13 Develop Flow

Philip Loosemore

Connect your ideas so readers can follow.

What You’ll Learn:

- How to group and sequence ideas

- How to connect ideas

Flow in writing is the sense of connection between ideas.

Writers should:

- Group similar ideas together

- Order (sequence) ideas logically

- Connect each sentence to the next

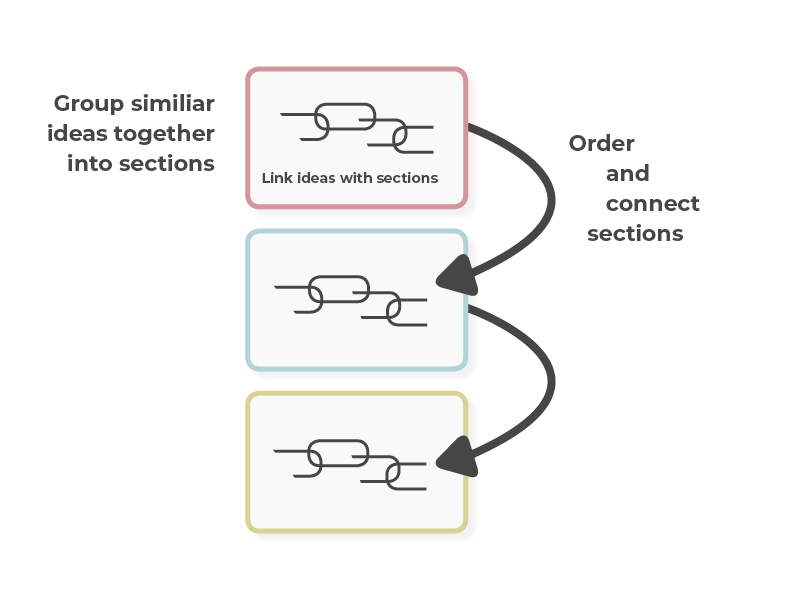

Group, Sequence, and Connect

A first draft is exploratory. Even if you’ve planned and outlined your project, ideas might pour out at random. It’s not easy to write a first draft. Give yourself permission to write prose that doesn’t yet flow:

1 Students are greatly in debt. 2 In a survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. 3 Postsecondary institutions are trying to enhance student life. 4 Credentials are no longer enough for employment.

Statements 1, 2, and 4 relate to the pressures and problems postsecondary students face. But nothing focuses these statements or pulls them together. Meanwhile, point 3 probably doesn’t belong.

Strategy 1: Group and Sequence Ideas

To solve this problem, separate out ideas into larger topics, put them in logical order, and directly identify the topics for your reader:

1 Students face many pressures today. They are greatly in debt. In a survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. Credentials are no longer enough for employment.

2 There have been attempts to address the issue. Postsecondary institutions are trying to enhance student life.

Here we’ve

- created two separate topics;

- put them in a logical order (problem → solution); and

- identified each with a topic sentence (1, 2).

By default, topic sentences should go at or near the start of a given paragraph. It’s also possible to put a topic sentence at the end:

Students are greatly in debt. In a survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. Credentials are no longer enough for employment. Students face many pressures today.

Strategy 2: Connect Ideas

Grouping and sequencing help, but the ideas still feel disjointed. We need to link them more with connectives. Connectives are those little words that link, or connect, ideas together:

- Also

- Moreover

- For example, for instance

- Yet

- But

- However

- More importantly/most importantly

- In short

These connectives help you add ideas, contrast two or more ideas by showing difference, summarize, and so on. By using them, you show your readers these same logical connections. Your writing feels more cohesive as a result.

Sometimes punctuation can help in the same way. For example:

- A colon (:) often shows that an example follows.

- An em-dash (—) can be used to emphasize or add an idea—just as this one does.

Students face many pressures today. For example, they are greatly in debt. They’re also stretched thin: In a survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. Worse, the credentials they’re earning are no longer enough for employment.

There have been attempts to address the issue. For instance, postsecondary institutions are trying to enhance student life.

The words and phrases “for example,” “also,” and “worse,” and the colon (“stretched thin:”) all link ideas together and show the relationships between them. Let’s look at what each connective is doing:

- “For example” connects the subsequent idea to the previous one as an instance or illustration.

- “Also” adds a new, equal idea onto the previous one. (In fact, the entire clause “They’re also stretched thin” is one big connective, showing the relationship between student debt and student overwhelm.)

- The colon (:) after the word “thin” shows that an example or piece of evidence is coming.

- The word “worse” comparatively weights the following idea as more important than the previous one(s), in a negative sense (i.e., one example worse than the other two).

Note you can still put the topic sentence of the first paragraph at the end:

Students are greatly in debt. They’re also stretched thin: In a survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. Worse, the credentials they’re earning are no longer enough for employment. In short, students face many pressures today.

