26 Understand Confirmation Bias

Robert Sternberg

Confirmation bias is defined as “the tendency to seek or favour new information which supports one’s existing theories or beliefs, while avoiding or rejecting that which disrupts them” (Oxford English Dictionary, 2019).

What You’ll Learn:

- What confirmation bias is

- What confirmation bias looks like in action (or lessons for how to avoid it)

Do you like puzzles?

“A Quick Puzzle to Test Your Problem Solving” by David Leonhardt (2015) is based on an experiment conducted by Peter Cathcart Wason, who is credited with coining the phrase “confirmation bias.”

Try solving the puzzle yourself here. Make sure to take note of the following instruction: “You can test as many sequences as you want” (Leonhardt, 2015), but you only get one guess.

What Is Confirmation Bias?

If you’re like most people, when you tried to solve “A Quick Puzzle to Test Your Problem Solving” you probably entered sequences of numbers that obeyed the rule rather than disobeyed it. And maybe that led you to guess that “[e]ach number is double the previous number” (Leonhardt, 2015). A good guess! But incorrect. And possibly premature.

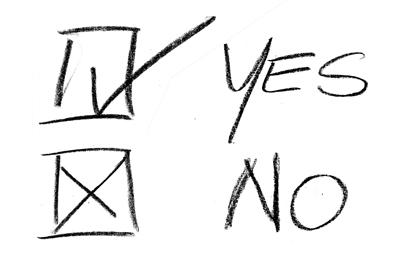

According to Leonhardt, entering a sequence of numbers that disobeyed the rule rather than obeyed it may have been the key to solving the puzzle. However, as the author states in their explanation, the majority of people “don’t want to hear the answer ‘no.’ In fact, it may not occur to them to ask a question that may yield a no […] It’s a lot more pleasant to hear ‘yes.’ That, in a nutshell, is why so many people struggle with this problem” (para. 3).

In other words, it’s a natural human tendency to seek information that confirms our beliefs (yes’s) rather than contradicts them (no’s). Or, as Leonhardt explains, “[n]ot only are people more likely to believe information that fits their pre-existing beliefs, but they’re also more likely to go looking for such information” (para. 6).

Confirmation Bias in Action (or Lessons for How to Avoid It)

Author David Leonhardt offers the following two examples of confirmation bias within the context of reading and writing:

If you’re politically liberal, maybe you’re thinking of the way that many conservatives ignore strong evidence of global warming and its consequences and instead glom onto weaker contrary evidence. Liberals are less likely to recall the many incorrect predictions over the decades, often strident and often from the left, that population growth would create widespread food shortages. It hasn’t. (para. 7)

Reading this, are you surprised that there is such a growing divide between liberal and conservative viewpoints today? Maybe one explanation for this is that each side is virtually ignoring the other.

Let’s take a detailed look at two other examples of possible confirmation bias in action. By doing so, hopefully we can learn some lessons for how to avoid it.

Example 1: Cellphones in School

If you already believe that cellphones should be kicked out of school, then this editorial, and many others just like it, will serve as confirmation of your belief. And if you only give your attention to articles like this one, you may be less open to hear the other side.

Now, let’s imagine you’ve come to this editorial as someone who does not believe that cellphones should be kicked out of schools.

Let’s take an issue we can all relate to: cellphones in the classroom. On October 25, 2017, an editorial was published in Bloomberg News called “Kick Mobile Phones Out of School”; in it, research was used to show that cellphones “[contribute] to sloppy work, reduced concentration and lower problem-solving capacity” (para. 2), among other adverse effects.

Read the source.

Looking Up is an award-winning blog by Andrew Campbell, an Ontario-based primary school teacher. In his blog post “We Need Cellphones in School Because They’re Distracting” (2017), Campbell, who opposes banning cellphones in the classroom, discussed the Bloomberg News editorial mentioned above.

Campbell doesn’t dispute the editorial’s claim that cellphones can be a distraction in school. In fact, he accepts it. What he disputes is the solution to this problem. “The ability to self-regulate the use of devices,” he claims, “is a critical skill if students are to become productive adults” (para. 10). He goes on to write the following:

This, not their role in learning, is the most important reason we need cell phones in [the] classroom. Students need to learn, from an early age, how to regulate their use of digital devices. Soon cell phones won’t be considered technology. They’ll be tools we use for certain jobs and then put away. But until then schools and teachers can play a vital role in teaching students how to use cell phones effectively and responsibly. (para. 11)

Example 2: Climate Change

Maxime Bernier, the leader of the People’s Party of Canada, wrote a controversial tweet during the lead up to the 2019 Canadian federal election in which he disputed Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s use of the word “pollution” to describe carbon dioxide, or CO2 (Trudeau had used the word while proposing his plans for a carbon tax).

“CO2 is NOT pollution,” Bernier (2019) tweeted. “It’s what comes out of your mouth when you breathe and what nourishes plants.”

You can read more about his controversial tweet here.

Bernier (2019) repeated his claim that “CO2 is NOT ‘pollution’” in a tweet appearing a few months later, which received 7.4 thousand likes. Here’s a brief sample of its favourable replies:

- “Thank you Max for speaking the truth” (Nelmes, 2019).

- “Bravo [. . .] I said it all along, CO2 is food for plant” (Phoenix, 2019).

- “Maxime Bernier, thank you, thank you, thank you for speaking TRUTH” (Shayne, 2019).

Whereas a carbon tax can and should be debated among citizens and politicians, the same can’t be said for the way that CO2 pollutes our planet. In fact, in 2007, the US Supreme Court ruled that CO2 is a pollutant. And it’s not alone in its judgment. Climate scientists and world leaders from around the globe agree.

Here, we may see confirmation bias in action, and a lesson for how to avoid it. Despite the unscientific nature of Bernier’s tweets, there were many who not only liked them but replied to them favourably. Why is that?

- Is it because their opposition to a carbon tax was so strong that they were inclined to agree with him, despite the absence of science in his tweets?

- By agreeing with him, is it also possible that they were avoiding or rejecting contradictory information, like the US Supreme Court’s 2007 ruling that CO2 is a pollutant?

If you answered “yes” to both questions, then you will probably agree that confirmation bias played a role in their decision to like and favourably reply to Bernier’s tweets.

Tip

Did you know that confirmation bias is just one form of bias? Familiarize yourself with these other forms of bias by looking up their definitions:

- Implicit bias

- Explicit bias

Try It!

As we learned from the puzzle activity at the beginning of this unit, “[w]hen you seek to disprove your idea, you sometimes end up proving it—and other times you save yourself from making a big mistake. But you need to start by being willing to hear no” (Leonhardt, 2015, para. 14).

With that in mind, sort the following two claims into their appropriate columns:

Now, go search for information online that contradicts your opinion. For example, if you “agree” that cellphones are harmful for students, seek information that claims the opposite. Similarly, if you “disagree” that climate change is primarily caused by humans, seek information that claims the opposite. Share your findings with your class.

Tip

One proven method to combat confirmation bias is to seek and be open to information that disproves or contradicts—rather than supports—your opinion.

Before continuing, evaluate your learning so far and think if you…

See related subtopics in Foundations, Build Your Toolkit, and Absorb.

Andrew Campbell’s blog post is an excellent example of what we can do to avoid confirmation bias. Consider the following habits he demonstrates in his blog post: