Unit 3 – Part 2 – History of Reasoning

History of Reasoning

There are a number of justifications to approach any discipline by reviewing history. First, it’s arrogant to assume that this instance of a critical thinking course, or my modern view of the practice of critical thinking is the first, or first one-thousandth in history. Humans have been around for approximately 300,000 years, with some evidence of their capacity to reason for about 50,000 years. There are have been many, many humans, from all cultures, that have thought about, designed, discussed, and improved the practice of reasoning over many years.

In Unit 2, you reviewed a History of Thinking, albeit a brief and predominantly male view of that history, and you also considered a feminist point of view. In this unit, you are going to explore an even wider viewpoint related to Reasoning. You started out this unit with a Cultural Awareness questionnaire and you may begin to see places and spaces where you are less open-minded about cultural differences than you might have thought. The purpose of this questionnaire was to start you thinking about how much an influence your cultural experience (where, how, and by whom you were raised and educated) may have on what you believe you “know,” and whether or not you have practiced thinking critically about what you know.

The logical place to start with Reasoning (and logic is an important aspect of reason) might be with a definition of reason, and some of its associated processes. Wikipedia describes Reason (as a noun) the following way:

Reason is the capacity of consciously making sense of things, establishing and verifying facts, applying logic, and adapting or justifying practices, institutions and beliefs based on new or existing information. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, language, mathematics, and art and is normally considered to be a distinguishing ability possessed by humans. Reason, or an aspect of it, is sometimes referred to as rationality (Wikipedia, n.d.).

There are a few items that might be pulled out of that definition and explored further. For example, facts, logic, beliefs, information, and rationality may raise some questions for you and entice you to learn more by surfing the Internet for ideas about them (I encourage this behaviour).

Questions to consider:

Facts seems like a very simple concept, but as proposed at the start of this chapter, epistemology, a person’s worldview about what is “knowable and known,” can leave a lot of room for interpretation. What makes a fact, a fact?

The practices of logic and argument play some part in transforming information into fact, but how does logic work? If someone can simply persuade me about their point of view, is what they say fact? Or am I just easily persuaded?

Where do beliefs, values, and opinions fit in to all of this conversation about reason and facts?

If I consciously make sense of things, is my sense correct? Is my sense the same sense for others?

Reason is a process and the process of Reason can reduce the possibility of an endless question loop. Applying Reason is one way that humans can begin to make sense of a piece of information, or a concept, or a decision they need to make.

The Age of Reason

There are a variety of ways to consider the history of reason. Think about the history of world religions for example. In recorded human history (oral, visual, and written history) many polytheistic (multiple Gods and Goddesses) and monotheistic (one God or Goddess) religions have been present. Religions have served a variety of purposes for humans. Many ancient and modern religions provided explanations for the creation of the world, animals, and humans. There are many interesting and varied “creation stories” that survive to influence modern spirituality. Many religions provided structure and guidance about cultural norms, ethics, and behaviour. Religious versions of “right” and “wrong” have been used to reward, judge, and to punish for thousands of years. In the Greek and Roman world many Gods and Goddesses were used to explain and model strength, wisdom, power, and virtue. Returning to the History of Thinking, western culture has promoted Aristotle, Socrates, and Plato as the heroes of modern philosophical (and secular) thought and reason. In this Unit we’ll move to the Age of Reason and beyond to explore just a small bit of what it means in our modern time “to reason.”

The following chapter from “European History” provides some details on the Age of Reason or the Age of Enlightenment in western cultures:

The following chapter is taken from “European History” a collection of Wikipedia articles and details with the following attribution:

The copyright holder of this file allows anyone to use it for any purpose, provided that the copyright holder is properly attributed. Redistribution, derivative work, commercial use, and all other use is permitted. Here is a link to the source document for this chapter titled as follows:

Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment

7.1 Introduction

The Age of Science of the 1600s and the Enlightenment of the 1700s, also dubbed the Age of Enlightenment, introduced countless new concepts to European society. These ideas continue to permeate modern society. Many modern institutions have much of their foundations in the ideals of these times.