Here the connectives work the same way as before, and the new one, “in short,” brings all the ideas to a point, and alerts the reader that the next idea is a summary and explanation of all the previous ones.

Tip

Not every sentence you write will have a connective word or phrase. In longer paragraphs, their use in every sentence would become repetitive and distracting.

But as you can see in the above examples, it helps when you’re clear about the connections between ideas! Don’t underuse connectives!

A Closer Look at Grouping and Sequencing

The first strategy we explored separated out and grouped together similar ideas. In the case of that example, the pattern was:

- Problems postsecondary students face

- Attempts to address the issue

This sequence is logical.

One thing you might do as a writer is expand on the “problems” section. For instance, you might decide to pay special attention to the problems students face getting jobs. Now you have two parts looking at “problems” and one at “solutions.” You need to decide on the order of the two parts on problems.

One possibility is to go from most important to least important. Another is from least important to most important. (These choices assume one idea is more important than the other. Usually we can rank our ideas like this.)

Let’s say you want to zero in on job prospects as the most serious issue. Here is the topic outline, going from more important to less important:

- The most serious problem facing students today is lack of job prospects.

- Students face a number of other pressures, too.

- There have been attempts to address these issues.

You can reverse 1 and 2, and go from less important to more important:

- Students face many pressures today.

- Of all these, the most serious problem is lack of job prospects.

- There have been attempts to address these issues.

You can also build out each larger topic in more than one paragraph, each with its own topic sentence, or central point.

You’ll often notice that in skillful, cohesive writing, when you extract and join together the first sentence of each paragraph, you get a logical summary of the whole piece.

For example, look at the following breakdown of eight paragraphs in a row from Anthonella Alvarez’s “Barriers in the Classroom.”

Notice the following:

- The ideas fall into three main topics (language barriers, cultural exclusion, positive signs). These are labelled with roman numerals (I, II, and III) and headings. (These roman numerals and headings do not appear in the original.)

- The first sentence of each paragraph (recorded below) is the main idea for that paragraph.

- Paragraph 4 transitions between the first two categories, showing similarity between them.

- Paragraph 8 transitions into the third topic, showing contrast (“However”).

- The ideas flow logically from one to the next. Alvarez has carefully sequenced them. Reading just these opening sentences of each paragraph, you can follow almost the entire argument.

(All quotes from Alvarez, 2020)

I. Language Barriers:

- “One of the most obvious challenges Latinx students have in the classroom is the language barrier.”

- “Because of the language barrier, a lot of Latinx students are assumed to be not as smart as their peers and many teachers give up on them.”

- “Most public schools have English Language Learning programs, yet they are mostly underfunded or understaffed.”

II. Cultural Exclusion:

- “Our challenges do not stop there. Our cultures play a role, too.”

- “The pressure to assimilate and be “normal” when you have an immigrant family or are an immigrant student is a big weight that no one else carries. […]”

- “Educators play a huge role in these struggles.” [Alvarez goes on to describe how educators often fail to include Latinx cultures and multilingualism in the classroom.]

- “This exclusion and erasure of Latinx culture makes staying in school and learning even harder for students who are the first or second generation of their family to receive formal education, at any level.”

III. Positive Signs:

- “However, not all is lost.”

Read the original article to see how these ideas are fleshed out in each paragraph.

A Closer Look at Connection

We saw above how you can use connectives—linking words and phrases—to show relationships between ideas.

There are two more useful techniques called “consistent subjects” and “old-new flow.”

Consistent Subjects

“Consistent subjects” means starting each sentence (or main clause) from the same perspective. For a given chunk of text (a paragraph or other group of sentences), start each main clause on the same subject or its equivalent (e.g. a pronoun). These are sometimes also called “topics.” They are what each sentence is about.

You can picture it like this:

Subject → statement about that subject. Subject → another statement about that same subject. Subject → statement about that same subject.

If you remember, one of the solutions we looked at before involved adding connective words. Well, the first part of that solution also uses this technique of consistent openers:

1 Students face many pressures today. 2 For example, they are greatly in debt. 3 They’re also stretched thin.

Each sentence is about “students.” The word “students” or the equivalent pronoun “they” appears at or near the start of each sentence.

Notice how the consistent subject technique can be combined with the connectives technique (the use of “for example” in sentence 2).

You can see the same technique in one of the paragraphs in Alvarez’s “Barriers in the Classroom,” where “educators” (replaced in most sentences by “they”) is the consistent subject:

“Educators play a huge role in these struggles. As the first line of defence, they should try to create a more inclusive classroom. However, unless a problem is explicitly brought to their attention, they will create lesson plans that exclude anything outside of the “ordinary,” like reading materials that might speak to Latinx cultures, or an understanding of what it’s like to speak multiple languages” (Alvarez, 2020).

