Acknowledging the land and Indigenous Data Sovereignty

Danica Evering

This project was started at McMaster which is close to two First Nations and part of several treaties.

McMaster University is based in Ohròn:wakon (in the ditch/ravine),[1] in the curve of the Niagara Escarpment, on the traditional territories of the Mississauga and Haudenosaunee nations. We are near to both the Six Nations of the Grand River and Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, as well as many urban Indigenous communities. We are all treaty people; this land is also covered by the Between the Lakes Treaty (1792) and is very close to the 1784 Haldimand Treaty which holds the land six miles to each side of the Grand River as a tract for Six Nations, which is currently not being honored—like many treaties across the country.

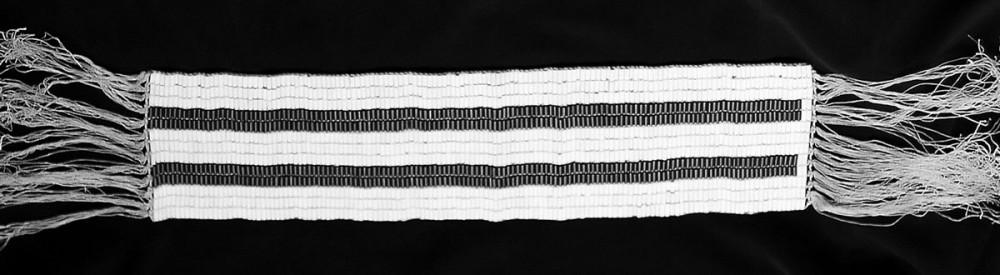

We are party to the Two Row Wampum which represents a canoe (First Nations) and the sailboat (settlers) not interfering with each other.

Last year, the McMaster Indigenous Studies department hosted a collective reading of O da gaho de:s: Reflecting on our journeys by Gae Ho Hwako or Elder Norma Jacobs, which talks about the Kaswen:ta, the Two Row Wampum.[2] This wampum belt has two purple parallel lines, representing a canoe (Haudenosaunee) and a ship (Dutch settlers). White beads represent the river of life between and beyond. Framed as brothers, as equals, the Dutch settlers and Haudenosaunee are both responsible for taking care of the river. However, the paths of the ship and the canoe do not cross. Settlers are responsible for staying in our lane and not interfering in the work of the canoe.

Indigenous data should be approached like that of a sovereign nation.

In addition to there being many great resources to support research by and with Indigenous communities, the nature of Indigenous data is very distinct. As this toolkit was developing, many colleagues mentioned Indigenous data and community data in the same breath. However, Jeff Doctor, Impact Strategist at Animikii Indigenous Technology, has spoken about Haudenosaunee chief Deskaheh’s insistence at the inception of the League of Nations that like Canadians, Haudenosaunee are also sovereign peoples and political actors.[3] Researchers often speak about Indigenous data in the same way as data from racialized or equity-seeking communities. There are of course overlaps: Indigenous peoples experience racism and inequity. Many different groups across the world share common experiences of genocide and colonization, perpetrated by Britain and its colonies, France, Germany, Netherlands, Portugal, the United States, Spain, and others. However, ongoing land theft and the government-to-government relationship between sovereign Indigenous nations and the Government of Canada as a constitutional monarchy add layers of complexity that impact research. That work is and should continue to be led by Indigenous organizations.

With this toolkit, we are working within the sailboat, not interfering with the canoe.

This toolkit is not intended for research by and with Indigenous communities. We don’t want to replicate work already being done, but support it, and action it, and build alongside it. With that said, our resources are available as Creative Commons if the language and frameworks we have developed are helpful to groups who want to take up and adapt for the more specific context of Indigenous Data Sovereignty.

Resources

There are already strong Indigenous organizations and researchers guiding work on data sovereignty:

-

- The First Nations Information Governance Centre supports First Nations in working with researchers.[4]

- The Manitoba Métis Federation endorses OCAS principles, which asserts ownership, control, access, and stewardship for research data.

- ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᑕᐱᕇᑦ ᑲᓇᑕᒥ (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami) has a National Inuit Strategy on Research which ensures Inuit access, ownership, and control over data and information.[5]

- Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) has developed the CARE principles, highlighting the need for research involving Indigenous communities to have collective benefit, while the communities themselves have the authority to control their data, with the goal of conducting responsible and ethical research.[6] Self-Governing Indigenous Governments have developed their own toolkit for Data Governance and Management.[7]

- The McMaster Indigenous Research Institute (MIRI) has a McMaster Indigenous Research Primer which guides those who are engaging with Indigenous Peoples and their work.

- Northeast Turtle Island in Mohawk. (2015, February 4). The Decolonial Atlas. https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/2015/02/04/northeast-turtle-island-in-mohawk/ ↵

- Gae Ho Hwako (with Leduc, T. B.). (2022). Ǫ da gaho de:s: Reflecting on our journeys. McGill-Queen’s University Press. ↵

- Jeff Doctor. (2021, December 3). Are Individualistic Data Policies and Designs Fuelling Digital Colonialism? MyData Canada. https://vimeo.com/653038251 ↵

- Welcome to The Fundamentals of [pb_glossary id="573"]OCAP®[/pb_glossary]. (n.d.). The First Nations Information Governance Centre. Retrieved January 9, 2025, from https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/take-the-course/ ↵

- ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᑕᐱᕇᑦ ᑲᓇᑕᒥ (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami). (2018, March 22). National Inuit Strategy on Research. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. https://www.itk.ca/national-strategy-on-research-launched/ ↵

- Carroll, S. R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M., Russell, K., & Stall, S. (2021). Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Scientific Data, 8(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00892-0 ↵

- Self-Governing Indigenous Governments (SGIG) Data Steering Committee. (2020). Data Governance & Management Toolkit. https://indigenousdatatoolkit.ca/ ↵

Research in any area that is done by or related to First Nations, Inuit, Métis, and other Indigenous nations and people. This research can also include topics on their cultures, experiences, or knowledge from past and present. (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, 2021)

Refers to any kind of information collected by, with, or about Indigenous people. This can come in forms such as text, numbers, symbols, images, videos, etc. The data can be about their land, water, people or culture. (NCRIS, 2022)