6 The Privacy Paradox: Present and Future

Lorayne Robertson

This chapter will assist students to be able to:

- Understand how research has informed current understandings of the privacy paradox.

- Explain how research is informing policy designers for ways to address the privacy paradox, including privacy by design.

- Apply understandings from this chapter to educate others on the implications of the privacy paradox and the need for privacy by design.

Defining the Privacy Paradox

| A paradox is a logically self-contradictory statement or a statement that runs contrary to one’s expectation. It is a statement that, despite apparently valid reasoning from true premises, leads to a seemingly self-contradictory or a logically unacceptable conclusion.

(Wikipedia, 2022) |

The privacy paradox is a conceptual model that attempts to capture the trade-off between convenience and privacy. While studies indicate that people want to guard their personal information closely (Antón et al., 2010), the ease with which customers can bypass the terms of service (TOS) or privacy policies in online applications is part of the puzzle of privacy protection in the digital age that challenges research to establish its contributing factors. It is in the best interest of the economy to maintain consumer trust in online commerce by protecting digital privacy.

At times, it appears that innovation is eroding the protection of privacy. Increasingly, one can argue that the ability NOT to be tracked or observed today is elusive. There is surveillance tracking shopping in stores, observing the patterns that shoppers take in the stores and their choices as consumers. Many new applications are designed to provide a service but simultaneously erode solitude and privacy through tracking mechanisms. Vehicles and devices have GPS trackers; wearables track fitness levels, activities and location. The Internet of things (IoT), which includes home appliances, tracks and exchanges personal data about the lives of persons in the home. While people are on mobile devices constantly communicating with each other, online services are tracking them. Given this level of surveillance, one could not blame the average citizen if they concluded that loss of privacy is inevitable. It may also be the case, however, that given the overall digital privacy picture in Canada, privacy protection policies and TOS are poorly understood and under-subscribed to by the users and deliberately not explained well by the vendors.

One contribution to the general erosion of privacy are trends such as is the significant increase in online professional and social networking. At times, participation in professional sites that share information about your personhood is encouraged by employers. According to Antón et al. (2010), LinkedIn, for example, garnered some 33 million users, just in its first five years. Facebook, which is a global social networking site, had 2.9 billion users at the close of 2021 (Statista.com). The global pandemic also contributed by moving much of Canadian retail online. Online shopping is very popular in Canada with more than 28.1 million Canadians making purchases online and a reported 3.3 billion Canadian dollars in monthly retail e-commerce sales (Coppola, 2022). Many of these sites require customers to provide their email, allowing the retailer to tailor and personalize advertising to them.

At the same time, unconnected to commercial use, newer technologies are emerging that have privacy implications. One example is body-worn cameras employed by police services, designed to protect both the public and the officers yet they also surveil the general public. Another recent innovation is virtual health care. There has been a proliferation of apps provided recently where patients can download and track their health history from the hospital or check the results of their latest tests online. In addition, since the onset of the pandemic, virtual health care visits have become the norm. In Ontario, there is an online health service that provides medical advice 24/7. Each of these emergent affordances should be reviewed for the privacy and security risks that are associated with them, particularly in light of frequently-reported data breaches in other sectors.

While digital technologies offer more affordances than ever before, one of the risks connected to these affordances is privacy. In this chapter, we explore the digital privacy paradox which occurs when concerns about privacy are weighed against convenience. This paradox has not always existed—it is more of a development that has emerged over the past 15 years. Powell (2020) reports that Zuboff explained to the Harvard Gazette that only 1% of global information was digitized in 1986. By the year 2000, this had increased to 25 percent. By 2007, the amount of information digitized globally was 97% and this came to represent the tipping point. Today most information is digital (Powell, 2020). Table 1 provides some examples of the privacy paradox enacted in daily life and in education.

