Section 1 – Introduction

Getting started: managing community research data

Shahad Al-Saqqar; Danica Evering; Subhanya Sivajothy; and Isaac Pratt

Tiny to large – from neighbourhood organizations to large non-profits

Research data management—also known as RDM—is not one-size-fits-all.

Data Management Plans will vary depending on the community involved, the sensitivity of the data, the resources available, and the objectives of the organization and the research. For example, smaller neighbourhood groups or grassroots organizations might prefer to focus on simple data storage and security methods with basic data privacy and ethics guidelines. On the other hand, larger non-profits might have more capacity and resources to acquire dedicated staff and funding for a robust security system with structured databases and formal privacy policies. Throughout this document, we aim to highlight RDM suggestions and solutions that will help you decide what works for you/your organization/your situation, rather than share a “gold standard” that might be unattainable.

Community participants and researchers are so busy. Take these tools and make them work for you! Our templates and guidelines can be used in each phase of this research process: deciding if you want to work together, planning what you’ll do, collecting data, sharing knowledge with others. Use, copy, and adapt these tools so you don’t have to stare at a blank page. All of our documents have a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 4.0 International (CC BY SA 4.0) License. You just need to cite us, link to this license, say if any changes were made, and share it under the same terms under which you used it.

To support reading, we’ve put essential text in bold and highlighted so you can scan it at a glance.

Data risk level is also important to the management of data. To support this legibility, we’ve tagged items as low, medium, or high risk.

To support scaling, we have provided suggestions through the document for a range of community research:

Small Org: Are you a neighbourhood network, an ad-hoc group organizing against hate in your city, a tiny nonprofit? With only 1–5 staff, small organizations may want to participate in research, but don’t have the resources to support store large datasets long-term. While this is true, you might have board committees or volunteers who are interested in taking an active role in data management.

Small Org: Are you a neighbourhood network, an ad-hoc group organizing against hate in your city, a tiny nonprofit? With only 1–5 staff, small organizations may want to participate in research, but don’t have the resources to support store large datasets long-term. While this is true, you might have board committees or volunteers who are interested in taking an active role in data management.

Large Org: On the other end of the spectrum, larger organizations–service organizations like the YWCA or government systems like school boards–may have established IT teams and already pay for server space. They often also have dedicated research and advocacy staff who already have a role in data management. You might consider activities like storing research data internally, developing formal bylaws for data access, and adding research data management to the duties of a point person on staff.

Large Org: On the other end of the spectrum, larger organizations–service organizations like the YWCA or government systems like school boards–may have established IT teams and already pay for server space. They often also have dedicated research and advocacy staff who already have a role in data management. You might consider activities like storing research data internally, developing formal bylaws for data access, and adding research data management to the duties of a point person on staff.

No Org: Sometimes researchers conduct community-based research with a group that doesn’t have a single affiliated organization, for example, a group of refugees from one country or a queer community that might be made up of several different small groups. In these cases, conversations around management and access to community data are still critical. However, researchers might need to rely on established IT and data storage systems at their university, or work with a third-party stakeholder group such as a public library.

No Org: Sometimes researchers conduct community-based research with a group that doesn’t have a single affiliated organization, for example, a group of refugees from one country or a queer community that might be made up of several different small groups. In these cases, conversations around management and access to community data are still critical. However, researchers might need to rely on established IT and data storage systems at their university, or work with a third-party stakeholder group such as a public library.

“Community” “research” “data”

What do we mean when we say “community” or “research” or “data”? We are all new to each other and so to have some shared language, we have included a glossary. Just hover over the terms to learn more or access them all at the end of this Pressbook. However, we need to get on the same page about the three main concepts of this toolkit.

“Community”

A community is a group of people brought together: by a shared place, an activity they all do together, their identity, or for other reasons. MacQueen et al. write about 5 core elements:[1]

- Locus: A place – neighbourhood, city, setting (bar, workplace, barbershop, library)

- Sharing: Common interests and shared perspectives

- Joint action: Shared activities – socializing, volunteering, organizing

- Social ties: Relationships between people

- Diversity: Difference within a community and groups that are structurally excluded from communities (race, sexuality, age, drug use, accessibility)

Communities may have some or all these elements. An online community of people with the same rare disease might not share a physical space but are defined by shared perspectives or organizing together. Students within a school board might have all these aspects, but fewer common interests and a big diversity of experiences. Communities are often remarkably diverse, and it is important to consider this in the way research data is managed – one size rarely fits all.

“Research”

Research is a process of finding out something that is true.

It can mean studies done by teams at a university or other research organizations, community organizations, nonprofits, and more. This happens through surveys, with consultants, or looking at statistics and open government data. It can also be done in collaboration: social justice organizations, community councils, and non-profits might be approached by university researchers to connect to community participants. They are likely to see both positive impacts of research on policy decisions but also the trickier aspects such as over-research,[2] surveillance,[3] and research that tells stories only includes brokenness without hope and resilience alongside it.[4]

“Data”

Do we even have data to manage? Researchers working with biological samples or government statistics may feel confident they’re working with research data. But what if you’re not part of a research institution? What if your research is rooted in creative practice? What if your research is focus groups or interviews?

