1.2: Reading Critically

As you take on a broader range of writing assignments in your college classes, it can be helpful to read as a writer, often called reading to write. “Reading to write” means approaching reading material with a variety of tools that help prepare you to write about that reading material. These tools can include things like previewing related assignments or lectures prior to reading, specific note-taking methods while reading, and ways of thinking about and organizing the information after completing the reading.

Critical reading is effective reading taken to the next step, but now we’re going to talk about how to use those reading skills to help us write about the texts we read. Instead of simply reading for your own purposes, you now will also read through the writer’s eyes, seeking to understand the deeper, interwoven meanings layered within a text. Critical reading involves the reader in grappling with the text—interacting with it.

The critical reader digs in and explores a text. They do some or all of the following:

- They analyze the structure of the piece. What kind of organization does it follow? Where is the thesis? What types of sentences and language are used? How are the paragraphs structured?

- They analyze the text itself, either exploring its content or its use of rhetoric, i.e., the ways the text uses language to make its message effective.

- They capture the text’s main points by summarizing its meaning.

- They critique the text, passing judgment on its effectiveness.

- They reach conclusions (make inferences) about the text.

- They combine their own ideas with the textual analysis to synthesize new ideas and insights.

You’ll begin, of course, by reading the text. Work your way through the suggestions in the “Reading Strategies” section, found in at the beginning of this chapter.

Reading critically involves look at all those different areas, and there are several different skills that we will look at below in this chapter and in the next to help you with this step.

Critiquing a Text

(Source: The Word on College Reading and Writing )

- When we summarize a text, we capture its main points.

- When we analyze a text, we consider how it has been put together—we dissect it, more or less, to see how it works

When we critique [1] a text, we evaluate it, asking it questions. Critique shares a root with the word “criticize.” Most of us tend to think of criticism as being negative or mean, but in the academic sense, doing a critique is not the least bit negative. Rather, it’s a constructive way to better explore and understand the material we’re working with. The word’s origin means “to evaluate,” and through our critique, we do a deep evaluation of a text.

When we critique a text, we interrogate it. Imagine the text, sitting on a stool under a bright, dangling light bulb while you ask, in a demanding voice, “What did you mean by having Professor Mustard wear a golden yellow fedora?”

Okay, seriously. When we critique, our own opinions and ideas become part of our textual analysis. We question the text, we argue with it, and we delve into it for deeper meanings.

Here are some ideas to consider when critiquing a text:

- How did you respond to the piece? Did you like it? Did it appeal to you? Could you identify with it?

- Do you agree with the main ideas in the text?

- Did you find any errors in reasoning? Any gaps in the discussion?

- Did the organization make sense?

- Was evidence used correctly, without manipulation? Has the writer used appropriate sources for support?

- Is the author objective? Biased? Reasonable? (Note that the author might just as easily be subjective, unbiased, and unreasonable! Every type of writing and tone can be used for a specific purpose. By identifying these techniques and considering why the author is using them, you begin to understand more about the text.)

- Has the author left anything out? If yes, was this accidental? Intentional?

- Are the text’s tone and language appropriate?

- Are all of the author’s statements clear? Is anything confusing?

- What worked well in the text? What was lacking or failed completely?

- What is the cultural context of the text? [2]

These are only a few ideas relating to critique, but they’ll get you started. When you critique, try working with these statements, offering explanations to support your ideas. Bring in content from the text (textual evidence) to support your ideas.

Drawing Conclusions and Synthesizing

Synthesizing

To synthesize is to combine ideas and create a completely new idea. That new idea becomes the conclusion you have drawn from your reading. This is the true beauty of reading: it causes us to weigh ideas, to compare, judge, think, and explore—and then to arrive at a moment that we hadn’t known before. We begin with a simple summary, work through analysis, evaluate using critique, and then move on to synthesis.

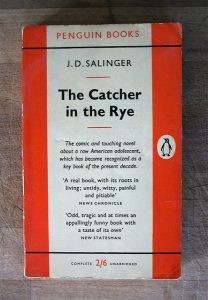

For example, many people read J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye at some point during their lives, often during high school. The book focuses on an angsty, rebellious teen who relates aspects of his teenage experiences, and he does this from his room in a mental institution. In the end, the teen understands more about himself and the world, and he begins to consider his possible future.

Many teens read this story and see themselves in it; grappling with the ideas in the text helps them better understand themselves and often encourages them to reach for their own futures. This is an example of how they draw their own conclusions from the text and synthesize their own directions and ideas.

Most of us can point to one or two books that have been life-changing—books that have held us captive for a moment in time and shaped our outlook. These are moments of synthesis. If this hasn’t happened to you yet, grab a good book (ask a teacher or librarian if you need suggestions), pour a cup of tea, and start reading.

Check Your Understanding: H5Ps

H5P activities from : Reading Comprehension Strategies – Academic Writing for Success, Canadian Edition 2.0

Self-Practice exercise 4.3

Self-Practice 2.12.1; 2.12.2; 2. 12.3

License

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Author

Brenna Clarke Gray (Author)

License Extras

This content was adapted by Brenna Clarke Gray into an H5P activity. It is based on content from Writing for Success – 1st Canadian Edition by Tara Horkoff and a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution.

Note add H5P activity from Reading Comprehension Strategies – Academic Writing for Success, Canadian Edition 2.0

Title

Self-Practice 2.15

License

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Author

Brenna Clarke Gray (Author)

License Extras

This content was adapted by Brenna Clarke Gray into an H5P activity. It is based on content from Writing for Success – 1st Canadian Edition by Tara Horkoff and a publisher who has requested that they and the original author not receive attribution.

Critical Thinking Exercises

Critiquing a Text

Let’s refer back to one of the texts we looked at previously and critique it.

In your own words, try to answer the questions below. To start with a critique, you don’t need to go in depth or use full sentences, but you want to jot down your ideas.

- How did you respond to the piece? Did you like it? Did it appeal to you? Could you identify with it?

- Do you agree with the main ideas in the text?

- Did you find any errors in reasoning? What might have been missed or not addressed?

- Did the organization make sense?

- Was evidence used correctly, without manipulation? Has the writer used appropriate sources for support?

- Is the author objective? Biased? Reasonable?

- Are the text’s tone and language appropriate?

- Are all of the author’s statements clear? Is anything confusing?

- What worked well in the text? What was lacking or failed completely?

- What is the cultural context* of the text?

The answers to these questions will help you start to build a critique of the text, which will in turn allow you to evaluate it, come to a conclusion or build a reflection of the text. We will continue on these skills in the following chapters.

Attribution

“1.2: Reading Critically” and the section on “Critiquing a Text” in “1.2: Reading Critically” is remixed and adapted from

Reading Critically in The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell; Jaime Wood; Monique Babin; Susan Pesznecker; and Nicole Rosevear, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

The section on “Drawing Conclusions and Synthesizing” in “1.2: Reading Critically” is adapted from Drawing Conclusions, Synthesizing, and Reflecting from The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell; Jaime Wood; Monique Babin; Susan Pesznecker; and Nicole Rosevear, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Pronounced crih-TEEK ↵

- *Cultural context is a fancy way of asking who is affected by the ideas and who stands to lose or gain if the ideas take place. When you think about this, think of all kinds of social and cultural variables, including age, gender, occupation, education, race, ethnicity, religion, economic status, and so forth. ↵

This is a definition.