Table 1

Gains Versus Privacy Tradeoff

| Scenario | Gains | Tradeoff |

| It is 11 pm, and you are on the highway in an unfamiliar setting. You need a hotel, so you download a hotel cost comparison app. The privacy agreement is 17 pages long, so you click through to get to the app without reading the agreement. | Convenience, Safety, Shelter | Privacy |

| As a teacher, you need an app to provide visualization for a math lesson. It will not let you add a class list of pseudonyms to participate on the app. Every student has to provide their personal email or their parents’ email in order to join. | Providing the best educational experience possible | Students’ and parents’ private information may be compromised for third-party providers |

| As a parent, you hear that all students in the class are using a cloud-based data sharing app for writing schoolwork, but you have a concern that your child’s data will be in the cloud. | Your child needs to be connected in school and part of the class | Students’ and parents’ private information may be compromised for third-party providers |

| You want to collect points, so you download the loyalty app to your favourite coffee shop. | Loyalty rewards, they know your order, they prepare your order in advance | Privacy is compromised as this app and its related apps track your location constantly |

| Big data employs AI and algorithms to mine the data so that advertising can be targeted directly to a classification of customers who are in a similar demographic. This provides a competitive edge to the company and supports the digital economy | Personalized service, less time to load in the information each time | Your personal information is sold and shared with third parties, risk of privacy violations, breeches, identity theft |

Solove (2020) writes that the privacy paradox, which was identified more than 20 years ago as an “inconsistency between stated privacy attitudes and people’s behaviour” (p. 4) is not a paradox but is, instead, an illusion and a myth. He sees futility in the concept of privacy self-management, and he states,

Managing one’s privacy is a vast, complex, and never-ending project that does not scale; it becomes virtually impossible to do comprehensively. The best people can do is manage their privacy haphazardly. People can’t learn enough about privacy risks to make informed decisions about their privacy. (p.3)

Further, Solove (2020) explores various studies that have established evidence of the paradox between people’s intentions online and their actions. He acknowledges the role that technology has played in designing consent stating,

The Internet makes it easier for people to share information without the normal elements that can make them fully comprehend the consequences. If people were put in a packed auditorium, would they say the same things they say online? Most likely not. When people post online, they don’t see hundreds of faces staring at them. (p. 15)

Solove recommends that privacy regulation should be strengthened so that the laws do not rely on individuals managing their own privacy. His argument is that privacy regulation, “should focus on regulating the architecture that structures the way information is used, maintained, and transferred” (Solove, 2020, p. 3).

In the section that follows, some of the emerging research on the privacy paradox is outlined, providing more insights on whether the most promising solutions are leaning toward increased legislation or consumer empowerment.

Understanding the Privacy Paradox

Recognizing that the privacy paradox is an established construct, one approach would be to look for solutions to address it or change aspects of it so that there is more compliance and less of a paradox. Some might look for top-down approaches to protect digital privacy, in the form of stronger or more specific policy (laws and legislation); others might seek bottom-up solutions that educate the consumer and encourage them to exercise care to protect their privacy. There is general agreement that fair information practices should offer notice to inform users when information is being collected and for what purpose; and choice about whether or not the information is shared (See PIPEDA in Chapter 2.). There is also a recognition that the TOS are generally not that helpful in protecting privacy (e.g., Awad & Krishnan, 2006; Massara et al., 2020).

Researchers disagree on the approach forward. The approach that some researchers have taken is to investigate consumers’ choices and thought processes when faced with TOS or a privacy policy in order to download or use an application. What has emerged in the flurry of research surrounding digital privacy in the present era, is the understanding that the privacy paradox is not unidimensional, and there are multiple factors to be considered.

Obar and Aeldorf-Hirsch (2018) claim that the clickthrough agreement (they call this clickwrap) discourages and thwarts the critical inquiry that is central to deciding notice and choice; this results in supporting business. They define clickwrap as,

A digital prompt that enables the user to provide or withhold their consent to a policy or set of policies by clicking a button, checking a box, or completing some other digitally mediated action suggesting “I agree” or “I don’t agree.” (p.3)

The policies may not be written out, instead, there may be a link to the privacy policies or TOS. In other words, a clickthrough policy appears to be deliberately designed to discourage more critical choices. They theorize that, while the length and complexity of policies impact user engagement with them, this “does not tell the whole story” (p. 3). One factor may be resignation that the consumer is powerless to make substantive changes. A more deliberate strategy suggested is that social media takes advantage of the clickthrough in order to connect users to social media services as quickly as possible in order to monetize their involvement as quickly as possible. Advertisers want to avoid controversy, disagreement and critical review of the policies in order to keep consumers in a “buying mood” (p. 6). Other factors may come into play, such as using the smaller icons for the privacy policy or other similar efforts to discourage users to engage in the consent process fully (Obar & Aeldorf-Hirsch, 2018).

