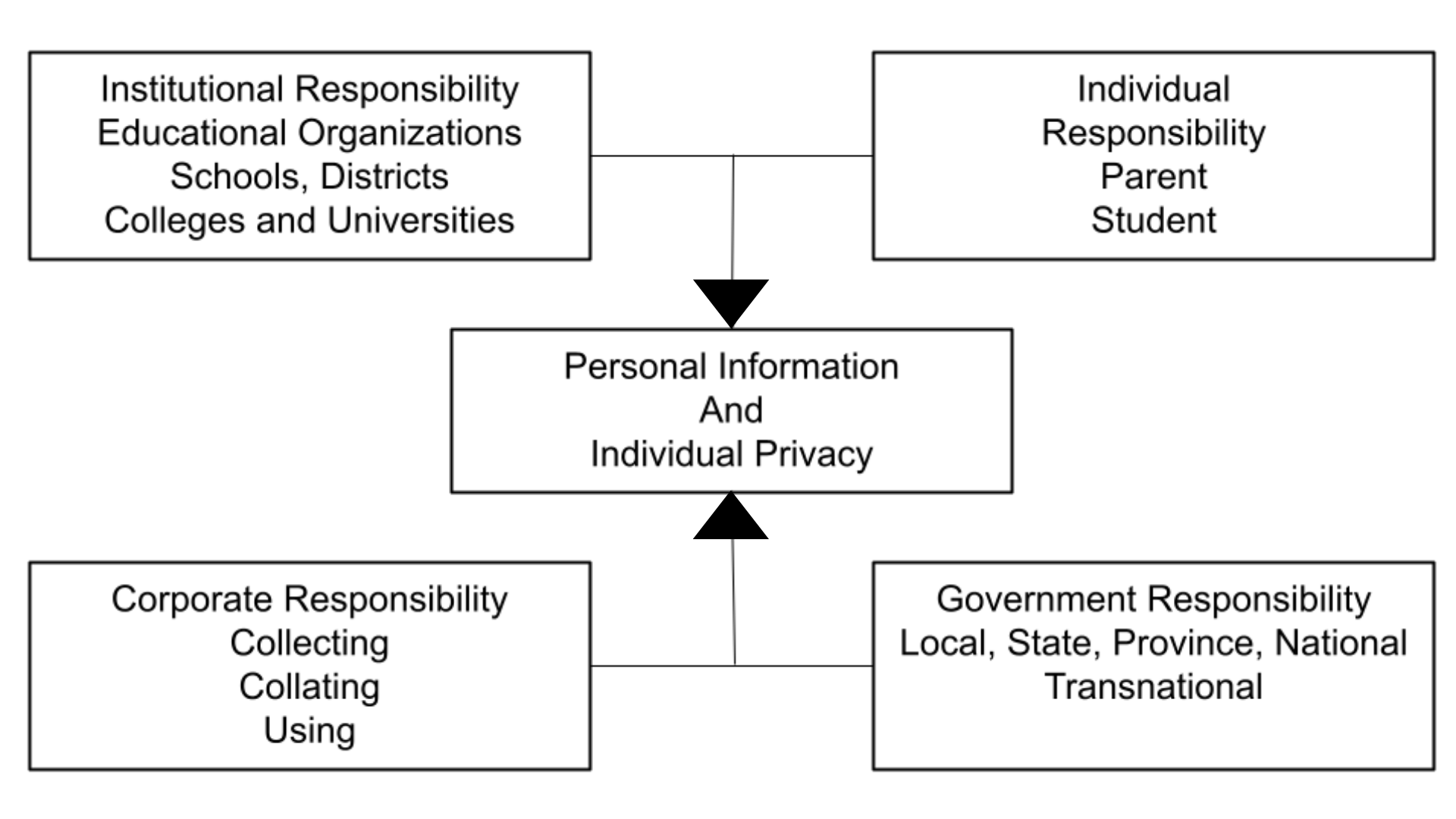

Shared responsibility: In this chapter, we have advocated that the protection of personal information and individual privacy is a shared responsibility. First of all, the educational institutions, such as the school districts or school authorities, the colleges and universities share an institutional responsibility to create policies that are clear and understood by their students. Corporations that use data for marketing purposes need to be more transparent about how they collect data and provide easy opt-out solutions. Governments have the responsibility to create digital privacy policies that protect citizens from corporate profit and overreach. Finally, individuals, parents, students and educators have the responsibility to educate themselves on the topic of digital privacy.

Figure 2.

The International Competency Framework for Privacy Education

A consortium of international data protection commissioners wrote a framework for teaching about data protection, the International Competency Framework on Privacy Education. Their intent was not to put the responsibility for teaching about data protection on the schools, but they wanted to share their expertise by developing a framework of digital competencies (International Working Group on Digital Education, (IWG), 2016).

The commissioners did not match the framework to specific legislation but designed the competencies so that they would function irrespective of jurisdiction. Their goal was to create an international base of common knowledge and skills on digital privacy for education and distribute this information for the benefit of students and schools. This framework focuses on empowering the digital student and encourages them to work with a responsible adult. It takes into consideration research that youth do care about their privacy (e.g., Palfrey et al., 2010) and that they need to work together with concerned adults such as their parents and teachers to build their skills in a digital era. (Robertson & Muirhead, 2020).

Here is a summary of the nine guiding principles in this International data competency framework:

- Students should understand the concept of personal data. They should know that personal data is any data that identifies an individual. Students should learn how to discern which information is particularly sensitive, something which can vary from country to country. They also need to know how their online presence can be traced back using technical data and metadata.

- Students should understand that privacy is a human right that should be protected. They need to know how their actions can affect their own privacy and the privacy of others.

- Students need to understand the digital environment’s technical aspects and how digital space is structured. This includes an understanding of the risks associated with the digital space and what is meant by digital security. Students should also learn how to ensure the security of their own digital environment.

- Students should understand the digital economy of service providers and terms of use. They need to know the key players in the digital environment, and how personal user preference files are established. Student users need to know what data is collected and stored while online.

- The fifth principle is the understanding that there are some key rules which are important for data protection, such as people’s rights to be informed about who is collecting their personal information, for what purpose, and how long data will be stored. End users also need to know how to work with data protection authorities.

- Students should understand key aspects of personal data regulations and the necessity to manage the use of personal information. Students should learn how to investigate the nature of the space where they are sharing information and monitor the content and information about them that exists online. Also, students should be taught to participate online in ways that respect other people, including not sharing others’ information without their consent.

- Students should understand how to regulate the use of personal information. This seventh principle is about encouraging students to seek the consent of parents or a responsible adult, and know that they can refuse collections of personal data and monitor the information about them located online.

- Students should be aware of their rights to delete information and control access to their information. The eighth principle focuses on students’ rights to use technology to protect and secure their data. Examples include managing their settings and refusing geolocation, for example.

- Students should develop critical and ethical digital citizenship skills. The final (ninth) principle is one of digital citizenship which includes learning to assess the reliability and credibility of information and identifying inappropriate or illegal content (IWG, 2016).

The Last Word—A Critical Stance

We encourage educators who are reading this chapter to discuss their level of comfort with the types of surveillance of youth and adolescents that seem increasingly similar to the surveillance methods used by the police in crime shows on television. Educators need to step back and consider carefully their level of comfort with presentations at schools that imply that parents are not capable or are too busy to help their children and adolescents discern safe and unsafe online spaces. While we would not question a specific type of internet surveillance tool that is available to parents, we have questions about whether or not it is a good idea for parents to receive daily copies of young people’s online transactions. We also want to raise questions about the rights of surveillance organizations to out students before they are ready to disclose their sexual orientation or gender preference to their families. We encourage educators not to accept forms of surveillance and curation of content uncritically.

Secondly, we find that there are holes in the protection net for students and teachers surrounding digital privacy. Teachers are encouraged by the pamphlets from the Information and Privacy Commissioner to gain consent before posting students’ pictures and they are reminded to follow school district policies (Information & Privacy Commission, 2019). These guidelines, however, lack the specifics and the understandings implicit in the GPEN International Working Group Digital Education competencies (IWG, 2016) in areas such as digital permanence, digital footprint and the potential impact of data (re)combination on privacy and choice.

References

Accepting Schools Act, 2012, S.O. 2012, c. 5 – Bill 13. (2012, June 19). Chapter 5: An act to amend the education act with respect to bullying and other matters. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/s12005

Akyurt, E. (2020, March 30). In a gray sweater on a laptop facemask [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/hkd1xxzyQKw

Berryman, J. H. (1998, December). Duty of care. Professionally Speaking, 1998(4). https://professionallyspeaking.oct.ca/december_1998/duty.htm

Bourdages, G. (2017, December 11). Person in front of red lights [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/WDbuusPOnkM

Boyd, D., Hargittai, E., Schultz, J., & Palfrey, J. (2011). Why parents help their children lie to Facebook about age: Unintended consequences of the ‘Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act.’ First Monday, 16(11), Article 3850. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v16i11.3850

Bradshaw, S., Harris, K., & Zeifman, H. (2013, July 22). Big data, big responsibilities: Recommendations to the office of the privacy commissioner on Canadian privacy rights in a digital age. CIGI Junior Fellows Policy Brief, 8, 1-9. https://www.cigionline.org/publications/big-data-big-responsibilities-recommendations-office-privacy-commissioner-canadian

Chen, B. (2015). Exploring the digital divide: The use of digital technologies in Ontario Public Schools. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology / La Revue Canadienne De l’Apprentissage Et De La Technologie, 41(3), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.21432/T2KP6F

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998, 15 USC §6501: Definitions. (1998, October 21). http://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid%3AUSC-prelim-title15-section6501&edition=prelim

Dangerfield, K. (2018, March 28). Facebook, Google and others are tracking you. Here’s how to stop targeted ads. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/4110311/how-to-stop-targeted-ads-facebook-googlebrowser

Electronic Privacy Information Center. (n.d.). California S.B. 27, “Shine the Light” Law. https://epic.org/privacy/profiling/sb27.html

Feathers, T. (2019, December 4). Schools spy on kids to prevent shootings, but there’s no evidence it works. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/8xwze4/schools-are-using-spyware-to-prevent-shootingsbut-theres-no-evidence-it-works

Federal Communications Commission. (2019, December 30). Children’s internet protection act (CIPA). https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/childrens-internet-protection-act

Fisk, N. W. (2016). Framing internet safety – the governance of youth online. MIT Press Ltd.

Flaherty, D. H. (2008, June). Reflections on reform of the federal privacy act. Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy-topics/privacy-laws-in-canada/the-privacy-act/pa_r/pa_ref_df/

Geary, J. (2012, April 23). DoubleClick (Google): What is it and what does it do?. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2012/apr/23/doubleclick-tracking-trackers-cookies-web-monitoring

Global Privacy Enforcement Network (GPEN). (2017, October). GPEN Sweep 2017: User controls over personal information. UK Information Commissioner’s Office. http://www.astrid-online.it/static/upload/2017/2017-gpen-sweep—international-report1.pdf

Government of Canada. (2019, June 21). Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). Justice Laws Website. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/P-8.6/index.html

Government of Canada. (2021, June 22). Canadian internet use survey, 2020. The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210622/dq210622b-eng.htm

Grant-Champan, H., Laird, E., Venzke, C. (2021, September 21). Student activity monitoring software: Research insights and recommendations. Center for Democracy and Technology. https://cdt.org/insights/student-activity-monitoring-software-research-insights-and-recommendations/

Hampson, R. (2017, December 29). Scrolling apps [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/cqFKhqv6Ong

Hankerson, D. L., Venzke, C., Laird, E., Grant-Chapman, H., & Thakur, D. (2022). Online and observed: Student privacy implications of school-issued devices and student activity monitoring software. Center for Democracy & Technology. https://cdt.org/insights/report-online-and-observed-student-privacy-implications-of-school-issued-devices-and-student-activity-monitoring-software/

Haskins, C. (2019, November 1). Gaggle knows everything about teens and kids in school. BuzzFeed. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/carolinehaskins1/gaggle-school-surveillance-technology-education

Hatmaker, T. (2021, July 7). Google faces a major multi-state antitrust lawsuit over google play fees. TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2021/07/07/google-state-lawsuit-android-attorneys-general/

Hermant, B. (2018). Free WiFi inside [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/X0EtNWqMnq8

Hill, K. (2016, March 31). How Target figured out a teen girl was pregnant before her father did. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2012/02/16/how-target-figured-out-a-teen-girl-was-pregnant-before-her-father-did/?sh=5c44383a6668

Information and Privacy Commission for Ontario (2019). Privacy and access to information in Ontario Schools: A guide for educators. https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/fs-edu-privacy_access-guide-for-educators.pdf

International Working Group on Digital Education (IWG). (2016, October). Personal data protection competency framework for school students. International Conference of Privacy and Data Protection Commissioners. http://globalprivacyassembly.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/International-Competency-Framework-for-school-students-on-data-protection-and-privacy.pdf

Levine, M. A. J. (2020, September 17). Troubling Clouds: Gaps affecting privacy protection in British Columbia’s K-12 education system. BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association. https://fipa.bc.ca/news-release-new-report-highlights-gaps-in-student-privacy-in-bcs-k-12-education-system/

Lohr, S. (2020, September 21). This deal helped turn Google into an ad powerhouse. Is that a problem?. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/21/technology/google-doubleclick-antitrust-ads.html

