1

I’d like to start out by quoting a former student who wrote the following after having taken the course “Cultures of Entrepreneurialism”:

I took an Introduction to Entrepreneurship class last year that had a very formal, and strict definition. The class textbook defined entrepreneurship as, “the process by which individuals pursue opportunities of exploiting future goods and services” (Barringer & Ireland, 2019). It had very straight-forward answers as to why individuals may become entrepreneurs, including in order to be their own boss, pursue their own ideas, or pursue financial rewards (Barringer & Ireland, 2019). In addition, it listed four characteristics that all entrepreneurs have, being a passion for the business, product / customer focus, tenacity despite failure, and execution intelligence (Barringer & Ireland, 2019). This information is what shaped my understanding of entrepreneurship, until I took this course, which taught me that entrepreneurship is not necessarily a strict rulebook for one to follow. [1]

That’s good, but it doesn’t tell you what the course is, only what it isn’t (it isn’t something that boils down to a simple definition or even a simple object of attention).

I had another student report that this course was a like a philosophy of business course, and I thought that summed it up kind-of nicely. Except that the figure of the entrepreneur is so omnipresent in today’s media and business culture that it might be more accurate to suggest that this course examines entrepreneurship as a philosophy of life (and what that means, both positively and negatively, for those who are subject to it). And here’s a big hint – we’re all subject to it! The course is not an examination of entrepreneurs, as they are traditionally understood. It is an examination of entrepreneurship. And it doesn’t presume that there is just one culture that describes and prescribes what it means to be an entrepreneur. Rather, there are multiple cultures of entrepreneurship (note the emphasis on the plural in the course title!). There are also lots of distinct types of entrepreneurs! And, perhaps most importantly, we also start out with the notion that we are all asked to be entrepreneurial. What does this mean?

Imagine you have been presented with a multiple-choice test with the following question:

Which one of the following is an entrepreneur?

(a) Richard Branson

(b) Terry Fox

(c) a drug dealer

(d) a panhandler

(e) all of the above

(f) none of the above

Now, your first inclination might be to pick (a) since Richard Branson, the founder of Virgin Records and Virgin Airlines, is a well-known entrepreneur. But if you’re smart, you read through all the choices anyway, and if you’ve written a lot of multiple-choice tests, you probably think (e) could be a legitimate option too — many times “all of the above” is given as a choice when more than one answer is correct. But though Terry Fox successfully raised a lot of money, he certainly wasn’t a business person. And a drug dealer “might” be considered a “business person.” But since the business is not socially sanctioned and illegal, they usually aren’t invited to give inspirational speeches or write autobiographies based on their life journey. And panhandlers, or urban beggars asking those who pass by for donations, aren’t running a business and are in many cases just trying to get through another day; they are not introducing a new product to market or offering a life-altering service or selling anything, even a dream. Presumably, when we consider the choices, “all of the above” doesn’t inherently make sense. But “none of the above” clearly doesn’t work either; we know Richard Branson as a successful businessman whose public image is based upon being a rule-breaking, uber-profitable entrepreneur. This last option must be a canard, just like “all of the above”, meant to confuse us.

But the answer is indeed (e) — all of the above ARE entrepreneurs (or can, at least, be viewed as such). In fact, you probably are also an entrepreneur (or at least have acted entrepreneurially at some point in your life) . How can this be?

Let us start somewhere obvious. The figure of the entrepreneur is typically presented as someone who is either starting up or running their own business. This dominant meaning is so widespread that non-academic books by entrepreneurs (typically successful business people) or for entrepreneurs typically don’t even bother to define the term. Take, for instance,

Power’s book is designed for the emerging businessperson, immediately addressing readers as entrepreneurs who want to “lead better, think better, work differently and more focused, and ultimately find the success you want” (ix). It dispenses advice to “seize opportunity and never stop growing. Think of your business like a well-trained muscle” (x). It never precisely outlines what it means to be an entrepreneur but does offer the following observation: “When you get a job, your employer has a job description that describes what you need to do. When you become an entrepreneur, however, you have to decide for yourself the person you want to be” (23). The Entrepreneur’s Book of Actions coaches readers, therefore, in the art of “entrepreneurial engagement [which] is held up as a way to both gain an income and give one’s life meaning.” [2]

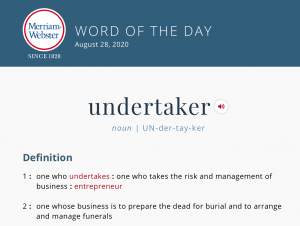

The historical origins of the term “entrepreneur” connect it to both the economy and to the idea of risk. Cantillon, writing in the early 18th century, viewed an entrepreneur as “someone who buys at a certain cost price and sells at an uncertain price.”[3] According to Cantillon, “there were three main sorts of economic actors: there were the landlords who owned the land; there were the labourers who worked, often for the landowners, for a wage; and there were the entrepreneurs [with] … uncertain income because it depended on factors beyond their control.” [4] Indeed, “the word “entrepreneur” originates from the French word entrependre, which means “undertaker” as in the sense of someone undertaking a major project.” [5]

We can understand the entrepreneur, then, as not just someone who undertakes risk to build an enterprise, but as anyone who undertakes a task or is enterprising. “To be entrepreneurial or enterprising means utilising opportunities and changes and having the ability to carry out activities aimed at improving, developing and creating values that may be social, personal, cultural or economic” [6] While “profit-making exchange, personal risk, opportunity, newness, and added value are explicit or implied in most researchers’ conceptions of entrepreneur and entrepreneurship,” [7] “the goal of entrepreneurship is not always profit. …The entrepreneur always searches for change, responds to it, and exploits it as an opportunity.” [8] Beyond the business world,

[Entrepreneurship] involves the application of human creativity, ingenuity, knowledge, skills, and energy to development of something new, useful, and better than what currently exists—and that creates some kind of value (social or economic). … In fact, individuals can think and act entrepreneurially without necessarily launching a new venture. What is essential is simply that they take action to move their ideas from the possible to the real.[9]

Today, it might seem that entrepreneurship and the figure of the entrepreneur increasingly define all human activity. Indeed, anyone can add #entrepreneur to their instagram post in an effort to turn their ideas into reality (and their reality into $$).