Obar and Oeldorf-Hirsch (2020) asked adults to join a fictitious social networking site. They observed how the digital clients approached the privacy policies and TOS agreements. The result was that 74% skipped the privacy policy using the clickthrough option. If they did not select the clickthrough option and read the privacy policy, the average reading time spent on the privacy policy was 73 seconds. Most (97%) agreed to the privacy policy. In a surprising finding, 93% agreed to the TOS even though the TOS had gotcha clauses indicating that data would be shared with the NSA and participants would provide their first-born child as payment. The researchers concluded that information overload is a significant negative predictor for skimming rather than reading the TOS, and participants view policies as a nuisance” (Obar & Aeldorf-Hirsch, 2020).

Wang et al. (2021) see the paradox as the competing interests of the economic realities of the need for big data to support e-commerce and the privacy needs of individuals, (which they see as a psychological need). They explore an additional paradox, which is the one between attitudes toward privacy and privacy-protective behaviours. Their research indicates that online users also have peer privacy concerns, which they describe as “the general feeling of being unable to maintain functional personal boundaries in online activities as a result of the behaviours of online peers” (p. 544).

Another privacy paradox explained by Massara et al. (2021) is that, while Europeans indicated that they were concerned about privacy, it seemed that it would follow that consumers would not choose Google and Facebook, who had been sanctioned for privacy violations. The paradox was that, instead of discouraging online participants when violations occurred, the Google search engine had a 90% market share in Europe. The reported results were similar for YouTube and Facebook in the US. As a result, Massara et al. (2021) investigated whether consumer consciousness of the risks associated with digital privacy would be sufficient to change their behaviours.

Massara et al. (2021) find that perception of risk is unlikely to impact consumer consent. What is more likely to impact consent to disclosure are the perceived benefits and familiarity with the site or organization collecting the data. More importantly, Massara and colleagues’ research shows that “the privacy paradox is not a monolithic construct but one that is composed of several possible facets” (p. 1821). This research team concludes that the relevance of the variables they have identified regarding consent suggests that companies should facilitate tools for customer choice and facilitate the empowerment of consumers to make informed decisions—even helping consumers to understand the impact of their choices. They recommend the kind of protections established in Europe such as providing limits on data processing, allowing for the withdrawal of consent and also what is known as the right to be forgotten in the European privacy legislation (Massara et al., 2021). They find that this matches Solove’s (2020) argument that people make decisions about risk in specific contexts while their views about privacy are more general.

At this point in time, there are arguments both for top-down solutions through policies and for bottom-up solutions aimed at increasing consumer empowerment for digital privacy choices. When engaging with European online publishers recently, this author has noted that the right to consent to cookies is explained clearly on their website. The user has clear choices and buttons to click with respect to choices surrounding disclosure of information, consent to be on an email list, or disclosure of personal information to third parties. This level of consumer clarity for notice and choice, if practiced more generally, has the potential to erode the perception of a privacy paradox.

The Privacy Paradox in Education

| The paradox of privacy occurs when security is weighed against convenience. We consider this paradox in light of the increasing use of technology by teachers and school districts.

(Robertson & Muirhead, 2019) |

There is a growing awareness that technology is helpful to students (Pierce & Cleary, 2016). European research shows that the use of technology in schools benefits student learning, impacts student motivation in a positive way, promotes more student-centred learning and increases the number of teaching and learning strategies used. There is also growing awareness that Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) are helpful to students in schools (Balanskat et al., 2006). Similarly, the American government notes that technology use in education increases tools for learning, expands course offerings, accelerates student learning and also increases motivation and engagement (US Department of Education, n.d.). Some research notes a positive impact on student learning outcomes (Greaves et al., 2012).

While the cost of equipment negatively impacted the growth of technology use in schools, gradually schools introduced laptops and more portable devices into classrooms. When wireless technology became available, and bandwidth sufficiency issues were resolved, technology use in schools increased (Ahlfeld, 2017; Pierce & Cleary, 2016). As more research becomes available about increases in the use of technology during the pandemic, it will undoubtedly report an increase in the use of technology during emergency remote learning and similar shutdowns of in-person schooling. While internet usage continues to increase, the reality is that two-thirds of the children in the world do not have internet access at home (UNICEF, 2020) which has significantly impacted their education during the school closures from the pandemic. Similarly, 63% of youths ages 15-24 lack internet access globally (UNICEF, 2020).

In Canada, there is a different picture where 99% of Canadian students surveyed in one study have internet access (Steeves, 2014). Against this backdrop of ever-increasing online participation, digital privacy concerns emerge. Students and teachers who may employ click-through agreements to share their personal information may not be aware that they are leaving a digital footprint and that their information is tracked for purposes of creating lists to personalize the advertising and the news feeds that they receive. Students and teachers may not be aware that they are creating a digital dossier that provides data about themselves and their friends. Adults who supervise them may not know that these digital dossiers can be sold without alerting end-users (Robertson et al., 2018) and that their online data has permanence. One issue is that youth may not be aware that their personal information is for sale. They may not be aware until there are consequences such as a denial of an application for work or for a loan.

The Privacy Paradox in the Age of Covid

Schools have increasingly turned to large corporations to provide the Learning Management Systems, internal email and search engines to power students’ learning. The advent of Chromebooks was a game-changer because students could work in the cloud and users could image their own devices. Within education, some research has indicated that teachers care about privacy, but they are also not aware of how to protect student privacy or how to encourage students to protect their privacy (Leatham, 2017; Leatham & Robertson, 2017).

During the period of emergency remote learning, where the pandemic resulted in rapid, emergency health decisions, government agents and school districts made decisions rapidly without consulting on the privacy aspects. For example, in Ontario, teachers were required to provide synchronous, online learning or hybrid learning, and there was insufficient time to research the privacy implications of young children appearing on the screens and showing their understanding of school-led learning with others watching. There are even risks for adults; Abrams (2020) reports that a hacker leaked the data from sites such as ProctorU, compromising the data of almost half a million participants. The abrupt shift to emergency online teaching has led to the purchase of outsourced applications before there was time to protect for privacy concerns. This emergency teaching may have led to the purchase of outsourced applications without comprehensive testing for privacy concerns. Germain (2020) describes the concern of a Canadian student who had to allow the scan of her face as well as her bedroom in order to take a test for her course at a Canadian University. Similarly, Abrams (2020) reports that a hacker released the data files at ProctorU which compromised the data of more than half a million test-takers. There were also concerns about equity issues for the proctoring services which were broadband width sensitive and involved persons watching students in their homes, leading to the Consumer Reports investigation (Germain, 2020).

Recognizing that Canadian children and youth are spending an increasing amount of time online both for socializing and for school purposes during the pandemic, Daniel Therrien, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (Office of the Privacy Commissioner, 2022) co-sponsored a resolution on children’s digital rights [PDF] that recognizes that the digital world provides opportunities to children but also can infringe on their rights such as the right to privacy. This global resolution affirms that the information posted about children can be collected and used by third parties and that those collecting data have a responsibility toward minors. The resolution stresses that children are particularly vulnerable and that children’s online privacy is a priority. To that end, the resolution notes the need to raise awareness among caregivers and educators of the online commercial practices that could harm minors.

Robertson and Muirhead (2019) in describing the context for the digital privacy paradox in schools state,