Madrigal, D. V. H., Venzke, C., Laird, E., Grant-Chapman, H., & Thakur, D. (2021, September 21). Online and observed: Student privacy implications of school-issued devices and student activity monitoring software. Center for Democracy & Technology. https://cdt.org/insights/report-online-and-observed-student-privacy-implications-of-school-issued-devices-and-student-activity-monitoring-software/

McLeod, J. (2020, June 12). Double-double tracking: How Tim Hortons knows where you sleep, work and vacation. Financial Post. https://financialpost.com/technology/tim-hortons-app-tracking-customers-intimate-data

Ministry of Education. (2020, August 13). Requirements for remote learning. Policy/Program Memorandum 164. https://www.ontario.ca/document/education-ontario-policy-and-program-direction/policyprogram-memorandum-164

Municipal Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (MFIPPA, R.S.O. 1990, c. M.56. (2021, April 19). Queen’s Printer for Ontario. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90m56

NASA. (2015, December 26). Connected world [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/Q1p7bh3SHj8

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2021, January). Children in the digital environment: Revised typology of risks. OECD Digital Economy Papers, 302, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1787/9b8f222e-en

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. (2021, August 13). Guidelines for obtaining meaningful consent. https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/privacy-topics/collecting-personal-information/consent/gl_omc_201805/#_seven

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (2022, January 24). Data privacy week: A good time to think about protecting children’s privacy online. https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/opc-news/news-and-announcements/2022/nr-c_220124/

Ohm, P. (2010, August). Broken promises of privacy: Responding to the surprising failure of anonymization. UCLA Law Review, 57, 1701-1777. https://www.uclalawreview.org/pdf/57-6-3.pdf

Palfrey, J., Gasser, U., & Boyd, D. (2010, February 24). Response to FCC notice of inquiry 09-94: “Empowering parents and protecting children in an evolving media landscape.” Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. https://cyber.harvard.edu/sites/cyber.law.harvard.edu

/files/Palfrey_Gasser_boyd_response_to_FCC_NOI_09-94_Feb2010.pdf

Robertson, L., & Corrigan, L. (2018). Do you know where your students are? Digital supervision policy in Ontario schools. Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, 16(2), 36-42. http://www.iiisci.org/journal/PDV/sci/pdfs/HB347PG18.pdf

Robertson, L., & Muirhead, W. J. (2020). Digital privacy in the mainstream of education. Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, 16(2), 118-125. http://www.iiisci.org/journal/pdv/sci/pdfs/IP099LL20.pdf

Solove, D. J. (2004). Digital Person: Technology and privacy in the information age. New York University Press. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2501&context=faculty_publications

Spiske, M. (2018, May 15). Green binary code [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/iar-afB0QQw

Steeves, V. (2014). Young Canadians in a wired world, phase III: Life online. MediaSmarts. http://mediasmarts.ca/sites/mediasmarts/files/pdfs/publication-report/full/YCWWIII_Life_Online_FullReport.pdf

Sweeney, L. (2004), Simple demographics often identify people uniquely. Carnegie Mellon University, Data Privacy Working Paper 3. Pittsburgh 2000. https://dataprivacylab.org/projects/identifiability/paper1.pdf

Telford, H. (2017, October 29). Opinion: Public schools ask parents to sign away children’s privacy rights. Vancouver Sun. https://vancouversun.com/opinion/op-ed/opinion-public-schools-ask-parents-to-sign-away-childrens-privacy-rights/

Thompson, S. A., & Warzel. (2019, December 19). Twelve Million phones, one dataset, zero privacy. The New York Times: The Privacy Project. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/19/opinion/location-tracking-cell-phone.html

Tullius, T. (2020, May 30). A painting on a wall warning visitors about video surveillance [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/4dKy7d3lkKM

van Zoonen, L. (2016). Privacy concerns in smart cities. Government Information Quarterly, 33(3), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.06.004

Venzke, C., & Laird, E. (2021, September 21). CDT and Coalition of Education and civil rights advocates urge Congress to protect student privacy. Center for Democracy & Technology. https://cdt.org/insights/cdt-and-coalition-of-education-and-civil-rights-advocates-urge-congress-to-protect-student-privacy/

Wojcicki, S. (2009, March 11). Making ads more interesting. Google Official Blog. https://googleblog.blogspot.com/2009/03/making-ads-more-interesting.html

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the New Frontier of Power. Public Affairs.

Zuboff, S. (2020, June 24). You are now remotely controlled: Surveillance capitalists control the science, and the scientists, the secrets and the truth. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/24/opinion/sunday/surveillance-capitalism.html