These varieties of self-promotion provide further evidence that the concept of the entrepreneur is a slippery one. Some point out the entrepreneurial nature of the beggar to argue that “entrepreneurship today can be almost anything,” and ask “who cannot lay claim to being an entrepreneur?”[10] It is an empty concept, taking on an endless variety of shapes as it operates in different discourses and adjusts to fit in with different social contexts. This fluidity of meaning and its seemingly endless malleability present a conceptual challenge and, pun intended, an opportunity: “The function of the entrepreneur as an empty signifier … has been of considerable importance for understanding its apparently perennial attraction; as an ‘empty’ signifier it can be (almost) whatever one desires it to be.”[11]

If the entrepreneur can be almost anything and almost anybody can be an entrepreneur, maybe one ought not to try and pin down any definitive definition of an entrepreneur. This quest seems to be destined to be ever frustrated. After all, nearly 50 years ago, one author “likened the search for the source of entrepreneurship to hunting the ‘Heffalump’: the much sought after, but never quite found, animal in Winnie-the-Pooh.”[12]

This is an instructive analogy but it only goes so far. In the original A.A. Milne story “In which Piglet meets a Heffalump”, we encounter the following exchange:

This is an instructive analogy but it only goes so far. In the original A.A. Milne story “In which Piglet meets a Heffalump”, we encounter the following exchange:

“I saw one once,” said Piglet. “At least, I think I did,” he said. “Only perhaps it wasn’t.””So did I,” said Pooh, wondering what a Heffalump was like. “You don’t often see them,” said Christopher Robin carelessly. “Not now,” said Piglet. “Not at this time of the year,” said Pooh.

Heffalumps may or may not exist and in any event they are awfully difficult to apprehend. They may even be imaginary. However, entrepreneurs seem to be everywhere, always clamouring for our attention. Though not a product of our imaginations, “Entrepreneurship has come to permeate our social imaginaries in a way that has quickly transformed its claims and demands on us from fantasy into reality.”[13] We hail them as heroes, we are inspired by their successes, and sometimes whole economies are buoyed by their innovations. Yet in a way, “entrepreneurship is like obscenity: nobody agrees what it is, but we all know it when we see it” [14] The struggle to pin down any particular meanings is likely to be ever unresolved. But the centrality of the entrepreneur is arguably never greater. Thus, it behooves us to look, instead, to particular social settings and particular forms of entrepreneurial expression and struggle in order to attempt to shed further light on what “entrepreneur” might mean and establish why it matters.

- see Barringer, R. B. & Ireland, D. R. (2019). Entrepreneurship: Successfully launching new ventures (6th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson Education. ↵

- Imre Szeman (2015) “Entrepreneurship as the New Common Sense.” The South Atlantic Quarterly, 114(3), p.474 ↵

- Sander Wennekers and André van Stel (2017) "Types and Roles of Productive Entrepreneurship: A Conceptual Study." In The Wiley handbook of entrepreneurship, Gorkan Ahmetoglu et al. (Eds.) Hoboken, NJ : John Wiley & Sons, p. 45. ↵

- Simon Bridge (2017) The Search for Entrepreneurship: Finding More Questions Than Answers. London: Routledge, p. 23 ↵

- Lisa Bosman and Stephanie Fernhaber (2018) Teaching the Entrepreneurial Mindset to Engineers. New York: Springer, p. 9 ↵

- Eva Leffler and Gudrun Svedberg (2005) “Enterprise Learning: a challenge to education?” European Educational Research Journal, 4(3), p.221 ↵

- J. Robert Baum, Michael Frese, Robert A. Baron, and Jerome A. Katz (2007) “Entrepreneurship as an area of Psychology Study: An Introduction.” In The Psychology of Entrepreneurship, J. Robert Baum, Michael Frese, Robert A. Baron (Eds.), New York: Psychology Press, p.6. ↵

- Lisa Bosman and Stephanie Fernhaber (2018) Teaching the Entrepreneurial Mindset to Engineers. New York: Springer, p. 10 ↵

- Robert A. Baron (2012) Entrepreneurship, an evidence-based guide. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, p. 4 ↵

- Campbell Jones and Andre Spicer (2009) Unmasking the entrepreneur. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, p. 2 & p. 9 ↵

- Kate Kenny and Stacey Scriver (2012) "Dangerously empty? Hegemony and the construction of the Irish entrepreneur." Organization 19(5), p. 617 ↵

- Simon Bridge (2017) The Search for Entrepreneurship: Finding More Questions Than Answers. London: Routledge, p. 70 ↵

- Imre Szeman (2015) “Entrepreneurship as the New Common Sense.” The South Atlantic Quarterly, 114(3), p.472 ↵

- K.G. Shaver and L.R. Scott (1991). "Person, process, choice: The psychology of new venture creation." Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(2), p. 24. ↵

Feedback/Errata