21 Clarify, Respond, and Infer

Sarah Duffy

Raise questions about a source to clarify its message and context. Make personal connections and respond by drawing on your experience and world knowledge. Reach credible, respectful conclusions about a source’s unspoken meaning.

What You’ll Learn:

- Why clarify and respond personally

- How to clarify and respond personally

- Why infer

- How to infer

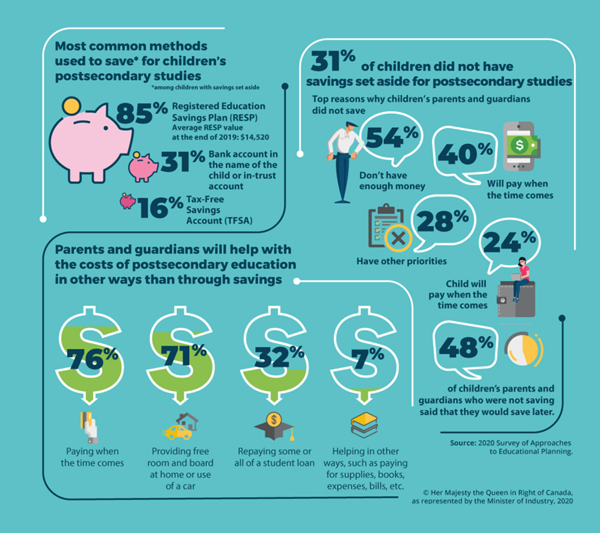

Have a look at this: In September 2020, Statistics Canada published an infographic titled “Saving for Postsecondary Education, 2020.” Check out the full infographic here.

Think about this: Focus on the inserted portion of the infographic. What do you want to know about these numbers? What is unclear? Are there parts of the infographic that you would like to know more about? How does this information relate to your own experience with saving for postsecondary education? Have you learned anything from the infographic?

Why Clarify and Respond

Why Clarify

When engaging actively with a source, you will have questions about its content, its form, its author, its context. These questions reflect your immersion in and connection with the source. Clarifying involves addressing these questions by

drawing on prior experiences;

decoding areas of the source that are confusing;

looking for answers if possible or relevant; and

going beyond what is said by the author.

Why Respond

When you absorb a source, you will have a personal response to it since it will impact you in myriad ways. In some cases, you will share the author’s viewpoint; in others, you will disagree. You may find some ideas surprising, interesting, and persuasive. Conversely, at times, you will be confused, disinterested, or even upset.

Capturing your response is important since it

furthers your engagement with a source;

helps in identifying areas “in common” with the author;

creates conversations; and

can be a starting point for critical evaluation.

How to Clarify and Respond

How to: Clarify

When you clarify, your questions will vary depending on the type of source and your prior knowledge. You might have questions about

- the author’s life experience and background, including what motivated them to share their views;

- the political, social, or cultural environment at the time of writing or publication;

- the conclusions that were drawn by the author(s) and the support provided;

- verifiability of the source with others in the same field or on the same topic; or

- methodology, sampling, and data collection and use (if it’s a journal article or research study).

At this point, you will search quickly to find answers since a more thorough and research-driven evaluation or critique will come later.

How to: Respond Personally

When developing your personal response, a number of questions can guide you:

- Is the content relevant to me as a reader? Does it support or contradict my life experience?

- In what ways do I agree/disagree with the point of view, the argument, the conclusions?

- Am I persuaded by the content?

- What challenged me? What have I learned? How have my views changed as a result of reading this material?

- What do I want to know more about?

There are no right or wrong answers. However, your response should be respectful and considerate, informed by reflection on your connection to the content and an open-minded absorption of the source.

You’re reading an analysis report from Statistics Canada titled “Inequality in the Feasibility of Working from Home During and After COVID-19.” It highlights imbalances that exist in the ability to work from home, an important and recommended containment strategy during the COVID-19 global pandemic.

Clarify

As you read this report carefully, you might have several questions about areas of the report that are unclear or seem limited in some way. These may include the following:

| Question | Specific Example |

|---|---|

| What is the method of data collection that was used? Where does the data come from? How can I learn more about the data? | The Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey 2019 is cited as the source of data for chart 1. Could I learn more by looking at this survey? |

| Are there any flaws in how the study was conducted? In its use or explanation of terms? | For example, when discussing households (see chart 1), why are “husbands” and “wives” used when discussing dual income families? Why isn’t the more inclusive term “partners” used? |

| Who was included in the study? Who was excluded? | If participation was voluntary, who chose not to participate? Were Canadians from across all provinces and territories sampled? |

| Does the evidence support the conclusions? Are there weaknesses? | What does table 1 show? Is it based only on “primary income earners” per its title, and if so, how does this impact the conclusions? |

| How do this study’s findings compare with others on the same topic? Do they make the same or a related argument? What are the areas of disagreement? | How do the conclusions compare to these other articles on related topics? “Coronavirus Highlights the Inequality of Who Can — and Can’t — Work from Home” by Abigail Hess (read it here) “Working from home reveals another fault line in America’s racial and educational divide” by Christian Davenport, Aaron Gregg and Craig Timberg (read it here) |

Respond

Your personal response to this report will be unique and will reflect your experiences. Here is a sample personal response:

The findings relate to me since I have been able to work from home during the pandemic, a situation I have appreciated. While I would like to clarify some of the data and the authors’ interpretation of it, I can see, based on observing life around me during the pandemic, that these inequalities are apparent. The choice to “stay home” during the pandemic was not possible for many. I am challenged to uncover what can be done to address this type of inequality and to learn more about other inequalities uncovered or driven by the pandemic.