7.2 An Era of Enlightened Rulers

A new form of government began to replace absolutism across the continent. Whilst monarchs were reluctant to give up their powers, many also recognized that their states could potentially benefit from the spread of Enlightenment ideas. The most prominent of these rulers were Frederick II the Great Hohenzollern of Prussia, Joseph II Hapsburg of Austria, and Catherine II the Great Romanov of Russia.

In order to understand the actions of the European monarchs of this period, it is important to understand their key beliefs. Enlightened despots rejected the concept of absolutism and the divine right to rule. They justified their position based on their usefulness to the state. These rulers based their decisions upon their reason, and they stressed religious toleration and the importance of education. They enacted codified, uniform laws, repressed local authority, nobles, and the church, and often acted impulsively and instilled change at an incredibly fast rate.

7.2.1 Catherine the Great 1762-1796

Catherine the Great came to power because Peter III failed to bear a male heir to the throne and was killed.

Her enlightened reforms include:

- Restrictions on torture

- Religious toleration

- Education for girls

- 1767 Legislative Commission, which reported to her on the state of the Russian people

- Trained and educated her grandson Alexander I so that he could progress in society because of his merit rather than his blood line.

She was friends with Diderot, Rousseau, Voltaire. However, Catherine also took a number of decidedly unenlightened actions. In 1773 she violently suppressed Pugachev’s Rebellion, a massive peasant rebellion against the degradation of the serfs. She conceded more power to the nobles and eliminated state service. Also, serfdom became equivalent to slavery under her.

Foreign Policy

Catherine combated the Ottoman Empire. In 1774, Russia gained a warm water port on the Black Sea.

7.2.2 Frederick II the Great 1740-1786

Frederick II Hohenzollern of Prussia declared himself ”The First Servant of the State,” believing that it was his duty to serve the state and do well for his nation. He extended education to all classes, and established a professional bureaucracy and civil servants. He created a uniform judicial system and abolished torture. During his tenure, Prussia innovated agriculture by using potatoes and turnips to replenish the soil. Also, Frederick established religious freedom in Prussia.

7.2.3 Joseph II Habsburg 1765-1790

Joseph II Habsburg (also spelled as Hapsburg) of Austria could be considered perhaps the greatest enlightened ruler, and he was purely enlightened, working solely for the good of his country. He was anti-feudalism, anti-church, and anti-nobility. He famously stated, ”The state should provide the greatest good for the greatest number.” He created equal punishment and taxation regardless of class, complete freedom of the press, toleration of all religions, and civil rights for Jews. Under Joseph II a uniform law code was established, and in 1781 he abolished serfdom and in 1789 ordered the General School Ordinance, which required compulsory education for Austrian children. However, Joseph failed because he angered people by making changes far too swiftly, and even the serfs weren’t satisfied with their abrupt freedom.

7.2.4 England

As a result of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, England already had a Parliament and thus the concept of enlightened ruler did not take hold in England.

7.2.5 France

After Louis XIV the ”Sun King,” Louis XV took control from 1715 until 1774. Like his predecessor, he was an absolute monarch who enacted mercantilism. As a result of the influence and control of absolutism in France, France also did not encounter an enlightened ruler. In order to consummate an alliance between his nation and Austria, Maria Theresa of Austria married her daughter, Marie Antoinette, to Louis XV’s heir, Louis XVI. Louis . XV recognized that the fragile institutions of absolutism were crumbling in France, and he famously stated, ”Après moi, le déluge” , or ”After me, the flood.”

7.3 A War-Torn Europe

7.3.1 War of Austrian Succession

The war of Austrian Succession of 1740 to 1748 pitted Austria, England, and the Dutch against Prussia, France, and Spain. Upon Maria Theresa’s acquisition of the Austrian throne, Frederick the Great of Prussia attacked Silesia, and war broke out. In 1748 peace came at the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle. The treaty preserved the balance of power and the status quo ante bellum . Austria survived but lost Silesia, which began ”German Dualism” or the fight between Prussia and Austria over who would dominate and eventually unite Germany.

