Section 4 – Data Deposit, Sharing, and Archiving

Data Deposit: community care and control over data

Danica Evering; Amber Gallant; Mikala Narlock; and Lucia Costanzo

Research generates a lot of data about people in a each community. It preserves their thoughts or opinions, chronicles their movements, and documents pieces of personal information. Thinking about where data should be stored and whom it should be shared at the end of a project is important to protect both the data and the individuals and communities the data represents.

Where does data live once a project is complete?

Your answers may vary:

- On our organization’s server or shared drive

- In a community archive or library

- It’s on a hard drive (in our drawer, locked I think?)

- It’s owned by the city or federal government, so they store it

- On my desktop with my other files

- I did a quick search and oof I don’t actually know right now?

If this sounds like you and your team, you’re not alone! But we can think carefully about where data lives long-term. If data is stored on a server, it could be vulnerable to a cyberattack. Hard drives have a limited life expectancy[1]—and that’s if you don’t accidentally drop it or forget to eject it before you yank out the cord. We’re also seeing with government data that what might have been available publicly under one administration can be easily removed with a new administration.

Always store data long-term with enough information that you can still understand it if you open it 2 years later!

- Save your files in sustainable formats. Use a simple format that is not from a company. This lets you always make sure you can open it!

- Clean up your files before saving them permanently. We might make a good system but not follow it, so update filenames and folders.

- Don’t save everything. Have your parents given you the entire contents of your childhood bedroom…just in case you need it? We want to avoid this in our files. Make sure you review files and archive or delete the ones you don’t need anymore. Keep what is relevant to the research you’ve done, but you don’t need to keep the details with personal information in them, or random drafts you never returned to.

- Save it with a document that describes what it is. Save it with an overview file like a README containing what your different variables/column headers meant, what your file names mean, how you processed it, how you collected it.

- Whatever you do, do it on purpose!

There’s more information in our chapter File hacks – naming and organizing simplified.

What is Data Deposit?

Data deposit is not the only option for long-term safekeeping of data, and we’ll soon unpack why you might want to not deposit data. However, it’s important to make careful decisions around where data will go once a project is completed. As noted in the Data management in action tool, a research group may consider storing data on university servers and resources. If they do this, it could be difficult for community members to access data over time, especially if new community partners need access. Depositing data in a secure repository ensures everyone can access the data over time; and that everyone decides together who you share it with.

A data repository is a web platform and storage space to deposit data sets associated with research. This can be a place to store and archive data and make it easier for other people to find.

Data ownership is about having possession of the data collected or created over the course of a project. As data owners, you might also choose to assign responsibility for some care and maintenance activities to a data steward.

Data stewardship is the collection of day-to-day activities that ensure the long-term maintenance of the data. Data stewardship, and the activities people perform as data stewards, may be different from data ownership. For example, a community may own data that is stewarded by someone or something else (like an academic institution or academic researcher within an institution). That institution or researcher has the responsibility to ensure the data’s safety, security, and accessibility. Putting data in a research data repository means the repository is the data steward and takes care of your dataset so you don’t have to! However, trusting a data steward to care for your data DOES NOT mean you give up ownership. Many data repositories will let you lock down your files so people who want to use them have to request access from you.

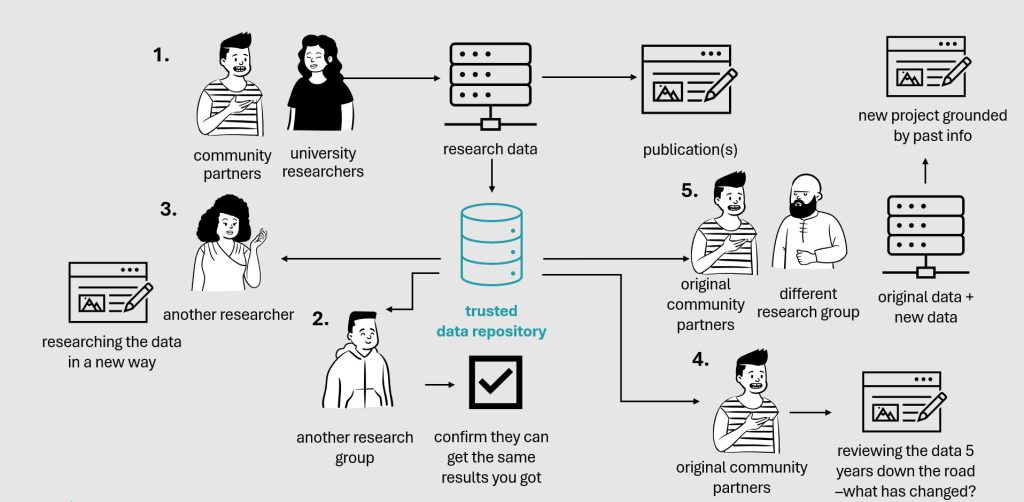

Data repositories help keep everything in one place for future research. Here’s how that can work:

- A research team of community partners and university researchers deposit data they’ve collected into a trusted data repository.