Why Infer

You have absorbed the author’s voice and perspective respectfully. Now, you’re ready to move on and make inferences.

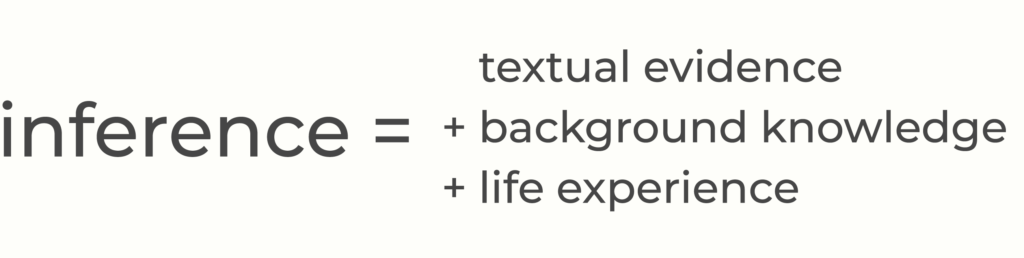

When you make an inference, you connect further with the author’s message, draw conclusions, and read “between the lines.” You use knowledge of the world and your previous experience. You’re looking at what is written or said—the evidence—to form opinions about what is not.

When you infer, there is no right or wrong answer, but any inference should be supported with logic and evidence. Others’ inferences should be accepted and respected even if they differ from the conclusions you have drawn about the same source.

All About Schema

Did you know that when you apply your background knowledge and life experience to absorb a source, you are using your internal cognitive frameworks known as schema (plural = schemata)?

In a 2015 study, “An Empirical Study of Schema Theory and Its Role in Reading Comprehension,” the term is explained: “Schema can be defined as the abstract knowledge structure the reader brings to the text” (Liu, 2015, p. 1349).

We all have our own internal schema, developed and molded by our life experience. No two schema will be the same. Schema are important for comprehension of sources. According to the same author, “meaning does not have a separate, independent existence from the reader, and prior knowledge of the reader or schema counts a lot in the extraction of meaning from the graphic words” (Liu, 2015, p. 1349).

Inference or Prediction?

Inferences and predictions are closely related but different.

Predictions are statements about the future that can be explicitly confirmed at some point. For example, if you predict at the start of a course that you will get an A grade, once the final grades are shared by the professor, the prediction will be verified as either correct or incorrect.

Inferences, however, cannot be explicitly confirmed. They are reasonable conclusions based on evidence, knowledge, and logical reasoning. For example, if you got a D grade in an online course but are typically a B-grade student in face-to-face courses, you may conclude that the online learning environment does not work for you. You would be using your knowledge (of yourself as a student) and the evidence (your grades) to draw this conclusion. However, other conclusions could be logically drawn too, including that your grade in the online course was influenced by poor course design, limited teacher interaction, and less peer collaboration.

How to Infer

To infer effectively, you should

- understand background and context (see Situate);

- use your knowledge of the author and the rhetorical situation (see Situate);

- look for clues and keywords (see Skim, Scan, and Use Tools);

- consider the “how” and “why” related to the “what”;

- use facts, details, and evidence (see Break Down a Source);

- use your prior knowledge and personal experience;

- develop an informed opinion; and

- check and double check your logic.

When you infer, you can draw conclusions in a number of ways:

(Adapted from “Infer with Evidence” by Barbara Radner. http://teacher.depaul.edu. Used with permission.)

| Infer motive | Why does the author believe this? What did the author want you to feel or understand? |

| Infer prior actions or experiences | What life experiences influenced the author? |

| Infer cause-effect | What caused _______ to happen? |

| Infer traits | What can you conclude about a person’s personality or values? |

| Infer beliefs and values | What does the person believe or value? |

| Infer feelings | How do you think ________ felt about a subject, person, life, situation, etc.? |

| Infer the main message | What is the main message that the author is sharing? |

When making inferences, you should track, support, validate, and iterate your thinking. These questions can help:

- What is my inference? (capture the conclusion you are drawing)

- What information did I use to make this inference? (capture the textual evidence and, when possible, the background knowledge and life experience)

- How valid is my inference? Do I need to change my thinking? (reflect on your logic)

You read the following passage about the use of TikTok:

I stare at the screen. It’s foreign to me, but I’m intrigued, entertained, sometimes inspired. Hearts and plus signs, arrows and comment boxes. Short dance routines. Lip-syncing memes. Strangers sharing life beliefs, life hacks, life stories. Should I watch? Should I swipe up? Should I follow or share or favourite? A tourist on TikTok, passing pandemic-restricted time. Thirty seconds becomes 30 minutes. Just one more video. Hours spent during lockdown.