7.3.2 The Seven Years War

The peace in 1748 was recognized as temporary by all, and in 1756 Austria and France allied in what was known as the Diplomatic Revolution. The reversal of the traditional France versus Austria situation occurred as a result of both nation’s fear of a rising, militant Prussia.To consummate the marriage, Louis XVI married Marie Antionette. The Seven Years War engaged Austria, France, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and Saxony against Prussia and England. The purpose of the war was to annihilate Prussia, and took place at a number of fronts: in Europe, in America (where American citizens know it as the French and Indian War) and in India. At the Peace of Paris in 1763, the war concluded, and Prussia retained all of its territory, including Silesia. France ceded Canada to Britain and the North American interior to Spain, and removed its armies from India. It did, however, get to keep its West Indies colonies.

At this point, Great Britain became the supreme naval power and it began its domination of India.

7.3.3 The Partitioning of Poland

Poland was first partitioned on February 19, 1772, between Russia, Austria, and Prussia,in an agreement between them to gain more land and power in Europe. Poland was able to be partitioned because it was weak and had no ability to stop the larger and more powerful nations. The balance of power was not taken into consideration by France or England because the partitioning did not upset the great powers of Europe. The second partition involved Russia and Prussia taking additional land from Poland. After the second partition, which occurred on January 21, 1792, the majority of their remaining land was lost to Prussia and Russia. The third partition of Poland took place in October of 1795, giving Russia, Prussia, and Austria the remainder of the Polish land. Russia ended up with 120,000 square kilometres, Austria 47,000 square kilometres, and Prussia 55,000 square kilometres. This took Poland off of the map.

7.4 Science and Technology

The Enlightenment was notable for its scientific revolution, which changed the manner in which the people of Europe approached both science and technology. This was the direct result of philosophic enquiry into the ways in which science should be approached. The most important figures in this change of thinking were Descartes and Bacon.

The philosopher René Descartes presented the notion of deductive reasoning – that is, to start with a premise and to then discard evidence that doesn’t support the premise. However, Sir Francis Bacon introduced a new method of thought. He suggested that instead of using deductive reasoning, people should use inductive reasoning – in other words, they should gather evidence and then reach a conclusion based on the evidence. This line of thought also became known as the Scientific Method.

7.4.1 Changes in Astronomy

The Scientific Revolution began with discoveries in astronomy, most importantly dealing with the concept of a solar system. These discoveries generated controversy, and some were forced by church authorities to recant their theories.

Figure 23 Aristotle

Pre-Revolution: Aristotle and Ptolemy

The geocentric (earth-centred) view of the universe had been taught since the days of Aristotle. Ptomely’s ”Almagest” (c.2nd century CE) was the standard text used to teach students astronomy and remained so for hundreds of years. Ptolemy’s theories are a mixture of science and religion and to modern readers may come across as unusual though it must always be borne in mind that Ptolemy was building upon the works of earlier astronomers. Surprisingly a Greek philosopher called Aristarchus (310 BC – ca.230 BC) suggested that the earth moved around the sun and though this was common knowledge amongst all who studied astronomy it would be over a thousand years before he was proved right.

The early christian church (c.4th century CE) adopted the Ptolemaic system since it was in accord with biblical teaching. A universe without the earth at its center would negate divine purpose and Ptolemy’s idea of the spheres in harmony strengthened the creationist argument. The Enlightenment, which is also referred to as the Age of Reason, was a period when European philosophers emphasized the use of reason as the best method for learning the truth.

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543)

Figure 24 Heliocentric solar system

During the Renaissance, study of astronomy at universities began. Regiomontanus and Nicolas of Cusa developed new advances in mathematics and methods of calculation. Copernicus, although a devout Christian, doubted whether the views held by Aristotle and Ptolemy were completely correct. Using mathematics and visual observations with only the naked eye, he developed the Heliocentric, or Copernican, Theory of the Universe, stating that the Earth revolves around the sun.

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601)

Tycho Brahe created a mass of scientific data on astronomy during his lifetime; although he made no major contributions to science, he laid the groundwork for Kepler’s discoveries.

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630)

Kepler was a student of Brahe. He used Brahe’s body of data to write Kepler’s Three Laws of Planetary Motion, most significantly noting that planets’ orbits are elliptical instead of circular.

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

Galileo is generally given credit for invention of the telescope; although the device itself is not of Galileo’s design, he was the first to use it for astronomy. With this tool, he proved the Copernican Theory of the Universe.

Galileo spread news of his work through letters to friends and colleagues. Although the Church forced him to recant his ideas and spend the rest of his life under house arrest, his works had already been published and could not be disregarded.

Figure 25 Sir Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton (1642-1727)

Newton is often considered the greatest scientific mind in history. His Principia Mathematica (1687) includes Newton’s Law of Gravity, an incredibly ground-breaking study. Newton’s work destroyed the old notion of an Earth-centred universe. Newton also had a great influence outside of science. For example, he was to become the hero of Thomas Jefferson.

7.4.2 Developments in Medicine

Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564)

Vesalius studied human cadavers, a practice forbidden by church doctrine. His writing The Structure of the Human Body in 1543 renewed and modernized the study of the human body.

William Harvey (1578-1657)

William Harvey wrote On the Movement of the Heart and Blood in 1628, on the circulatory system. He was a doctor and an anatomist.

7.5 Society and Culture

As a result of new learning from the Scientific Revolution, the world was less of a mystical place, as natural phenomena became increasingly explainable by science. According to Enlightened philosophers:

- The universe is a fully tangible place governed by natural rather than supernatural forces.

- Rigorous application of the scientific method can answer fundamental questions in all

- areas of inquiry.

- The human race can be educated to achieve nearly infinite improvement.

- Perhaps most importantly, though, Enlightened philosophers stressed that people are all equal because all of us possess reason.

7.5.1 Precursors

There were a number of precursors to the Enlightenment. One of the most important was the Age of Science of the 1600s, which presented inductive thinking, and using evidence to reach a conclusion. The ideas of Locke and Hobbes and the notion of the social contract challenged traditional thinking and also contributed to the Enlightenment. Scepticism, which questioned traditional authority and ideas, contributed as well. Finally, the idea of moral relativism arose – assailing people for judging people who are different from themselves.

7.5.2 The Legacy of the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment began in France, as a result of its well-developed town and city life, as well as its large middle class that wanted to learn the ideas. The Enlightenment promoted the use of one’s reason, rather than accepting tradition. It rejected the traditional attitudes of the Catholic Church. Many ”philosophers,” or people who thought about subjects in an enquiring, inductive manner, became prominent. Salons were hosted by upper-middle class women who wanted to discuss topics of the day, such as politics.

The Enlightenment stressed that we are products of experience and environment, and that we should have the utmost confidence in the unlimited capacity of the human mind. It stressed the unlimited progress of humans, and the ideas of atheism and deism became especially prominent. Adam Smith’s concept of free market capitalism sent European economics in a new direction. Enlightened despots such as Catherine the Great and Joseph II replaced absolute monarchs and used their states as agents of progress. Education and literacy expanded vastly, and people recognized the importance of intellectual freedoms of speech, thought, and press.

7.5.3 Conflict with the Church

Although the ideas of the Enlightenment clashed with Church dogma, it was mostly not a movement against the Church. Most Enlightened philosophers considered themselves to be followers of deism, believing that God created an utterly flawless universe and left it alone, some describing God as the ”divine clockmaker.”