- Other researchers, journalists, policymakers, and others can request access to see what you collected, increasing trust in your research.

- Sometimes communities get asked the same question repeatedly by many different people. Having it in a data repository lets you grant access to researchers you choose so you don’t have to answer the same questions…all over again.

- You can also use this data for your organization over time and review it down the road to see what has changed.

- Finally, you can collaborate with a different research group and mix your new data with your old data to make a new project that’s grounded in past info.

Data in a repository is also searchable on the internet, which increases how many people know about your project. It also gets a DOI or “Digital Object Identifier.” You might have seen this in an article before. This is a permanent web address that always points back to a landing page about your data.

Data reuse, data sharing, and “secondary data”

Many community groups and their partners find research data helpful for long-term uses. A community organization, for example, may need data about who makes up the community it serves to inform its strategic planning. Data collected in a certain project might help it gain knowledge about the needs of the people in the community that it serves, create services that address these needs, and disseminate information about the needs of that community or other issues that that community faces. For many communities, the data collected might serve as a record or snapshot of cultural practices or norms or preserve stories or history in danger of being lost. Through data deposit and data sharing, community groups and organizations can better decisions about themselves.

We talked above about communities getting asked similar questions by many different researchers. Data reuse or data sharing can be a way for taxed communities to provide access to questions that have already been answered.

Let’s imagine a community of unhoused people living in tents within a city and an ad-hoc group of neighbours in solidarity with them. They may want to contribute to research to see some solutions to affordable housing. However, the police are forcibly moving them every week, throwing out everything they own, and they constantly have to find their support systems again (bathrooms, food, healthcare). The ad-hoc group is approached by social housing researchers who would like to understand the many reasons folks avoid shelter spaces (they can’t stay with their spouse, they’d be separated from their dog, they are afraid of getting sick). The researchers, unhoused folks, and ad-hoc group work together to do some interviews with 20 people and publish a paper. Then a year later, a team of public health researchers wants to understand the public health aspects of being unhoused–in tents and in shelter spaces…and their proposal includes remarkably similar questions.

Related to other ‘open’ initiatives, such as “open government” projects to increase transparency, open research is about sharing knowledge and building on each other’s work. Community organizations may have encountered this idea in the open government movement, which makes data from federal, provincial, and municipal governments public to support accountability and transparency. Researchers may have used data from Statistics Canada, or the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Similar to this, researchers are encouraged to share research data as part of grants and publishing. But one benefit of data sharing for community organizations and researchers is that the community can control access to data that has already been collected instead of responding to the same questions—nobody has time for that!

Why would you not want to deposit your data as a community?

Data collected from researched communities are often collected within a specific context of trust, sometimes established over months and sometimes years. Researchers who interview or conduct focus groups with refugees, LGBTQ communities, and folks with access needs, might say they could never share their data because of the framework of established trust between researcher and participants.

- Context can be hard to capture and share—relationships, politics, infrastructure, and more. This gets harder over time to understand. How much can you tell just from a transcript? Does the transcript include information about the tone of someone’s voice, saying something lighthearted or with tears in their voice?

- Data can be too sensitive, and it can be hard de-identify a transcript. You might take out so much information that the data becomes unusable. A female, Southwest Asian and North African (SWANA), librarian might be ambiguous enough. But if she mentions what particular branch she works at, her colleagues and patrons may be able to identify her. We might also be working with a group that knows each other very well, such as parents of children in a daycare.

- There is also a persistent and relevant concern that data might be used in bad faith–we might think about research data that could be used to further damage-centered narratives (thinking about Eve Tuck’s excellent open letter to Indigenous communities, Suspending Damage). Racialized and marginalized communities experience inordinate harm from visibility. [2]

With all these things in mind, not depositing data can be an act of care, a way of refusing to be surveilled.

But why might you want to deposit your data as a community?

Sharing community data can save time and resources, avoid over-research, and allow communities to work with multiple researchers. Let’s go a bit deeper:

- Save time and resources: If you’ve ever been a research participant, you know how much time and resources can be involved in community research work. If research involves analysis, transcription, or coding, all of that takes a lot of time. In the case of focus groups or interviews, it would be impossible to capture it again, even if you had the energy to try.