Data can be text, numbers, images, recordings, software, algorithms, workflows, and more. From this toolkit’s Conversational Data Management Plan: if you can use it as a building block to produce new knowledge or understanding, it could qualify as research data. Communities may have negative relationships with universities and research; they might also have different standards for data than academia. In these cases, they may choose to replace “data” with “stories,” “evidence,” or another word. As such, a comprehensive cultural understanding of data sees it as something that is “generated, protected and interpreted.”[5]

Data can be text, numbers, images, recordings, software, algorithms, workflows, and more. From this toolkit’s Conversational Data Management Plan: if you can use it as a building block to produce new knowledge or understanding, it could qualify as research data. Communities may have negative relationships with universities and research; they might also have different standards for data than academia. In these cases, they may choose to replace “data” with “stories,” “evidence,” or another word. As such, a comprehensive cultural understanding of data sees it as something that is “generated, protected and interpreted.”[5]

In community research, data is collected from a community: survey responses, focus group notes, stories, interviews, oral histories, photovoice projects, artwork, and more. It may also be data that is reused: open data from the county, statistics, survey data collected by another community organization, administrative data from outreach programs, archival photos, samples from films, historic maps; and beyond.

What is research data management?

This set of tools supports Research Data Management (RDM): caring for research data from before it is collected until after the project is over.

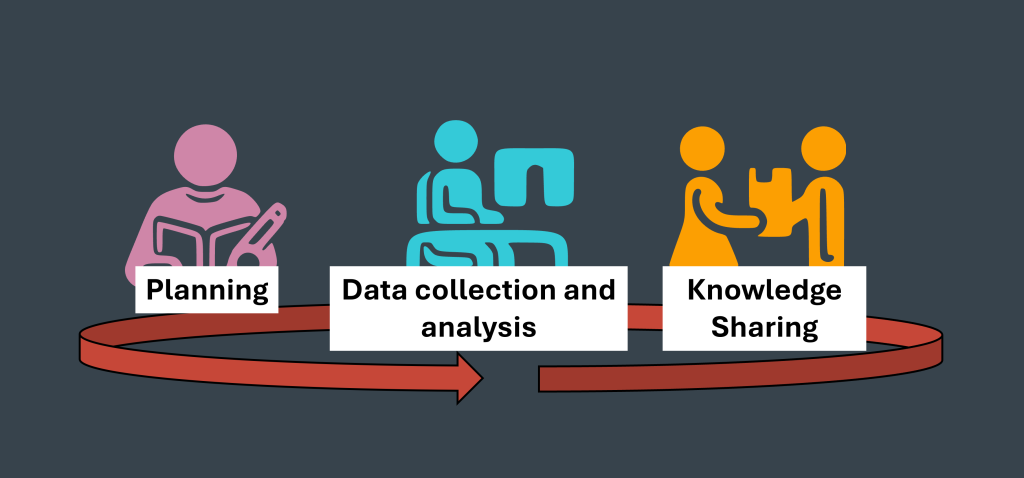

We can see this happening in three moments:

We can see this happening in three moments:

- Planning happens before you start research: building relationships between community partners and researchers, applying for grants, checking ethics approval, agreeing on how you will collaborate. Data management activities include determining roles and responsibilities, making a Data Management Plan, finding existing data you want to use (like Open Government statistics), deciding where to store everything.

- Data collection and analysis is what we think of as “doing the research”: sending out surveys, organizing focus groups and interviews, creating art, analyzing and visualizing internal administrative data and government statistics. Data management activities include removing personal information from datasets, organizing data, updating your Data Management Plan, taking notes, and conducting security updates.

- Knowledge Sharing should occur throughout the research process. While researchers might share data with the wider community at the end of a research project, a community can also be immersed in data management and the ongoing sharing of knowledge emerging from the research as it progresses. It is important to share, so people know what they have contributed and that what they’ve said matters and is being used. Data management activities include preparing data for archiving, or sharing data with communities and other researchers.

- MacQueen, K. M., McLellan, E., Metzger, D. S., Kegeles, S., Strauss, R. P., Scotti, R., Blanchard, L., & Trotter, R. T. (2001). What Is Community? An Evidence-Based Definition for Participatory Public Health. American Journal of Public Health, 91(12), 1929–1938. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1929 ↵

- Goodman, A., Morgan, R., Kuehlke, R., Kastor, S., Fleming, K., Boyd, J., & Society, W. A. H. R. (2018). “We’ve Been Researched to Death”: Exploring the Research Experiences of Urban Indigenous Peoples in Vancouver, Canada. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 9(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2018.9.2.3 ↵

- Browne, S. (2015). Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822375302 ↵

- Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15 ↵

- Gitelman, L. (Ed.). (2013). “Raw data” is an oxymoron. The MIT Press. ↵

Research is a process of finding out something that is true. It can mean studies done by teams at a university or other research organizations, but community organizations also conduct research. This happens through surveys, collaborating with consultants, or looking at statistics and open government data.

Refers to information collected. This can include facts, measurements, or observations. They can come in many forms such as text, numbers, symbols, images, videos, sound, drawings, diagrams, code, or files. (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2021)

A document, usually for a specific project or program, that describes how you will collect, keep safe, and share data. A Data Management Plan is a helpful guide for researchers to follow and make sure everyone involved is on the same page. They are “living documents” created to be updated over time as a project evolves. (Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, 2021)

Data sharing means making the data available for use by others after you’ve completed the project it was collected for. Those others might include community members, academic researchers, or other individuals or groups that might not be involved in the original project, but that might have an interest in reusing the data. Some of the groups that fund research or publishers of research are asking for data sharing as a way to make research processes clear, make sure another researcher can repeat an experiment, and making sure the data is used by the most possible people. This requires people working with data to make sure they say where they got the data so everyone gets credit. (Defined by authors, inspired by NIH, n.d.-c)