You think about the inference(s) you can make from this passage, carefully considering what evidence is available. You consider these inferences:

- The author is a millennial.

- The author is a new user of TikTok.

- The author does not like life hacks.

- The author believes that it is easy to pass a lot of time on TikTok.

You decide that (b) and (d) are inferences that can be made logically from this passage; (a) and (c) are not.

(b) is an inference since the author’s use of the terms “foreign land” and “tourist” indicate that they are new to TikTok. This is also indicated by the author’s confusion about TikTok’s functions—e.g. “How do I share again?” Further, the author indicates that their use of TikTok may be related to the global pandemic when stating “pandemic-restricted time” and “hours spent during lockdown.”

(d) is also an inference since the author ends the passage by talking about time passing while using TikTok—e.g. “Thirty seconds becomes 30 minutes”; “hours spent.”

Although (a) is possible since millennials are not the typical users of TikTok, the author could also be older, part of Generation X or the boomer generation. There is no evidence to indicate that the author does not like life hacks. Therefore, (c) is not a logical inference.

Try It!

Activity 1

Directions

- Watch “Why It’s Time for Black History Month to Go” by Bee Quammie, a Canadian freelance writer. In this piece, Quammie expresses her thoughts about the limitations of celebrating Black Canadians just one month of the year.

- After watching the video, clarify Quammie’s message by identifying questions you have about it. Then, respond to Quammie’s message. Compare your clarifying questions and response to the sample provided, but remember there are no right or wrong ways to clarify or respond.

Directions:

- Watch “What Non-Indigenous Canadians Need to Know” by Eddy Robinson, an Indigenous speaker, consultant, educator, and author. In this video, part of TVO’s web series called “First Things First,” Robinson provides advice to non-Indigenous Canadians.

- After watching the video, clarify Robinson’s message by identifying questions you have about it. Then, respond to Robinson’s message. Compare both with a peer, but remember there are no right or wrong ways to clarify or respond.

Activity 3

Directions:

- Review the following four passages. For each, answer which of the four statements that follow are inferences. Can you support your answer with logic and evidence?

- Check your answers with the solutions provided.

1. “It’s not that digital immigrants are smarter or more talented than the digital natives that came after us. Our uniqueness, it seems, lies in the fact that we are the last of a dying breed and as such, living, breathing receptacles of a soon-to-be lost plane of human experience: empty yawning hours and days of nothing much at all” (McLaren, 2019, para. 11).

What inference(s) can you make from this passage?

- The author is a digital native.

- The author believes that digital immigrants are unique.

- The author thinks that the human experience has been changed by technology.

- The author does not like technology.

solution

2. “So if you’re a person that wants to be an ally to the Black community, let’s begin here: Put down your phone. Just as neutrality won’t put you in good stead with the cause of righteousness, neither will claims that you’re ‘not racist.’ The notion is a myth; certainly 400-plus years of deeply ingrained social programming didn’t simply skip over you, regardless of your good intentions. Racism lives within all of us. Your active allyship work begins with letting this realization sink in, and then taking steps towards becoming anti-racist” (Fequiere, 2020, para. 3–4).

What inferences can you make from this passage?

- The author thinks that being a Black ally is not just about posting on social media.

- The author believes that people want to be an ally to the Black community.

- The author believes that becoming a Black ally begins with acknowledging your own racism.

- The author believes that allies must take proactive and concrete action.

solution

3. “Police use-of-force incidents across Canada have ignited public unrest and disapproval of law enforcement authorities. Many voices are calling for the widespread use of body-worn cameras to hold police officers accountable, while others are urging government to defund the police. An area that has not received the attention it deserves during this upheaval is police oversight” (Laming, 2020, para. 1–2).

What inferences can you make from this passage?

- The author thinks that police should be defunded.

- The author believes there should be focus on police oversight.

- The author believes that police oversight in Canada should be examined.

- This piece was written at a time of societal turmoil.

solution

4. “Anyone who represents a ‘different’ point of view also needs to accept that questions may not be wrapped in a perfectly politically correct bow. That doesn’t mean we should stop the questions from being asked. We need to keep conversations going; I would much rather someone stumble over their words or offend me or not know the HRC-approved way to ask me which pronoun I prefer than stay silent. Silence halts change” (Beckham, 2014, para. 3).

What inference(s) can you make from this passage?

- The author has been asked politically incorrect questions.

- The author believes that dialogue between people of different backgrounds and identities is necessary for societal change.

- The author wants to keep conversations going.

- The author does not like questions.

solution

In this subtopic, you learned that

- paraphrasing is different from summarizing but has many similarities;

- a paraphrase should use distinct words and sentence order/structure;

- synonyms do not exist for all words; and

- a paraphrase is considered plagiarism if it is not correctly cited.