- Avoid over-research: Victoria Smith, the Policy, Privacy, and Sensitive Data Coordinator with the Digital Research Alliance of Canada, has discussed the nature of community research participants as over-researched.[3] Consider a survey and focus groups considering the workplace experiences of medical laboratory technologists. This group is already working overtime to keep up with demand. Even though they are motivated to participate, it may be hard for an individual to contribute to more than one study. We could imagine 20 different researchers who might approach the same community for the same information again and again, contributing to research fatigue. Instead, if one researcher shares previously gathered data, other researchers can work with that dataset instead of re-engaging community members, reducing the burden of time and administration on communities while ensuring folks benefit from research.

- Work with multiple researchers: Research participants participate because they want to contribute to an issue the research will address. However, research takes time and energy and comes with some risk to participants. Data sharing can help research participants have access to data if they work with researchers in the future.

- Allows for more engagement: The Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton notes that access to data facilitates important debate about the nature of our communities and the development of innovative solutions. It also helps engage the citizen and public in these important debates within their communities.

Preserving data histories

A final consideration we would like to bring into this conversation is the maintenance of data as an act of community care (this concept comes from the Maintainers!).[4] The data we collect capture a snapshot of who we are at specific moments in time. They reflect our relationships, values, desires, and needs. These snapshots include oral histories, photos, videos, narratives, and even numerical data, all of which serve as vital pieces of information in shaping how our community’s stories are told and represented in official archives.

Unfortunately, many communities are underrepresented, or mis-represented, in these archives, resulting in only a partial telling of their stories. Consider, for example, Eric Luse’s famous photograph of the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus, taken in 1993 for the San Francisco Chronicle.[5][6] The image features 122 chorus members, with 115 men dressed in black and facing away from the camera, and 7 dressed in white, facing forward. The men in black symbolize those lost to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and the few men in white represent its few survivors among the original members of the chorus. This powerful visual evokes the profound impact of the epidemic on the community while prompting questions about the untold stories of those 115 men.

Stories and narratives about our communities as individuals and as a collective are built on data like this photograph. By preserving and maintaining community data, we can combat under- and misrepresentation, allowing us to portray our communities more fully. The act of preservation becomes a revolutionary statement of the community’s ownership over and continued ability to tell its stories.

Sharon Webb is a queer researcher in England working in queer archiving and oral history. She worked with a community organization called Queer in Brighton to archive the queer community’s oral histories. It is not safe for everyone to be able to access these histories, based on the violence queer communities experience. So, access to the archive is not open to the public. It is open to the community, an interesting possibility to consider with data sharing and archiving as well.[7]

The maintenance of community data is essential for informing the future of that community. Community needs and demographics naturally change over time. Knowing who belonged to the community at a point in time, who belongs to it now, and what their historical and current needs were can inform care initiatives and efforts, and drive policies and programs that will support the community well into the future.

These stories are incredibly important. They help us understand who we are; and whose protests and resistance we live in the footsteps of (this framing is how activist and artist Tings Chak has acknowledged land). It’s important for queer folks to know the histories of our elders. Caring for data is an essential act of maintenance, of ensuring the through-line is clear.

- Andy Klein, "Hard Drive Life Expectancy," Backblaze, July 20, 2022, https://www.backblaze.com/blog/hard-drive-life-expectancy/ ↵

- Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15 ↵

- Goodman, A., Morgan, R., Kuehlke, R., Kastor, S., Fleming, K., Boyd, J., & Society, W. A. H. R. (2018). “We’ve Been Researched to Death”: Exploring the Research Experiences of Urban Indigenous Peoples in Vancouver, Canada. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 9(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2018.9.2.3 ↵

- Maintainers, T. I., Olson, D., Meyerson, J., Parsons, M. A., Castro, J., Lassere, M., Wright, D. J., Arnold, H., Galvan, A. S., Hswe, P., Nowviskie, B., Russell, A., Vinsel, L., & Acker, A. (2019). Information Maintenance as a Practice of Care. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3251131 ↵

- May, M. (2006, June 4). Gay Men's Chorus carries on / A quarter-century after the start of the epidemic, the group has suffered the deaths of 257 members. SFGate. https://www.sfgate.com/health/article/Gay-Men-s-Chorus-carries-on-A-quarter-century-2533823.php ↵

- Gonzalez, S. (2018, December 1). World AIDS Day: Resurfaced photo from 1993 reminds people of infection's impact on LGBTQ community. 10 News San Diego. https://www.10news.com/news/national/world-aids-day-san-francisco-gay-mens-chorus-photo ↵

- Sharon Webb, Queer in Brighton, https://queerheritagesouth.co.uk/s/queer-heritage-south/page/contact ↵

"A DOI (digital object identifier) is a unique number used to permanently identify online articles, documents, and other objects -- including journal articles in electronic databases, datasets, audio/video content, ebooks, and research reports." https://www.lib.sfu.ca/find/journals-articles/what-doi