7.5.4 Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)

- dies before the enlightenment

- English Revolution shapes his political outlook

- Leviathan (1651) – life is ”nasty, brutish, and short” – people are naturally bad and need a strong government to control them.

- may be considered to be the father of the enlightenment: because of all the opposition he inspired.

Figure 26 John Locke

7.5.5 John Locke (1632-1704)

- specifically refuted Hobbes

- humanity is only governed by laws of nature, man has right to life, liberty, and property

- there is a natural social contract that binds the people and their government together;

- the people have a responsibility to their government, and their government likewise has a responsibility to its people

- Two Treatises on Civil Government justified supremacy of Parliament

- Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) – Tabula rasa – human progress is in the hands of society

7.5.6 Philosophers

Voltaire (1694-1776)

- stressed religious tolerance

Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755)

- Spirit of the Laws – checks and balances on government, no one group having sole power

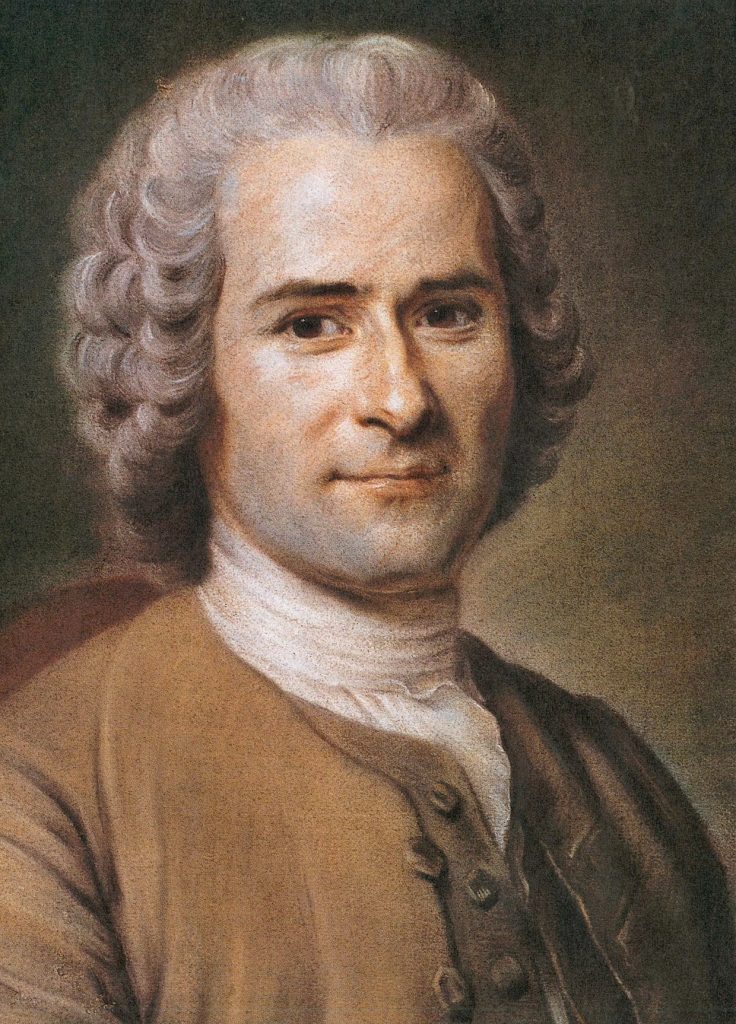

Figure 27 Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)

- social contract

- ”general will” – government acts for the majority

7.5.7 Rococo Art

Figure 28 Diana Leaving her Bath by François Boucher

The Rococo Art movement of the 1700s emphasized elaborate, decorative, frivolous, and aristocratic art. Often depicted were playful intrigue, love, and courtship. The use of wispy brush strokes and pastels was common in Rococo Art. Rococo Art is especially associated with the reign of Louis XV Bourbon in France. The French artist Boucher painted for Madame Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV. The most famous paintings of Boucher include Diana Leaving her Bath and Pastorale , a painting of a wealthy couple under a tree.