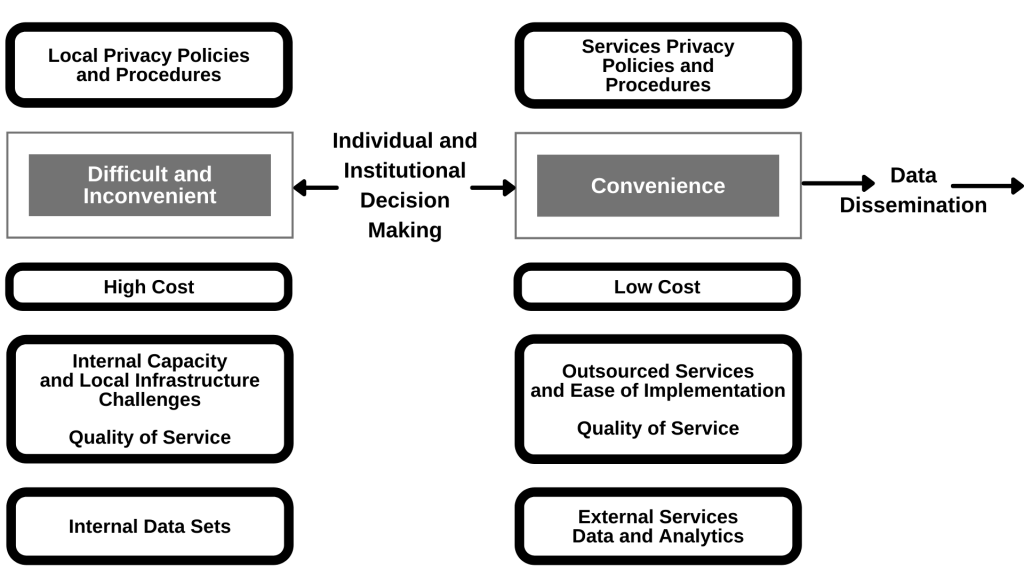

Privacy is often understood in terms of applications, infrastructure and risk associated with the use or unintended use of personal data. This orientation to “risk as the loss of data” omits decisions about what technologies, services and personal choices including beliefs, inform decisions made by individuals, groups or institutional services that collect data. While services are often seen as software and applications, increasingly, corporations are developing hybrid infrastructures that bundle services with specific hardware such as Google with Chrome Books and a G-Suite of applications for schools and students, or Apple with Ipads and iCloud or Amazon with their set of learning solutions including Amazon-Inspire, LMS and Amazon AWS (web services that run Cloud applications). (p. 31)

Robertson and Muirhead (2019) developed a framework for educational decisions that acknowledge the paradox between ease of use and decisions required for education. Recent data breaches and intrusions into corporate accounts have established some risks inherent in online participation and the erosion of trust concerning the external collection of personal data.

Figure 1.

Education and the Privacy Paradox

Privacy by Design

Dr. Ann Cavoukian, who was the Information and Privacy Commissioner for Ontario for three terms (17 years) created Privacy by Design and its 7 Foundational Principles (Cavoukian, 2011). There are seven principles in the concept of Privacy by Design and each one is just as important as the next. These principles are:

- Proactive not Reactive/Preventative not Remedial.

- Privacy as the Default.

- Privacy Embedded into Design.

- Full Functionality.

- End-to-End Security.

- Visibility and Transparency.

- Respect for User Privacy.

Cavoukian (2019) in an interview compares Privacy by Design to a medical model that is interested in prevention before a privacy breach occurs. In her view, good privacy models promote creativity and it is in the best interest of businesses to promote good security models. Based on her experience, she advocates for a global framework of good privacy practices that include data portability (meaning that the customer can move personal data from one business to another) and the right to be forgotten. She advocates that having privacy protected should be the default box in online choice—the app should give privacy automatically. This would take the onus off the user to protect their privacy. She sees benefits for business in following the seven principles. If businesses tell customers what they are doing and are transparent with them, a trusting relationship is more likely to develop and customers will be more likely to stay with the vendor.

Cavoukian (2019) also discusses how some of the current privacy risks have been created through newer devices that she describes as, not ready for prime time in her interview. Examples include digital assistants that listen in and broadcast personal conversations and the capture of mobile phone conversations with devices used by law enforcement such as the StingRay device; here the regulations to protect digital privacy have not caught up with the technology (Brend, 2016).

The future of digital privacy as Couvukian sees it, is one where data becomes more decentralized and moves away from the big data model. She provides the example of a Toronto waterfront development proposal where the designers intend to de-identify the data as it is collected. She argues that the technology is already there for this trend to be realized, and it presents multiple wins for all of the stakeholders.

With respect to education, Couvukian (2019) advises that schools should help students, especially young students, understand what information can be shared to collaborate and what information should not be shared.

Some Final Thoughts on the Privacy Paradox

A report that was designed to restore confidence in Canada’s privacy regime (Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, 2017) reminds Canadians that we need to find ways to protect privacy online in order to allow the economy to grow and to allow Canadians to benefit from innovation. This national report provides risk abatement solutions through compliance with policies and educating users of technology. The report recommends that students should learn about privacy early and learn how to anonymize their personal information. When considered alongside the recommendations of the International Working Group (2016) and the Privacy by Design directions (Couvukain, 2011), there is the beginning of a roadmap for curriculum policies aimed at educating educational institutions.