Notice that in the second and third sentences, the word “they” starts each main clause but not the sentence itself.

There’s no rule that you can only have one consistent subject. You can probably have two or even more depending on the length of the section or paragraph. Use your judgment. Just be aware that the whole point is that if there are too many subjects, the writing may become unfocused, unless you’re using another technique to make the writing cohesive.

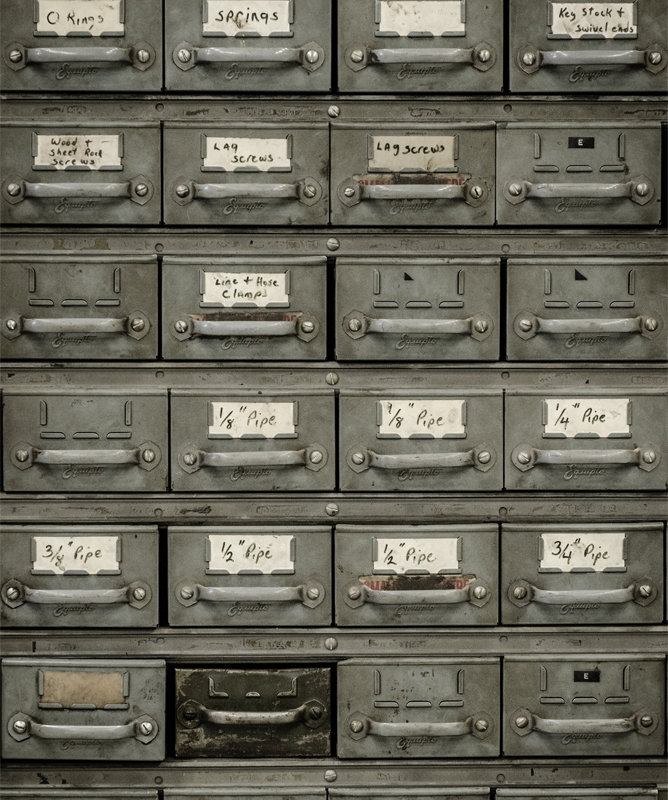

Old-New Flow

Another technique is “old-new flow.”

In your sentences, try to move from old information (what you’ve already told the reader) to new information (the point you are adding).

Repeat this process in an ongoing chain link of ideas.

Typically, each new sentence picks up where the last one left off, although there’s no hard and fast rule about this. It’s just a general pattern.

Old information is information the reader already has, typically because you’ve just given it to them:

This sentence establishes idea A by the end. Idea A is at the start of this sentence, and now we add on idea B. Idea B is signalled here to anchor the reader, and we can safely add idea C…

Let’s rewrite one of the solutions above using this new technique:

Students face many pressures today, from rising debt levels to overwhelm. And these pressures may not be worth it, because students’ postsecondary credentials are no longer enough for employment. In fact, job prospects …

Here’s another, more complex example.

When my ancestors made treaty with the Crown, the original intent and outcome was never based on the idea that we, as Indigenous nations, would assimilate to the point that we would deem our own political and traditional governance systems irrelevant and dissolvable.

With this knowledge, I know that in order to have strong, healthy nations, I must raise my daughter with the knowledge of the original intent and outcome of those treaties. This, in turn, aids in the reminder of the immortality of treaty.

The fact is, treaties are of international stature. (Landry, 2019)

The strategies we’ve looked at can be adapted and combined in various ways. The following passage uses a mix of consistent subjects and old-new flow (see if you can also spot the connectives and use of topic sentences!):

Students face many pressures today, from rising debt levels to overwhelm. They’re taking out loans to pay ever-rising tuition and living costs. Moreover, they find themselves stretched too thin. For example, in one recent survey, 90% of respondents reported feeling overwhelmed by the tasks they had to complete. And these pressures may not be worth it, because students’ postsecondary credentials are no longer enough for employment.

In fact, job prospects are perhaps the most serious issue.

Combined, these techniques create prose that feels coherent and connected. We can see how the various ideas relate, how they build one to the next, and how they’re grouped together.

Try It!

Make your writing flow for your readers, so ideas are connected and easy to follow:

- Group similar ideas together.

- Use topic sentences to identify the main idea of a paragraph or section.

- Use connectives (“also,” “but,” “for example,” “in short,” “more/most importantly,” “moreover,” etc.).

- Use consistent subjects (start your sentences or main clauses on the same noun or small group of nouns within a particular passage).

- Use old-new flow (begin the next sentence on the idea you ended with in the previous one).

References

See Develop Flow References

A group of words that can stand alone as a complete sentence, independent of any other group of words. It has at a minimum a grammatical subject and finite verb.