In 2011, Jennifer Stoddard, then the Privacy Commissioner for Canada, recommended that corporations should collect only the minimum amount of personal information required, and they should provide clear unambiguous information about how the personal information would be used. It was also advised that consumers should be provided with easy-to-manage privacy controls and the means to delete their accounts. Despite these recommendations, the privacy paradox persists although new directions for building trust in Canadian online commerce have led to the creation of this placemat of forward directions (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2018).

Canada’s Digital Charter outlines that modernized consent should ensure that there is plain language so that people can make meaningful choices about consent to share information. Canadians should also be allowed to withdraw consent and request that individuals dispose of their personal information. Businesses would need to be transparent about how they make recommendations or referrals to individuals and businesses would have to explain how the information was obtained. There should also be clearer guidelines with respect to the protection of individual information.

In the US, new legislation requires the US Department of Homeland Security to conduct a study on K-12 cybersecurity risks (Bradley, 2021). This legislation reportedly is a starting point for establishing national K-12 cybersecurity standards.

The answers to the privacy paradox likely reside in a combination of considerations that include:

- limits on corporations similar to European approaches;

- an appreciation of the trust that can be built for users through privacy by design;

- newer technologies to de-identify data on capture;

- more education for the end-users, including students, parents and teachers;

- an appreciation of the complexity of the privacy paradox; and

- global recognition that privacy is a human right.

For the present, schools and parents need to help students understand that their online presence is permanent. Globally, citizens need to learn that their privacy has value and that their actions can put their own privacy and that of others at risk.

References

Abrams, L. (2020, August 9). ProctorU confirms data breach after database leaked online. BleepingComputer. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/proctoru-confirms-data-breach-after-database-leaked-online/

Ahlfeld, K. (2017) Device-driven research: The impact of Chromebooks in American schools. International Information & Library Review, 49(4), 285-289 https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2017.1383756

Antón, A. I., Earp, J. B., & Young, J. D. (2010). How internet users’ privacy concerns have evolved since 2002. IEEE Security & Privacy, 8(1), 21-27. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2010.38

Awad, N. F., & Krishnan, M. S. (2006). The personalization privacy paradox: An empirical evaluation of information transparency and the willingness to be profiled online for personalization. MIS Quarterly, 30(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148715

Balanskat, A., Blamire, R., & Kefala, S. (2006, December 11). The ICT impact report: A review of studies of ICT impact on schools in Europe. European Schoolnet. http://colccti.colfinder.org/sites/default/files/ict_impact_report_0.pdf

Bradley, B. (2021, October 8). New law requires Federal Government to identify K-12 cyber risks, solutions. EdWeek Market Brief. https://marketbrief.edweek.org/marketplace-k-12/new-law-requires-federal-government-identify-k-12-cyber-risks-solutions/

Brend, Y. (2016, August 9). Vancouver police admit using StingRay cellphone surveillance, BCCLA says. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/vancouver-police-stingray-use-cellphone-tracking-civil-liberties-1.3713042

Cavoukian, A. (2011). Privacy by Design: The 7 foundational principles. Privacy by Design. https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/resources/7foundationalprinciples.pdf

Cavoukain, A. (2019, June 27). Dr. Ann Cavoukian: Privacy by design, security by design. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqreZlGL8Dk

CDC. (2020, March 13). Virus [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/k0KRNtqcjfw

Coppola, D. (2022, January 11). E-commerce in Canada – statistics & facts. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/2728/e-commerce-in-canada/

Germain, (2020, December 10). Poor security at online proctoring companies may have put student data at risk. Consumer Reports. https://www.consumerreports.org/digital-security/poor-security-at-online-proctoring-company-proctortrack-may-have-put-student-data-at-risk-a8711230545/

Greaves, T. W., Hayes, J., Wilson, L., Gielniak, M., & Peterson, E. L. (2012). Revolutionizing education through technology: The project RED roadmap for transformation. International Society for Technology in Education.

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. (2018). Canada’s Digital Charter: Trust in a digital world [Graphic]. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/062.nsf/vwapj/1020_04_19-Website_Placemat_v09.pdf/$file/1020_04_19-Website_Placemat_v09.pdf

International Working Group on Digital Education (IWG). (2016, October). Personal data protection competency framework for school students. International Conference of Privacy and Data Protection Commissioners. http://globalprivacyassembly.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/International-Competency-Framework-for-school-students-on-data-protection-and-privacy.pdf

Kienle, L. (2020, November 30). Cable connection [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/j48IJb5oB4k

Leatham, H. (2017). Digital privacy in the classroom: An analysis of the intent and realization of Ontario policy in context [Master’s dissertation, Ontario Tech University]. Mirage. http://hdl.handle.net/10155/816

Leatham, H., & Robertson, L. (2017). Student digital privacy in classrooms: Teachers in the cross-currents of technology imperatives. International Journal for Digital Society (IJDS), 8(3). https://doi.org/10.20533/ijds.2040.2570.2017.0155

Massara, F., Raggiotto, F., & Voss, W. G. (2021). Unpacking the privacy paradox of consumers: A psychological perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 38(10), 1814-1827. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21524

Miske, I. (2017, February 13). Home shopping [Photograph]. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/Px3iBXV-4TU

Obar, J. A., & Oeldorf-Hirsch, A. (2018). The clickwrap: A political economic mechanism for manufacturing consent on social media. Social Media + Society, 4(3), Article 2056305118784770. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2056305118784770

Obar, J. A., & Oeldorf-Hirsch, A. (2020). The biggest lie on the internet: Ignoring the privacy policies and terms of service policies of social networking services. Information, Communication & Society, 23(1), 128-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1486870

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (2022, January 24). Data Privacy Week a good time to think about protecting children’s privacy online. https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/opc-news/news-and-announcements/2022/nr-c_220124/

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) (2017). 2016-17 Annual Report to Parliament on the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Privacy Act. Real fears, real solutions: A plan for restoring confidence in Canada’s privacy regime. https://www.priv.gc.ca/media/4586/opc-ar-2016-2017_eng-final.pdf

Pierce, G. L., & Cleary, P. F. (2014). The K-12 educational technology value chain: Apps for kids, tools for teachers and levers for reform. Education and Information Technologies, 21, 863-880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-014-9357-1

Powell, A. (2020). An awakening over data privacy. The Harvard Gazette. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/02/surveillance-capitalism-author-sees-data-privacy-awakening/

Prostock-Studio. (2020, July 24). Digital thoughts [Photograph]. Canva. https://www.canva.com/media/MAEC-U8QkYA

Robertson, L., Muirhead, B. & Leatham, H. (2018). Protecting students online: International perspectives and policies on the protection of students’ digital privacy in the networked classroom setting. In, 12th International Technology, Education and Development (INTED) conference. Valencia, Spain, March 5-7, 2018 (pp. 3669-3678). https://doi.org/10.21125/inted.2018.0705

Robertson L., Muirhead B. (2019). Unpacking the Privacy Paradox for Education. In A. Visvizi & M. D. Lytras (Eds), RIIFORUM: The international research & innovation forum: Research & innovation forum 2019, technology, innovation, education, and their social impact. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30809-4_3

Solove, D. J. (2020). The myth of the privacy paradox. George Washington Law Faculty Publications & Other Works. https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications/1482/

Statista Research Department. (2022, Feb. 14). Facebook: number of monthly active users worldwide 2008-2021. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/

Steeves, V. (2014). Young Canadians in a wired world, Phase III: Life online. MediaSmarts. http://mediasmarts.ca/sites/mediasmarts/files/pdfs/publication-report/full/YCWWIII_Life_Online_FullReport.pdf

Stoddart, J. (2011). Privacy in the era of social networking: Legal obligations of social media sites. Saskatchewan Law Review, 74, 263-274. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/sasklr74&div=20&id=&page=

UNICEF. (December 1, 2020). Two thirds of the world’s school-age children have no internet access at home, new UNICEF-ITU report says. UNICEF United Kingdom. https://www.unicef.org.uk/press-releases/two-thirds-of-the-worlds-school-age-children-have-no-internet-access-at-home-new-unicef-itu-report-says/

US Department of Education (n.d.) Use of technology in teaching and learning. Office of Elementary & Secondary Education. https://oese.ed.gov/archived/oii/use-of-technology-in-teaching-and-learning/

Wang, C., Zhang, N., & Wang, C. (2021). Managing privacy in the digital economy. Fundamental Research, 1(5), 543-551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2021.08.009

Wikipedia contributors. (2022, February 8). Paradox. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Paradox&oldid=1070583071